Taxes and Elasticity

On average, families pay more than 40% of their income in taxes, including income, property, estate, sales, and excise taxes. (An excise tax is a sales tax applied to a specific product, such as gasoline or tobacco.) Add to this the taxes that are embedded into the goods and services we buy, such as tariffs (taxes) on imports, tourism taxes, and airport security taxes, and it’s no wonder that taxes are a perennial issue of debate among policymakers and their constituents.

Nobody likes paying taxes, but they are necessary to provide many of the public goods and services (such as roads, national defense, police protection, public education, clean air, and parks) from which everybody receives some benefit. The questions economists deal with are how to determine the efficient level of taxation and what is the most efficient way to reach that level?

Taxes can be separated into two general categories: taxes on income sources and taxes on spending. We now study how the economic burden of both categories of taxes can vary depending on how the tax policy is designed (in the case of income) and on the elasticity of the good or service being purchased (in the case of spending).

We begin by studying the various ways taxes are collected on income.

Taxes on Income Sources and Their Economic Burden

progressive tax A tax that rises in percentage of income as income increases.

Flat tax A tax that is a constant proportion of one’s income.

regressive tax A tax that falls in percentage of income as income increases.

lump-sum tax A fixed amount of tax regardless of income, and is a type of regressive tax.

Taxes on income sources constitute the largest source of revenues for the federal government and many state governments. The most common types of taxes include individual income tax, payroll tax (i.e., Social Security tax), corporate income tax, dividend tax (taxes on earnings from financial assets), and capital gains tax (taxes on the rising values of assets such as property and financial instruments when sold).

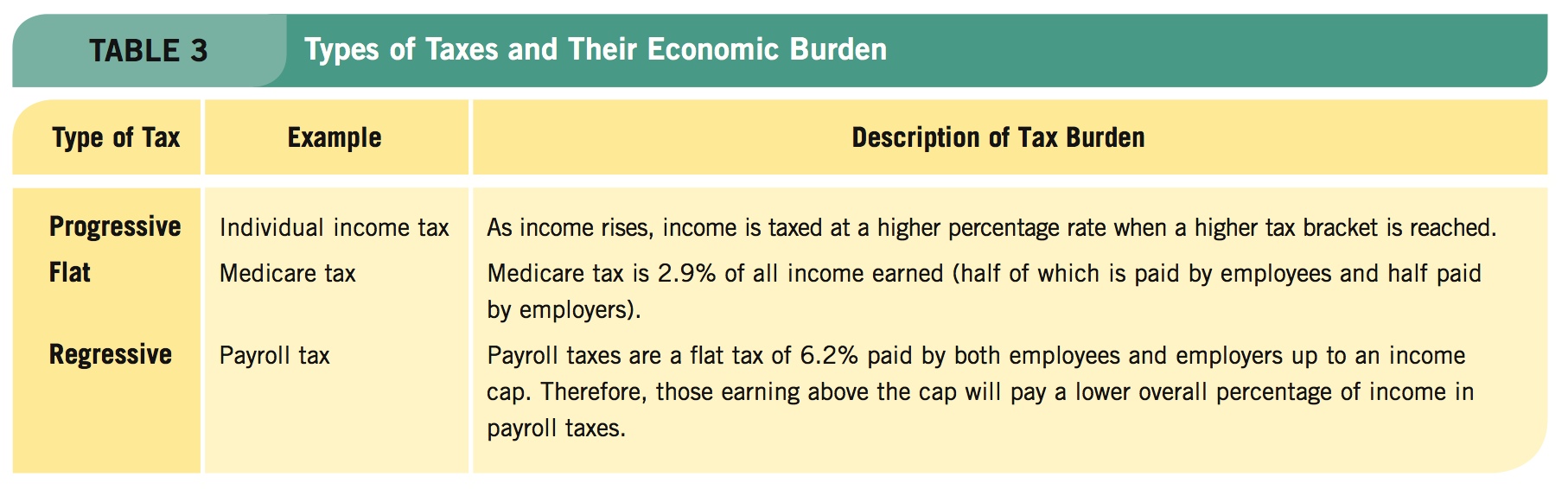

Much of the debate on the economic burden of income taxes focuses on whether taxes are progressive, flat, or regressive with respect to income earned. Progressive taxes are those that rise in burden as income increases. Flat taxes take a constant percentage of one’s income. Regressive taxes fall in burden as income increases, which means that individuals with lower incomes pay a greater percentage of their income in taxes than individuals with higher incomes. A type of regressive tax is called a lump-sum tax, which takes a fixed amount of tax regardless of income earned, and therefore falls in percentage as income rises. Table 3 lists the three categories of taxes and provides an example of an actual tax that falls within each category.

119

Taxes on Spending and the Incidence of Taxation

The typical household pays a substantial amount of taxes on goods and services. Almost everybody pays sales taxes on goods and services purchased, homeowners pay property taxes each year on the value of their homes, and all sorts of excise taxes exist on everything from car rentals and hotel stays to gasoline purchases.

Although income taxes typically represent the largest burden on most households, taxes on spending are sometimes larger for certain groups of people. For example, households with very low incomes often pay little to no income taxes, but pay a sizeable portion of their income in sales and excise taxes. Similarly, wealthy households often receive most of their income by way of investment earnings, which are taxed at a lower rate than traditional income earnings; for these households, taxes paid on property (often on multiple homes) and luxury taxes (on yachts and other expensive toys) may constitute a larger portion of their tax burden.

incidence of taxation Refers to who bears the economic burden of a tax. The economic entity bearing the burden of a particular tax will depend on the price elasticities of demand and supply.

In sum, taxes on spending are not trivial, and elasticity plays an important role in determining the impact of these various taxes on individuals, families, and businesses. Economists studying taxes are interested in the incidence of taxation and in shifts in the tax burden. The incidence of a tax refers to who bears its economic burden. Statutes determine what is taxed, who must pay various taxes, and what agencies are responsible for collecting taxes and remitting the revenue collected. Even so, the individuals, firms, or groups paying a tax may not be the ones bearing its economic burden. This burden can be shifted onto others. Considering the elasticities of demand and supply will help us determine the incidence of various taxes—who really bears the tax burden—and thus the ultimate impact of various tax policies.

Let’s now analyze how the elasticity of a good or service can affect the incidence of taxation. To simplify the analysis, we will focus on excise taxes for the remainder of this section.

Elasticity of Demand and Tax Burdens

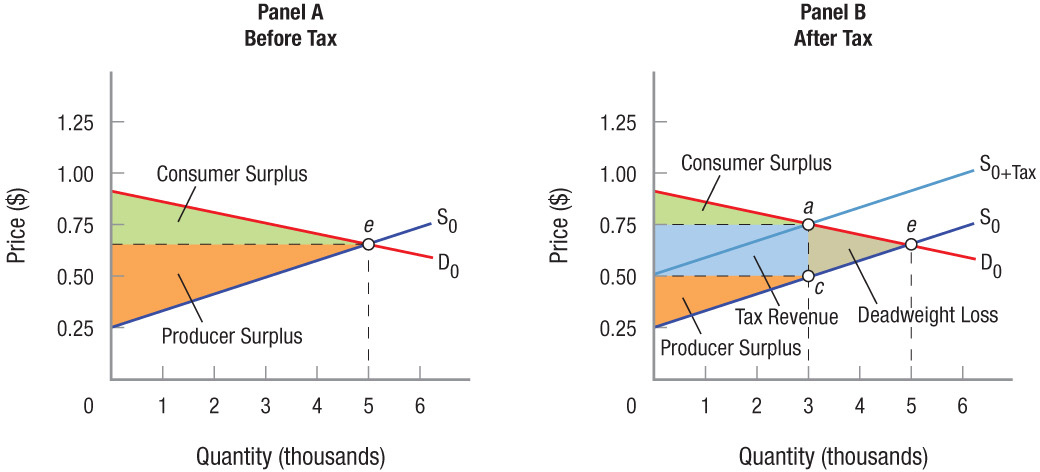

Let us consider what happens when an excise tax is levied on a product with elastic demand, such as strawberries. Panel A of Figure 7 shows the market before an excise tax is imposed. The initial supply curve (S0) is supply before the tax and demand curve D0 reflects demand. Originally, the market is in equilibrium at point e, at which 5,000 baskets are sold for 65 cents each.

FIGURE 7

Tax Burden with Relatively Elastic Demand S0 is the initial supply curve for a product with elastic demand (panel A). When a 25 cent excise tax is placed on the product, the supply curve shifts upward by the amount of the tax, S0+Tax (panel B). With demand remaining constant at D0, equilibrium moves to point a (3,000 units). In this case, output falls substantially when the tax is imposed because elastic demand means extreme price sensitivity. As a result, sellers end up bearing most of the burden of this tax, and the deadweight loss is relatively large (area cae).

120

In panel B, we now add a per unit tax—say, 25 cents a basket—paid by the grower. This, in effect, adds 25 cents to the cost for each basket and adds a wedge between what consumers pay and what growers receive. Supply curve S0 therefore shifts upward by this amount, to S0+Tax. The new supply curve runs parallel to S0, with the distance the curve has shifted (ac) equaling the 25 cent tax per basket collected by the government.

Assuming demand remains constant at D0, the new equilibrium is at point a, with 3,000 baskets sold for a price of 75 cents each. The producer receives 75 cents per basket, of which it must send 25 cents to the government, keeping 50 cents for itself. Keep in mind that, because this demand is elastic, many consumers are not really willing to pay a higher price for the product; this is why output declines so much and why sellers bear most of the burden of this tax.

Before the tax, both consumer and producer surplus (discussed in Chapter 4) in panel A were substantial. After the tax, the government collects revenue equal to the tax (25 cents) times the number of baskets sold (3,000), or $750 (the blue area), consumer surplus now equals the area above the blue section, and producer surplus equals the area below it. Note that consumers and producers lose surplus equal not only to the revenue gained by the government but also to area cae, which represents a deadweight loss. Although this area is lost to society as a result of the tax, how the tax revenues are used to benefit society determines whether society is better or worse off with the tax.

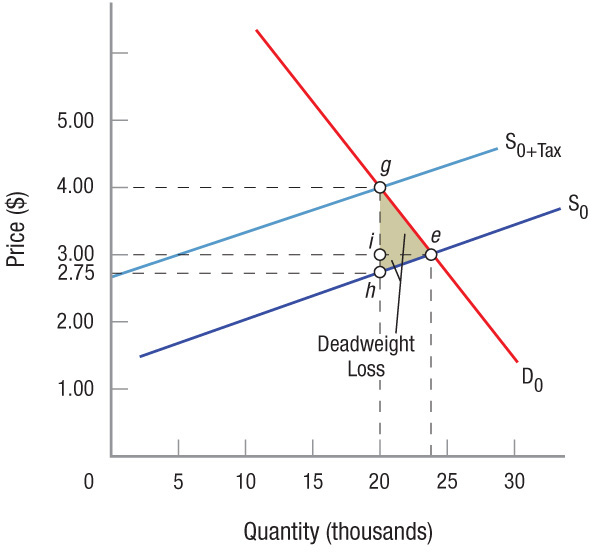

Contrast this situation with the impact of an excise tax when the demand is inelastic (e.g., cigarettes), as in Figure 8. Initially, 23,000 packs are sold at $3.00 per pack. With a $1.25 tax, supply shifts to S0+Tax, market equilibrium moves to point g, price increases from $3.00 to $4.00 per pack, and output declines from 23,000 to 20,000. Inelastic demands are price insensitive, therefore output declines much less when this tax is imposed. The $1.25 tax in this case is gh, with consumers paying gi (a dollar), sellers paying ih (25 cents), and a deadweight loss equal to area hge. In general, deadweight losses are small when demand is inelastic. A small quantity reduction given a higher price means that nearly all the excise tax is shifted forward to consumers. In this case, consumers pay an additional $1.00 for each unit, but manufacturers end up bearing only a small burden (25 cents).

FIGURE 8

Tax Burden with Relatively Inelastic Demand S0 is the initial supply curve for a product with inelastic demand. When a $1.25 excise tax is placed on the product, the supply curve shifts upward by the amount of the tax, to S0+Tax. Assuming demand remains constant at D0, the new equilibrium will be at point g. Because this demand curve is inelastic, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for the product, and bear nearly all the burden of the tax. The deadweight loss (area hge) is relatively small when demand is inelastic.

We can generalize about the effects of elasticity of demand on the tax burden. For a given supply of some product, the greater the price elasticity of demand, the lower the share of the total tax burden shifted to consumers and the greater the share borne by sellers, and vice versa.

121

This analysis shows why proposals to raise excise taxes usually focus on such inelastically demanded commodities as tobacco, gasoline, and alcohol. For products with inelastic demands, the reduction in output is lower when prices rise because of the tax—most smokers keep smoking even when the tobacco tax goes up. Therefore, these taxes generate more revenue than would excise taxes on elastically demanded products. Proposals to raise excise taxes are often cloaked in public health and welfare rhetoric, politicians finding it easier to sell the idea of taxes that punish “sins” such as smoking and drinking. However, if the products in question did not have inelastic demands, the tax revenues generated by such taxes would be small. Because consumers substantially reduce their purchases when demand is elastic, many workers in the industries with such elastically demanded products would become unemployed. As a result, such taxes are rarely enacted on products with elastic demands.

Elasticity of Supply and Tax Burdens

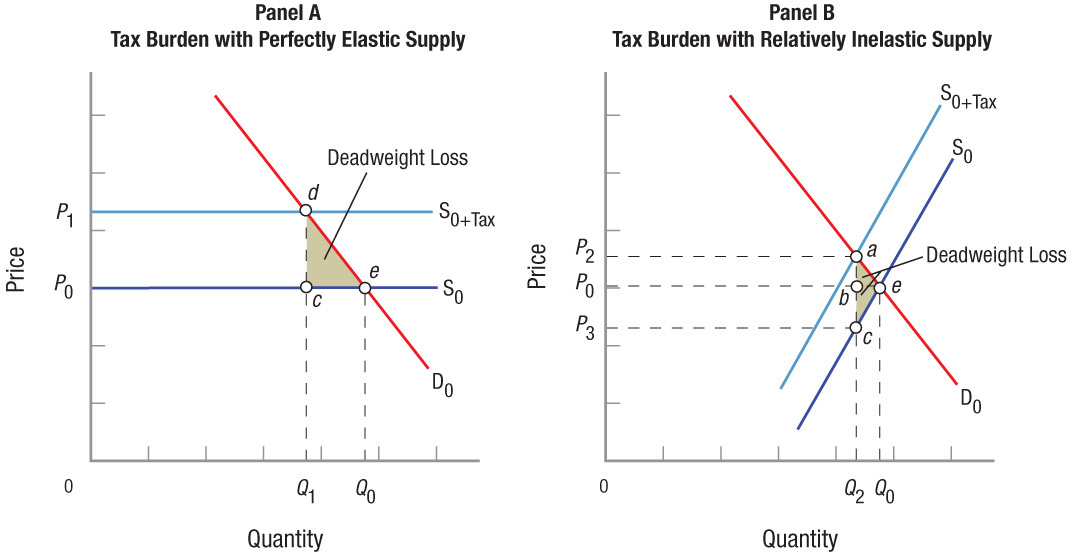

In a similar way, the elasticity of supply is an important determinant of who bears the ultimate burden of taxation. In panel A of Figure 9, demand is held constant at D0 and equilibrium is initially at point e. Supply curve S0 is perfectly elastic, or horizontal. When a per unit tax is added to the product, supply shifts vertically to S0+Tax and the new market equilibrium moves to point d, with Q1 units sold at price P1. Notice that in this limiting situation of perfectly elastic supply, the full monetary burden of the tax (P1 − P0) is borne by consumers in the form of higher prices, although industry bears an indirect burden of reduced output and employment. The deadweight loss, area cde, is relatively large with elastically supplied products.

FIGURE 9

Tax Burden and Supply Elasticities When supply curve S0 is perfectly elastic as shown in panel A, a per unit excise tax added to the product shifts supply vertically to S0+Tax. In this limiting case of perfectly elastic supply, the full burden of the tax (P1 − P0) is borne by consumers through higher prices. The deadweight loss is relatively large with elastic supply curves and equal to area cde. When supply is inelastic as in panel B, with the same excise tax (ac in panel B = cd in panel A), price increases are less, and the reduction in output is also less than before. Consumers pay only part of the tax, ab, and the deadweight loss to society is equal to area cae, less than with the elastic supply shown in panel A.

Now consider the case in which the supply curve is inelastic, as with S0 in panel B of Figure 9. When we add the same tax as before to this supply curve, market equilibrium moves to point a. Price increases less than before (P2 in panel B is lower than P1 in panel A) and the reduction in output is also less than before (Q0 − Q2 in panel B is less than Q0 − Q1 in panel A). Consumers pay only part of the tax, ab, while sellers must absorb bc, and the deadweight loss cae is relatively small.

122

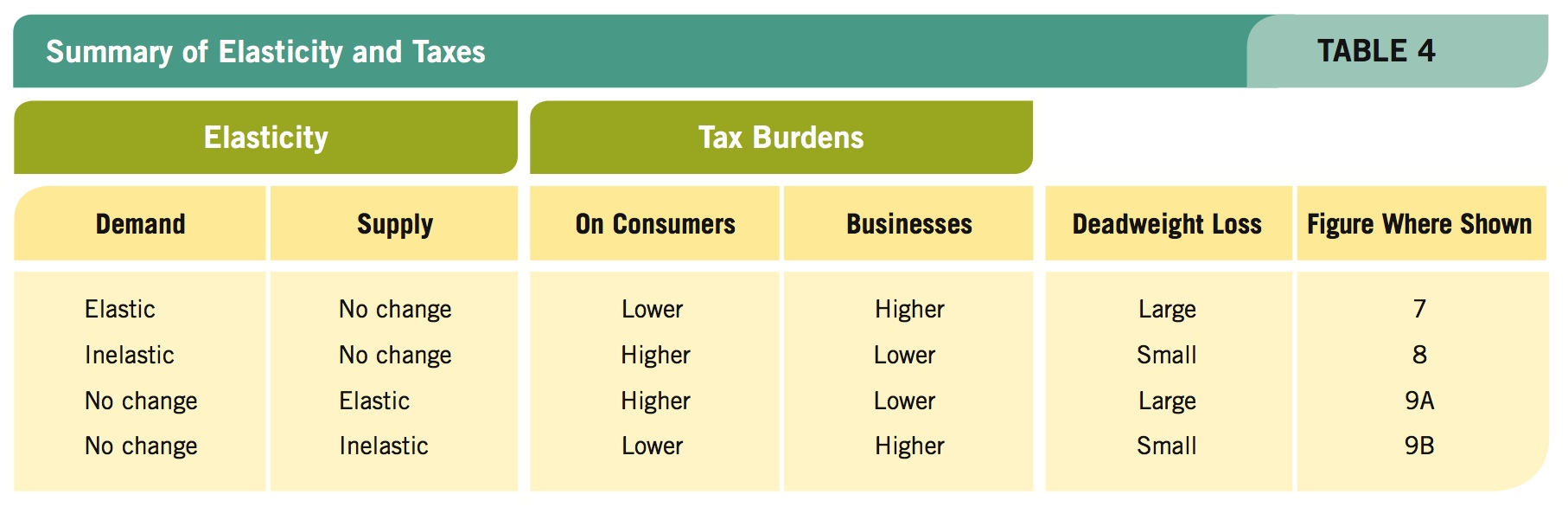

Note what happens in all of these tax cases. Figures 7 to 9 show that whenever a tax is added, the tax moves the market away from its equilibrium point, regardless of whether the tax is borne by consumers, producers, or both. All taxes generate a tax wedge, resulting in a deadweight loss to society. The more elastic the demand or supply, the greater this deadweight loss. Table 4 summarizes these general results.

Are Sales Taxes Fair to Low-Income Households?

With few exceptions, sales taxes are added to the price of nearly everything we buy. Sales taxes vary by state, and can also vary by cities or counties within states. Unlike income taxes, for which the tax rate changes as income rises, sales taxes are a fixed percentage of one’s total purchase. For example, in the state of New Jersey, with a sales tax rate of 7%, you would pay $3.50 in sales tax if you bought a watch that sells for $50. Because of this fixed percentage, sales taxes are often referred to as a That (or proportional) tax, because the tax rate remains constant regardless of the amount purchased. But is this an accurate depiction of the economic burden of sales taxes?

Many economists argue that sales taxes are regressive in nature, meaning that households with lower incomes pay a greater share of their income in sales taxes than households with higher incomes. Such claims have led some economists to vehemently oppose legislation that proposes higher sales taxes as a way to increase state tax revenues.

To measure the burden of sales taxes, one must first analyze how households spend their money. For example, a household earning $25,000 a year spends approximately $5,500 on items subject to the sales tax. These expenditures include most goods (except groceries in many states), car payments, and many services. Major items not subjected to sales taxes include rent and mortgage payments, tuition payments, and most financial instruments. Using an average sales tax rate of 7%, this household would spend $385 a year on sales taxes, or 1.54% of total income. A household earning $100,000 a year, however, spends approximately $18,000 on taxable items. This amounts to $1,260 a year in sales tax, or 1.26% of total income. Therefore, sales taxes are regressive.

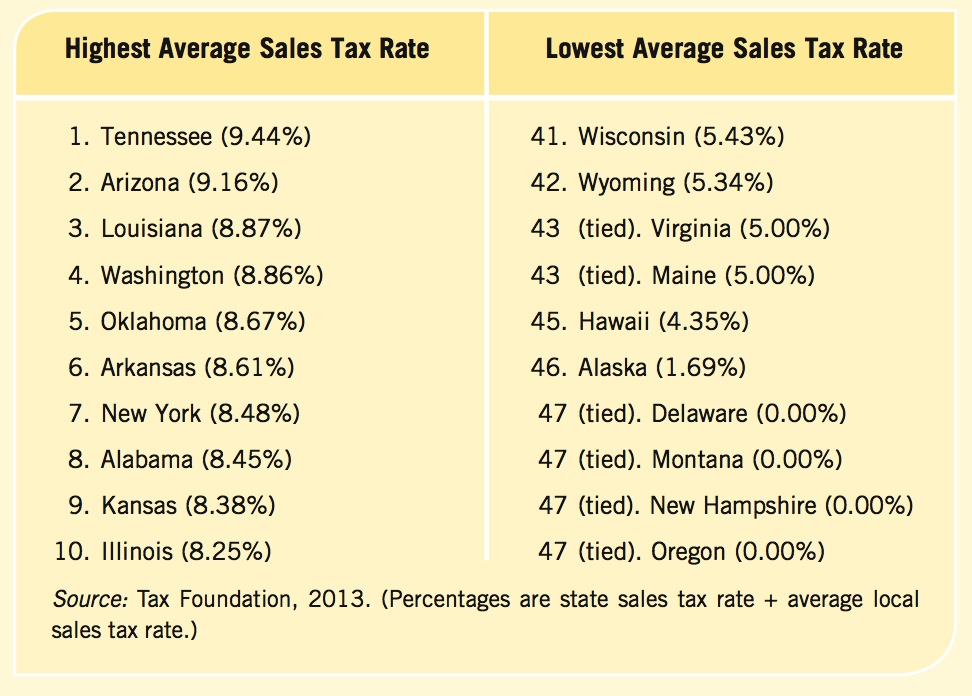

How do states compare in terms of the average sales tax rate? The following table shows the ten states with the highest average sales tax rate and the ten states with the lowest. Surprisingly, a number of states with the highest sales tax rates are those with lower average incomes, such as Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Alabama. This creates a double whammy—income tends to be lower in these states, and being poor takes an even greater toll with high sales taxes.

In sum, when municipalities and states need to raise revenue, the sales tax is the type of tax that hurts the poor the most. Therefore, a few states have opted not to use sales taxes at all, and instead rely on state income taxes, corporate taxes, or property taxes that are progressive, meaning that those with higher incomes pay a greater percentage in taxes. But for most states, sales taxes remain an important source of revenues.

123

These last three chapters have given us the powerful tools of supply and demand analysis. Elasticity is important because it encapsulates the complex relationships among prices, quantity demanded, and total revenues in just two words: elastic and inelastic. When demands are inelastic and some incident marginally reduces supply, policymakers (and now you) know that price will go up substantially, although consumers will continue to purchase the product. Again, this is what happens when gasoline prices rise—consumers continue to purchase roughly the same amount as before, thus oil industry revenue and profits rise substantially in the short run.

If, however, demand is elastic and the same incident reduces supply, prices will rise, but by a smaller amount, and output and employment will fall a lot more. If weather conditions in California and Florida ruin the orange crop, reducing the supply and increasing the price of orange juice, consumers will readily substitute other juices. As a result, output, employment, revenues, and profits will decline in the orange industry.

TAXES AND ELASTICITY

- Taxes on income can be progressive, flat, or regressive based on the percentage of income that becomes taxes. Most income taxes are progressive, but certain forms of That and regressive taxes exist.

- When price elasticity of demand is elastic, consumers bear a smaller burden of taxes while more is borne by sellers. When demands are inelastic, a higher share of the total tax burden is shifted to consumers.

- When the price elasticity of supply is elastic, buyers bear a larger burden of taxes. Elastic supplies also lead to a larger deadweight loss. When supply is inelastic, more of the tax burden is shifted to sellers, but the deadweight loss is lower.

QUESTION: Excise taxes were the principal taxes levied in the United States for the first 100 years or so after the Revolutionary War. Today, excise taxes fall mainly on cigarettes, liquor, luxury cars and boats, telephones, gasoline, diesel fuel, aviation fuel, gas-guzzling vehicles, and vaccines. What do all of these products seem to have in common?

They all appear to have relatively inelastic demands. This reduces the impact of taxes on the industries and leads to higher tax revenues.

124