Inflation

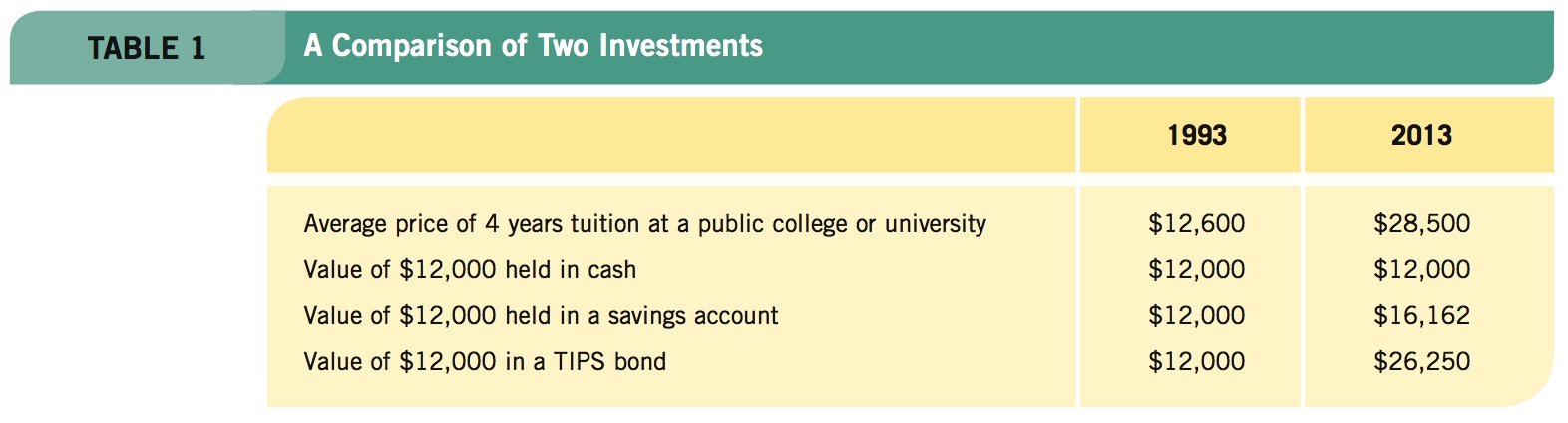

Suppose that 20 years ago, your parents put aside $12,000 each for your and your twin sister’s college education, almost enough money to have paid for four years of tuition at many public universities at that time. Your money was placed into a savings account that earned 1.5% interest per year on average, and your sister’s money was placed into a Treasury Inflation-Protected Security (TIPS) bond, which pays a fixed interest rate but whose value also changes with the inflation rate. Now you and your sister withdraw the money to pay for college. Big problem: The cost of tuition has more than doubled in the 20 years since your parents put the money into your accounts. Do you both still have enough to pay your tuition bill? Your sister perhaps does, but not you. Your account has $16,162 in it, and your sister’s account has $26,250. Looks like your sister got the better deal.

129

The Twin Evils of Inflation and Unemployment

Inflation and unemployment are two variables that governments monitor carefully. Nearly every country has experienced periods of very high unemployment or inflation at some point in its past, and government policies used to correct these problems vary significantly.

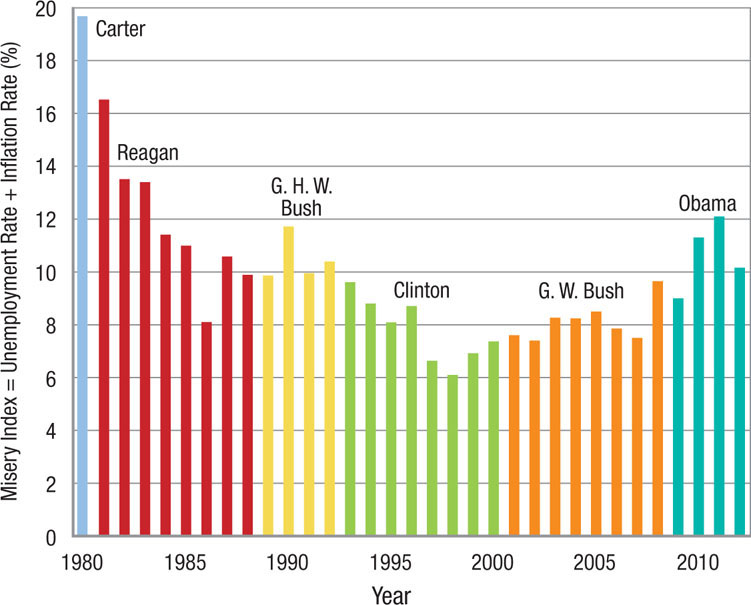

Do Unemployment and Inflation Measure Our Misery?

The Misery Index was created by economist Arthur Okun, an adviser to President Lyndon Johnson. It is the sum of the unemployment and inflation rates. The higher the number, the more misery the economy is suffering. Running against Gerald Ford for the presidency in 1976, Jimmy Carter made an issue of the Misery Index: It was 13%. He argued that no one should be reelected as president when the Misery Index is that high. When Carter sought reelection in 1980, the Misery Index approached 20%; he lost to Ronald Reagan.

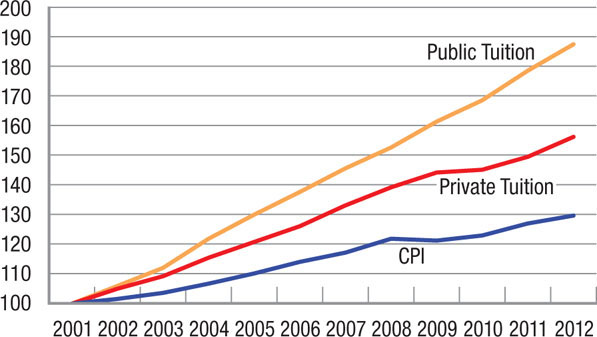

The cost of tuition at public and private colleges and universities has risen faster than the consumer price index for all goods and services since 2001. (Index = 100 in year 2001.)

The social costs of unemployment: For every 1% rise in the national unemployment rate:

- $30 billion more is spent by the government on unemployment benefits per year.

- $6 billion more is spent on food stamps (SNAP benefits) per year.

- $12 billion less is collected in federal and state income tax revenues per year.

In addition, rising unemployment causes:

- More people to be underemployed

- An increase in alcoholism and depression

- A general increase in crime

- Greater calls for protectionist trade policies

inflation A measure of changes in the cost of living. A general rise in prices throughout the economy.

130

Prices are constantly changing for the goods and services we buy. Prices for items such as concert tickets, airline tickets, and fast food meals have steadily risen over time, making every dollar earned worth a little less in terms of how much it can buy. Some goods, such as smartphones, laptops, and other technology goods, however, have fallen in price. Overall, the prices of a typical “basket” of goods and services we buy rise each year—by 43% over the last 15 years, and 660% over the last 50 years. This gradual rise in prices each year is known as inflation. Over time, the effects of inflation can be substantial if one does not take action to protect against rising prices. For example, paying $4 a gallon for gasoline today is much harder than paying $1.25 a gallon was back in 1998. But it would be even harder if your wages or savings have not increased over that period.

How do individuals protect themselves against rising prices? First, workers demand higher wages to compensate for higher prices. But in a weak economy, wage increases are not always possible, especially when many people are out of work and willing to work for lower wages. Second, individuals with money saved can invest that money in assets that earn interest or can increase in value over time. Holding cash, for example, does not earn interest and therefore does not protect one against inflation.

Many forms of assets pay interest, including savings accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), bonds, and money market accounts. But they do not pay equal amounts—safer assets, such as savings accounts, pay less than the average rise in prices, while riskier assets might pay more than the average rise in prices. One asset that pays a rate roughly equal to the rise in prices are TIPS bonds, which pay a small fixed interest rate in addition to an adjustment based on how prices change in an economy. Therefore, when prices do not rise much, a TIPS bond would pay little, but when prices rise a lot, a TIPS bond will pay a lot. Table 1 shows how $12,000 placed into different assets would have grown over 20 years. The TIPS bond better ensures that when you take money out after 20 years, you will be more able to pay for college at the higher prices.

What Causes Inflation?

Inflation is a measure of changes in the cost of living. In an economy like ours, prices are constantly changing. Some go up as others go down, and some prices rise and fall seasonally. Inflation is caused by many different factors, but the primary reasons can be attributed to demand factors, supply shocks, and government policy.

First, prices for goods and services are influenced by demand factors such as consumer confidence, income, or wealth. Think of a busy mall or restaurant. When there are plenty of customers, businesses are not pressured to offer discounts to attract buyers. This keeps prices higher than when consumer demand is depressed. For this reason, economic growth tends to coincide with inflation as a result of the demand for goods and services that higher incomes produce.

131

Emile Wamsteker/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Reed Saxon/AP

Second, prices are affected by supply shocks, caused by fluctuations in the price of inputs such as oil and natural resources. Less than a decade ago, the average price of a gallon of gasoline was under $2. But over the past decade, tremendous growth in China and India has led to a huge increase in demand for oil, which increased the price of gasoline. Rapidly rising oil prices directly raise the cost of living for individuals, but also, oil is an important input used in the production of electricity and plastics, and also to transport goods once produced. Higher oil prices therefore raise the costs of doing business, which get passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

Lastly, inflation can result from specific government actions. Government has a great power that no one individual has—the power to print money. No doubt you have heard that the federal government runs a budget deficit: It spends more than it receives in tax revenues. How does it get the money to overspend? It borrows by issuing Treasury bonds. When the bonds come due and the government does not have the money to buy them back, it can, in essence, run the printing presses and print up new dollars. As more new money is printed, a surplus of dollars is generated in relation to the supply of goods and services. When too much money chases a fixed quantity of goods and services, prices are bid up, which leads to inflation. Governments, like everyone else, have to obey the laws of supply and demand by limiting the growth of the money supply to prevent rampant inflation from occurring.

Now that we have described the main causes of inflation, let’s discuss how inflation is measured.

Measuring Inflation: Consumer Price Index, Producer Price Index, and GDP Deflator

price level The absolute level of a price index, whether the consumer price index (CPI; retail prices), the producer price index (PPI; wholesale prices), or the GDP deflator (average price of all items in GDP).

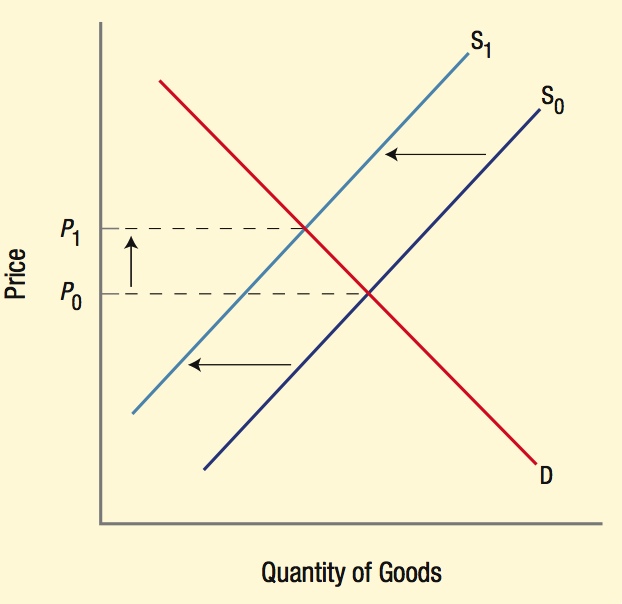

disinflation A reduction in the rate of inflation. An economy going through disinflation typically is still facing inflation, but at a declining rate.

Each month, the U.S. Department of Labor, through its Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), reports several important statistics that provide us with our principal measure of inflation. It does so by reporting changes in the average level of prices over the previous month in terms of the price level. The price level is the absolute level of a price index, whether this is the CPI (retail prices), the producer price index (PPI; wholesale prices), or the GDP deflator (average price of all items in GDP). The percentage increase in prices over a 12-month period is referred to as the rate of inflation.

deflation A decline in overall prices throughout the economy. This is the opposite of inflation.

Because inflation rates fluctuate up and down, the term disinflation is used to describe a reduction in the rate of inflation. Note that an economy going through disinflation still experiences rising prices, just at a slower pace. This was the case from the mid-1980s throughout the 1990s. However, if overall prices in an economy actually fall, this is referred to as deflation. Cases of deflation are rare, but did occur in the early 1930s.

Measuring consumer spending and inflation is one of the oldest data-collection functions of the BLS. According to the BLS Handbook of Methods, “The first nationwide expenditure survey was conducted in 1888–91 to study workers’ spending patterns as elements of production costs… it emphasized the worker’s role as a producer rather than as a consumer.”1 During World War I, surveys of consumer spending were conducted to compute one of the first cost-of-living indices. During the Great Depression, extensive consumer surveys were used to study the welfare of selected groups, notably farmers, rural families, and urban families. The BLS began regular reports of the modern CPI in the late 1930s. Today, the CPI is the measure of inflation most Americans are familiar with, although the producer price index and the GDP deflator also are widely followed.

consumer price index (CPI) A measure of the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a typical market basket of consumer goods and services.

132

The Consumer Price Index The consumer price index (CPI) measures the average change in prices paid by urban consumers (CPI-U) and urban wage earners (CPI-W) for a market basket of consumer goods and services. The CPI-U covers roughly 87% of the population.

The CPI is often referred to as a “cost-of-living” index, but the current CPI differs from a true cost-of-living measure. A cost-of-living index compares the cost of maintaining the same standard of living in the current and base periods. A cost-of-goods index, in contrast, merely measures the cost of a fixed bundle of goods and services from one period to the next.

Why does CPI use a fixed bundle of goods and services? First, this avoids having to measure how consumers react to price changes; for example, if the price of beef rises, people might buy more chicken. Second, because it is difficult to follow every decision made by consumers, the government measures how prices change for a fixed basket of goods that an average consumer would buy.

The CPI is calculated by dividing the market basket’s cost in the current period by its cost in the base period. The current CPI is a cost-of-goods index because it measures changes in the price of a fixed basket of goods. The reference or base period used today for the CPI is 1982–1984, but any base year would work just as well.

How the Bureau of Labor Statistics Measures Changes in Consumer Prices Measuring consumer prices requires the work of many people. Data collectors record about 80,000 prices in 87 urban areas each month from selected department stores, supermarkets, service stations, doctors’ offices, rental offices, and more. Yet, the BLS does not have enough resources to price all goods and services in all retail outlets; therefore, it uses three sample groups to approximate the spending behavior of all urban consumers. These include a Consumer Expenditure Survey tracking the spending habits of over 30,000 families nationwide used to construct the market basket of goods and services, a Point-of-Purchase Survey that identifies where households purchase goods and services, and census data to select the urban areas where prices are collected.

Goods and services are divided into more than 200 categories, with each category specifying over 200 items for monthly price collection. Data from the three surveys are combined, weighted, and used to compute the cost in the current period required to purchase the fixed market basket of goods. This cost is then compared to the base period to calculate the CPI using the following formula:

CPI = (Cost in Current Period ÷ Cost in Base Period) × 100

For example, assume that the market basket of goods cost $5,000 in 2008 and that the same basket of goods now costs $5,750. The CPI for today, using 2008 for the base year, is:

115.0 = ($5,750 ÷ $5,000) × 100.

Therefore, the cost of goods has risen by 15% over this time period because the index in the base year (2008 in this case) is always 100. Again, the choice of base year does not matter as long as the CPI for each year is calculated relative to the cost in the selected base year. In fact, one can use CPI data as reported by the BLS to calculate price changes between any two years, neither of which is the base year, using the following formula:

% Change in Price = [(CPI in Current Year / CPI in Original Year) × 100] − 100

For example, if the CPI in 2013 was 233.8 and the CPI in 2008 was 215.3, the average change in prices over this five-year period was:

8.6% = [(233.8 / 215.3) × 100] − 100.

We now take a quick look at some of the problems inherent in the current approach to measuring the CPI.

133

Problems in Measuring Consumer Prices The CPI is a conditional cost-of-goods index in that it measures only private goods and services; public goods (such as national defense spending) are excluded. Other background environmental factors, meanwhile, are held constant. The current CPI, for instance, does not take into account such issues as the state of the environment, homeland security, life expectancy, crime rates, climate change, or other conditions affecting the quality of life. For these reasons alone, the CPI will probably never be a true cost-of-living index.

But even if we ignore the environmental factors and public services, the CPI still tends to overstate inflation for three key reasons: product substitution, quality improvements, and the introduction of new products.

The CPI uses a fixed market basket determined by consumer expenditure surveys that often are three to five years old. The CPI assumes that consumers continue to purchase the same basket of goods from one year to the next. We know, however, that when the price of one good rises, consumers substitute other goods that have fallen in price, or at least did not rise as much.

Also, in any given year, about 30% of the products in the market basket will disappear from store shelves.2 Data collectors can directly substitute other products for roughly two-thirds of these dropped products, which means that about 10% of the original market basket must be replaced by products that have been improved or modified in some important way. These quality improvements affect standards of living although they are not fully accounted for in CPI measurements.

Another problem for CPI is the introduction of new products. Not too long ago, digital streaming of books, music, and movies did not exist. Neither did iPads and other devices allowing these media to be played. Because technology is constantly changing along with the prices of technology goods, the BLS often waits until a product matures and is used by a significant number of consumers before including it in the market basket. By not measuring the benefits of new products that consumers enjoy, this again will overstate the actual rate of inflation.

One final difficulty to note has to do with measuring the changing costs of health care. The CPI looks only at consumers’ out-of-pocket spending on health care, and not the overall health care spending (including payments made by Medicare, Medicaid, and employer-provided insurance), which is 3 times larger. If price changes differ between out-of-pocket spending and total spending, the CPI will not reflect the true rise in costs.

One solution to these problems was the introduction of a new indicator by the BLS called C-CPI-U, or chained CPI for urban consumers. The C-CPI-U uses the same data as the CPI-U but applies a different formula to account for product substitutions made by consumers. Although the C-CPI-U does a better job at approximating a cost-of-living index, it takes longer to estimate because data must be collected over several years. The BLS reports the C-CPI-U, which has a base period of 1999, alongside CPI-U and CPI-W.

producer price index (PPI) A measure of the average changes in the prices received by domestic producers for their output.

The difference in magnitudes between CPI-U and C-CPI-U vary from year to year; however, the trend has been for C-CPI-U to be lower than CPI-U by roughly 0.3% to 0.4% each year.

The Producer Price Index The producer price index (PPI) measures the average changes in the prices received by domestic producers for their output. Before 1978 this index was known as the wholesale price index (WPI). The PPI is compiled by doing extensive sampling of nearly every industry in the mining and manufacturing sectors of our economy.

The PPI contains the following:

- Price indexes for roughly 500 mining and manufacturing industries, including over 10,000 indexes for specific products and product categories.

- Over 3,200 commodity price indexes organized by type of product and end use.

- Nearly 1,000 indexes for specific outputs of industries in the service sector, and other sectors that do not produce physical products.

- Several major aggregate measures of price changes, organized by stage of processing, both commodity based and industry based.3

134

GDP deflator An index of the average prices for all goods and services in the economy, including consumer goods, investment goods, government goods and services, and exports. It is the broadest measure of inflation in the national income and product accounts (NIPA).

The PPI measures the net revenue accruing to a representative firm for specific products. Because the PPI measures net revenues received by the firm, excise taxes are excluded, but changes in sales promotion programs such as rebate offers or zero-interest loans are included. Because the products measured are the same from month to month, the PPI is plagued by the same problems discussed above for the CPI. These problems include quality changes, deleted products, and some manufacturers exiting the industry.

The GDP Deflator The GDP deflator shown in Figure 1 is our broadest measure of inflation. It is an index of the average prices for all goods and services in the economy, including consumer goods, investment goods, government goods and services, and exports. The prices of imports are excluded. Note that deflation occurred in the Great Depression. The spike in inflation occurred just after the end of World War II, when price controls were lifted. Since the mid-1980s, the economy has witnessed disinflation—inflation was present but generally at a decreasing rate.

Adjusting for Inflation: Escalating and Deflating Series (Nominal Versus Real Values)

Price indexes are used for two primary purposes: escalation and deflation. An escalator agreement modifies future payments, usually increasing them, to take the effects of inflation into account. Deflating a series of data with an index involves adjusting some current value (often called the nominal value) for the impact of inflation, thereby creating what economists call a real value. Using the GDP deflator, for instance, to deflate annual GDP involves adjusting nominal GDP to account for inflation, thereby yielding real GDP, or GDP adjusted for inflation.

Escalator Clauses Many contracts, including commercial rental agreements, labor union contracts, and Social Security payments are subject to escalator clauses. An escalator clause is designed to adjust payments or wages for changes in the price level. Social Security payments, for example, are adjusted upward almost every year to account for the rate of inflation.

135

Escalator clauses become important in times of rising or significant inflation. These clauses protect the real value of wages as well as payments such as Social Security. In fact, voting blocs and organizations such as AARP have been formed to protect those who depend on escalator clauses to maintain their standards of living.

Deflating Series: Nominal Versus Real Values GDP grew by 24% from 2005 to 2013, but should we be celebrating? Not really, because inflation has eroded the purchasing power of that increase. The question is, by how much did GDP really increase?

First, remember that every index is grounded on a base year, and that the value for this base year is always 100. The base year used for the GDP deflator, for instance, is 2005. The formula for converting a nominal value, or current dollar value, to real value, or constant dollar value, is

Real = Nominal × (Base Year Index ÷ Current Year Index)

To illustrate, nominal GDP in 2013 was $16,633.4 billion. The GDP deflator, having been 100 in 2005, was 116.1 in 2013. Real GDP for 2013 (in 2005 dollars) was therefore:

$14,326.8 billion = $16,633.4 billion × (100.0 ÷ 116.1).

Note that because the economy has faced some inflation—16.1% from 2005 to 2013—the nominal value of GDP has been reduced by this amount to arrive at the real value. In other words, of the 24% growth in nominal GDP, 16.1% was due to rising prices. If we subtract 16.1% from 24%, real growth of GDP from 2005 to 2013 was less than 8%, or about 1% per year. The recession of 2007–2009 played a large role in the very slow growth of real GDP over this time period.

The Effect of Overstating Inflation Many federal benefits, including Social Security payments, food stamps, and veterans’ benefits, are indexed to the CPI, which means that if inflation (as measured by the CPI) goes up by 3%, these benefits are increased by 3%. If the CPI overstates inflation, federal expenditures on benefits are higher. Although individuals initially benefit from the higher payments, overstating inflation in the long run makes real earnings appear smaller than what they actually are. This leads to a different set of issues for policymakers and our economy.

Because CPI had been estimated to overstate inflation, in 1999 the Department of Labor revised its measurement tools used for estimating inflation. As a result, today’s CPI is a more accurate measure of inflation.

The Consequences of Inflation

Why do so many policymakers, businesspeople, and consumers dread inflation? Your attitude toward inflation will depend in large part on whether you live on a fixed income, whether you are a creditor or debtor, and whether you have properly anticipated inflation.

Many elderly people live on incomes that are fixed; often, only their Social Security payments are indexed to inflation. People on fixed incomes are harmed by inflation because the purchasing power of their income declines. If people live long enough on fixed incomes, inflation can reduce them from living comfortably to living in poverty.

Creditors, meanwhile, are harmed by inflation because both the principal on loans and interest payments are usually fixed. Inflation reduces the real value of the payments they receive, while the value of the principal declines in real terms. This means that debtors benefit from inflation; the real value of their payments declines as their wages rise with inflation. Many homeowners in the 1970s and 1980s saw the value of their real estate rise from inflation. At the same time, their wages rose, again partly due to inflation, but their mortgage payment remained fixed. The result was that a smaller part of the typical household’s income was needed to pay the mortgage. Inflation thus redistributes income from creditors to debtors.

136

This result takes place only if the inflation is unanticipated. If lenders foresee inflation, they will adjust the interest rates they offer to offset the inflation expected over the period of the loan. Suppose, for instance, that the interest rate during zero inflation periods is roughly 3%. Now suppose that a lender expects inflation to run 5% a year over the next three years, the life of a proposed loan. The lender will demand an 8% interest rate to adjust for the expected losses caused by inflation. Only when lenders fail to anticipate inflation does it harm them, to the benefit of debtors.

But the effects of unexpected inflation do not stop there. When inflation is unexpected, the incentives individuals and firms face change. For example, suppose that inflation causes prices of everyday purchases along with wages to increase by 5%. If this inflationary effect was anticipated, then consumption decisions should not change, because real prices stay the same when prices and wages rise by the same amount. But if the price rise was unexpected, it might cause consumers to reduce their consumption, leading to lower spending in the economy. For firms, if an increase in money due to unexpected inflation causes demand for their products to rise at their original prices, firms might react by increasing production (and their costs) rather than adjusting their prices when actual demand has not changed. Therefore, unexpected inflation leads to faulty signals, which can reduce consumer and producer welfare.

Lastly, when inflation becomes rampant, individuals and firms expend resources to protect themselves from the harmful effects of rapidly rising prices, an effect that is especially prevalent in cases of hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation

hyperinflation An extremely high rate of inflation; above 100% per year.

Hyperinflation is an extremely high rate of inflation. Today, most economists refer to an inflation rate above 100% a year as hyperinflation. But in most episodes of hyperinflation, the inflation rates dwarf 100% a year. In 2008 in Zimbabwe, prices were more than doubling every day, for an annual inflation rate of 231,000,000%.

Hyperinflation is not new. It has been around since paper money and debt were invented. During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress issued money until the phrase “not worth a continental” became part of the language. Germany experienced the first modern hyperinflation after World War I. Hungary experienced the highest rate of inflation on record during World War II. By the end of the war, it took over 800 octillion (8 followed by 29 zeros) Hungarian pengos to equal 1 prewar pengo.

Hyperinflation is usually caused by an excess of government spending over tax revenues (extremely high deficits) coupled with the printing of money to finance these deficits. Post–World War I Germany faced billions of dollars in war reparations that crippled the country. The German government found it difficult to collect enough taxes to pay the reparations, and instead it simply printed more money, causing the value of the currency to fall as prices rose. Over time, financial assets in banks and pension accounts became worthless and were essentially taxed away through hyperinflation.

Stopping hyperinflation requires restoring confidence in the government’s ability to bring its budget under control. It usually requires a change in government and a new currency, and most important a commitment to reduce the growth of the money supply.

137

The Consequences of Counterfeit Money on Inflation

Each day, hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars exchange hands in everyday transactions. A small fraction of these dollars are counterfeit, circulating throughout the economy as if they were genuine. When counterfeit money is created, who ends up paying for it?

Suppose you receive some money, and later realize one of the bills is fake (the ink runs, the paper is too thin, or the watermark is missing). What can you do? Many people assume they could go to a bank and exchange the fake bill for a real one. But most banks won’t accept a fake bill because then the bank would lose the money. Some people pass the fake to the next unsuspecting person, but this is a punishable offense. The law states that a counterfeit bill must be reported to the nearest U.S. Secret Service field office. By doing so, you still lose the money, as there is no compensation for turning in counterfeit money.

Thus, the responsibility lies with individuals and businesses to check the authenticity of the money received, and to refuse money that appears to be counterfeit. That is not always as easy as it sounds. A low-quality counterfeit might be detected by the naked eye or by touch, especially with the use of devices such as a counterfeit detector pen. But sophisticated counterfeiters produce high-quality counterfeits that are hard to detect. For example, one counterfeiting method has been to remove the ink from a lower denomination bill and then reprint a higher denomination on the paper. The paper is real, making counterfeit detector pens ineffective, and the bill contains a watermark (however, the wrong one) and a security strip. These counterfeits are nearly indistinguishable from authentic bills, and can circulate for years without being noticed.

Who ultimately loses when counterfeit money is circulated? For low-quality bills, it is the last person to accept it. Restaurants and other businesses often receive counterfeits because cashiers are rushed. Consumers sometimes pass them to businesses thinking it won’t hurt them. Because banks generally do not accept counterfeits, businesses with counterfeits end up losing.

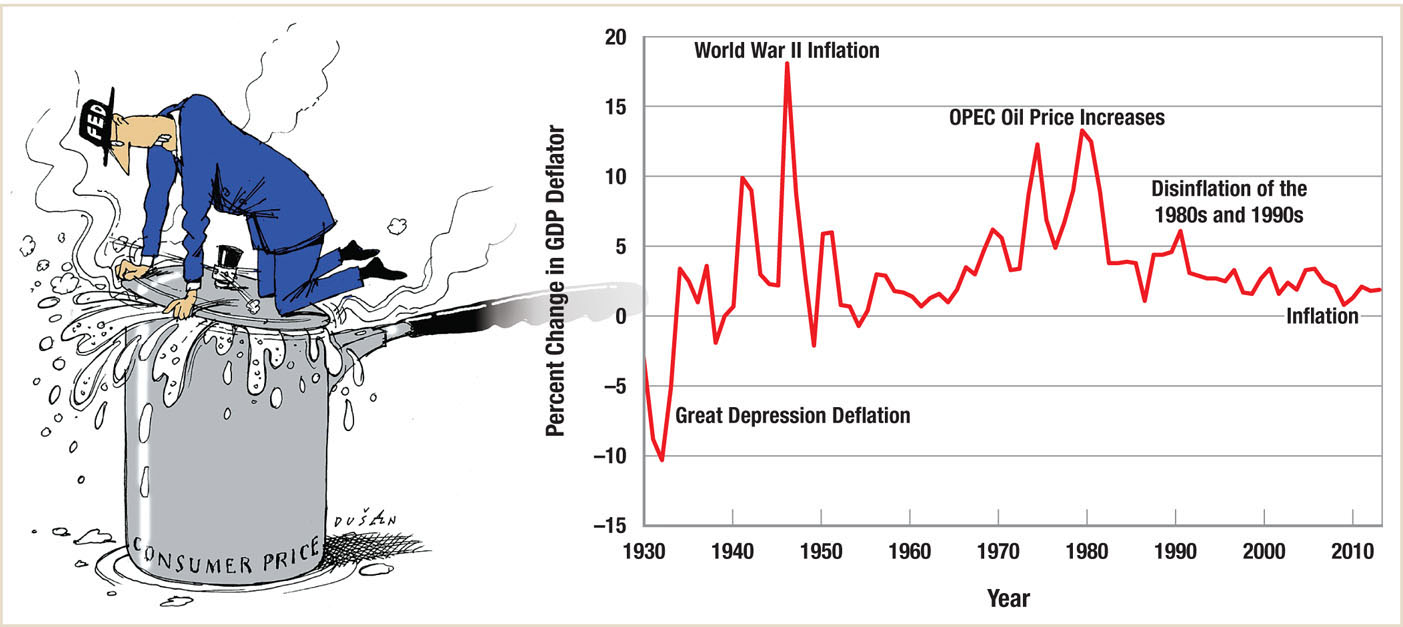

When a business incurs a loss due to counterfeit money, this acts as a tax on the business. In other words, the supply curve shifts to the left, and prices rise. Therefore, even if individuals do not end up with the counterfeit in their possession, they pay for them in the form of higher prices.

What happens when a high-quality counterfeit circulates for years in the economy; is it really fake? Literally, yes, but in terms of its economic impact, counterfeit money acts as real money if people accept it as real money. Ultimately, the government loses. Why? The government (the U.S. Treasury to be specific) is the only institution with the authority to print money. When another entity prints counterfeits, the amount of money in circulation rises, but the government never had the opportunity to use it first.

When more money chases a limited amount of goods and services in an economy, inflation arises. Because counterfeits produce the same effect as an increase in the money supply, inflation will occur. In sum, counterfeits hurt everyone, which is why governments invest in new technology to produce money with many security features.

Hyperinflation is an extreme case, yet it shows how inflation can have detrimental effects on an economy. This is why it is important to keep track of inflation, as it is an important measure of the health of an economy.

138

INFLATION

- Inflation is a measure of the change in the cost of living.

- Inflation is a general rise in prices throughout the economy.

- Disinflation is a reduction in the rate of inflation, and deflation is a decline in overall prices in the economy.

- The CPI measures inflation for urban consumers and is based on a survey of a fixed market basket of goods and services each month.

- The PPI measures price changes for the output of domestic producers.

- The GDP deflator is the broadest measure of inflation and covers all goods and services in GDP.

- Escalator clauses adjust payments (wages, rents, and other payments such as Social Security) to account for inflation.

- Real (adjusted for inflation) values are found by multiplying the nominal (current dollar) values by the ratio of the base year index to the current year index.

- Hyperinflation is an extremely high rate of inflation.

QUESTION: Suppose you took out $20,000 in student loans at a fixed interest rate of 5%. Assume that after you graduate, inflation rises significantly as you are paying back your loans. Does this rise in inflation benefit you in paying back your student loans? Who is hurt more from unexpected higher inflation—a borrower or a lender?

Inflation makes the value of a dollar fall in purchasing power. Therefore, if you borrow money when inflation is low and pay back the loan when inflation is higher, the money you are paying back is worth less than what you received. You benefit by being able to pay back your loans with money that is valued at less than before. Thus, unexpected inflation hurts lenders because the money they are being paid back is worth less in purchasing power than they had planned. Alternatively, had the inflation rate unexpectedly fallen, lenders would gain, as the money being paid back would be worth more in purchasing power than was expected.