Chapter Introduction

131

132

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Use a budget line to determine the constraints on consumer choices.

- Determine how budget lines change when prices or income changes.

- Describe the difference between total and marginal utility.

- Describe the law of diminishing marginal utility.

- Use marginal utility analysis to derive demand curves.

- Explain why individuals sometimes make irrational decisions in predictable ways.

- Describe five psychological factors that influence economic decision making.

Each day, virtually every person makes consumption choices, whether that means going to the mall to buy a new outfit, to a restaurant to dine with friends, or to the supermarket to stock up on groceries for the week. The consumption choices that people make form what we have described as demand. But how do consumers make these choices? One of the important lessons from prior chapters is that individuals aim to maximize their well-being given a limited amount of resources.

In order to make consumption choices, individuals must first determine what is afford-able; in other words, what choices of goods and services one’s budget can afford. Although we naturally think of income as the primary determinant of what can be afforded, prices also play a key role. Think of how a sale at a department store increases the amount of goods we can buy, or how higher gas prices restrict what we can spend on other goods. Once we know what we can afford, the next question is then how to allocate budgets to maximize our well-being.

The process by which individuals choose goods and services to maximize their overall happiness can be tricky to analyze. The main reason is that demand analysis rests on an important assumption: People are rational decision makers. Do people always act rationally? Of course not. You might spend more money at an expensive restaurant than you had wanted because your friends convinced you to go, which then caused you to give up buying an outfit on sale that would have given you more satisfaction. In these situations, individuals often come to realize that money is not always spent in the optimal manner; if it were, we would never regret the spontaneous purchases we make.

The fact that individuals sometimes make irrational decisions makes the analysis of consumer choice difficult to predict. However, a number of economists, called behavioralists, have been studying certain situations in which people make irrational decisions. What these economists have found is that although the decisions we make may sometimes appear irrational, they are irrational in predictable ways. For example, having paid a nonrefundable deposit on a wedding dress, a bride is more likely to purchase the dress even if her preferences change, because she had already committed to part of the purchase. Or, a person attempting to start a diet program may purchase a long-term plan given an optimistic anticipation of completing the program, only to give up after a few months. These examples illustrate how psychological factors influence our consumption choices in ways that lead to decisions economists would view as irrational.

Important though this work on the irrational is, it does not invalidate the assumption that people choose rationally. If there were a preponderance of irrationality, society would come to a halt because we could not predict anything. What pedestrian would cross the street even if the light said “walk” if there was a modicum of fear that many drivers would act irrationally and ignore a red light? People do miss or ignore red lights, but not often.

So we are left with an underlying assumption of rational decision making that is not bedrock, but is reasonable and powerful nonetheless. In this chapter, we are going to see what lies behind demand curves by looking at how consumers choose. In the next chapter, we will examine what lies behind supply curves by looking at how producers choose to produce what they do.

There are two major ways to approach consumer choice. The first theory explaining what people choose to buy, given their limited incomes, is known as utility theory or utilitarianism, and owes its roots to the work of 18th century philosopher Jeremy Bentham. This theory holds that rational consumers will allocate their limited incomes so as to maximize their happiness or satisfaction.

The second approach, indifference curve analysis, is covered in the Appendix. Developed by Francis Ysidro Edgeworth in the late 19th century, it added analytical rigor to utility analysis by developing indifference curves, which portray combinations of two goods of equal total utility. Edgeworth, a shy man who studied in public libraries because he saw material possessions as a burden, brought the precision of mathematics to bear on utility theory.

133

How Do We Decide What to Buy?

Each day, we make economic decisions on what to buy, what to eat, and how to allocate our limited time. Although marginal utility analysis can guide us into making rational decisions, behavioral economic factors play an important role as well.

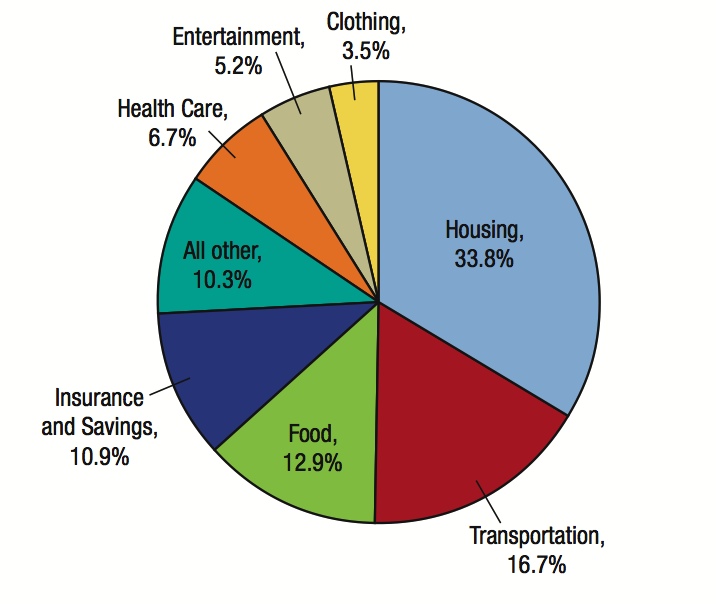

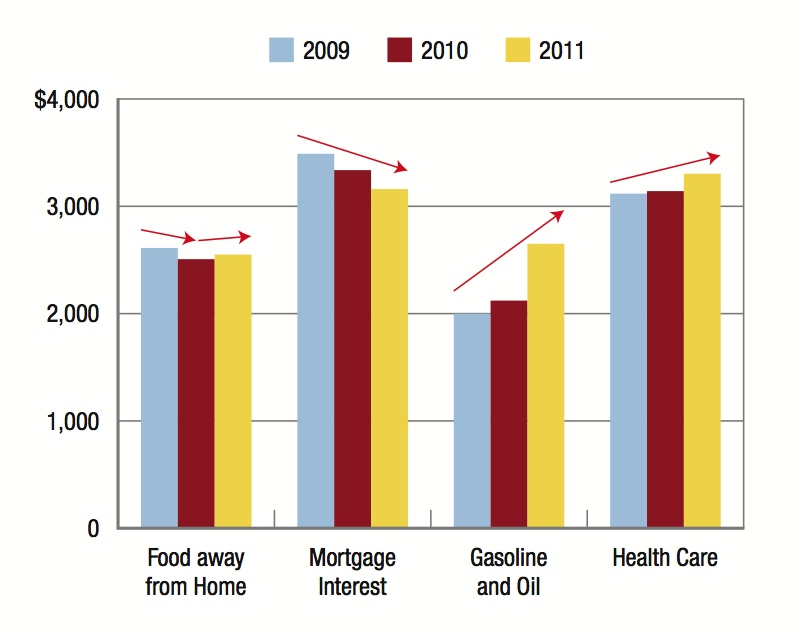

The average distribution of U.S. household budgets on various expenditure components in 2011, along with trends in selected components from 2009 to 2011.

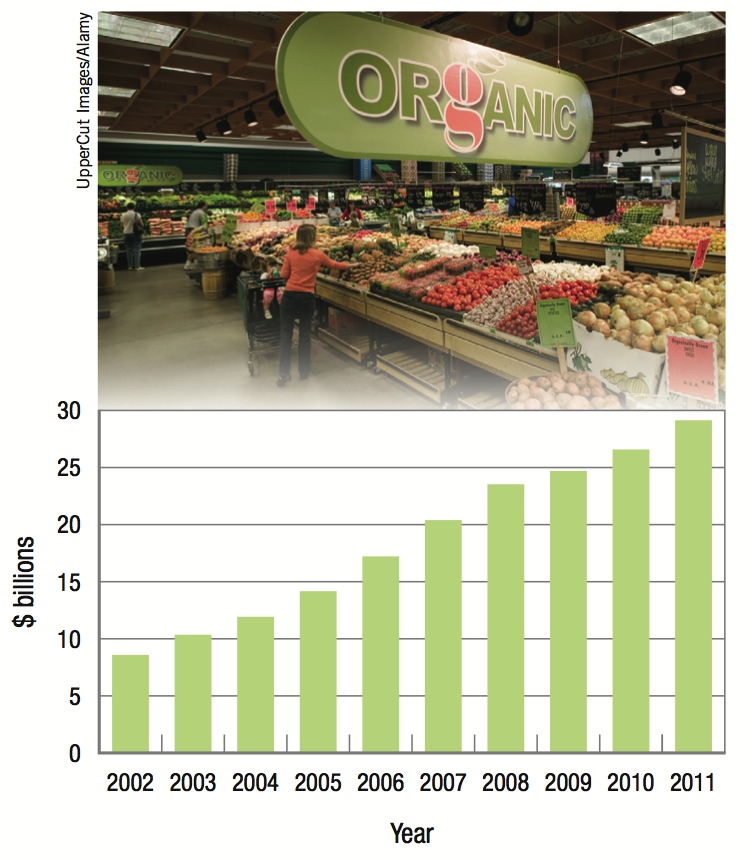

As preferences for organic foods increase, more supermarket chains respond, leading to rising sales of organic foods.

Player jerseys represent the largest component of the $3 billion annual NBA product market. The top selling jerseys in the 2011–2012 season were:

- Derrick Rose, Chicago Bulls

- Jeremy Lin, New York Knicks

- Kobe Bryant, Los Angeles Lakers

- LeBron James, Miami Heat

- Carmelo Anthony, New York Knicks

134