Labor Unions and Collective Bargaining

Suppose Max, an engineer and project coordinator, has worked at a large construction company for eight years. He had been training new employees on various aspects of cost estimating and job specification, and he noticed that these new people were being hired at salaries approaching his own. He requested a raise several times, but was essentially ignored. Exasperated, he refused to go to work one day, informing his boss that he would not return without a raise. He did not quit; he simply staged a walkout and refused to return until given a raise. In other words, Max staged a one-man strike. He was out for two weeks before his supervisor called and asked him how much he wanted. They settled on a raise of over 20%.

This story is unique in that one-person strikes are rarely successful; more often they are career busters. In most instances, individual employees have little control over wages or job conditions, essentially being at the mercy of employers and the market. This is the primary reason that unions exist: Collective action is more powerful than the action of one individual. As individuals, we can easily be replaced (except in rare occasions like for Max in the story above). To replace an entire workforce, on the other hand, imposes serious costs to an employer.

This section looks at the role unions play in our economy, their history, and their effects on the labor market. We show how unions create wage differentials that work against the assumptions of the competitive labor market in which all workers earn the same wage. We will see that although unions have been successful in some industries, their influence has faded in other industries.

Types of Unions

Labor unions are legal associations of employees that bargain with employers over terms and conditions of work, including wages, benefits, and working conditions. They use strikes and threats of strikes, as well as other tactics, to try to achieve their goals.

Unions are usually defined by industry, or by craft or occupation. A craft union represents members of a specific craft or occupation, such as air traffic controllers (PATCO), truck drivers (Teamsters), and teachers (AFT). An industrial union represents all workers employed in a specific industry. Examples include auto workers (UAW) and public employees (AFSCME).

Benefits and Costs of Union Membership

Without a union, each individual employee would have to bargain with management over his or her own wages, benefits, and working conditions. Unions bring collective power to this bargaining arrangement. The source of this power is ultimately the willingness of the union to strike if no agreement is reached during negotiations. Collective bargaining often leads to a more equitable pay schedule than individual negotiation. It also provides workers with greater job security by protecting them against arbitrary or vindictive decisions by management.

Union membership, like everything else, has its price. First, union members must pay monthly dues. Then, if negotiations break down and a strike is called, wages are lost and the possibility exists, however remote, that management will refuse to settle with the union and replace the entire workforce. Finally, union workers must give up some individual flexibility because their work rules are more rigid.

293

Brief History of American Unionism

Labor unions date from the late 18th century in England. In the United States, public attitudes toward unions were highly unfavorable until the Great Depression. In the early part of the 20th century, employers could easily secure legal injunctions against union organization by arguing that unions behaved like monopolies, in violation of antitrust laws. Employers often required employees to sign enforceable yellow dog contracts, in which they agreed not to join a union as a condition of employment.

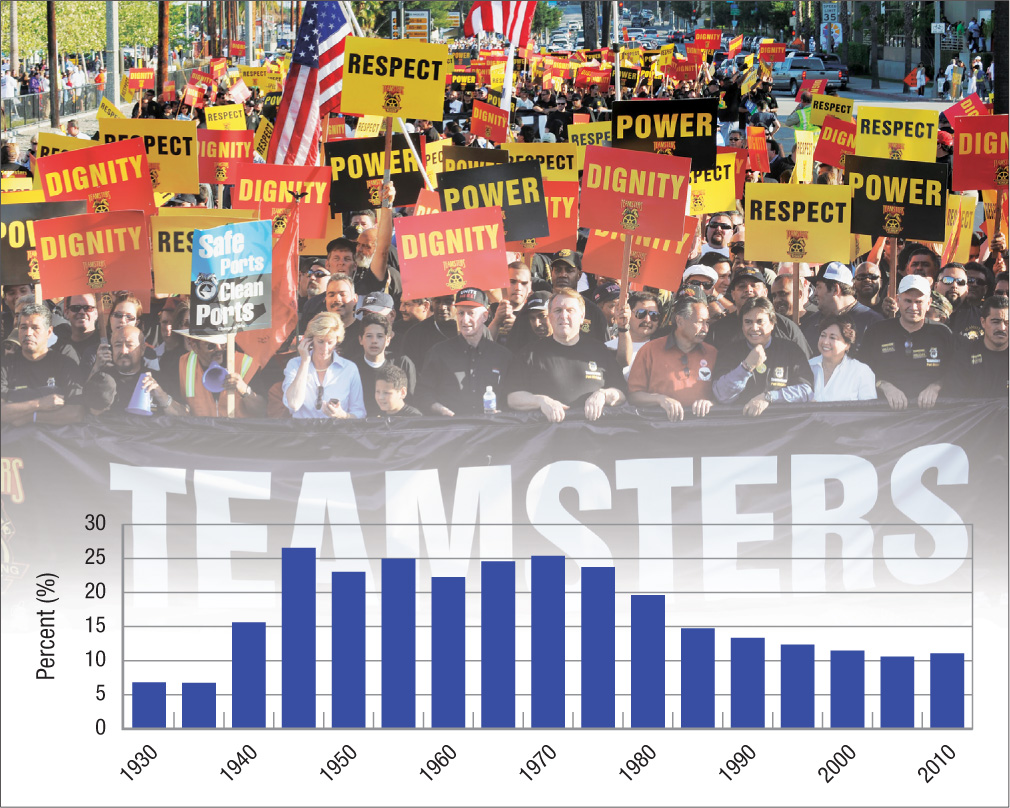

Figure 6 shows union membership as a percentage of total employment since 1930. Going into the 1930s, unions represented just over 7% of workers because of public attitudes and legal restrictions. With the onset of the Depression, attitudes about collective bargaining began to change. In 1932, Congress passed the Norris—LaGuardia Act, which outlawed yellow dog contracts and prohibited injunctions against union organizing. Then, in 1935, Congress enacted the Wagner Act, or the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). It prohibited a variety of unfair labor practices by employers, including firing employees for engaging in union activities. The act also required employers to “bargain in good faith” with those unions that had won recognition through a majority vote of the firm’s workers.

FIGURE 6

Union Membership as a Percent of Employment Union membership grew dramatically from the mid-1930s until after World War II. Following the war, over one-quarter of American workers were unionized. Union membership has fallen because benefits obtained by unions for union members spread throughout the wider workforce, making the benefits of joining a union less valuable. Also, the changing economy led to faster growth in the service sector, which has traditionally been less unionized.

The NLRA also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to oversee union certification elections. These elections were to be held to determine which union, if any, would represent employees.

As Figure 6 illustrates, union membership grew dramatically from the mid-1930s until after World War II. Following the war, union membership covered over one-quarter of American workers. It was concentrated in a few major industries.

294

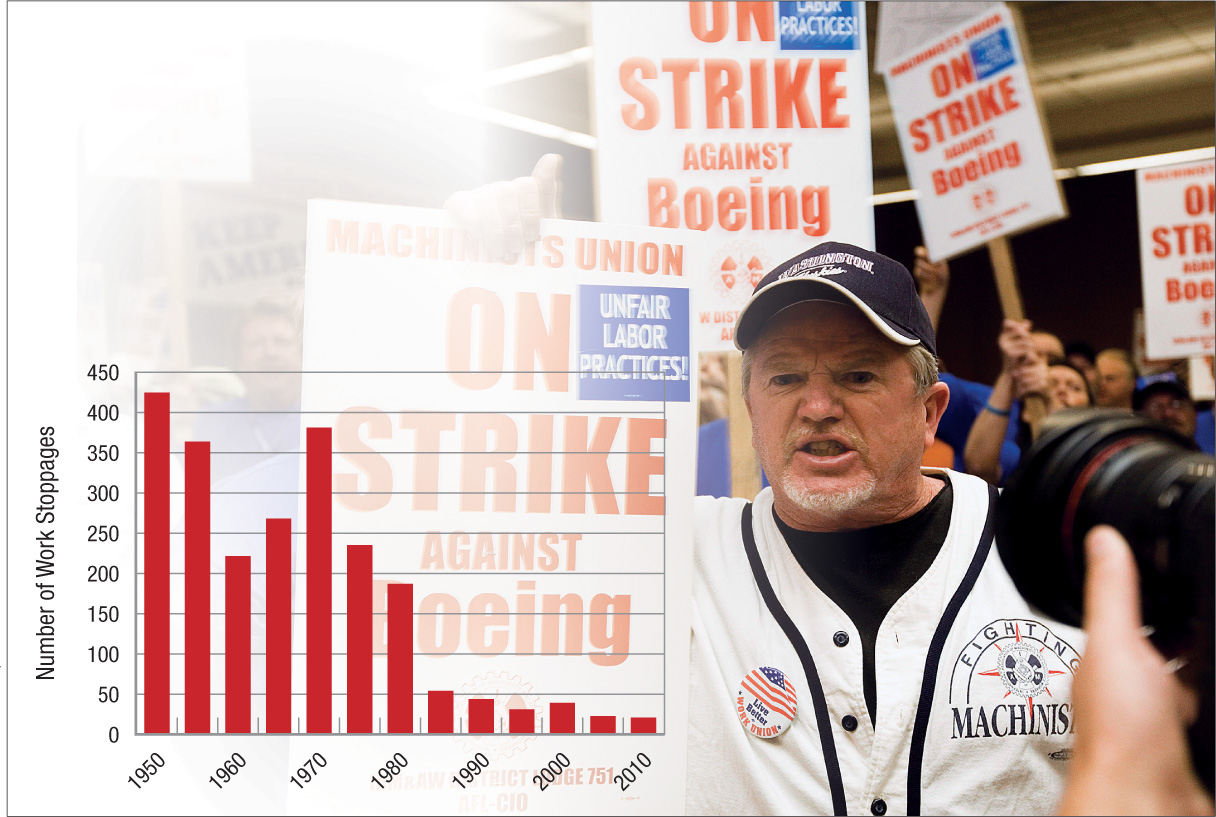

Figure 7 shows work stoppages, or strikes, since 1950. In 1946 a rash of strikes turned public opinion against the unions; many people felt unions had become too powerful. Because of this swing in popular opinion, in 1947 Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which prohibits some unfair labor practices by unions. Unions could no longer coerce or discriminate against workers who chose not to join the union, and unions were required to bargain in good faith, just like employers. With the passage of this act, the prolabor aspects of the 1935 Wagner Act were balanced.

FIGURE 7

Work Stoppages (Strikes) This figure shows work stoppages, or strikes, since 1950. In 1946, numerous strikes turned public opinion against unions. In 1947, Congress reacted by passing the Taft-Hartley Act, seeking a balance between unions and management. After this, the use of work stoppages by unions gradually began to decline.

closed shop Workers must belong to the union before they can be hired.

union shop Nonunion hires must join the union within a specified period of time.

agency shop Employees are not required to join the union, but must pay dues to compensate the union for its services.

right-to-work laws Laws created by the Taft-Hartley Act that permitted states to outlaw union shops.

Taft-Hartley changed the collective bargaining landscape dramatically by ending closed shops, workplaces in which workers are required to be union members before they can be hired. A union shop is one in which nonunion hires must join the union within a specified period, usually 30 days. In an agency shop, employees are not required to join the union, but they must pay union dues to compensate the union for its services. The Taft-Hartley Act outlawed closed shops outright, while permitting states to pass right-to-work statutes that prohibit union shops. Today, at least 24 states have right-to-work laws.

Until 1962, all collective bargaining statutes focused on the private sector; public employees were prohibited from organizing. In 1962, however, President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10988, giving federal workers the right to bargain collectively. Still, public employees are not permitted to strike. Rather, when an impasse is reached, both sides must submit to binding arbitration in which a neutral arbitrator resolves the dispute. In 2011, the collective bargaining rights of public employees came to the forefront of public debate as many state legislatures considered bills to reverse these rights. This is discussed further in the Issue box.

295

Why has union membership declined as a percentage of wage and salary workers since World War II? The answer lies partly in the changes in labor laws just discussed, the country’s changing economy—notably, a larger service sector—and ironically, the very success of labor at pushing its agenda of promoting rules that protect workers (such as minimum wage laws, antidiscrimination statues, and restrictions on firing employees) through Congress and the courts has resulted in union membership being a little less valuable. As a result, union membership may continue to shrink as a percentage of the workforce.

Union Versus Nonunion Wage Differentials

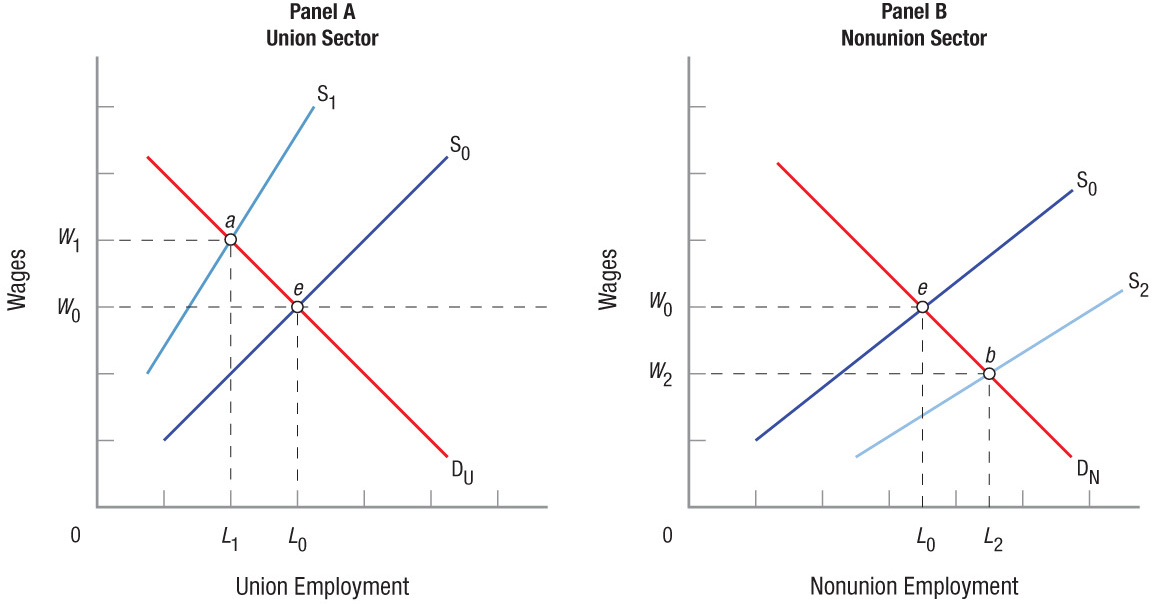

Why join a union? The primary benefit to unionization should be higher wages, given the union’s collective bargaining power. The general theoretical argument for union—nonunion wage differentials is illustrated in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8

Union Versus Nonunion Wage Differentials This figure illustrates the analysis of union—nonunion wage differentials. Unions increase wages in their sectors by restricting entry into union jobs. Assuming the markets for unionized and nonunionized jobs begin at equilibrium, at point e in both panels, union and nonunion wages are initially W0. If the union successfully restricts supply to S1 in panel A, union wages will rise to W1, but employment will fall to L1 (point a). Those workers released will have no choice but to move to the nonunion sector represented in panel B, thus increasing its supply to S2. Equilibrium in the nonunion sector thus moves to point b, where more workers (L2) are employed at a lower wage (W2). The result is a wage differential equal to W1 − W2.

This figure shows how unions are able to increase the wages in their sectors by restricting entry into union jobs. The markets for both unionized and nonunion labor begin at equilibrium, at point e in both panels of Figure 8. Thus, union and nonunion wages are initially equal, at W0. If the union successfully restricts supply to S1 in panel A, union wages will rise to W1, but employment will fall to L1 (point a). Those workers who are released have no choice but to move over to the nonunion sector represented in panel B, thus shifting its supply to S2. Equilibrium in the nonunion sector moves to point b, where more workers (L2) are employed at lower wages (W2). The resulting wage differential, W1 − W2, is caused by successful collective bargaining in the union sector. Notice that this analysis is substantially the same as that for discrimination in the segmented labor force described in Figure 5 earlier.

Union—nonunion wage differentials vary by the union, occupation, industry, and historical period. In general, average union wages are 10% to 20% higher than the average nonunion wage. Union wage effects are most pronounced among blue-collar workers and service employees. These differentials suggest that unionization may tend to reduce the inequities inherent in labor markets.

296

Will Public Unions Become an Endangered Species?

“I love teachers—I just can’t stand your union.”

—New Jersey Governor Chris Christie (Feb. 24, 2011, New York Times Magazine)

For nearly a month in February 2011, thousands of union workers staged a round-the-clock protest at the Wisconsin state capital as state legislators debated whether to prohibit collective bargaining among state employees including teachers, state agency employees, and others (though policemen and firemen were exempt from this legislation). The act effectively ended the long-standing ability of state workers to form unions within their professions.

As the quote from New Jersey Governor Christie suggests, Wisconsin was hardly alone. Attempts by other states to eliminate collective bargaining for public unions or otherwise reduce their powers subsequently arose. For example, Ohio passed a law abolishing collective bargaining for public unions; however, unlike Wisconsin, voters successfully overturned the law at the ballot box.

Still, why has there been hostility toward public unions? There is a simple answer: Public unions have an important difference from private unions such as the automobile workers union or the steelworkers union.

Collective bargaining between private unions and private firms rests on three things. First, unions have the ability to strike. Second, while this threat of a strike can bring management to the negotiating table, management is constrained in what it can offer because of the need for the firm to generate profits. Third, the ultimate arbiter of what can be asked for by unions and acceded to by management is the market: The firm has to stay in business.

What is different about public unions? Many public unions are legally prevented from striking (teachers’ unions are often an exception to this)—but this should make public unions more acceptable to state government, not less.

Public unions have a potent weapon that private unions do not have: the ballot box. Public unions can threaten state officeholders with something private unions cannot: votes, and getting out the votes to remove people from office. State officeholders have an incentive to placate large public unions if they want to keep their jobs.

Critics of public unions say the result of this political power has been higher wages and benefits unseen in the private sector. For example, private businesses generally make workers contribute toward their health insurance premiums. Public union workers often do not have to make such contributions.

Who pays for these public union benefits? The taxpayers. What became particularly galling to harried taxpayers who had suffered through their own wage freezes or wage rollbacks were public unions that demanded large pay raises even during the depths of the last recession. Rather than just say no, politicians in some states sought more radical solutions such as abolishing collective bargaining for public unions.

LABOR UNIONS AND COLLECTIVE BARGAINING

- Unions are typically organized around a craft or an industry.

- Unions and the managers of firms must bargain “in good faith.”

- In a closed shop, only union members are hired. This was outlawed by the Taft-Hartley Act. In a union shop, nonunion workers can be hired, but they must join the union within a specified period. An agency shop permits both union and nonunion workers, but the nonunion workers must pay union dues.

- Union wage differentials are between 10% and 20% higher.

QUESTION: Union negotiations always seem to run up against a “strike deadline.” Are there incentives for both sides to put off a settlement until the very last moment?

Both sides work hard to get the best bargain for their constituents. There are incentives to continue negotiations up to the last moment to get the most and to appear to be driving a hard bargain. Strikes involve costs, and both sides use the threat of imposing these costs as a bargaining chip.

297