Competitive Labor Demand

demand for labor Demand for labor is derived from the demand for the firm’s product and the productivity of labor.

The competitive firm’s demand for labor is derived from the demand for the firm’s product and the productive capabilities of a unit of labor.

Marginal Revenue Product

Assume that a firm wants to hire an additional worker, and that worker is able to produce 15 units of the firm’s product. Further, assume that the product sells for $10 a unit, and labor is the only input cost (such as blackberry picking in Oregon), with this cost including a normal return on the investment. The last worker hired is therefore worth $150 to the firm (15 × $10 = $150). If the cost of hiring this worker is $150 or less (remember, a normal profit is included in the wage), then the firm will hire this person. If the wage rate for labor exceeds $150, a competitive firm will not hire this marginal worker.

282

MRP differs from worker to worker. As we saw in Chapter 7, production is subject to diminishing marginal returns. In the example of blackberry picking, the first blackberry picker takes the nearest low-hanging fruit. The next picker takes low-hanging fruit farther away. The third has to do a little more work to harvest the same amount of fruit. Because each additional worker is able to pick less fruit per day, the MRP of each additional worker will correspondingly fall. This decrease in MRP represents the same diminishing marginal returns concept introduced in the product market.

marginal physical product of labor The additional output a firm receives from employing an added unit of labor (MPPL = ΔQ ÷ ΔL).

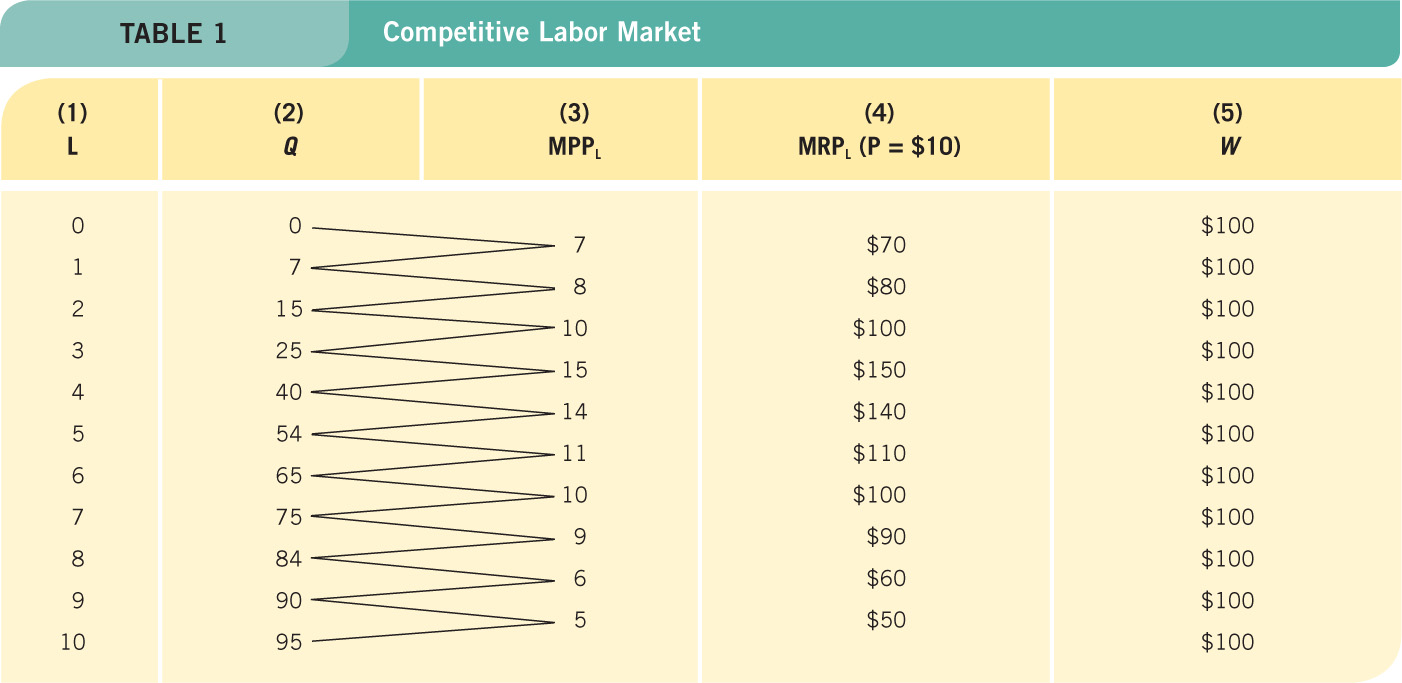

To see how this works in greater detail, look at Table 1. The production function here is similar to the one used earlier in the chapter on production. Column (1) is labor input (L), column (2) is total output (Q), and column (3) is the marginal physical product of labor (MPPL). This last value is the additional output a firm receives from employing an added unit of labor (MPPL = ΔQ ÷ ΔL). For example, adding a fourth worker raises output from 25 to 40 units, thus the marginal physical product of labor for this additional worker is 15 units.

marginal revenue product The value of another worker to the firm is equal to the marginal physical product of labor (MPPL) times marginal revenue (MR).

In this example, the firm is operating in a competitive market, therefore it can sell all the output it produces at the prevailing market price of $10. The value of another worker to the firm, called the marginal revenue product (MRPL), is equal to the marginal physical product of labor times marginal revenue:

MRPL = MPPL × MR

value of the marginal product The value of the marginal product of labor (VMPL) is equal to marginal physical product of labor times price, or MPPL × P.

In our example, adding a fourth worker leads to a marginal revenue product of $150; we multiply the marginal physical product of labor of 15 units by the marginal revenue—or price in this competitive market—of $10 per unit.

A related term to marginal revenue product is the value of the marginal product, defined as VMPL = MPPL × P. Because competitive firms are price takers for whom marginal revenue is equal to the price of the product (MR = P), VMPL = MRPL in the competitive case.

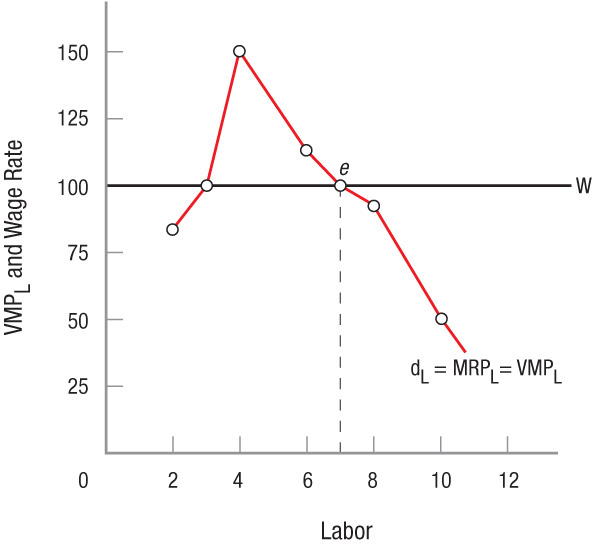

Column (4) contains the firm’s MRPL. Additional workers add this value to the firm. Thus, the marginal revenue product curve is the firm’s demand for labor, which is graphed in Figure 3. Note how the marginal revenue product reaches a maximum at 4 workers, as shown in column (4) of the table and in the figure.

FIGURE 3

The Competitive Firm’s Demand for Labor This figure reflects the data from columns (4) and (5) of Table 1. In this example, the firm is operating in a competitive market, therefore it can sell all the output it produces at the prevailing market price. The value of the additional worker to the firm, the marginal revenue product (MRPL), is equal to the marginal physical product of labor times marginal revenue (or price in this case). MRPL is the competitive firm’s demand for labor. If wages are equal to $100, the firm will hire 7 workers (point e).

283

Competitive firms hire labor from competitive labor markets. Because each firm is too small to affect the larger market, it can hire all the labor it wants at the market-determined wage.

Table 1 and Figure 3 assume that the going wage for labor (W) is $100. For our firm, this results in 7 workers being hired at $100 (point e), because this is the employment level at which W = MRPL. Note that W = MRPL at 3 workers as well, but because the marginal revenue product is greater than the wage rate for workers 4 to 6, the firm would hire 7 workers, not 3, to maximize its gains. The value to the firm of hiring the seventh worker is just equal to what the firm must pay this worker. Profits are maximized for the competitive firm when workers are hired out to the point at which MRPL = W.

However, if market wages were to fall to $90, the firm would hire an eighth worker to maximize profits, because with 8 employees, MRPL is also equal to $90.

In a competitive labor market, the prevailing wage ($90 in this case) would be paid to each worker regardless of the actual MRP. Thus, firms maximize gains from hiring workers in the labor market similar to how consumers maximize consumer surplus when buying goods and services in the product market.

Factors That Change Labor Demand

The demand for labor is derived from product demand and labor productivity—how much people will pay for the product and how much each unit of labor can produce. It follows that changes in labor demand can arise from changes in either product demand or labor productivity. Because most production also requires other inputs, changes in the price of these other inputs also change the demand for labor.

Changes in Product Demand A decline in the demand for a firm’s product will lead to lower market prices, reducing MRPL, and vice versa. As MRPL for all workers declines, labor demand will shift to the left. Anything that changes the price of the product in competitive markets will shift the firm’s demand for labor.

A recent trend in the movie industry is for people to download movies directly to their computers or to order movies directly from their televisions. This has decreased demand for movies on DVDs, and subsequently led to a reduction in prices. As a result, labor demand by DVD movie manufacturers has shifted to the left.

284

Changes in Productivity Changes in worker productivity (usually increases) can come about from improving technology or because a firm uses more capital or land along with its workforce. For example, some supermarkets have introduced digital price tags on their store shelves, allowing prices to be changed remotely instead of having a store clerk physically replace each tag on the shelf as prices change. Such improvements in productivity raise MPPL. The demand for the marginal worker rises, shifting the demand for labor to the right as firms are willing to pay higher wages. To be sure, the number of workers hired may fall due to digitalization, but the workers programming the price codes, as in any capital-intensive industry, are generally more highly skilled and hence earn higher wages.

Changes in the Prices of Other Inputs Changes in input prices can affect the demand for labor through their effect on capital prices. For example, rising steel and glass prices can dramatically raise the costs of equipment such that firms are unable to replace aging equipment. Without the ability to afford the rising costs of new capital equipment, firms are forced to substitute labor for capital in new projects, thus increasing the demand for labor. Relative costs of capital and labor will therefore affect the capital and labor mix firms choose for their production.

At this point, we know that more labor will be hired when wages fall, but how much more? The answer depends on the elasticity of demand for labor.

Elasticity of Demand for Labor

elasticity of demand for labor The percentage change in the quantity of labor demanded divided by the percentage change in the wage rate.

The elasticity of demand for labor (EL) is the percentage change in the quantity of labor demanded (QL) divided by the percentage change in the wage rate (W). This elasticity is found the same way we calculated the price elasticity of demand for products, except that we substitute the wage rate for the price of the product:

The elasticity of demand for labor measures how responsive the quantity of labor demanded is to changes in wages. An inelastic demand for labor is one in which the absolute value of the elasticity is less than 1. Conversely, an elastic curve’s computed elasticity is greater than 1.

The time firms have to adjust to changing wages will affect elasticity. In the short run, when labor is the only truly variable factor of production, elasticity of demand for labor is more inelastic. In the long run, when all production factors can be adjusted, elasticity of demand for labor tends to be more elastic.

Factors That Affect the Elasticity of Demand for Labor

Although time affects elasticity, three other factors also affect the elasticity of demand for labor: elasticity of product demand, ease of substituting other inputs, and labor’s share of the production costs. Let’s briefly consider each of these.

Elasticity of Demand for the Product The more price elastic the demand for a product, the greater the elasticity of demand for labor. Higher wages result in higher product prices, and the more easily consumers can substitute away from the firm’s product, the greater the number of workers who will become unemployed. An elastic demand for labor means that employment is more responsive to wage rates. The opposite is true for products with inelastic demands.

Ease of Input Substitutability The more difficult it is to substitute capital for labor, the more inelastic the demand for labor will be. At this point, computers cannot yet substitute for pilots in commercial airplanes, which results in an inelastic demand for pilots. As a result, pilots have been able to secure high wages from airlines. The easier it is to substitute capital for labor, the less bargaining power workers have, and labor demand tends to be more elastic.

285

Labor’s Share of Total Production Costs The share of total costs associated with labor is another factor determining the elasticity of demand for labor. If labor’s share of total costs is small, the demand for labor will tend to be rather inelastic. In the example of airline pilots, the percentage of costs going to pilot wages is small, perhaps 10%. Thus, a large increase in pilot wages would have a relatively small effect on ticket prices and demand, resulting in little change in demand for pilot labor. The opposite is true when labor’s share of costs is large.

Competitive Labor Market Equilibrium

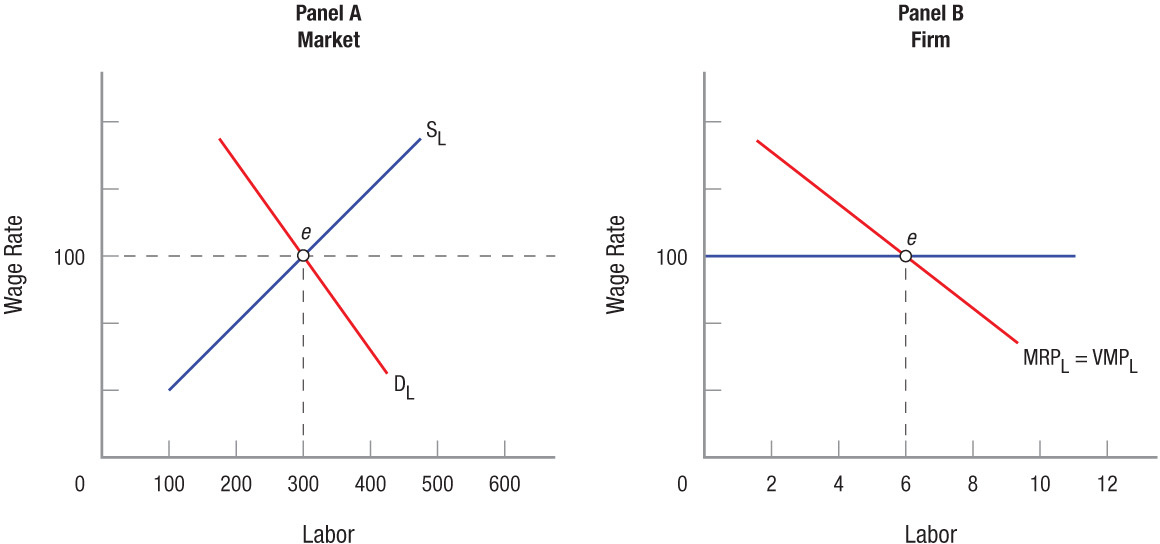

Generalized market equilibrium in competitive labor markets requires that we take into account the industry supply and demand for labor. The market supply for labor (SL) is the horizontal sum of the individual labor supply curves in the market.

The market demand for labor, however, is not simply a summation of the demand for labor by all the firms in the market. When wages fall, for instance, this affects all firms—all want to hire more labor and produce more output. This added production reduces market prices for their output and negatively affects the demand for labor. For our purposes it is enough to be aware that market demands for labor are not the horizontal summation of individual firm demands.

Turning to Figure 4, we have put both sides of the market together. In panel A, the competitive labor market determines equilibrium wage ($100 per day) and employment (300 workers) based on market supply and demand. Individual firms, in light of their own situation, hire 6 workers at the point where this equilibrium wage is equal to marginal revenue product (MRPL), point e in panel B. Much like the product markets we discussed in earlier chapters, the invisible hand of the marketplace sets wages and in the end determines employment.

FIGURE 4

Competitive Labor Markets In panel A, the competitive labor market determines equilibrium wages ($100 per day) and employment (300 workers). Individual firms hire 6 workers, where this equilibrium wage is equal to marginal revenue product (MRPL), point e in panel B.

To this point we have assumed that labor markets are competitive and that firms are able to hire as many workers as they desire at the prevailing wage rate. This analysis of competitive labor markets goes a long way but just as with product markets, it does not tell the whole story. We are going to look at two familiar cases in which the competitive model is clearly not the case. The first case is economic discrimination in the labor market in which the personal preferences of employers, employees, or consumers cause some workers to be preferred over others, creating wage differentials. The second case involves unions, which restrict labor supply in certain industries to raise wages relative to nonunion industries. When wage differentials exist for workers performing the same tasks, we say that labor markets are imperfect. There are other, more technical instances of imperfect labor markets—we hold these until the Appendix.

286

Reality TV and the Labor Market for Entertainers

Before the onslaught of reality shows that are today a ubiquitous presence on our television schedules, becoming a “TV star” was a much more arduous endeavor. One would need to find an agent and audition for specific roles, and then wait until a producer found an appropriate role for the aspiring actress or actor. The labor market for TV entertainment was considerably smaller at that time.

That all changed in 1992, when MTV debuted The Real World as an experiment bringing unknown people without any acting experience (but with unique personalities or traits) together to live in a house with cameras rolling. For the rest of the decade, The Real World continued to launch new seasons with new participants, but the idea of reality TV did not truly catch on until a major network, CBS, debuted Survivor, in 2000. Again produced as an experiment to fill a slow summer schedule, it became an instant hit.

Moreover, Survivor started a global phenomenon, which led to hundreds of reality shows including the top-rated series The Amazing Race, The Apprentice, and Big Brother, among others. Further, it led to the creation of new talent competitions including American Idol and America’s Got Talent, which again turned unknowns into stars, even if just for one season.

How does reality TV affect the labor market for TV entertainers? With reality TV, almost anyone can audition for a show, with the eventual “star” being determined as the shows progress in front of television audiences. As a result, the supply of labor in the entertainment labor market has increased as more people seek to become the newest star.

But perhaps a greater effect is the new demand for labor. Traditional programs such as situation comedies and soap operas require networks to secure long-term contracts with their casts to ensure they return each season. Because reality TV stars generally appear for just one season, producers are constantly looking to cast new people each season. Although the success of reality TV has perhaps reduced the demand for traditional acting roles, it has created huge labor demand (opportunities), and subsequently higher wages, to the benefit of many aspiring entertainers.

COMPETITIVE LABOR DEMAND

- The firm’s demand for labor is a derived demand—derived from consumer demand for the product and the productivity of labor.

- Marginal revenue product is equal to the marginal physical product of labor times marginal revenue.

- The demand for labor is equal to the marginal revenue product of labor for competitive firms.

- The demand for labor curve will change if there is a change in the demand for the product, if there is a change in labor productivity, or if there is a change in the price of other inputs.

- The elasticity of demand for labor is equal to the percentage change in quantity of labor demanded divided by the percentage change in the wage rate.

- The elasticity of demand for labor will be more elastic the greater the elasticity of demand for the product, the easier it is to substitute other factors for labor, and the larger the share of total production costs attributed to labor.

- Market equilibrium occurs at the point at which the labor demand and supply curves intersect.

287

QUESTION: Individuals are different in terms of ability, attitude, and willingness to work. Given this fact, does it make sense to assume labor is homogeneous? Does this model better fit firms such as Wal-Mart that hire 800+ employees at each store at roughly standardized wages than, say, firms such as Google, which look for highly skilled computer geeks?

For many jobs, firms have standardized procedures that each employee follows. Therefore, the difference in productivity between individuals is relatively narrow. While homogeneous labor is a simplification, taking in everyone’s difference would make analysis impractical. No, the model explains both since markets exist for each broad category of workers.