Demand

Whenever you purchase a product, you are voting with your money. You are selecting one product out of many and supporting one firm out of many, both of which signal to the business community what sorts of products satisfy your wants as a consumer.

Economists typically focus on wants rather than needs because it is so difficult to determine what we truly need. Theoretically, you could survive on tofu and vitamin pills, living in a lean-to made of cardboard and buying all your clothes from thrift stores. Most people in our society, however, choose not to live in such austere fashion. Rather, they want something more, and in most cases they are willing and able to pay for more.

Willingness-to-Pay: The Building Block of Market Demand

willingness-to-pay An individual’s valuation of a good or service, equal to the most an individual is willing and able to pay.

Imagine sitting in your economics class around mealtime. In your rush to class, you did not have a chance to make a sandwich at home or to stop at the cafeteria on your way to class. You think about foods that sound appealing to you (just about anything at this point), and plan to go to the cafeteria immediately after class and buy a sandwich. Given your growling stomach, you think more about what you want on your sandwich and less about how much the sandwich will cost. In your mind, your willingness-to-pay for that sandwich can be quite high, say $10 or even more.

Economists refer to willingness-to-pay as the maximum amount one would be willing to pay for a good or service, which represents the highest value that a consumer believes the good or service is worth. Of course, one always hopes that the actual price would be much lower. In your case, willingness-to-pay is the cutoff from buying a sandwich and not buying a sandwich.

Willingness-to-pay varies from person to person, from the circumstances each person is in to the number of sandwiches one chooses to buy. Suppose your classmate ate a full meal before she came to class. Her willingness-to-pay for a sandwich would be much lower than yours because she isn’t hungry at that moment. Similarly, after you buy and consume your first sandwich, your willingness-to-pay for a second sandwich would decrease because you would be less hungry. The desires consumers have for goods and services that are expressed through their purchases are known as demands in the market.

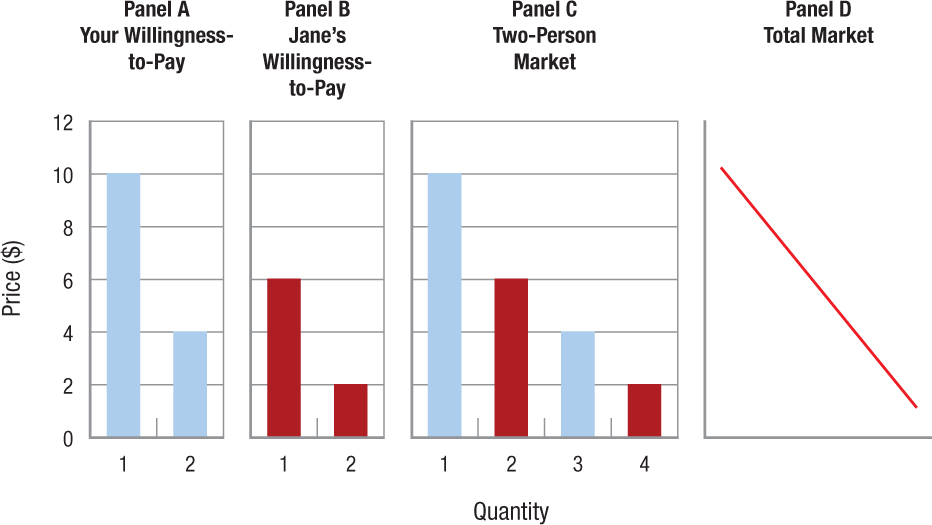

Figure 1 below illustrates how individuals’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) is used to derive market demand curves. Suppose you are willing to pay up to $10 for the first sandwich and $4 for the second sandwich (shown in panel A), while Jane, your less-hungry classmate, would pay up to $6 for her first sandwich and only $2 for her second sandwich (shown in panel B). If we take the WTP for your two sandwiches and the WTP of Jane’s two sandwiches and place all four values in order from highest to lowest, a two-person market for sandwiches is created as shown in panel C. Notice how the distance between steps becomes smaller in the two-person market. Now suppose we combine the WTPs for everybody in the class (or for an entire city or country) into a single market. What would that diagram look like? In large markets, the difference in WTP between each unit of a good becomes so small that it becomes a straight line, as shown in panel D.

FIGURE 1

From Individual Willingness-to-Pay to Market Demand In panel A, you would be willing to pay up to $10 for your first sandwich and $4 for the second. Jane, however, is only willing to pay up to $6 for her first sandwich and $2 for a second (panel B). Placing the WTP for sandwiches by you and Jane in order from the highest to lowest value, we generate a market with two consumers shown in panel C. As more and more individuals are added to the market, the demand for sandwiches becomes a smooth downward-sloping line, shown in panel D.

56

These illustrations show how ordinary demand curves, which we will discuss in detail in the remainder of this section, are developed from the perceptions of what individual consumers believe a good or service is worth to them (their willingness-to-pay). Let’s now discuss an important characteristic of market demand.

The Law of Demand: The Relationship Between Quantity Demanded and Price

demand The maximum amount of a product that buyers are willing and able to purchase over some time period at various prices, holding all other relevant factors constant (the ceteris paribus condition).

Demand refers to the goods and services people are willing and able to buy during a certain period of time at various prices, holding all other relevant factors constant (the ceteris paribus condition). Typically, when the price of a good or service increases (say your favorite café raises its prices), the quantity demanded will decrease because fewer and fewer people will be willing and able to spend their money on such things. However, when prices of goods or services decrease (think of sales offered the day after Thanksgiving), the quantity demanded increases.

law of demand Holding all other relevant factors constant, as price increases, quantity demanded falls, and as price decreases, quantity demanded rises.

In a market economy, there is a negative relationship between price and quantity demanded. This relationship, in its most basic form, states that as price increases, the quantity demanded falls, and conversely, as prices fall, the quantity demanded increases.

This principle, when all other factors are held constant, is known as the law of demand. The law of demand states that the lower a product’s price, the more of that product consumers will purchase during a given time period. This straightforward, commonsense notion happens because, as a product’s price drops, consumers will substitute the now cheaper product for other, more expensive products. Conversely, if the product’s price rises, consumers will find other, less expensive products to substitute for it.

To illustrate, when videocassette recorders first came on the market 30 years ago, they cost $3,000, and few homes had one. As VCRs became less and less expensive, however, more people bought them, and others found more uses for them. Today, DVD players and digital video recorders (DVRs) are everywhere, and VCRs are essentially consigned to museums. Digital music players have altered the structure of the music business, and digital cameras have essentially replaced cameras that use film.

57

Time is an important component in the demand for many products. Consuming many products—watching a movie, eating a pizza, playing tennis—takes some time. Thus, the price of these goods includes not only their monetary cost, but also the opportunity cost of the time needed to consume them. It follows that, all other things being equal, including the cost of a ticket, we would expect more consumers to attend a two-hour movie than a four-hour movie. The shorter movie simply requires less of a time investment.

The Demand Curve

demand curve A graphical illustration of the law of demand, which shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded.

demand schedule A table that shows the quantity of a good a consumer purchases at each price.

The law of demand states that as price decreases, quantity demanded increases. When we translate demand information into a graph, we create a demand curve. This demand curve, which slopes down and to the right, graphically illustrates the law of demand. A demand curve shows both the willingness-to-pay for any given quantity and what the quantity demanded will be at any given price. In Figure 1, we saw how individual demands (measured by willingness-to-pay) can be combined to represent market demand, which can consist of many consumers. For simplicity, from this point we will assume that all demand curves, including those for individuals, are linear (straight lines).

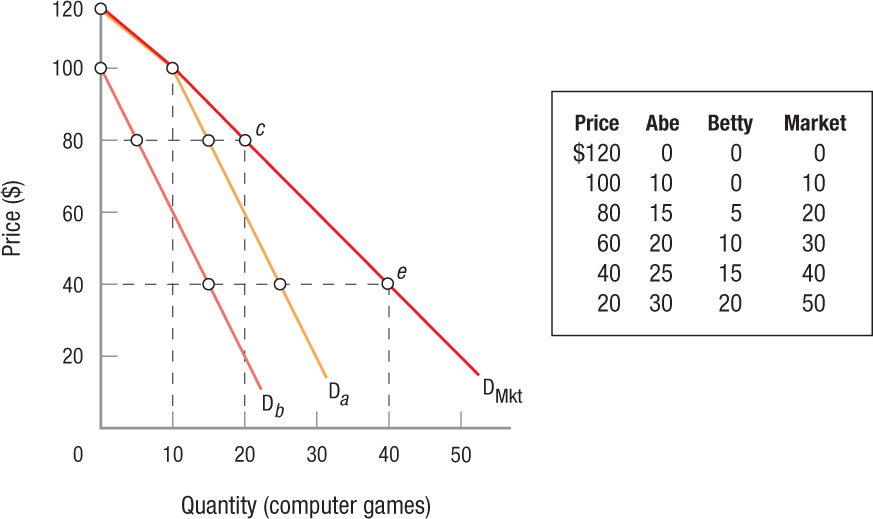

Suppose Abe and Betty are the only two consumers in the market for computer games. Figure 2 shows each of their annual demands using a demand schedule and a demand curve. A demand schedule is a table indicating the quantities consumers are willing to purchase at each price. Looking at the demand schedule, we can see that both Abe and Betty are willing to buy more computer games as the price decreases. When the price is $100, Abe is willing to buy 10 games while Betty buys none. When the price falls to $80, Abe is willing to buy 15 games and Betty would buy 5.

FIGURE 2

Market Demand: Horizontal Summation of Individual Demand Curves Abe and Betty’s demand schedules (the table) and their individual demand curves (the graph) for computer games are shown. Abe will purchase 15 computer games when the price is $80, buy 25 games when the price falls to $40, and buy more as prices continue to fall. Betty will purchase 5 computer games when the price is $80 and buy 15 when the price falls to $40. The individual demand curves for Abe and Betty are shown as Da and Db, respectively, and are horizontally summed to get market demand, DMkt. Horizontal summation involves adding together the quantities demanded by each individual at each possible price.

We can take the values from the demand schedule in the table and graph them in a figure, with price shown on the vertical axis and computer games on the horizontal axis, following the convention in economics of always placing price on the vertical axis and quantity demanded on the horizontal axis. By doing so, we can create a demand curve for both Abe and Betty. Both the table and the graph convey the same information. They also both portray the law of demand. As the price decreases, Abe and Betty demand more computer games.

horizontal summation Market demand and supply curves are found by adding together how many units of the product will be purchased or supplied at each price.

Although individual demand curves are interesting, market demand curves are far more important to economists, as they can be used to predict changes in product price and quantity. Further, one can observe what happens to a product’s price and quantity and infer what changes have occurred in the market. Market demand is the sum of individual demands. To calculate market demand, economists simply add together how many units of a product all consumers will purchase at each price. This process is known as horizontal summation.

58

Turning to the demand curves in Figure 2, two individual demand curves for Abe and Betty, Da and Db, are shown. For simplicity, let’s assume they represent the entire market, but recognize that this process would work for any larger number of people. Note that at a price of $100 a game, Betty will not buy any, although Abe is willing to buy 10 games at $100 each. Above $100, therefore, the market demand is equal to Abe’s demand. At $100 and below, however, we add both Abe’s and Betty’s demands at each price to obtain market demand. Thus, at $80, individual demand is 15 for Abe and 5 for Betty, therefore the market demand is equal to 20 (point c). When the price is $40 a game, Abe buys 25 and Betty buys 15, for a total of 40 games (point e). The heavier curve, labeled DMkt, represents this market demand; it is a horizontal summation of the two individual demand curves.

This all sounds simple in theory, but in the real world estimating market demand curves is a tricky business, given that many markets contain millions of consumers. Economic analysts and marketing professionals use sophisticated statistical techniques to estimate the market demand for particular goods and services in the industries they represent.

The market demand curve shows the maximum amount of a product consumers are willing and able to purchase during a given time period at various prices, all other relevant factors being held constant. Economists use the term determinants of demand to refer to these other, nonprice factors that are held constant. This is another example of the use of ceteris paribus: holding all other relevant factors constant.

Determinants of Demand

determinants of demand Nonprice factors that affect demand, including tastes and preferences, income, prices of related goods, number of buyers, and expectations.

Up to this point, we have discussed only how price affects the quantity demanded. When prices fall, consumers purchase more of a product, thus quantity demanded rises. When prices rise, consumers purchase less of a product, thus quantity demanded falls. But several other factors besides price also affect demand, including what people like, what their income is, and how much related products cost. More specifically, there are five key determinants of demand: (1) tastes and preferences; (2) income; (3) prices of related goods; (4) the number of buyers; and (5) expectations regarding future prices, income, and product availability. When one of these determinants changes, the entire demand curve changes. Let’s see why.

Tastes and Preferences We all have preferences for certain products over others, easily perceiving subtle differences in styling and quality. Automobiles, fashions, phones, and music are just a few of the products that are subject to the whims of the consumer.

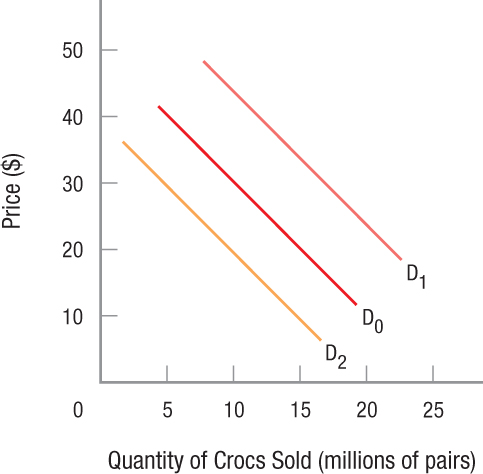

Remember Crocs, those brightly colored rubber sandals with the little air holes that moms, kids, waitresses, and many others favored recently? They were an instant hit. Initially, demand was D0 in Figure 3. They then became such a fad that demand jumped to D1 and for a short while Crocs were hard to find. Eventually Crocs were everywhere. Fads come and go, and now the demand for them settled back to something like D2, less than the original level. Notice an important distinction here: More Crocs weren’t sold because the price was lowered; the entire demand curve shifted rightward when they were hot and more Crocs could be sold at all prices. Now that the fad has subsided, fewer can be sold at all prices. It is important to keep in mind that when one of the determinants changes, such as tastes and preferences in this case, the entire demand curve shifts.

FIGURE 3

Shifts in the Demand Curve The demand for Crocs originally was D0. When they became a fad, demand shifted to D1 as consumers were willing to purchase more at all prices. Once the fad cooled off, demand fell (shifted leftward) to D2 as consumers wanted less at each price. When a determinant such as tastes and preferences changes, the entire demand curve shifts.

normal good A good for which an increase in income results in rising demand.

inferior good A good for which an increase in income results in declining demand.

Income Income is another important factor influencing consumer demand. Generally speaking, as income rises, demand for most goods will likewise increase. Get a raise, and you are more likely to buy more clothes and acquire the latest technology gadgets. Your demand curve for these goods will shift to the right (such as from D0 to D1 in Figure 3). Products for which demand is positively linked to income—when income rises, demand for the product also rises—are called normal goods.

59

There are also some products for which demand declines as income rises, and the demand curve shifts to the left. Economists call these products inferior goods. As income grows, for instance, the consumption of discount clothing and cheap motel stays will likely fall as individuals upgrade their wardrobes and stay in more comfortable hotels when traveling. Similarly, when you graduate from college and your income rises, your consumption of ramen noodles will fall as you begin to cook tastier dinners and eat out more frequently.

substitute goods Goods consumers will substitute for one another depending on their relative prices. When the price of one good rises and the demand for another good increases, they are substitute goods, and vice versa.

complementary goods Goods that are typically consumed together. When the price of a complementary good rises, the demand for the other good declines, and vice versa.

Prices of Related Goods The prices of related commodities also affect consumer decisions. You may be an avid concertgoer, but with concert ticket prices often topping $100, further rises in the price of concert tickets may entice you to see more movies and fewer concerts. Movies, concerts, plays, and sporting events are good examples of substitute goods, because consumers can substitute one for another depending on their respective prices. When the price of concerts rises, your demand for movies increases, and vice versa. These are substitute goods.

Movies and popcorn, on the other hand, are examples of complementary goods. These are goods that are generally consumed together, such that an increase or decrease in the consumption of one will similarly result in an increase or decrease in the consumption of the other—see fewer movies, and your consumption of popcorn will decline. Other complementary goods include cars and gasoline, hot dogs and hot dog buns, and ski lift tickets and ski rentals. Thus, when the price of lift tickets increases, the quantity of lift tickets demanded falls, which causes your demand for ski rentals to fall as well (shifts to the left), and vice versa.

The Number of Buyers Another factor influencing market demand for a product is the number of potential buyers in the market. Clearly, the more consumers there are who would be likely to buy a particular product, the higher its market demand will be (the demand curve will shift rightward). As our average life span steadily rises, the demands for medical services and retirement communities likewise increase. As more people than ever enter universities and graduate schools, demand for textbooks and backpacks increases.

Expectations About Future Prices, Incomes, and Product Availability The final factor influencing demand involves consumer expectations. If consumers expect shortages of certain products or increases in their prices in the near future, they tend to rush out and buy these products immediately, thereby increasing the present demand for the products. The demand curve shifts to the right. During the Florida hurricane season, when a large storm forms and begins moving toward the coast, the demand for plywood, nails, bottled water, and batteries quickly rises.

The expectation of a rise in income, meanwhile, can lead consumers to take advantage of credit in order to increase their present consumption. Department stores and furniture stores, for example, often run “no payments until next year” sales designed to attract consumers who want to “buy now, pay later.” These consumers expect to have more money later, when they can pay, so they go ahead and buy what they want now, thereby increasing the present demand for the sale items. Again, the demand curve shifts to the right.

60

The key point to remember from this section is that when one of the determinants of demand changes, the entire demand curve shifts rightward (an increase in demand) or leftward (a decline in demand). A quick look back at Figure 3 shows that when demand increases, consumers are willing to buy more at all prices, and when demand decreases, they will buy less at all prices.

Changes in Demand Versus Changes in Quantity Demanded

When the price of a product rises, consumers simply buy fewer units of that product. This is a movement along an existing demand curve. However, when one or more of the determinants change, the entire demand curve is altered. Now at any given price, consumers are willing to purchase more or less depending on the nature of the change. This section focuses on this important distinction between changes in demand versus changes in quantity demanded.

change in demand Occurs when one or more of the determinants of demand changes, shown as a shift in the entire demand curve.

Changes in demand occur whenever one or more of the determinants of demand change and demand curves shift. When demand changes, the demand curve shifts either to the right or to the left. Let’s look at each shift in turn.

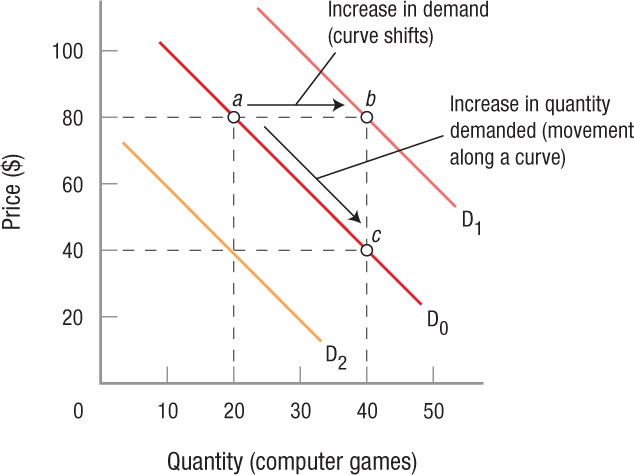

Demand increases when the entire demand curve shifts to the right. At all prices, consumers are willing to purchase more of the product in question. Figure 4 shows an increase in demand for computer games; the demand curve shifts from D0 to D1. Notice that more computer games are purchased at all prices along D1 as compared to D0.

FIGURE 4

Changes in Demand Versus Changes in Quantity Demanded A shift in the demand curve from D0 to D1 represents an increase in demand, and consumers will buy more of the product at each price. A shift from D0 to D2 reflects a decrease in demand. Movement along D0 from point a to point c indicates an increase in quantity demanded; this type of movement can only be caused by a change in the price of the product.

change in quantity demanded Occurs when the price of the product changes, shown as a movement along an existing demand curve.

Now look at a decrease in demand, when the entire demand curve shifts to the left. At all prices, consumers are willing to purchase less of the product in question. A drop in consumer income is normally associated with a decrease in demand (the demand curve shifts to the left, as from D0 to D2 in Figure 4).

Whereas a change in demand can be brought about by many different factors, a change in quantity demanded can be caused by only one thing: a change in product price. This is shown in Figure 4 as a reduction in price from $80 to $40, resulting in sales (quantity demanded) increasing from 20 (point a) to 40 (point c) games. This distinction between a change in demand and a change in quantity demanded is important. Reducing price to increase sales is different from spending a few million dollars on Super Bowl advertising to increase sales at all prices.

These concepts are so important that a quick summary is in order. As Figure 4 illustrates, given the initial demand D0, increasing sales from 20 to 40 games can occur in either of two ways. First, changing a determinant (say, increasing advertising) could shift the demand curve to D1 so that 40 games would be sold at $80 (point b). Alternatively, 40 games could be sold by reducing the price to $40 (point c). Selling more by increasing advertising causes an increase in demand, or a shift in the entire demand curve. Simply reducing the price, on the other hand, causes an increase in quantity demanded, or a movement along the existing demand curve, D0, from point a to point c.

61

DEMAND

- A person’s willingness-to-pay is the maximum amount she or he values a good to be worth at a particular moment in time and is the building block for demand.

- Demand refers to the quantity of products people are willing and able to purchase at various prices during some specific time period, all other relevant factors being held constant.

- The law of demand states that price and quantity demanded have an inverse (negative) relation: As price rises, consumers buy fewer units; as price falls, consumers buy more units. It is depicted as a downward-sloping demand curve.

- Demand curves shift when one or more of the determinants of demand change.

- The determinants of demand are consumer tastes and preferences, income, prices of substitutes and complements, the number of buyers in a market, and expectations about future prices, incomes, and product availability.

- A shift of a demand curve is a change in demand, and occurs when a determinant of demand changes.

- A change in quantity demanded occurs only when the price of a product changes, leading consumers to adjust their purchases along the existing demand curve.

QUESTIONS: Sales of electric plug-in hybrid cars are on the rise. The Chevrolet Volt is selling well, despite being priced almost double that of similar-sized gasoline-only cars in Chevrolet’s line. Other manufacturers are adding plug-in hybrids to their lines at an astonishing pace. What has been the cause of the rising sales of plug-in hybrids? Is this an increase in demand or an increase in quantity demanded?

Rising gasoline prices, a general rise in environmental consciousness, and incentives (such as preferred parking and reduced tolls offered by some states) have caused the demand for plug-in hybrids to swell. This is a change in demand, because factors other than the price of the car itself have led to an increase in demand for such cars.