Chapter Introduction

101

102

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Describe the business cycle and some of the important macroeconomic variables that affect the level of economic activity.

- Describe the national income and product accounts (NIPA).

- Describe the circular flow of income and discuss why GDP can be computed using either income or expenditure data.

- Describe the four major expenditure components of GDP.

- Describe the major income components of GDP.

- Describe the shortcomings of GDP as a measure of our standard of living.

Thousands of people lined up near Times Square in New York City early in the morning on April 30, 2010 … not for an audition, not for tickets to a popular concert, not to catch a glimpse of the newest fashion designs, but instead for a job. And not a high-paying job even. These people were seeking a service job at a new hotel that was opening later that summer. Among the over 2,500 applicants, only 300 were hired in a job market that reached the most desperate of conditions in many decades. This was not the Great Depression of the 1930s, but rather the aftermath of the most recent economic downturn of 2007–2009, dubbed the Great Recession.

Although the recession of 2007–2009 was the worst economic downturn in the United States in generations, recessions are not anything new. Over the last 150 years, the U.S. economy has endured more than thirty-three recessions—on average one every four to five years. What made the most recent recession particularly difficult for so many people was its significant impact on employment.

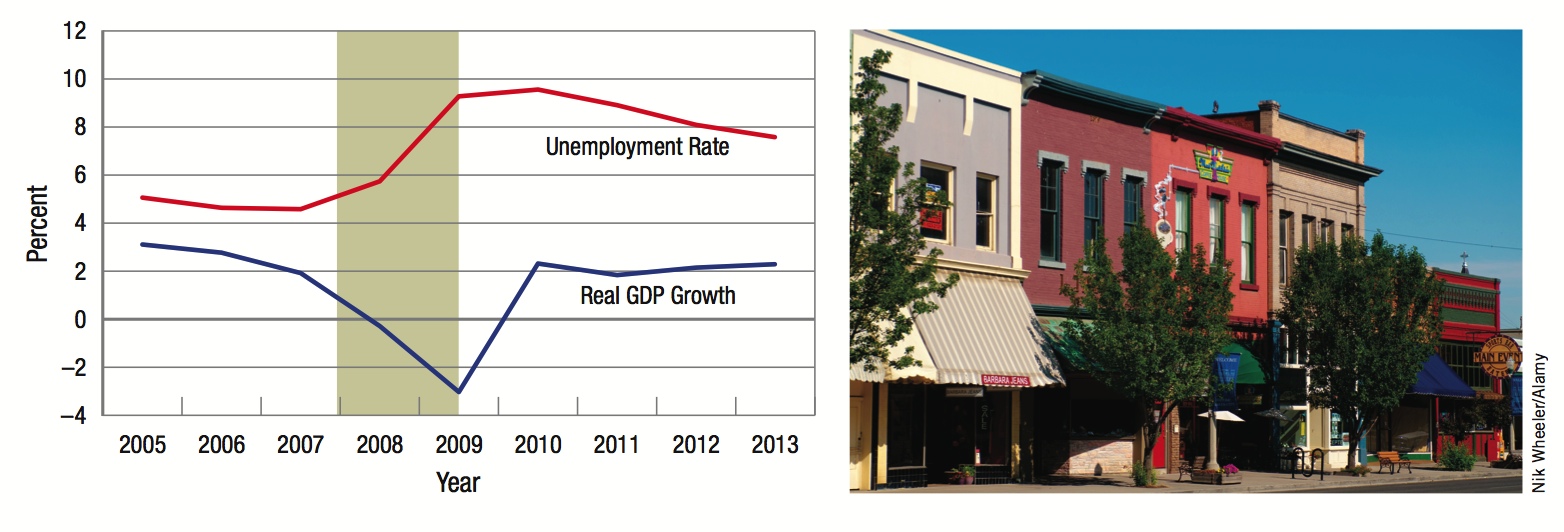

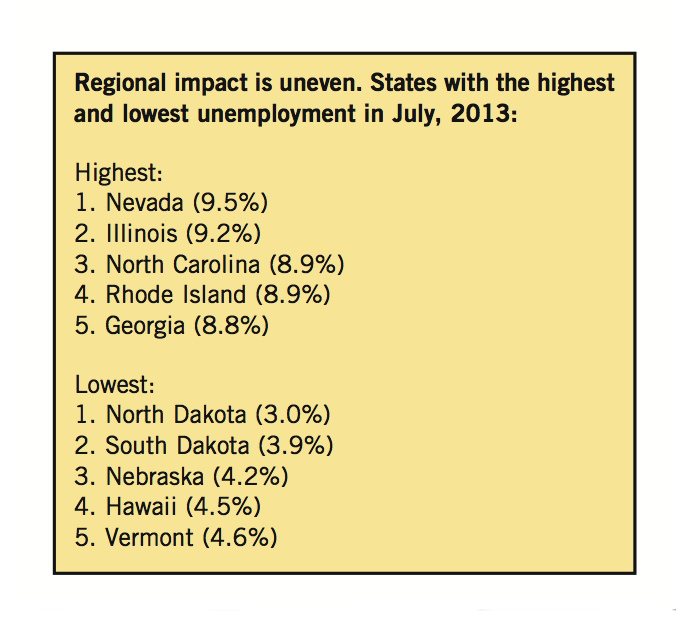

At the height of the recession, one in ten Americans was unemployed. Even more troubling was that as the economy began to recover in the summer of 2009, the unemployment rate did not fall by much. In fact, two years after the end of the recession, the unemployment rate still hovered above 9%; in 2013, four years later, the unemployment rate still exceeded 7%. When an economic recovery produces too few jobs to reduce the unemployment rate significantly, it is known as a jobless recovery.

This jobless recovery had macroeconomists stumped. That was not supposed to happen. Macroeconomics, as a discipline separate from microeconomics, was born out of the need to explain the Great Depression. John Maynard Keynes explained the causes and set forth a framework upon which to develop policies to avoid future severe macroeconomic downturns.

Unemployment was supposed to improve in a recovery. From the 1940s to the 1980s, the recovery from every recession coincided with a sharp increase in job growth and a reduction in the unemployment rate. That changed in the past two decades. The recessions of 1990–1991 and 2001 raised doubts about the resiliency of job growth following a recession. These recent recessions introduced the persistent unemployment associated with jobless recoveries. The recession of 2007–2009 was deeper and had even greater persistent unemployment.

Why did the unemployment rate stay high for so long after the recovery? The answer lies in the many factors affecting labor, capital, product, and financial markets that came together to make the unemployment rate worse during the recession and persistent during the recovery. Furthermore, structural changes in the macroeconomy contributed to the jobless recoveries after the last three recessions.

In the labor market, the collapse of the housing market in 2006 drove construction workers, real estate agents, and mortgage brokers out of work. Those who lost their jobs looked for employment in different industries. But those industries faced difficulties too. The ripple effect of the housing collapse quickly affected financial markets, which then affected capital and product markets, causing unemployment to spread.

In the financial market, when unprecedented numbers of people defaulted on their mortgages, banking institutions faced a crisis. These institutions restricted their lending practices, making it difficult for individuals and firms to borrow money to buy homes and build businesses that would generate jobs. The caution of the banking industry along with new government regulations made the borrowing process more cumbersome.

Businesses create jobs when they predict it will be profitable to do so. They depend on the sales of products and services. However, sales fell as people lost their jobs or faced wage cuts. People in general became pessimistic—even scared—and cut back on their consumption even after the recession ended. Because consumption by individuals represents the largest portion of all spending in the economy, the lack of consumer confidence spilled over to businesses, which in turn became reluctant to hire.

Lastly, high unemployment, lower consumption, and reduced investment by businesses led to decreased income, sales, and property tax revenues for the government. This reduction in tax revenues, coupled with increased government spending, led to large deficits. State and local governments felt the greatest brunt of the deficits, forced to make tough budget cuts that led to massive layoffs in public sector jobs including teaching, law enforcement, and firefighting.

103

The Slow Macroeconomic Recovery

The 2007–2009 recession was the most severe economic downturn to face the United States in over 70 years. Although this recession officially lasted only 18 months, after 48 months of recovery the economy still had not returned to the level of employment and growth seen prior to the recession.

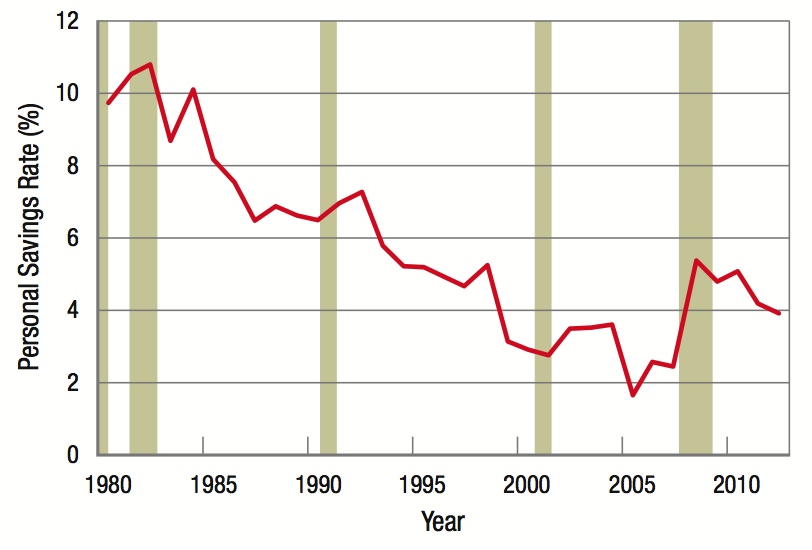

Savings rates have steadily fallen over the last three decades. However, high unemployment and income anxiety, especially during economic downturns, led consumers to tighten their belts and increase savings.

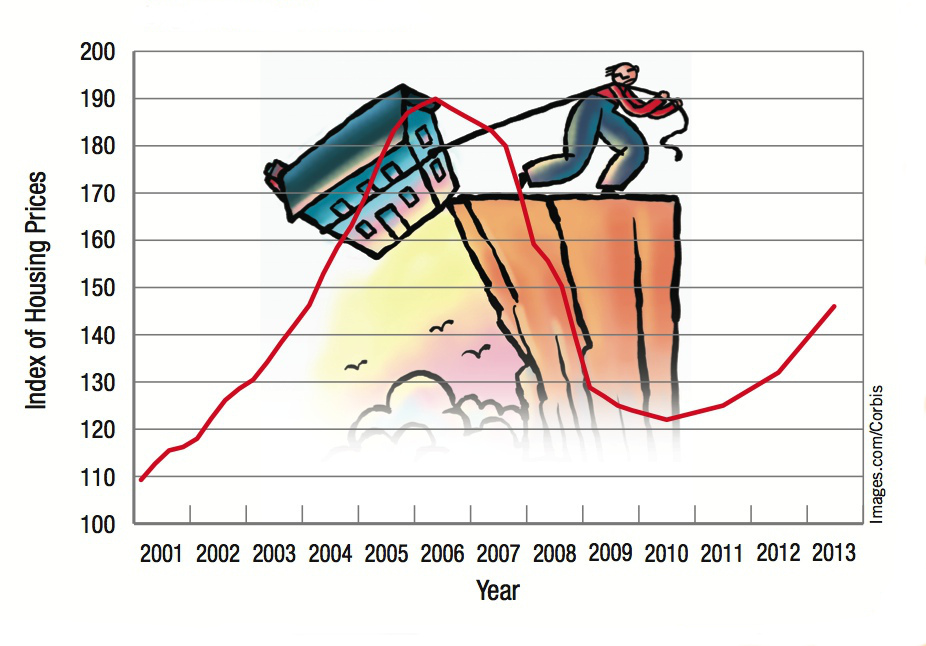

Housing prices rose quickly from 2001 to 2006, then fell dramatically from 2006 to 2010. Prices stabilized in 2010 and have begun to rebound since.

104

The reasons described thus far explain much of—but not the entire—story of jobless recoveries. Additional changes in the macroeconomy over the past two decades contributed to slower job growth. First, the world became much more connected. Recessions tend to spread from one country to another. Competition for jobs intensified due to greater immigration and more companies seeking lower costs by moving production facilities overseas. Second, population growth means more jobs were needed for a country just to stay at its same employment level. Third, pressures to earn profits in a competitive global economy forced businesses to find more efficient means of production, including the use of automation, leading to some job loss as workers are replaced by machines.

It is hard to imagine that such a difficult economic downturn and slow recovery could occur. The Internet boom of the late 1990s and the housing boom of the early 2000s led to low unemployment, rising incomes, and reductions in government deficits. Yet, such ups and downs of the economy are precisely what macroeconomics aims to study.

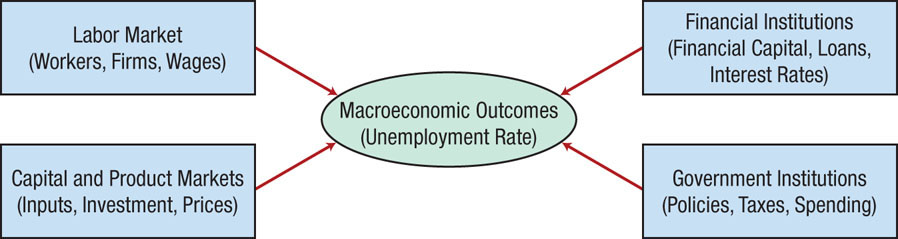

Macroeconomics describes how individuals, businesses, financial institutions, and government institutions interact to achieve the goals of job growth, low inflation, and economic growth. It is not just the conditions of one industry or group of workers that influence macroeconomic outcomes, but rather the conditions of all. Figure 1 illustrates how different markets and institutions come together to influence macroeconomic outcomes such as the unemployment rate.

We have come a long way in our understanding of recessions, but we have a way to go yet. These jobless recoveries reveal that much about the macroeconomy remains difficult to understand. Market forces of demand and supply generally lead prices and output to equilibrium. One hundred years ago, economists thought the same to be true when it came to the overall economy. It was assumed that labor, capital, and product markets would keep the economy near full employment, with small fluctuations in wages, prices, and interest rates helping the economy adjust to disruptions.

The Great Depression, a recession that lasted four years and took nearly a decade to recover from, forced economists to reconsider this earlier way of looking at the macroeconomy. Macroeconomic equilibrium occurs over time through the course of the natural ups and downs termed the business cycle. The development of macroeconomics as a discipline came after the realization of such business cycles and the fact that they can vary significantly in duration and severity.

Most economists believe that the macroeconomy is too complex to function efficiently without policy interventions. Economists have developed many tools for managing the severity of business cycles. Persistent unemployment suggests that economists still do not have all the answers.

This chapter deals with how the macroeconomy is defined and measured. For example, how do economists define and measure business fluctuations? And what are the major statistics collected by government to keep track of the macroeconomy? The first section of this chapter considers how business cycles are defined and measured. The second section looks at the system of national income accounts. These accounts give us our primary measures of income, consumer and government spending, business investment, and foreign transactions, including exports and imports. The last section raises the question of how well the national income accounts measure our standard of living. We look at alternative measures of standard of living, nonmarket transactions, and the effect of environmental degradation and conservation. The foundation established in this chapter will apply to topics covered throughout the course.

105