Key Principles of Economics

Economics has a set of key principles that show up continually in economic analysis. Some are more restricted to specific issues, but most apply universally. These principles should give you a sense of what you will learn in this course. In the following, we summarize seven key principles that will be applied throughout the entire book. By the end of this course, these principles should be crystal clear and you will likely find yourself using these principles throughout your life, even if you never take another economics course.

Principle 1: Economics Is Concerned with Making Choices with Limited Resources

Economics deals with nearly every type of decision we face every day. But when a typical person is asked what economics is about, the most common answer is “money.” Why is economics commonly misconceived as dealing only with money? This may be due in part to how economics is portrayed in the news—dealing with financial issues, jobs and wages, and the cost of living, among other money matters. While money matters are indeed an important issue studied in economics, you now know that economics involves much, much more.

Economics is about making decisions on allocating limited resources to maximize an individual or society’s well-being. Money is just one source of well-being, assuming that more money makes a person happier, all else equal. But other factors also improve a person’s well-being, such as receiving a day off from work with pay. Even if one does not have a lot of money or free time, satisfaction can come from other activities or events, such as participating in a fun activity with friends or family, or watching one’s favorite team win.

In sum, many aspects of life contribute to the well-being of individuals and of society. Unfortunately, often these are limited by various resource constraints. Therefore, one must think of economics in a broad sense of determining how best to manage all of society’s resources (not just money) in order to maximize well-being. This involves tradeoffs and opportunity costs, which we consider next.

Principle 2: When Making Decisions, One Must Take Into Account Tradeoffs and Opportunity Costs

Wouldn’t it be great if we all had the resources of Mark Zuckerberg (the founder of Facebook) and could buy just about any material possession one could possibly want? Most likely we won’t, so back to reality.

We all have limited resources. Some of us are more limited than others, but each of us, even Mark Zuckerberg, faces limitations (and not because Mark chooses to wear a $30 shirt instead of a $3,000 Brioni suit). For example, we all face time limitations: There are only 24 hours in a day, and some of that must be spent sleeping. The fact that we have many wants but limited resources (scarcity) means that we must make tradeoffs in nearly everything we do. In other words, we have to decide between alternatives, which always exist whenever we make a decision.

opportunity cost The value of the next best alternative; what you give up to do something or purchase something.

How is this accomplished? What factors determine whether you buy a nicer car or use the extra money to pay down debt? Or whether you should spend the weekend at a local music festival or use the time to study for an exam? Economists use an important term to help weigh the benefits and costs of every decision we make, and that term is opportunity cost. In fact, economics is often categorized as the discipline that always weighs benefits against costs.

At its very core, opportunity cost is determined by asking yourself, in any situation, “What could I be doing right now if I wasn’t ____________ (fill in the activity)?” or “What could I have bought if I didn’t buy this _____________ (fill in the last good or service you bought)?” In other words, opportunity cost measures the value of the next best alternative use of your time or money, or what you give up when you make an economic decision. And since there are always alternatives, one cannot avoid opportunity costs.

A common mistake that people make is that they sometimes do not fully take their opportunity costs into account. Have you ever camped out overnight in order to get tickets for a concert? Was it even worth going to the concert? Opportunity cost includes the value of everything you give up in order to attend the concert, including the cost of the tickets and transportation, and the time spent buying tickets, traveling to and from the venue, and of course attending the concert. The sum of all opportunity costs can sometimes outweigh the benefits.

9

Another example of miscalculating opportunity costs occurs when a student spends a copious amount of time to dispute a $15 parking ticket. Like the previous example, the opportunity cost (time and effort disputing the ticket which can be used for some other activity) may exceed the $15 savings if successful and certainly if the attempt to dispute the ticket fails.

In other cases, individuals do respond to opportunity costs. Why do many people choose a paper towel over a hand dryer in a public restroom when given the choice? It’s because the opportunity cost of using the hand dryer is higher than using a paper towel.

Every activity involves opportunity costs. Sleeping, eating, studying, partying, running, hiking, and so on, all require that we spend resources that could be used on another activity. Opportunity cost varies from person to person. A company president rushing from meeting to meeting has a higher opportunity cost than a retired senior citizen, and therefore is more likely to choose the quickest option to accomplish day-to-day activities.

Opportunity costs apply to us as individuals and to societies as a whole. For example, if a country chooses to spend more on environmental conservation, it must use resources that could be used to promote other objectives, such as education and health care.

Principle 3: Specialization Leads to Gains for All Involved

Whenever we pursue an activity or a task, we use time that could be used for other activities or tasks. However, sometimes these other tasks are best left to others to perform. Life would be much more difficult if we all had to grow our own food. This highlights the idea that tradeoffs (especially with one’s time) can lead to better outcomes if one is able to specialize in activities in which she or he is more proficient.

Suppose you and your roommate can each cook your own dinner and clean your own rooms. Alternatively, you might have your roommate clean both rooms (he’s better at it than you) in exchange for you preparing dinner for two (you’re a better cook). Using this arrangement, both tasks are completed in less time since each of you are specializing in the activity you’re better at, plus both of you will benefit from a cleaner apartment and a tastier dinner.

Therefore, specialization in tasks in which one is more proficient can lead to gains for all parties as long as exchange is possible and those involved trade in a mutually beneficial manner. Each person is acting on the opportunity to improve his or her well-being, an example of how incentives affect people’s lives.

Principle 4: People Respond to Incentives, Both Good and Bad

Each time an individual or a firm makes a decision, that person or firm is acting on an incentive that drives the individual or firm to choose an action. These incentives often occur naturally. For example, we choose to eat every day because we face an incentive to survive, and we study and work hard because we face an incentive to be successful in our careers. However, incentives also can be formed by policies set by government to encourage individuals and firms to act in certain ways, and by businesses to encourage consumers to change their consumption habits.

For example, tax policy rests on the idea that people follow their incentives. Do we want to encourage people to save for their retirement? Then let them deduct a certain amount that they can put into a tax-deferred retirement account. Do we want businesses to spend more to stimulate the economy? Then give them tax credits for new investment. Do we want people to go to college? Then give them tax advantages for setting up education savings accounts.

Tax policy is an obvious example in which people follow incentives. But this principle can be seen in action wherever you look. Want to encourage people to fly during the slow travel season? Offer price discounts or bonus frequent flyer miles for flying during that time. Want to spread out the dining time at restaurants? Give early-bird discounts to those willing to eat at 5:00 p.m. rather than at 7:30 p.m.

10

Note that in saying that people follow incentives, economists do not claim that everyone follows each incentive every time. Though you may not want to eat dinner at 5:00 p.m., there might be other people who are willing to eat earlier in return for a price discount.

If not properly constructed, incentives might lead to harmful outcomes. During the 2008 financial crisis, it became clear that the way incentives for traders and executives were set up by Wall Street investment banks was misguided. Traders and executives were paid bonuses based on short-term profits. This encouraged them to take extreme risks to generate quick profits and high bonuses with little regard for the long-term viability of the bank. The bank may be gone tomorrow, but these people still have those huge bonuses.

Responding to badly designed incentives is often described as greed, but they are not always the same. If you found a $20 bill on the sidewalk, would you pick it up? Of course, but would that make you a greedy person? The stranger who accidentally dropped the bill an hour ago might think so, but you are just responding to an incentive to pick up the money before the next lucky person does. Could incentives ever be designed to prevent people from picking up money they find? It may surprise you that one industry has: In many casinos, it is prohibited to keep chips or money you find on the floor.

The natural tendency for society to respond to incentives leads individuals and firms to work hard and generate ideas that increase productivity, a measure of a society’s capacity to produce that determines our standard of living. A worker who can do twice as much as another is likely to earn a higher salary, because productivity and pay tend to go together. The same is true for nations. Countries with the highest standards of living are also the most productive.

Principle 5: Rational Behavior Requires Thinking on the Margin

Have you ever noticed that when you eat at an all-you-can-eat buffet, you always go away fuller than when you order and eat at a non-buffet restaurant? Is this phenomenon unique to you, or is there something more fundamental? Remember, economists look at facts to find incentives to economic behavior.

In this case, people are just rationally responding to the price of additional food. They are thinking on the margin. In a non-buffet restaurant, dessert costs extra, and you make a decision as to whether the enjoyment you receive from the dessert (the marginal benefit) is worth the extra cost (the marginal cost). At the buffet, dessert is free, which means the marginal cost is zero. Even so, you still must ask yourself if dessert will give you satisfaction. If the dessert tastes terrible or adds unwanted calories to your diet, then you might pass on dessert even if it is free. But the fact that one is more likely to have dessert at a buffet than at a menu-based restaurant highlights the notion that people tend to think on the margin.

The idea of thinking on the margin applies to a society as well. Like asking ourselves whether we want another serving of dessert, a society must ask itself whether it wants a little bit more or a little bit less of something, and policymakers and/or citizens vote on such policy proposals. An example of society thinking on the margin is whether taxes should be raised a little to pay for other projects, or whether a country should send up another space exploration craft to study other planets.

Throughout this book, we will see examples of thinking on the margin. A business uses marginal analysis to determine how much of its products it is willing to supply to the market. Individuals use marginal analysis to determine how many hours to exercise or study. And governments use marginal analysis to determine how much pollution should be permitted.

Principle 6: Markets Are Generally Efficient; When They Aren’t, Government Can Sometimes Correct the Failure

Individuals and firms make decisions that maximize their well-being, and markets bring buyers and sellers together. Private markets and the incentives they provide are the best mechanisms known today for providing products and services. There is no government food board that makes sure that bread, cereal, coffee, and all the other food products you demand are on your plate during the day. The vast majority of products we consume are privately provided.

11

Competition for the consumer dollar forces firms to provide products at the lowest possible price, or some other firm will undercut their high price. New products enter the market and old products die out. Such is the dynamic characteristic of markets.

What drives and disciplines markets? Prices and profits are the keys. Profits drive entrepreneurs to provide new products (think of Apple) or existing products at lower prices (think of Wal-Mart). When prices and profits get too high in any market, new firms jump in with lower prices to grab away customers. This competition, or sometimes even the threat of competition, keeps markets from exploiting consumers.

Individuals and firms respond to prices in markets by altering the choices and quantities of goods they purchase and sell, respectively. These actions highlight the ability of markets to provide an efficient outcome for all. Markets can achieve this efficiency without a central planner telling what people should buy or what firms should sell. This phenomenon that markets promote efficiency through the incentives faced by individuals and firms (as if they were guided by an omnipotent force) is referred to as the invisible hand, a term coined by Adam Smith, long considered the father of economics.

As efficient as markets usually are, society does not desire a market for everything. For example, markets for hard drugs or child pornography are largely deemed undesirable. In other cases, a market does not provide enough of a good or service, such as public parks or public education. For these products and services, markets can fail to provide an optimal outcome.

But when markets do fail, they tend to do so in predictable ways. Where consumers have no choice but to buy from one firm (such as a local water company), the market will fail to provide the best solution, and government regulation is often used to protect consumers. Another example is pollution: Left unregulated, companies often will pollute the air and water. Governments then intervene to deal with this market failure. Finally, people rely on information to make rational decisions. When information is not readily available or is known only to one side of the market, markets again can fail to produce the socially desirable outcome.

We also can extend the idea of market efficiency to the greater economy. The market forces of supply and demand generally keep the economy in equilibrium. But occasionally fluctuations in the macroeconomy will occur, and markets take time to readjust on their own. In some cases, the economy becomes stuck in a severe downturn. In these instances, government can smooth the fluctuations in the overall economy by using policies such as government spending or tax cuts. But remember, just because the government can successfully intervene does not mean it always successfully intervenes. The macroeconomy is not a simple machine. Successful policymaking is a tough task.

Principle 7: Institutions and Human Creativity Help Explain the Wealth of Nations

We have seen how individuals and firms make decisions to maximize their well-being, and how tradeoffs, specialization, incentives, and marginal analysis play an important role. We then saw how markets bring buyers and sellers together to promote better outcomes, and that governments sometimes step in when markets fail to produce the best outcome. But how does all of this affect the overall wealth of a nation? Two important factors influencing the wealth of nations are good institutions and human creativity.

12

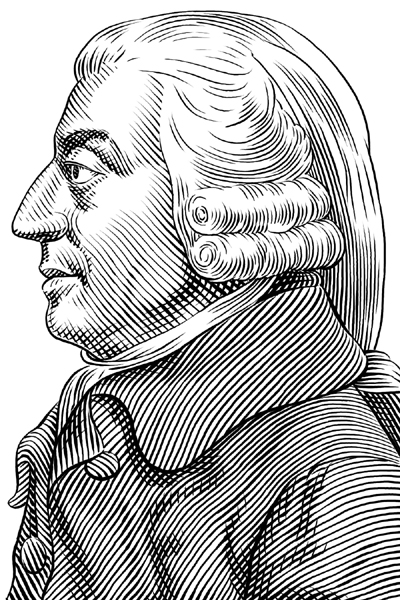

ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)

When Adam Smith was four years old, he was kidnapped and held for ransom. Had his captors not taken fright and returned the boy unharmed, the history of economics might well have turned out differently.

Born in Kirkaldy, Scotland, in 1723, Smith graduated from the University of Glasgow at age 17 and was awarded a scholarship to Oxford. Smith considered his time at Oxford to be largely wasted. Returning to Scotland in 1751, Smith was named Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow.

After 12 years at Glasgow, Smith began tutoring the son of a wealthy Scottish nobleman. This job provided him with the opportunity to spend several years touring the European continent with his young charge. In Paris, Smith met some of the leading French economists of the day, which helped stoke his own interest in political economy. While there, he wrote a friend, “I have begun to write a book in order to pass the time.”

Returning to Kirkaldy in 1766, Smith spent the next decade finishing An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Before publication in 1776, he read sections of the text to Benjamin Franklin. Smith’s genius was in taking the existing forms of economic analysis available at the time and putting them together in a systematic fashion to make sense of the national economy as a whole. Smith demonstrated how individuals left free to pursue their own economic interests end up acting in ways that enhance the welfare of all. This is Smith’s famous “invisible hand.” In Smith’s words: “By directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

How important was Adam Smith? He has been called the “father of political economy.” Many of the foundations of economic analysis we use today are still based on Adam Smith’s writings of several centuries ago.

Sources: Howard Marshall, The Great Economists: A History of Economic Thought (New York: Pitman Publishing, 1967; Paul Strathern, A Brief History of Economic Genius (New York: Texere), 2002; Ian Ross, The Life of Adam Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 1995.

Institutions include a legal system to enforce contracts and laws and to protect the rights of citizens and the ideas they create, a legislative process to develop laws and policies that provide incentives to individuals and firms to work hard, a government free of corruption, and a strong monetary system.

Equally as important as institutions is the ability of societies to create ideas. Ideas change civilizations. Ideas are the basis for creating new products and finding new ways to improve upon existing goods and services. Human creativity starts with a strong educational system, and builds with proper incentives that allow innovation and creativity to flourish into marketable outcomes to improve the lives of all.

Summing It All Up: Economics Is All Around Us

The examples presented in these key principles should have convinced you that economic decisions are a part of our everyday lives. Anytime we make a decision involving a purchase, or decide what we plan to eat, study, or do with our day, we are making economic decisions. Just keep in mind that economics is broader than an exclusive concern with money, despite the great emphasis placed on money in our everyday economic discussions.

Instead, economics is about making decisions when we can’t have everything we want, and how we interact with others to maximize our well-being given limitations. The existence of well-functioning markets allows individuals and firms to come together to achieve good outcomes, and government institutions and policies provide incentives that can lead to a better standard of living for all residents.

The key principles discussed in this chapter will be repeated throughout this book, and you will learn more about these important principles as the term progresses. For now, realize that economics rests on the foundation of a limited number of important principles. Once you fully grasp these basic ideas, the study of economics will be both rewarding and exciting, because after this course you will discover and appreciate how much more you understand the world around you.

13

Do Economists Ever Agree on Anything?

Give me a one-handed economist! All my economists say, “on one hand… on the other.”

Harry S Truman

President Truman once exclaimed that the country needed more one-handed economists. What did he mean by that? He was saying that anytime an economist talks about a solution to an economic problem, the economist will often follow that statement by saying “on the other hand…”.

This story highlights the point that every issue can be viewed from different perspectives, so much so that economists seemingly disagree with one another on everything. Solutions often depend on how benefits and costs are measured. For example, suppose we debate whether gasoline taxes are too high. On the one hand, higher gasoline taxes will reduce oil consumption, reduce pollution, reduce traffic congestion, and generate money to promote public transportation such as buses, subways, and high-speed trains. On the other hand, higher gasoline taxes result in higher prices for most consumer goods due to higher transportation costs, and higher prices for gas and consumer goods affect lower-income households more since they spend a greater share of their money on such goods.

Different opinions about the relative weights of benefits and costs make economic policymaking challenging. Economic conditions are always changing. This is why economists rely so much on models and assumptions in order to prescribe a solution based on the conditions facing the economy.

But despite differences and frequent disagreements in economic policy, a recent survey of the IGM Economic Experts Panel, consisting of forty-one prominent economists from all different schools of thought, found that economists do agree on many things. First, most economists agree that specialization in activities leads to gains to all parties involved. Second, most economists agree that markets and competition promote efficiency. Third, most economists believe that stimulus programs and bailout packages do reduce unemployment (though not all believe such measures are worth their costs). Fourth, most economists believe flexible exchange rates are ideal. And finally, most economists believe that individuals and firms respond to incentives.

In sum, despite the constant bickering one often hears in economic policy debates, economists agree on a number of issues, and these are typically grounded in the key economic principles described in this chapter.

KEY PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS

- Economics is concerned with making choices with limited resources.

- When making decisions, one must take into account tradeoffs and opportunity costs.

- Specialization leads to gains for all involved.

- People respond to incentives, both good and bad.

- Rational behavior requires thinking on the margin.

- Markets are generally efficient; when they aren’t, government can sometimes correct the failure.

- Institutions and human creativity help explain the wealth of nations.

QUESTION: McDonald’s introduced a premium blend of coffee that sells for more than its standard coffee. How does this represent thinking at the margin?

McDonald’s is adding one more product (premium coffee) to its line. Thinking at the margin entails thinking about how you can improve an operation (or increase profits) by adding to your existing product line or reducing costs.

14