What Is Economics About?

economics The study of how individuals, firms, and society make decisions to allocate limited resources to many competing wants.

scarcity Our unlimited wants clash with limited resources, leading to scarcity. Everyone (rich and poor) faces scarcity because, at a minimum, our time on earth is limited. Economics focuses on the allocation of scarce resources to satisfy unlimited wants.

Economics is a very broad subject. It often seems that economics has something important to say about almost everything.

To boil it down to a simple definition, economics is about making choices. Economics studies how individuals, firms, and societies make decisions to maximize their well-being given limitations. In other words, economics attempts to address the problem of having too many wants but too few resources to achieve them all, an important concept called scarcity. Note that scarcity is not the same thing as something being scarce. Although all resources are scarce, certain goods are less scarce than others. For example, cars are not very scarce—there are car dealerships around the country chockfull of cars ready to be sold, but that doesn’t mean you can go out tonight and buy three. Scarcity refers to the fact that one must make choices given the resource limitations she or he faces.

3

Economic Issues Are All Around Us

Economics is one of the most popular college majors in the country. This is because so much of what we do, the decisions we face, and the issues we confront involve economics.

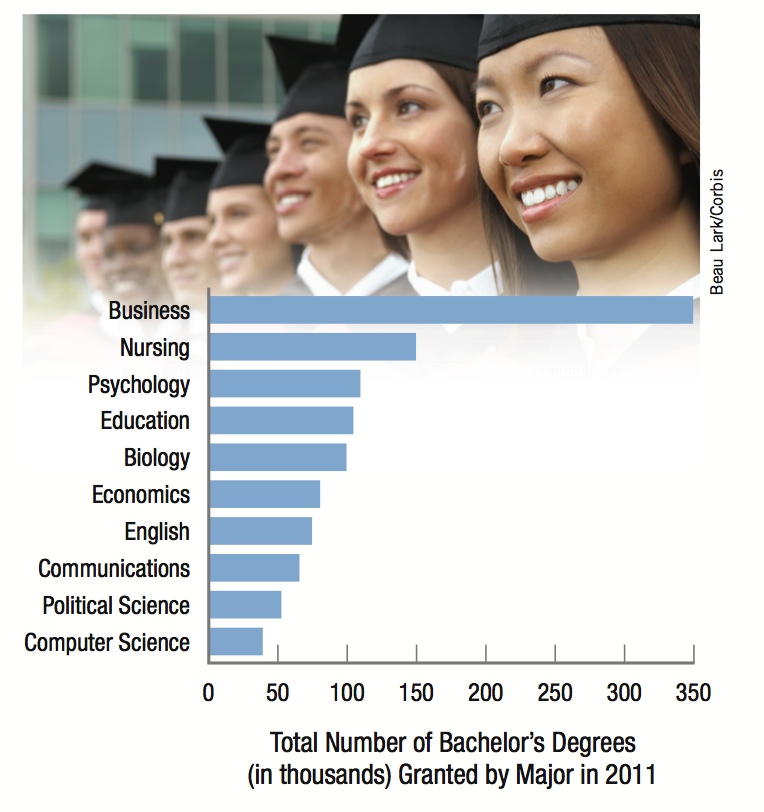

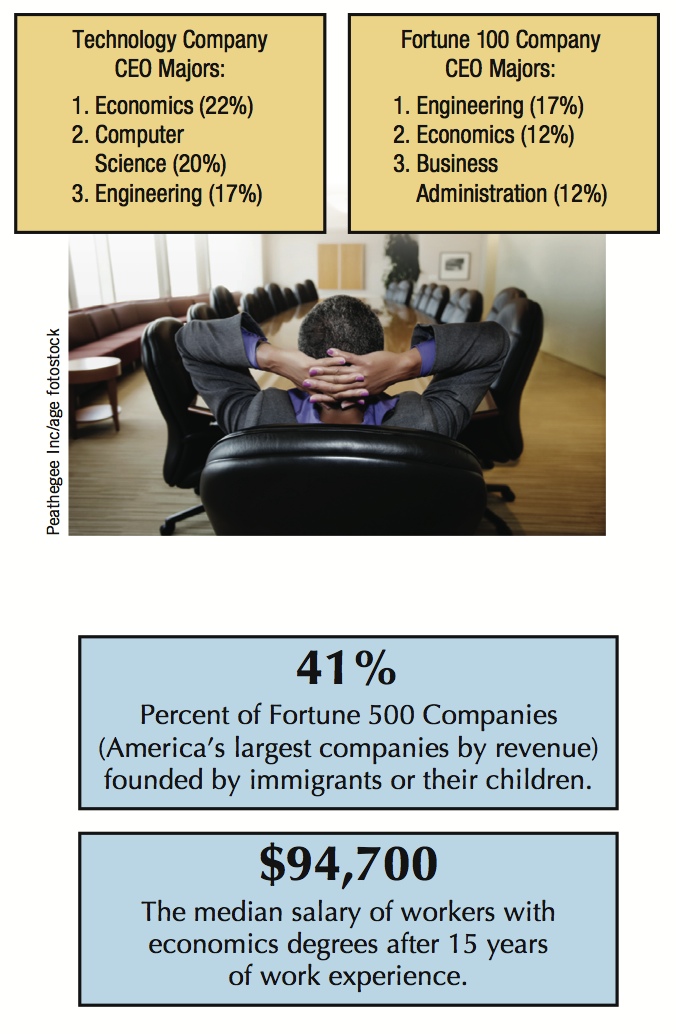

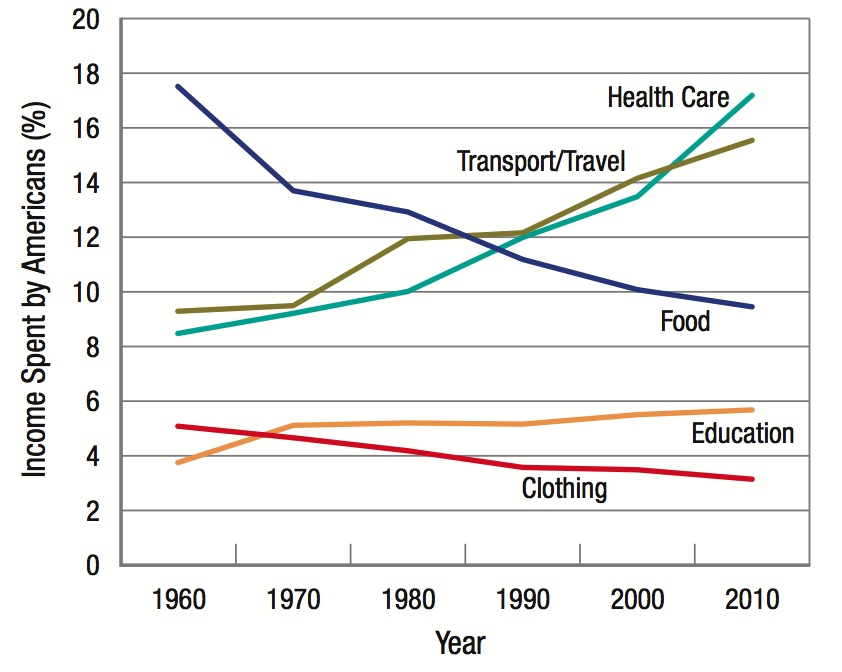

Each chapter in this book includes a By the Numbers box. It has two purposes. First, items in the feature preview some of the topics covered in the chapter. We hope these topics motivate you to read on. Second, the data explosion affecting our understanding of the world will only continue to accelerate. Numerical literacy will grow in importance. This By the Numbers box seeks to encourage a nonthreatening familiarity with data and numbers. At the end of each chapter, there are two Using the Numbers questions to test how well you understood the numbers.

Business majors represented the largest number of college graduates in terms of the total number of bachelor’s degrees granted in 2011. Economics majors represented the sixth most popular degree granted.

The average percentage of income Americans spent on food and clothing has fallen since 1960, but the percentage of income spent on travel, education, and health care has increased.

What do economists do? Common jobs held by economists with bachelor’s degrees and their median salaries.

4

What kind of limitations are we referring to here? It could be money, but money is not the only resource that allows us to achieve the life we want. It’s also our time, our knowledge, our work ethic, and anything else that can be used to achieve our goals. It is this broad notion of economics being the study of how people make decisions to allocate scarce resources to competing wants that allows the subject to be applied to so many topics and applications.

Why Should One Study Economics?

The first answer that might come to mind as to why you are taking this course is “because you have to.” Although economics is a required course for many college students, economics should be thought of as something much, much more. For example, studying economics can prepare you for many types of careers in major industries and government. Studying economics also is a great launching pad for pursuing a graduate degree in law, business, or other fields. More practically speaking, economics helps you to think more clearly about the decisions you make every day and to understand better how the economy functions and why certain things happen the way they do.

incentives The factors that motivate individuals and firms to make decisions in their best interest.

For example, economics has some important things to say about the environment. Most people care about the environment to some degree, and do their part by recycling, not littering, and turning off the lights when leaving a room. But not all people make decisions in the same way: Some might do much more to conserve resources, such as driving less or driving a more fuel efficient car, joining a local organization to plant trees, or even writing to policymakers to support sustainability legislation. The extent to which people participate in environmental activities depends on the benefit they perceive when pursuing such actions compared to the costs, which can include monetary costs, time and effort, and forgone opportunities such as driving a larger, more comfortable car. Economics looks at all of these factors to determine how people make decisions that affect the environment, which affects us all. Economics is a way of thinking about an issue, not just a discipline that has money as its chief focus.

Economists tend to have a rational take on nearly everything. Now all of this “analysis/speculation” may bring only limited insight in some cases, but it gives you some idea of how economists think. We look for rational responses to incentives. Incentives are the factors, both good and bad, that influence how people make decisions. For example, tough admissions requirements for graduate school provide an incentive for students to study harder in college, while lucrative commissions push car salespeople to sell even the ugliest or most unreliable car. Economics is all about how people respond to incentives. We begin most questions by considering how rational people would respond to the incentives that specific situations provide. Sometimes (maybe even often) this analysis leads us down an unexpected path.

Microeconomics Versus Macroeconomics

microeconomics The decision making by individuals, businesses, industries, and governments.

Economics is split into two broad categories: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Microeconomics deals with decision making by individuals, businesses, industries, and governments. It is concerned with issues such as which orange juice to buy, which job to take, and where to go on vacation, as well as which items a business should produce and what price it should charge, and whether a market should be left on its own or be regulated.

Microeconomics looks at how markets are structured. Some markets are very competitive, where many firms offer similar products; while other markets have only one or two large firms, offering little choice. What decisions do businesses make under different market structures? Microeconomics also extends to such topics as labor laws, environmental policy, and health care policy. How can we use the tools of microeconomics to analyze the costs and benefits of differing policies?

macroeconomics The broader issues in the economy such as inflation, unemployment, and national output of goods and services.

5

Macroeconomics, on the other hand, focuses on the broader issues we face as a nation. Most of us don’t care whether an individual buys Nike or Merrell shoes. We do care whether prices of all goods and services rise. Inflation—a general increase in prices economy-wide—affects all of us. So does unemployment (virtually every person will at some point in their life be unemployed, even if it’s just for a short time when switching from one job to another) and economic growth. What decisions do governments make to deal with macroeconomic problems such as inflation and recessions?

Macroeconomics uses microeconomic tools to answer some questions, but its main focus is on the broad aggregate variables of the economy. Macroeconomics has its own terms and topics, such as business cycles, recession, and unemployment. Macroeconomics looks at policies that increase economic growth, the impact of government spending and taxation, the effect of monetary policy on the economy, and inflation. It also looks closely at theories of international trade and international finance. All of these topics have broad impacts on our economy and our standard of living.

Still not clear? Here’s an easy way to remember the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics. Only one letter separates the two terms, so just remember that the “i” in microeconomics refers to “individual” entities (such as a person or a firm), while the “a” in macroeconomics refers to “aggregate” entities (such as cities or a nation as a whole).

Economics is a social science that uses many facts and figures to develop and express ideas. This inevitably involves numbers. For macroeconomics, this means getting used to talking and thinking in huge numbers: billions (nine zeros) and trillions (twelve zeros). Today we are talking about a federal government budget approaching $4 trillion. To wrap your mind around such a huge number, consider how long it would take to spend a trillion dollars if you spent a dollar every second, or $86,400 per day. To spend $1 trillion would require over 31,000 years. And the federal government now spends nearly 4 times this much in one year.

Although we break economics into microeconomics and macroeconomics, there is considerable overlap in the analysis. Both involve the analysis of how individuals, firms, and governments make decisions that affect the lives of people. We use simple supply and demand analysis to understand both individual markets and the general economy as a whole. You will find yourself using concepts from microeconomics to understand fluctuations in the macroeconomy.

Economic Theories and Reality

If you flip through any economics text, you’ll likely see a multitude of graphs, charts, and equations. This book is no exception. The good news is that all of the graphs and charts become relatively easy to understand since they all basically read the same way. The few equations in this book stem from elementary algebra. Once you get through one equation, the rest are similar.

Graphs, charts, and equations are often the simplest and most efficient ways to express data and ideas. Equations are used to express relationships between two variables. Complex and wordy discussions can often be reduced to a simple graph or figure. These are efficient techniques for expressing economic ideas.

Model Building As you study economics this term, you will encounter stylized approaches to a number of issues. By stylized, we mean that economists boil down facts to their basic relevant elements and use assumptions to develop a stylized (simple) model to analyze the issue. There are always situations that lie outside these models, but they are the exception. Economists generalize about economic behavior and reach broadly applicable results.

We begin with relatively simple models, then gradually build to more difficult ones. For example, in the next chapter we introduce one of the simplest models in economics, the production possibilities frontier that illustrates the limits of economic activity. This model has profound implications for the issue of economic growth. We can add in more dimensions and make the model more complex, but often this complexity does not provide any greater insight than the simple model.

6

ceteris paribus Assumption used in economics (and other disciplines as well), where other relevant factors or variables are held constant.

Ceteris Paribus: All Else Held Constant To aid in our model building, economists use the ceteris paribus assumption: “Holding all other things equal.” That means we will hold some important variables constant. For example, to determine how many songs you might be willing to download from iTunes in any given month, we would hold your monthly income constant. We then would change song prices to see the impact on the number purchased (again holding your monthly income constant).

Though model building can lead to surprising insights into how economic actors and economies behave, it is not the end of the story. Economic insights lead to economic theories, but these theories must then be tested. In some cases, such as the extent to which a housing bubble could lead to a financial crisis, economic predictions turned out to be false. Thus, model building is a process—models are created and then tested. If models fail to explain reality, new models are constructed.

Have Smartphones and Social Media Made Life Easier?

Two decades ago, if your professor wanted to convey an important announcement about an upcoming class, she or he would have to wait until the next class period, or if more urgent, make a phone call to each student. Similarly, if you worked for a company, communications with your boss generally ended when you left the office for the day.

Today, we live in a society in which nearly everybody uses online technologies, whether it be for keeping up with friends on Facebook, writing a recommendation for a friend on LinkedIn, or completing homework using classroom management software. Further, we live in a world in which computers and phones are no longer fixed; instead, we carry miniature versions of them with us at all times. According to a Nielsen survey, over 55% of all American adults own a smartphone, and over 75% of those between the ages of 18 and 24 do. So how do these technologies affect our lives?

We can analyze this question using the standard economic benefit versus cost approach. On the benefit side, Internet and mobile technologies have clearly improved the speed and ease of communications, whether staying in touch with family and friends, or trying to locate a loved one at the mall (no more preplanned meeting locations required).

In addition to benefits, there are also costs. For example, greater ease of communications often comes with greater expectations. Several survey studies found that over 95% of Americans answer at least one work-related email or business phone call while on vacation. Students are expected to respond quickly to emails from professors. And even your friends might expect you to respond instantly to text messages and to “like” their latest posts on a social media site. Indeed, sometimes being too connected adds new pressures in life.

Each individual is unique and weighs the benefits and costs of technology differently. How you value these benefits and costs will ultimately determine how you choose to adapt to new and existing technologies. Economics involves all sorts of decisions, including how well connected we choose to be in life.

Efficiency Versus Equity

efficiency How well resources are used and allocated. Do people get the goods and services they want at the lowest possible resource cost? This is the chief focus of efficiency.

equity The fairness of various issues and policies.

Efficiency deals with how well resources are used and allocated. No one likes waste. Much of economic analysis is directed toward ensuring that the most efficient outcomes result from public policy. Production efficiency occurs when goods are produced at the lowest possible cost, and allocative efficiency occurs when individuals who desire a product the most get those goods and services. As an example, it would not make sense for society to allocate to me a large amount of cranberry sauce—I would not eat it. Efficient policies are generally good policies.

The other side of the coin is equity, or fairness. Is it fair that the CEOs of large companies make hundreds of times more money than rank-and-file workers? Many think not. Is it fair that some have so much and others have so little? Again, many think not. There are many divergent views about fairness until we get to extreme cases. When just a few people earn nearly all of the income and control nearly all of a society’s wealth, most people agree that this is unfair.

Throughout this course you will see instances where efficiency and equity collide. You may agree that a specific policy is efficient, but think it is unfair to some group of people. This will be especially evident when you consider tax policy and its impact on income distribution. Fairness, or equity, is a subjective concept, and each of us has different ideas about what is just and fair. When it comes to public policy issues, economics will help you see the tradeoffs between equity and efficiency, but you will ultimately have to make up your own mind about the wisdom of the policy given these tradeoffs.

7

Positive Versus Normative Questions

positive question A question that can be answered using available information or facts.

normative question A question that is based on societal beliefs on what should or should not take place.

Returning to the example in the chapter opener, we ask ourselves many questions whenever a decision needs to be made or an issue is debated. Some questions involve the understanding of basic facts, such as how risky a particular sport is, or how much enjoyment one gets from participating in the sport. Economists call these types of questions positive questions. Positive questions (which need not be positive or upbeat in the literal sense) are questions that can be answered one way or another as long as the information is available. This does not mean that people will always agree on an answer, because facts and information can differ.

Another type of question that arises is how something ought to be, such as whether extreme sports should be banned or whether additional safety measures should be required. Economists call these types of questions normative questions. Normative questions involve societal beliefs on what should or should not be done; differing opinions on an issue can sometimes make normative questions difficult to resolve.

Throughout this book, positive and normative questions will arise, which will play an important role in how individuals and firms make decisions, and how governments form policy proposals that may or may not become law. Indeed, economics encompasses many ideas and questions that affect everyone.

WHAT IS ECONOMICS ABOUT?

- Economics is about making decisions under scarcity, in which wants are unlimited but resources are limited.

- Economics is separated into two broad categories: microeconomics and macroeconomics.

- Microeconomics deals with individuals, firms, and industries and how they make decisions.

- Macroeconomics focuses on broader economic issues such as inflation, employment and unemployment, and economic growth.

- Economics uses a stylized approach, creating simple models that hold all other relevant factors constant (ceteris paribus).

- Economists and policymakers often face a tradeoff between efficiency and equity.

- Positive questions can be answered with facts and information, while normative questions ask how something should or ought to be.

QUESTION: In each of the following situations, determine whether it is a microeconomic or macroeconomic issue.

1. Hewlett-Packard announces that it is lowering the price of its printers by 15%.

2. The president proposes a tax cut.

3. You decide to look for a new job.

4. The economy is in a recession, and the job market is bad.

5. The Federal Reserve announces that it is raising interest rates because it fears inflation.

6. You get a nice raise.

7. Average wages grew by 2% last year.

(1) microeconomics, (2) macroeconomics, (3) microeconomics, (4) macroeconomics, (5) macroeconomics, (6) microeconomics, (7) macroeconomics.

8