Demand Curve for a Network Good

network demand curve A demand curve for a good or service that experiences a network effect, causing it to slope upward at lower quantities before sloping downward once the market matures.

Because the value of network goods is influenced by external benefits, a demand curve for a network good does not look like a typical downward-sloping demand curve. A network demand curve reflects the fact that the value of the good initially rises as more people purchase or subscribe to the good, which means that the demand curve has an upward-sloping portion at lower quantities. A general model of demand for network goods is described next.1

Demand for a Fixed Capacity Network Good

The model for a network demand curve makes two important assumptions. First, the model assumes that the short-run supply curve is limited to the capacity of the firm’s fixed investment, and therefore is vertical. For example, a new entrant in the airline industry starts off with just a few planes, and therefore the number of customers it can serve is fixed until it expands by purchasing more planes. Further, an airline must expand in large increments (that is, it must buy a new airplane that can serve hundreds of passengers a day), rather than by small increments, such as when a baker decides whether to make one more cake. Second, the model assumes that there is a short-run demand curve corresponding to each vertical supply curve that reflects the higher value of a larger network due to network externalities. These assumptions make the analysis easier but do not change the conclusions.

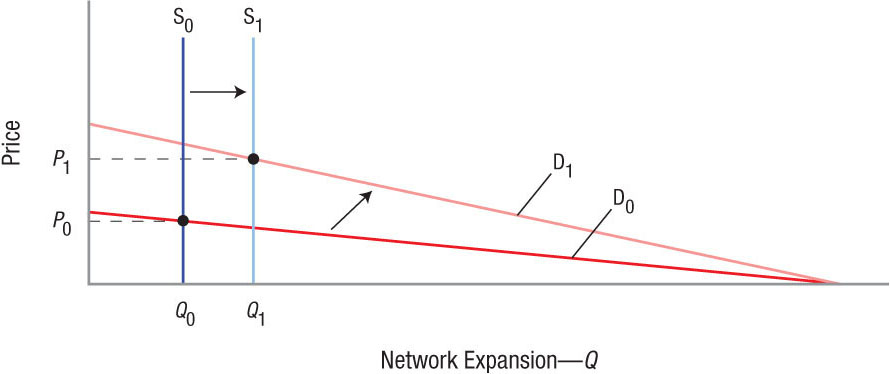

Figure 2 shows how a network market demand curve is developed. We start with a small network with a capacity of Q0, where demand is small and price (P0) is determined by the intersection of a vertical supply curve S0 at Q0 and demand D0 for that capacity. As the network expands (supply shift s to the right by an increment to S1), demand increases because the value to existing and new users increases. This is shown by the demand curve pivoting higher to D1 (while intersecting the horizontal axis at the same point as D0 to indicate a maximum demand for the network good) and reflecting a higher value to initial users and a higher market price at P1. This differs from a market for a nonnetwork good, in which an increase in supply would not result in an increase in demand. For a nonnetwork good, the increase in supply would lead to a lower price on the demand curve.

FIGURE 2

A Small Network with Fixed Capacity A small network has a fixed capacity of Q0, resulting in a vertical supply curve, S0. The intersection of S0 and D0 results in an equilibrium price of P0. As the network expands to S1, the value to existing and new users increases due to network effects causing the demand curve to pivot to D1. The intersection of S1 and D1 leads to a higher equilibrium price of P1. This differs from a market for a nonnetwork good, in which an increase in supply leads to a lower price.

371

Deriving the Full Network Demand Curve

Network effects are strongest in the early stages of a network good’s development, as each additional consumer increases the marginal benefit to all consumers of the good. However, this network effect is always opposed by the law of demand we learned in Chapter 3: As price rises, quantity demanded falls. Which effect predominates?

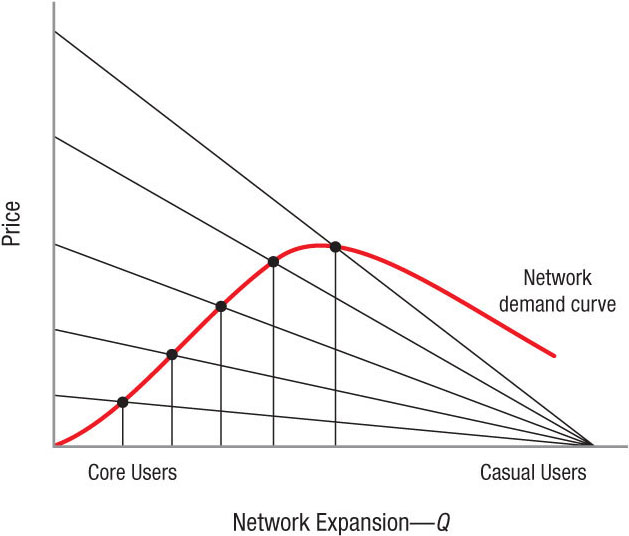

When the quantity of a good provided on the market increases (without any change in demand), the price must fall in order for the market to clear. But the existence of network externalities causes demand to increase when a network expands, allowing prices to rise. Because the price effect and the network effect work in opposition to one another, the market price for a network good depends on which effect is stronger. For most network goods, the network effect dominates the price effect for small quantities, resulting in an upward-sloping portion of the network demand curve, as shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

A Network Market Demand Curve Network goods initially have an upward-sloping demand curve as core users build the network by attracting others to buy the good. Once the market matures, a network demand curve becomes downward-sloping as casual users buy the good when the price drops.

core user A consumer who has a very high willingness to pay for a new product or service and is among the first to purchase it.

casual user A consumer who purchases a good only after the good has matured in the market and is more sensitive to price.

As the network expands along the upward-sloping portion of the network demand curve, the price increases as more core users—those who benefit most from consuming the good—purchase the good. The demand curve slopes upward as the network effect (which shift s demand to the right as quantity increases, increasing the price) dominates the price effect of an increase in quantity (which reduces the price).

As the market for a network good grows and reaches a critical number of consumers to support the network, additional consumers add fewer external benefits due to diminishing returns. These consumers who purchase the network good after it matures are called casual users (think of your grandmother buying an iPad only after everyone else in the family has one). Once a network good reaches this stage, the network demand curve slopes downward as the price effect (from the increase in supply due to lower production costs) dominates the network effect.

By connecting all of the intersections of demand and supply, a network demand curve is generated, which slopes upward from the origin as core users increase the value of the good and then slopes downward once the product matures and casual users buy the good.

372

Examples of Network Demand Curve Pricing in Our Daily Lives

What does the presence of a network demand curve mean for prices? It suggests that as a new network good is introduced, the price is kept low to attract new users. As the number of users increases, prices rise because people are willing to pay more for a network good used by more people. Prices continue to rise until the good matures, at which point prices must fall in order to sell a greater quantity.

Consider the following example: When Google launched in 1998, the search engine results displayed were quite bare—no ads, no preferred listings; the cost to use Google was essentially zero. However, as the number of users increased, Google began “charging” people to use the service by placing ads and suggested links alongside the search results. Although not a monetary cost, users pay an opportunity cost when viewing ads.

Another example of network demand curve pricing is a new rock band attempting to gain recognition by initially playing for nothing at local clubs, and/or offering their music free online. Once the band becomes better known, it begins charging for shows and for music downloads. Eventually, a downward-sloping demand curve will return, in which case lower prices are needed to increase quantity demanded. A similar effect can occur when an established musical artist prepares to release a new album. These examples demonstrate the upward- and downward-sloping nature of network demand curves.

DEMAND CURVE FOR A NETWORK GOOD

- The production of network goods is typically carried out in large increments due to high fixed capital costs.

- The short-run equilibrium for a network good occurs at the intersection of a fixed capacity vertical supply curve and the demand curve for that quantity.

- As a network expands, the effect of network externalities is reduced due to diminishing returns as the price effect becomes stronger.

- A network demand curve is upward sloping for smaller quantities (when network effects are strong) and downward sloping for larger quantities (when the network good matures and network effects weaken).

- A network demand curve reflects the role that core users (represented on the upward-sloping portion of the curve) have in building the value of the network.

QUESTION: Why does a network demand curve slope upward for small quantities of a good, then slope downward for higher quantities?

A network demand curve gains value based on the number of people who use it. For example, a network good with one consumer is virtually worthless. As more consumers buy the network good, its value rises and the network good becomes attractive to even more consumers. Once a good matures, the network effect weakens and additional consumers will buy the good only after the price drops. Hence, the demand curve slopes downward for higher quantities of the good.