Putting It All Together: An Analysis of Climate Change

Throughout this chapter, we saw how the market failures of externalities, public goods, and common property resources create markets that make it difficult to achieve a socially efficient outcome without some sort of intervention. As a result, governments often are tasked with establishing policies that attempt to incentivize individuals and firms to take actions that lead to a more efficient outcome. But how are such policies established? And how are the effects measured?

Many questions arise that require adequate measurement of how individuals value various objectives. For example, how do we account for the value of biodiversity? How much would we pay to keep certain species from going extinct? Or how much benefit must we obtain to endure living in a polluted city? The answers to these and other questions require the use of a consistent technique to ensure policies are well established to promote social efficiency.

cost-benefit analysis A methodology for decision making that looks at the discounted value of the costs and benefits of a given project.

A common approach taken to develop and debate policies is to use some form of cost-benefit analysis. Cost-benefit analysis provides a rational model for policy decisions, forces a focus on alternatives (opportunity costs), draws conclusions about the optimal scale of projects, makes the intergenerational aspects explicit through discounting, and takes into account the explicit preferences of individuals. In short, it takes all of the future benefits and costs of a proposed policy and discounts them to the present to determine whether it is worth implementing.

One of the major difficulties with cost-benefit analysis for big public projects and environmental programs is measuring nonmarket or intangible aspects of projects. To resolve these issues, economists use various methods to approximate the values of intangible items, such as how much people pay to avert harm, or even direct surveys among a small but representative portion of the population to determine how individuals value certain aspects of the environment.

Cost-benefit analysis, then, is a rational approach to valuing some things that are hard to put a price on. The issue of climate change is one topic that involves many such variables. Let’s analyze in greater detail the issue of global warming, which often is characterized as the mother of all market failures.

355

Understanding Climate Change

There is growing scientific consensus that without a significant reduction in emissions, global warming from the buildup of greenhouse gases is likely to lead to irreversible damage to the climate, ecosystems, and coastlines.

A sense of urgency surrounds climate change because the state of climate science has advanced to the point where scientists can now put probability estimates on certain impacts of warming, some of which are catastrophic. Current levels of greenhouse gases are roughly 403 parts per million (ppm).5 This compares to 280 ppm before the Industrial Revolution. Scientists predict that if greenhouse gases exceed 450 ppm, average global temperatures will have risen 2 degrees Celsius since the Industrial Revolution, a change that would lead to dramatic consequences. If the current trend continues, the 450 ppm threshold will be exceeded in less than 25 years.

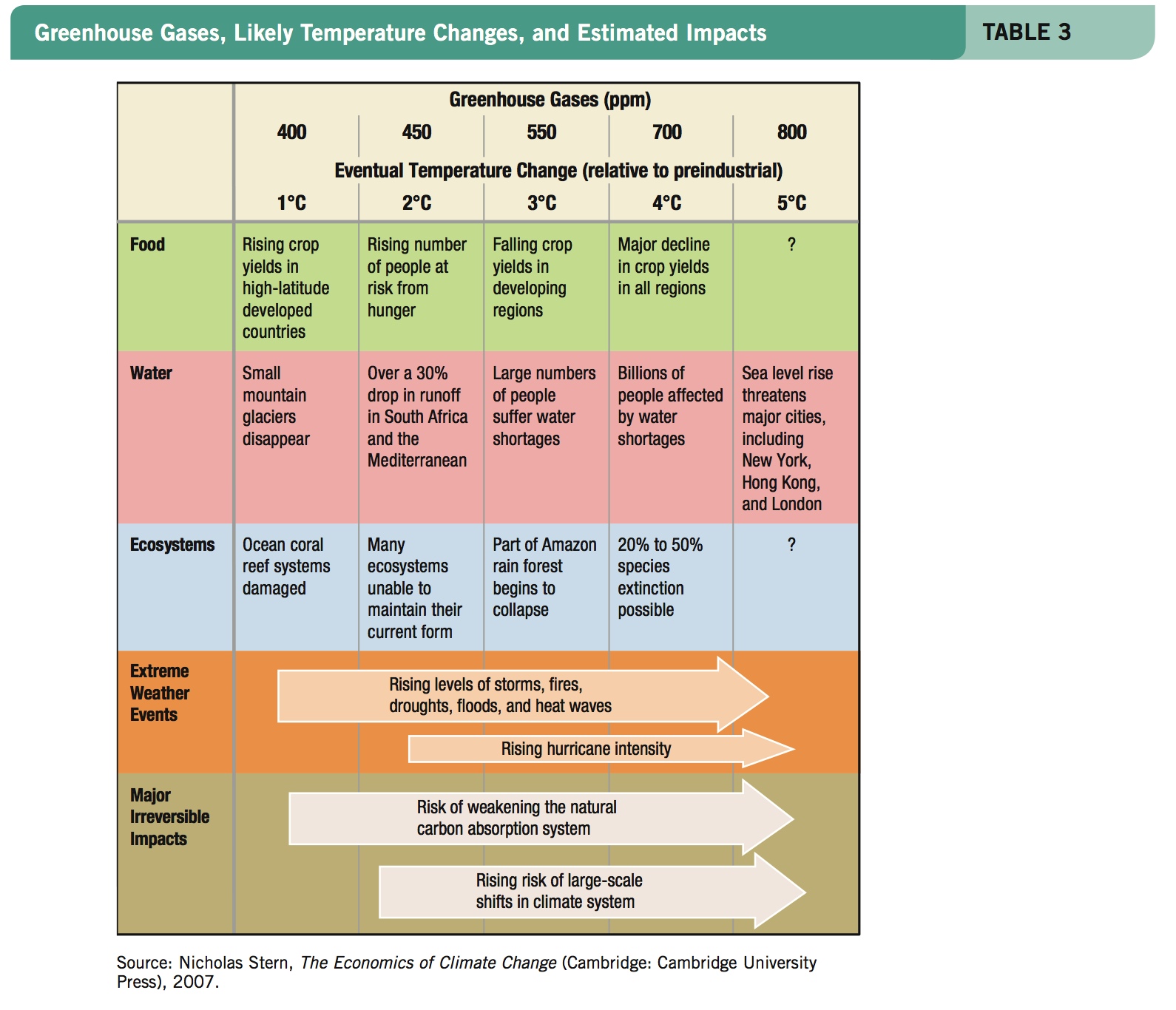

What will happen as greenhouse gases increase and lead to global warming? Table 3 estimates these effects. The top part of the table shows a range of greenhouse gases from 400 ppm to 800 ppm, with predicted effects on temperature below it. The bottom part estimates the impacts likely to arise with each increase in temperature. The estimated effects of a difference of just 1 or 2 degrees raise serious concerns.

356

Unique Timing Aspects

The global environment is essentially a common resource with many public goods aspects, and climate change is a huge global negative externality. But what makes analysis and decision making so difficult is the long time horizon that must be considered. Most cost-benefit studies do not look out 50 to 100 years and beyond. This extended time horizon adds a host of difficulties and uncertainties.

Air or water pollution is something that we can see on the horizon, can be measured, is typically localized, and can be altered in a short period of time by some of the approaches discussed earlier. Global warming, in contrast, is not something we can generally see; it is cumulative (this year’s CO2 adds to that from the past to raise concentrations in the future); and once it reaches a certain level, it may lead to extreme consequences that cannot be reversed.

Cleaning up pollution problems typically involves finding that level of abatement at which the marginal costs of abatement equal the marginal benefits from abatement and either taxing, assigning (or auctioning) marketable permits, or using command and control policies to require the optimal level of abatement. However, reducing global warming gases is not a short-term objective, but a cumulative process across many years. Yet, our short-run decisions will have immense impacts in the long run. Small changes in emissions today may have little effect on the current generation, but will have sizable effects many decades out. This aspect of the problem seriously complicates any policymaking and economic analysis.

Public Good Aspects

To compound the problem further, global climate change is a public good. Greenhouse gas emissions “are the purest example of a negative public good; nobody can have less of them because someone else has more; and nobody can be excluded from their malign consequences or the efforts of others to ameliorate them.”6

One of the solutions is technical innovation that reduces our output of CO2. But knowledge and technology have large public good aspects, therefore private firms will find it difficult to collect the full returns on their innovation investments that reduce greenhouse gases. Other firms and countries will to some extent be free riders on private innovation, thus society (and the world) may get less than the socially optimal level of innovation. This will mean that a substantial amount of climate change research and development will have to be financed by governments.

Equity Aspects

Why should I do anything for posterity? What has posterity ever done for me?

GROUCHO MARX

Much of what we do today to reduce global warming will have little immediate impact on our lives. The impacts will show up in the latter half of the century. Any action taken today principally benefits our great-grandchildren. Groucho Marx’s joke not withstanding, this fact makes it more difficult to get a political consensus to act.

Also, rich countries will have to make the biggest sacrifices, yet they will not get the biggest benefits from efforts to reduce the impacts of global warming. Suppose that the United States reduces its dependence on carbon. What about China and India? They may decide that growth is worth more than a cleaner environment. At that point, the United States would have to be willing to pay China and India large sums to get them to decarbonize their economies. How well will that sell to American voters? Probably not well, but it may be what is ultimately necessary.

357

People in countries both rich and poor living along bodies of water will face floods if current climate forecasts come to pass. However, developing countries which are home to some of the world’s poorest people will face the greatest challenge adapting to flooding given their severely limited resources. In addition, developing nations rely heavily on agriculture, one industry that will be hardest hit by the warming of the Earth.

NOBEL PRIZE ELINOR OSTROM (1933-2012)

When economists talk about common property resources, they typically discuss the tragedy of the commons and suggest a solution that involves privatization or central government takeover and management of the resource. Elinor Ostrom was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for challenging this conventional wisdom by showing how user-managed resources, where people cooperate to solve a resource issue, can be effective.

Born in 1933 during the depths of the Great Depression and completing her doctorate in political science in 1965, her dissertation looked at a case in which saltwater was seeping into western Los Angeles’s water basin. A group of individuals formed a water association to solve the problem by creating rules and injected water along the coast. Their efforts saved the basin. This experience led her to look at other common resource problems from a new perspective.

She used field studies and thousands of case studies by other social scientists along with game theory to determine how these informal organizations evolved and what conditions make them successful.

Her work has determined the requirements for sustainable user-managed common resource property, including (a) rules must clearly define entitlement to the resource, (b) adequate conflict resolution measures must exist, (c) an individual’s duty to maintain the resource must be in proportion to his or her benefits, (d) monitoring and sanctioning must be by users or accountable to users, (e) sanctions should be graduated—mild for a first violation and stricter as violations are repeated, (f) governance and decision processes must be democratic, and (g) self-organization is recognized by outside authorities. When these institutional conditions are met, user management of common pool resources typically is successful.

Professor Ostrom’s insights and research have opened up an alternative to prevent the tragedy of the commons. Her work will be particularly important as nations begin working together to reduce the potential harm from global climate change, maybe our biggest common resource problem to date.

Finding a Solution

Climate change is global, therefore it will take concerted international effort and cooperation to create price signals and markets for carbon, and to develop and promote new technologies, especially in developing countries.

Many economists argue that using fewer fossil fuels today will result in lower spending on environmental protection in the future, like a form of insurance to reduce future harm on the environment. This will require a transition to a low-carbon economy that will require actions such as establishing a worldwide price for carbon that includes its external costs. This can be done using carbon taxes or tradable permits. Initiatives such as the European Union Emissions Trade System (EU ETS), launched in 2005, have taken first steps toward capping emissions levels using tradable permits.

Robert Socolow of Princeton University has suggested that much of the technology needed to reduce our carbon footprint is available today.7 He and several colleagues suggest that carbon emissions can remain constant over the next 50 years if the following techniques are implemented:

- Use more efficient vehicles and reduce vehicle use in general.

- Build more efficient buildings.

- Capture CO2 at power plants.

- Use nuclear power.

- Exchange biomass fuels for fossil fuels.

- Use wind and solar power.

- Reduce deforestation.

358

Clearly, undertaking some policies to reduce our carbon footprint as a nation represents an insurance policy on the future. As new climate change information becomes available, policies can be adjusted to reduce the potential costs in the future.

To that end, carbon dioxide emissions are frequently placed on political agendas. However, a slow economic recovery makes it harder to focus people’s attention on this issue. Furthermore, questions arise about the initial grant of permits in any cap-and-trade program. Do large established companies with huge capital resources get permits? What about smaller, possibly more innovative alternative energy companies? Do permits get auctioned off, and does this then favor the richer, more established companies? Political issues combine with economic issues to make this a thorny problem for the future.

As with climate change, each of the examples described in this chapter dealt with market failure in which externalities, public goods, or shared resources lead the market away from the socially desirable output. Resolving a market failure generally requires some policy tool, such as the assignment of property rights, regulation, or the creation of market incentives to achieve the ideal outcome. However, determining which policy tool to use often leads to intense debate, making issues of market failure a challenge that societies and their policymakers will continue to face.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: AN ANALYSIS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

- Global climate change is a huge negative externality with an extremely long time horizon.

- The public goods aspects of climate change make it a truly global problem.

- Balancing the current generation’s costs and benefits against the potential harm to future generations raises difficult economic issues.

- Actions taken today to reduce a potential future calamity are a form of insurance.

QUESTION: One of the most difficult aspects of climate change policy is determining how much individuals are willing to sacrifice today for a better environment in the future. What are some factors that may influence whether a person holds a high or low discount rate on the future with regard to environmental policy?

Many answers are valid. But any factor that causes one to place greater emphasis on the future would result in a lower discount rate. Such factors might include having children or grandchildren, a greater desire to preserve Earth’s natural beauty, having higher income or a business that relies on the availability of natural resources, or having empathy for future residents. Factors that might result in a high discount rate may include poverty, where emphasis is on improving one’s current economic well-being in the future, or other difficult situations (wars and civil strife) that focus more attention on the present than on the future.

359