Competitive Labor Supply

Economists divide your activities into two categories: work and leisure. When you decide to work, you are giving up leisure, understood broadly as nonwork activity, in exchange for the income that work brings. Economists assume people prefer leisure activities to work. This may not be entirely true, as work can be a source of personal satisfaction and a network of social connections, as well as provide many other benefits. For our discussion, however, we follow the practice of economists in dividing individual or household time into just work and leisure. Note that the term leisure encompasses all activities that do not involve paid work, including caring for children, doing household chores, and activities that are truly leisurely.

Individual Labor Supply

supply of labor The amount of time an individual is willing to work at various wage rates.

The supply of labor represents the time an individual is willing to work—the labor the individual is willing to supply—at various wage rates. On a given day, the most a person can work is 24 hours, although clearly such a schedule could not be sustained for long, given that we all need rest and sleep. For high wages, you would probably be willing to work horrendous hours for a short time, whereas if wages were low enough, you might not be willing to work at all. Between these two extremes lies the normal supply of labor curve for most people.

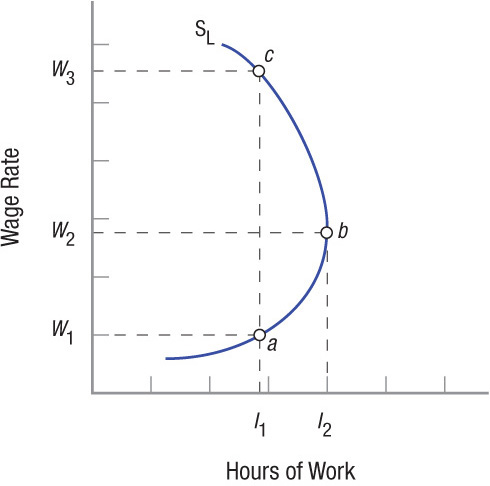

Figure 1 shows a typical labor supply curve for individuals. This individual is willing to supply l1 hours of work per day when the wage is W1. What happens if the wage rate increases? Assume that wages increase to W2: This individual now is willing to increase hours spent working from l1 to l2 (point b). But if the wage rate increases further to W3, this individual reduces the hours spent working back to l1 (point c). What determines how many hours a person is willing to work at each wage rate?

FIGURE 1

Individual Supply of Labor When wages are W1, this individual will work l1 hours, but when the wage rate rises to W2, her willingness to work rises to l2. Over these two wage rates she is substituting work for leisure. Once the wage rises above W2, the income effect begins to dominate, since she now has sufficient income that leisure is now more important and her labor supply curve is backward bending.

substitution effect Higher wages mean that the value of work has increased, and the opportunity costs of leisure are higher, hence work is substituted for leisure.

Substitution Effect When wages rise, people tend to substitute work for leisure because the opportunity cost of leisure grows. This is known as the substitution effect. The substitution effect for labor supply is always positive; it leads to more hours of work when the wage rate increases.

279

Note that this effect is similar to the substitution effect consumers experience when the price of a product declines. When the price of one product falls, consumers substitute that product for others. The substitution effect for consumer products, however, is negative (price falls and consumption rises), while it is always positive for labor (wages rise and the supply of labor increases).

income effect Higher wages mean that you can maintain the same standard of living by working fewer hours. The impact on labor supply is generally negative.

Income Effect When wages rise, if you continue to work the same hours as before, your income will rise. As income rises, you have an ability to purchase more goods, including leisure. Thus, as wages rise to a level high enough to live the lifestyle you wish, you might desire to reduce the hours you work (besides, if you work too much you won’t have time to enjoy spending the money you earned). This notion of working less (and consuming more leisure) as wages rise is known as the income effect. The income effect on labor supply is normally negative—higher wages and income lead to fewer hours worked as individuals desire more leisure. This effect counteracts the substitution effect, which encourages individuals to work more as wages rise.

Both the substitution and income effects are present for all individuals, but at varying levels. The individual supply of labor, therefore, depends on which effect is stronger at each wage rate, and the individual labor supply curve is backward bending as shown in Figure 1.

When the labor supply curve is positively sloped, as it is below W2 in Figure 1, the substitution effect is stronger than the income effect; income is more important than leisure at these wage levels, thus, higher wages lead to more hours worked. Conversely, when the supply of labor curve bends backward, as it does above W2, the income effect overpowers the substitution effect. In this case, higher wages mean fewer hours worked.

Backward bending labor supply curves have been observed empirically in developed and developing countries. Still, it takes rather high income levels before the income effect begins to overpower the substitution effect. People like to have incomes well beyond what is required to satisfy their basic needs before they select more leisure over work as wages rise.

Market Labor Supply Curves

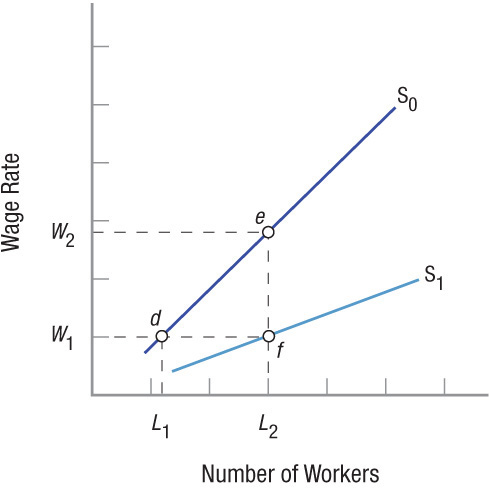

The labor supply for any occupation or industry is upward sloping; higher wages for a job mean more inquiries and job applications. Thus, although an individual’s labor supply curve may be backward bending, market labor supply curves are normally positively sloped as shown in Figure 2. Note that this is true for all other inputs to the production process, including raw materials such as copper, steel, and silicon, as well as for capital and land: Higher prices mean higher quantities supplied.

FIGURE 2

Market Labor Supply Market labor supply is positively related to the wage rate. Increasing wages in one industry attract labor from other industries (a movement from point d to point e as the wage rises from W1 to W2). In contrast, market labor supply curves shift in response to demographic changes, changes in the nonwage benefits of jobs, wages paid in other occupations, and nonwage income.

280

Changes in wage rates change the quantity of labor supplied. For example, increasing wages in one industry attract labor from other industries. This is a movement along the market labor supply curve, shown as a movement along S0 from points d to e as wages (input prices) rise from W1 to W2.

Factors That Change Labor Supply

What factors will cause the entire market labor supply curve to shift from, say, S0 to S1 in Figure 2 so that L2 workers are willing to work for a wage of W1 (point f)? These include demographic changes, nonwage benefits of jobs, wages paid in other occupations, and nonwage income.

Demographic Changes Changes in population, immigration patterns, and labor force participation rates (the percentage of individuals in a group who enter the labor force) all change labor supplies by altering the number of qualified people available for work.

Over the past three decades, labor force participation rates among women have steadily risen, continually adding workers to the expanding American labor force; dual-earner households are increasingly the norm. Today, both parents work in about 60% of all married-couple households with children.

Another demographic change is the increasing portion of population growth in the United States resulting from immigration (both legal and illegal). Over 80% of net population growth over the next four decades will result from immigrants and their U.S.-born descendants.1 This will have a significant effect on the labor supply.

Finally, other demographic changes have shifted the labor supply curve by modifying the labor—leisure preferences among workers. Health improvements, for example, have lengthened the typical working life, thereby increasing the supply of labor.

Nonmoney Aspects of Jobs Changes in the nonwage benefits of an occupation will similarly shift the supply of labor in that market. If employers can manage to increase the pleasantness, safety, or status of a job, labor supply will increase. Other nonmoney perks also help. The airline industry, for example, has greatly increased the number of people willing to work in mundane positions by allowing employees to fly anywhere free.

Wages in Alternative Jobs When worker skills in one industry are readily transferable to other jobs or industries, the wages paid in those other markets will affect wage rates and the labor supply in the first industry. For example, Web site designers and computer technicians are useful in all industries, and their wages in one industry affect all industries. Because at least some of the skills that all workers possess will benefit other employers, all labor markets have some influence over each other. Rising wages in growth industries will shrink the supply of labor available to firms in other industries.

281

Nonwage Income Changes in income from sources other than working (such as income from a trust) will change the supply of labor. As nonwage income rises, hours of work supplied declines. If you have enough income from nonwork sources, after all, the retirement urge will set in no matter what your age.

The key thing to remember here is that market labor supply curves are normally positively sloped, even though an individual’s labor supply curve may be backward bending. In the next section, we put this together with the other blade of the scissors: the demand for labor in competitive labor markets.

COMPETITIVE LABOR SUPPLY

- Competitive labor markets assume that firms operate in competitive product markets and purchase homogeneous labor, and that information is widely available and accurate.

- The supply of labor represents the time an individual is willing to work.

- The substitution effect occurs when wages rise, as people tend to substitute work for leisure because the opportunity cost of leisure is higher, or vice versa when wages fall.

- When wages rise and you continue to work the same number of hours, your income rises. When wages rise high enough, an income effect occurs in which income is traded for leisure, and the supply of labor curve for individuals is backward bending.

- Industry or occupation labor supply curves are upward sloping.

- The labor supply curve shifts with demographic changes, changes in the nonwage aspects of an occupation, changes in the wages of alternative jobs, and changes in nonwage income.

QUESTION: Assume that you take a job with flexible hours, but initially your salary is based on a 40-hour week. Your salary begins at $15 an hour, or $30,000 a year. Assuming your salary rises, at what salary (hourly wage) would you begin to work fewer than 40 hours a week (remember, the job permits flexible hours)? If your rich aunt dies and leaves you $500,000, would this alter the wage rate at which you cut your work hours? Do you think this wage rate will be the same when you are 35 and have two children?

Each person will have a different wage where their supply of labor curve bends backward. Getting a large inheritance will generate substantial nonwage income and typically lead to fewer hours worked. Having a family will probably raise the income required before you will cut your hours.