Macroeconomic Issues That Confront Our Future

Macroeconomic theory developed over the last 200 years, especially during the 80 years after Keynes. Until recently, economists thought they had the understanding and the tools to make depressions or deep recessions a thing of the past. For the last 30 years, a general consensus grew among economists that monetary policy should handle most of the task of keeping the economy on a steady low-inflation growth path. The recent financial crisis and subsequent recession has made the profession question that conclusion. This downturn has reinvigorated those who felt that fiscal policy should have more of a role, as well as those who felt that government should have a smaller role overall.

This section uses the theories and tools we have learned to understand the important issues that confront our economy today and will do so in the future. Specifically, what are the pressing macroeconomic issues that will have the greatest effect on the next generation? What do macroeconomic theories tell us that policymakers can do?

If you take one idea away from this course it should be that there is not one economic model or one economic policy that fits all occasions or circumstances. It often seems that one set of policymakers see “cutting taxes” as the universal cure-all while others see “more government spending” as the only solution. Both are wrong. Different circumstances call for different approaches.

In the following, we set out the key points surrounding three important issues facing our economy today and likely in the future: (1) the existence of jobless recoveries and persistent unemployment, (2) growing debt and the threat of long-run inflation, and (3) the importance of achieving economic growth in a globalized economy. Throughout this book, we have presented different models and the circumstances in which macroeconomic policy can be effective in these situations.

Are Recoveries Becoming “Jobless Recoveries”?

Globalization, new technologies, and improved business methods are making the jobs of policymakers much more difficult and may even be changing the nature of the business cycle. The 1990–1991, 2001, and 2007–2009 recessions all deviated significantly from what has happened in past business cycles in that they were followed by jobless recoveries.

Taming the business cycle has proven to be just as much of an art as a science. Whenever economists believe they have finally gotten a handle on controlling the economy, some new event or transformation of the economy has taken place, humbling the profession. There is no doubt that between 1983 and 2007, the federal government and the Fed did a remarkable job of keeping the economy on a steady upward growth path, with only two minor recessions. The 1990–1991 and 2001 recessions were mild, but the recoveries coming out of these recessions were weak, especially for those out of work and looking for a job.

jobless recovery A phenomenon that takes place after a recession, when output begins to rise, but employment growth does not.

Recall what we described as a jobless recovery in an early chapter of this book. When output begins to grow after a trough, employment usually starts to grow. But when output begins to rise yet employment growth does not resume, the recovery is called a jobless recovery.

359

We have already seen that business cycles vary dramatically in their depth and duration. The Great Depression was the worst downturn in American history, while the 2001 recession was one of the mildest. During that recession, the unemployment rate never rose above 6% and real output (GDP) fell only one-quarter of 1% throughout the downturn. But if the recession was mild, the recovery was not as strong as in typical business cycles.

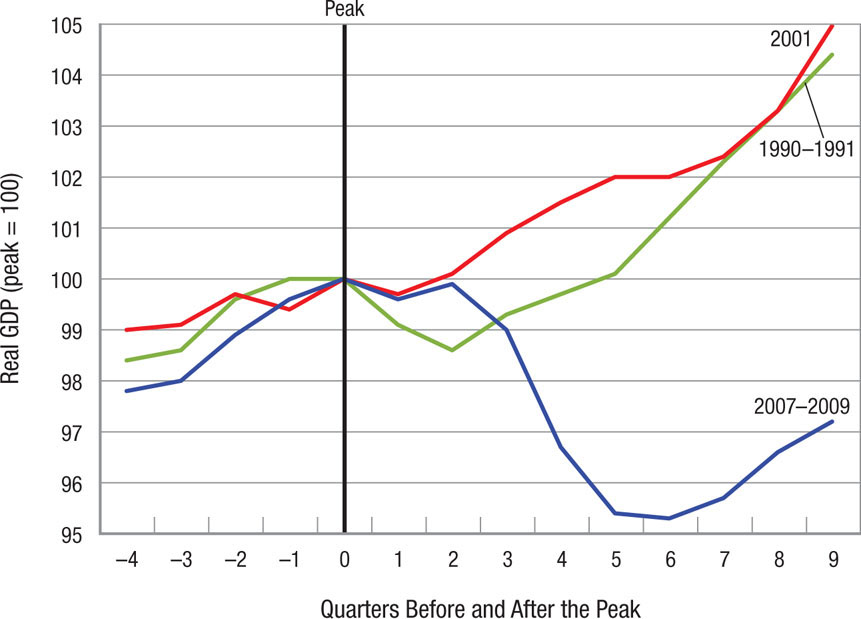

Figure 9 shows how the 2007–2009 recession compares to the two previous downturns and their recoveries. It indexes real output for all three downturns so that the most recent recession and recovery can be compared to those previous business cycles. Specifically, real GDP for each business cycle is indexed to the peak of the cycle. This involves dividing each quarter’s output by output at the peak and multiplying by 100 to index the values to 100. Thus, if one quarter after the peak, output has fallen by 1%, the index would be 99 at that point. In this way we can get a graphical picture of how output is doing throughout the course of each cycle.

Notice in this figure that both the 1990–1991 and 2001 recessions lasted just under three quarters (eight months each). For the 1990–1991 recession, this is shown by the two-quarter drop in real GDP to a little below 99, then the economy resumed an upward path. The 2001 downturn shows a slight dip in the first quarter, but then quickly rises back above 100. Clearly, both of these recessions were mild indeed.

In contrast, the 2007–2009 recession was considerably more severe than both of the previous downturns. A year and a half into this recession, real output fell by over 4% and the decline in the economy was just leveling off.

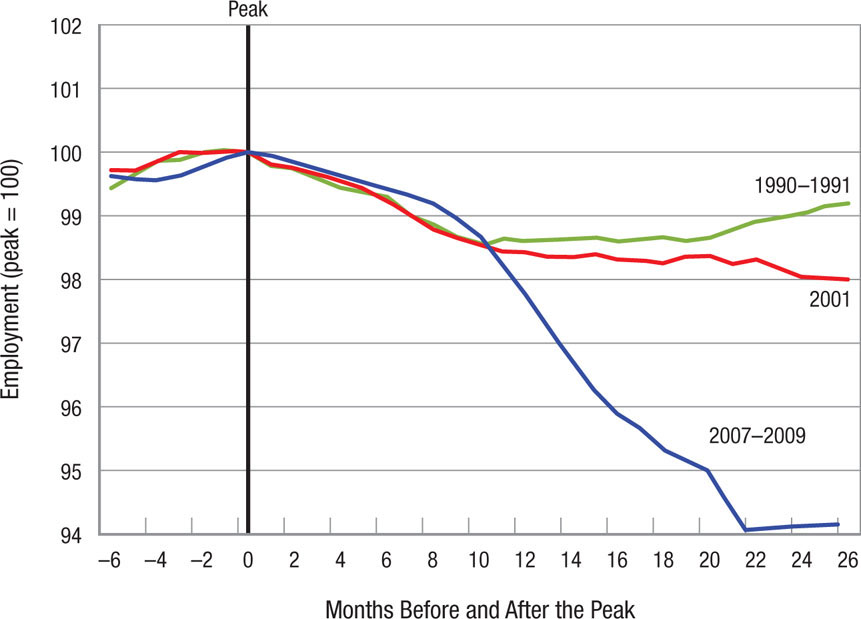

Figure 10 below presents the same type of indexed graph for employment, though indexing the values monthly. Notice that for the 1990–1991 and 2001 recessions, employment had not reached its prior peak even after two years. In fact, employment took nearly three years to return to peak levels after the 1990–1991 recession, and nearly four years after the 2001 recession. In the past, the turnaround in employment to the previous peak was typically reached in two years. Likewise, after the 2007–2009 recession ended in June 2009, unemployment still remained above 7% four years later in mid-2013.

360

Several factors seem to drive jobless recoveries: rapid increases in productivity, a change in employment patterns, and offshoring. Productivity increases arising from improved telecommunications and online technologies make labor far more flexible than ever before. Now when the economy contracts, employers can more easily lay off workers and shift their responsibilities to the workers who remain. As a result, output may keep growing, or at least not drop much, even though fewer workers are employed. When the market rebounds, increased productivity permits firms to adjust to their rising orders without immediately hiring more people. This gives the firm more time to evaluate the recovery to ensure that hiring permanent employees is appropriate. This is why unemployment often keeps increasing even though the economy is recovering.

In addition, hiring practices have changed over the past few decades. Firms have begun substituting just-in-time hiring practices for long-term permanent employees. This includes using more temporary and part-time workers, and adding overtime shifts for permanent employees. By using temporary and part-time workers, and overtime, a firm can increase its flexibility while limiting the higher costs associated with hiring permanent employees until it has had time to evaluate the recovery and the demand for its products.

Because the current and past two recoveries have been slow to add jobs, economists and policymakers are concerned that jobless recoveries have become the norm following recessions. The consequence of jobless recoveries is that reducing unemployment requires much more government action than before, especially expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. What type of fiscal and monetary policies can be used to address jobless recoveries?

Expansionary fiscal policy is most effective when government spending or tax cuts generate economic activity through the spending multiplier, which translates into jobs being created. Alternatively, fiscal policy can be used to provide incentives for employers to hire workers (such as tax incentives for hiring veterans) or employee incentives (such as increased tax deductions for low-income workers).

Alternatively, expansionary monetary policy can be used to promote employment. For example, increasing the money supply and lowering interest rates reduce the cost of financing major projects, creating jobs. The Fed’s recent quantitative easing programs that bought up risky mortgage-backed assets reduced long-term interest rates, creating another boost to consumption and investment.

361

Although plenty of policy options exist to address jobless recoveries, they do not come without costs. For example, a reduction in consumer or business confidence can reduce the willingness of consumers and firms to spend, diminishing the multiplier. Increased government spending can lead to greater debt and higher interest rates, which can crowd out private consumption and investment. Therefore, the intended effects of fiscal policy are mitigated. Further, increased money supply and quantitative easing programs can lead to inflation in the long run, as more money chases an economy’s output. Such effects can mitigate the long-term benefits of monetary policy.

In sum, the potential consequences of using expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to reduce the unemployment rate are higher debt and potential inflation, important issues to which we turn next.

Will Rising Debt and Future Debt Obligations Lead to Inflation?

Much of the debate among policymakers in recent years has centered on rising deficits and national debt. Indeed, fiscal deficits and national debt (at least in nominal terms) have risen to levels not seen in our history. The concern over debt has changed the politics in Washington, as a bitter debate ensued regarding the use of expansionary policies (such as stimulus spending and quantitative easing) to promote economic growth versus austerity measures (cost cutting) to reduce the deficit and the burden of the debt on future generations.

Rising Future Debt Obligations: Health Care and Social Security Even if the current deficits are brought under control using a combination of government spending cuts and tax increases, the long-term debt obligations relating to Social Security payments and rising health care costs pose a bigger question about the ability to keep deficits and debt under control over the long term.

As greater numbers of baby boomers (those born soon after the end of World War II) retire, more will begin receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits. In addition to greater numbers of beneficiaries, the cost of the benefits also rises. Social Security benefits increase based on the rate of inflation, while Medicare payments rise as the cost of health care increases.

Although recent legislation has slowed the rise in health care costs, the overall cost remains unsustainable in the long term. In addition, the long-term debt obligations stemming from health care and Social Security do not fully appear in current deficit statistics, because these expenses are budgeted and paid out during the year in which the costs are incurred. Therefore, if costs rise faster than revenues, deficits will persist, adding to the national debt.

The Cost of Financing Debt The cost of financing debt depends on the interest rate. Fortunately, the United States has enjoyed very low interest rates for much of the past decade. This not only helps individuals and firms looking to borrow, but also the government in financing its debt. A new 30-year Treasury bond issued in 2013 paid only about 3% per year. In 1984, a new 30-year Treasury bond paid over 13% per year. A difference of 10% in the interest rate represents a tremendous savings to the government.

Another factor in the cost of financing debt is the willingness of countries to hold U.S. debt. Part of this depends on the demand for the U.S. dollar. The U.S. dollar remains the most widely held currency in the world. When U.S. dollars are held by foreigners, this amounts to an interest-free loan to the U.S. government, because no interest is paid on currency. The willingness of people around the world to use and hold dollars allows the government to print these dollars without the immediate worry of inflation.

362

The Effects of Debt on Inflation Addressing debt can be undertaken with fiscal policy as well as monetary policy. Fiscal policy to curb debt includes raising taxes or reducing government spending. However, neither of these policies is popular, especially the reduction of Social Security or health care benefits that make up over 40% of government spending. Further, contractionary fiscal policy can curtail economic growth, which is especially dangerous when recovering from a severe recession like the one from 2007–2009. For this reason, policymakers have turned to monetary policy.

monetized debt Occurs when debt is reduced by increasing the money supply, thereby making each dollar less valuable through inflation.

One of the dangers of using monetary policy to help address deficit and debt issues occurs with monetized debt, which is debt that is paid for by an increase in the money supply. In other words, debt is reduced by way of a lower real value of the dollar. Because U.S. Treasury securities have long been sought after as a safe investment by individuals, firms, as well as governments around the world, the U.S. government has not had to worry about the inflationary effects of its monetary policy in recent years.

Inflating Our Way Out of Debt: Is This an Effective Approach?

In late 2012, the news media posted headlines about the possibility of the Fed authorizing the minting of a trillion dollar coin that would be used to pay for most of the year’s fiscal deficit. By doing so, the minted coin would be sent to the U.S. Treasury to pay down the debt. Would such a strategy really work? Would there be any effects on the economy or on ordinary Americans?

Although this type of policy is highly unlikely to occur (though more than one prominent economist has endorsed the plan), what may surprise you is that the Fed has used similar types of policies for years to address our rising national debt.

When the money supply is increased, the Fed is using money that is created out of thin air to purchase treasury bonds (debt) from banks and other institutions. In other words, part of the government’s debt is held by other parts of the government using money it creates through its power to print money. Does this sound like an easy solution?

Certainly, it’s easier than implementing fiscal policies to combat debt, which would require the raising of taxes or the reduction of government spending, neither of which is popular, especially when much of government spending is used for our national defense or to take care of our senior citizens. Therefore, the government has relied more on monetary policy. When money is created to purchase debt instruments, this is referred to as monetizing debt.

As we studied in an earlier chapter, money is neutral. When more money chases a fixed output, prices must rise. Because aggregate demand was depressed after the last recession, inflation did not immediately rise. However, as consumer and business confidence improve, all of the money sitting on the sidelines will eventually enter into the economy and drive prices higher, leading to inflation. As inflation rises, the real value of the national debt falls.

Who, then, ends up paying for this reduction in debt caused by inflation? The answer is everyone who holds dollar-denominated assets, such as those with a savings or retirement account, or holders of bonds including foreign investors and governments. When prices rise, the real value of savings falls. In addition, a rise in inflationary expectations causes banks to raise interest rates, and can lead to an inflation spiral described in the chapter, resulting in even higher prices. In sum, the costs of financing debt by way of inflation are spread among everyone. Regardless of whether fiscal or monetary policy is used, we will all feel the effect of the debt in one way or another.

However, should world demand for U.S. Treasury securities fall as countries diversify their holdings to other assets (such as euro-denominated assets or gold-backed assets), the value of the U.S. dollar may fall. Because we purchase many goods and services from other countries, a weaker dollar increases the prices of many goods and services, leading to inflation. Therefore, although a weaker dollar and inflation both reduce the burden on the existing debt, a higher rate of inflation reduces the purchasing power of one’s income and savings, thereby reducing the standard of living.

363

In order to stem the effects of higher inflation, contractionary monetary policy is needed once the economy has recovered enough to withstand an increase in interest rates. Such policies are not popular. In 2013, the fear of the Fed ending its quantitative easing polices scared many investors who worried about the start of another recession. Still, controlling inflation is the key to preventing more serious problems for the economy. Ultimately, a higher inflation rate may hinder productivity and economic growth, which is increasingly important in a globalized economy.

Will Globalization Lead to Increased Obstacles to Economic Growth?

Economic growth has been the driving force in improving our standard of living. However, the world is changing, and countries that historically have not experienced high rates of economic growth have begun to flourish. Countries such as China, India, Russia, and Brazil have surpassed the growth rates of the United States, Japan, and the countries of Europe over the last decade. Further, smaller developing countries, such as Gabon, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, have seen stellar growth rates that have pulled millions out of poverty.

Why has economic growth spread throughout the world in this way, and what does this entail for developed nations such as the United States?

One of the most important changes to the world economy over the past generation has been the dramatic increase in international trade, international factor movements (foreign investment and immigration), offshoring (the movement of factories overseas), and international banking. The integration of the world’s economies has allowed more countries to specialize and reap the gains from trade that result.

For developed countries such as the United States, Japan, and countries in Europe, increased globalization means increased competition for resources, especially talented labor, which now has many more opportunities than it did in the past. Therefore, pressures to innovate and to increase productivity have increased with globalization.

What does this mean for macroeconomic policy? Not only does fiscal and monetary policy need to be tailored to fit the problems inherent in our own country, but how these policies affect other countries becomes important as well.

Fiscal policies such as implementing trade restrictions or providing support for domestic industries tend to help one country at the expense of its trading partners. Taking these policies too far may encourage other countries to take similar actions, which would lead to fewer exports and a reduction in trade and economic growth.

Monetary policies also affect other nations through trade and the exchange rate. Expansionary monetary policy, such as reducing the interest rate, has the effect of lowering the value of one currency against others. When this occurs, the price of imports rises and the price of exports falls, helping to improve the trade balance as consumers react by purchasing more domestically produced goods than foreign-made goods. But again, such policies can lead to retaliatory actions if taken too far.

We turn our attention in the next two chapters to international trade and open economy macroeconomics. Both chapters deal with how countries interact with other countries, either through the trade of goods and services or through the exchange of currencies. Both have important implications for the ability of countries to grow and to improve their standards of living.

364

MACROECONOMIC ISSUES THAT CONFRONT OUR FUTURE

- No single macroeconomic model can solve all economic problems.

- Jobless recoveries are spurred by increases in labor productivity, changes in employment patterns, and increased use of offshoring. Fiscal and monetary policies provide incentives to consume and invest, leading to job growth.

- Rising deficits were caused by expansionary fiscal policies used to stem the effects of the financial crisis. Future concerns of deficits and debt center on the rising costs of Social Security payments and Medicare costs, making the use of fiscal policy to mitigate rising debt difficult.

- Rising interest rates in the future will increase borrowing costs, making it more difficult to finance debt. Increased use of expansionary monetary policy can lead to long-run inflation, reducing the debt burden but also reducing the purchasing power of savings.

- Globalization has increased the growth rates of many developing countries. Increased competition from abroad has made it more challenging for developed nations to maintain high growth rates over time.

- Fiscal policies related to trade openness and protectionism along with monetary policies related to exchange rates can affect an economy’s growth rate. However, taking these policies too far can lead to retaliation by trading partners that are adversely affected.

QUESTIONS: In 2009 inflation was negative; average prices fell. The 2007–2009 recession was partly the result of American households carrying too much debt (both in mortgages and on credit cards). Households set out to reduce their debt levels by reducing spending, causing a deeper recession in 2009. Is deflation a help or hindrance to using monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate the economy? Why?

On balance, it is a hindrance when households and businesses attempt to reduce debt levels. Falling prices increase the real value of debt, while declining real income makes it harder to pay off. Declining demand and prices for output provides little incentive for business to invest and expand. Deflation is a symptom of a declining economy and was a concern of monetary policymakers at the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. It is a factor that policy stimulus must overcome.

365