Behavioral Economics

behavioral economics The study of how human psychology enters into economic behavior as a way to explain why individuals sometimes act in predictable ways counter to economic models.

Up to this point, we generally have assumed that individuals make rational decisions that maximize their well-being. Yet, an increasing number of economists have devoted their attention to studying situations in which individuals do not appear to follow rational economic thinking, at least the behavior that economic models predict will result. This section turns our attention to the study of behavioral economics. Behavioral economics is the study of how human psychology enters into economic behavior as a way to explain why individuals sometimes act counter to how economic models predict.

145

All individuals from time to time make irrational decisions; that is part of human nature. An important point to keep in mind is that we are not analyzing random behavior. Instead, behavioral economics looks at situations in which people act irrationally in predictable ways. This could be a big deal because it challenges the notion of economic rationality that we have assumed in our models. The fact that irrational behavior can occur in predictable ways means that clever people try to take advantage of this behavior. What psychological factors influence irrational behavior, and how do these factors translate into clever opportunism?

This section presents five important psychological factors influencing economic behavior: (1) sunk cost fallacy, (2) framing bias, (3) overconfidence, (4) overvaluing the present relative to the future, and (5) altruism. Each of these factors influences decisions we make every day. In fact, marketers of goods and services often exploit these factors in order to attract consumers to make purchases they otherwise might not make. Let’s look at each factor and some common examples illustrating each concept.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

sunk cost A cost that has been paid and cannot be recovered; therefore, it should not enter into decision making affecting the present or future.

Suppose a few months ago you had paid a nonrefundable registration fee of $200 to attend your favorite annual collector’s convention in town to be held this weekend. The fee is not refundable or transferable to another person. Therefore, the $200 fee you paid is a sunk cost, a cost that has been paid and cannot be recovered. As the weekend approaches, you realize that you are extremely behind in your studies, so much so that going to the convention would likely take away the last bit of time to prepare for upcoming midterm exams.

sunk cost fallacy Occurs when people make decisions based on how much was already spent rather than how the decision might affect their current well-being.

You think to yourself, “If I would have known I’d be so busy with school, I wouldn’t have paid $200 to register for the convention. But since I’ve already paid it, I’m certainly not going to let my money go to waste, so I’m going to go despite the potential consequences to my grades.” Does this seem logical?

According to economic theory, it does not. Sunk costs are costs that cannot be undone. Therefore, the decision whether to attend should not hinge upon past payments, because the registration fee has already been paid. By incorporating sunk costs into present and future decisions, a sunk cost fallacy occurs as people make decisions based on how much was already spent rather than how the decision might affect their current well-being. In this case, because going to the convention may have consequences on your grades, the wise decision would be to forgo the convention. Either way, the money is already gone.

The sunk cost fallacy often appears in situations in which people feel that they have invested too much time or money into a project to quit. Another common example is the tuition paid for school, a sunk cost. Often, students who fail the midterm and have little hope of raising their grades are reluctant to withdraw from a class because they are unwilling to give up a class that is already paid for, instead hoping for a miracle (or a sympathetic professor) that the final grade will be a passing one. But often the result is a failing grade, which means not only do they need to retake the class (and pay for it once more), but worse, a failing grade appears on their transcript.

Framing Bias

Does a price of $9.99 seem a lot different from $10.00? It really shouldn’t, given the difference is one-tenth of 1%. Even more startling are prices displayed at most gas stations, which often show prices in tenths of a cent, such as $3.999 (the next time you pass by a gas station, notice the extra nine-tenths of a cent). Compared to $4.00, $3.999 is a difference of just one-fortieth of 1%. Finally, does “Buy One Get One Half-Off” sound like a better deal than “25% off “? It might; however, if you buy two items with the same price, the total cost is the same under each deal.

framing bias Describes when individuals are steered into making one decision over another or are convinced they are receiving a higher value for a product than what was paid for it.

146

In each of the above examples, the percentage difference between the two prices is zero or virtually zero. Yet, consumers tend to react differently to these prices, with the former being interpreted as a lower price than the latter, enough to influence buying decisions. This ability to influence consumer decisions by how prices are displayed is an example of a framing bias, which occurs when individuals are steered toward one choice over another by how those choices are portrayed. Framing techniques are used by marketers to increase sales of products without actually lowering the price.

Framing biases are not limited to pricing strategies. Much in the same way that firms steer consumers toward buying products using prices, a broad range of framing effects can be used to steer individuals toward one political candidate or one political issue over another, toward one product over another in advertising campaigns, and toward one policy over another in legislative debates.

Framing biases also occur when firms convince buyers that what they purchased is worth much more than what they paid. This type of strategy attempts to alter the perceptions of buyers into believing they are always receiving a great deal. Ever notice that some stores perpetually have sales of 10% to 20% off everything, or give money back in the form of gift cards for future visits? Wouldn’t it be the same if a store just marks down the sticker prices of everything? Perhaps, but consumers tend to respond more positively to sales and other seemingly good offers.

Overconfidence

Feeling confident about one’s abilities, attractiveness, or intellectual capacity is a trait often instilled from one’s childhood. No doubt self-esteem plays an important role in the success of many people. But overconfidence in one’s abilities can have the opposite effect.

Watch the auditions of any reality talent show, and notice the pitchy, off-key singers who belt their hearts out as if they were on stage at the Grammy Awards, only to be brought back to reality by the harsh criticism of the judges. Being overconfident can lead to decisions that have consequences, such as picking the wrong stock in which to invest, spending too much time and effort applying to only the very top graduate school or law school, or turning down potential respectable boyfriends or girlfriends in hopes of a dream mate.

Wanting to feel confident about one’s abilities and choices sometimes leads to decisions that run counter to economic theory, and marketers often take advantage of this factor. One- and two-year gym memberships offered for an attractive upfront prepaid price is a great deal for someone eager to lose weight and get in shape. But often such ambitions fall short, leading many gym memberships to go unused (with the money comfortably in the gym’s bank account).

Overvaluing the Present Relative to the Future

It is often difficult to plan for the future. Money saved today can earn interest, and money invested in financial instruments and assets can increase in value over time. Despite the higher value of money in the future, it is still money one must give up using today. Therefore, people sometimes are reluctant to save for the future despite lucrative incentives such as retirement fund matching programs offered by employers.

The same is true for paying off debt. Paying the minimum payment on credit card balances seems easy, but accruing finance charges of 15% or more can put a severe crunch on finances in the future. Although differences in time preferences themselves are not irrational per se, because the future often appears so distant, it can blur the reasoning behind sound economic decisions. For example, a society’s unwillingness to fully tackle climate change results from overvaluing present benefits relative to future costs.

147

Altruism

altruism Actions undertaken merely out of goodwill or generosity.

The last factor to be discussed is altruism, or actions undertaken merely out of goodwill or generosity. Buying a sandwich for a homeless person you will likely not see again, donating money to a charitable organization, or helping a tourist find his or her way to a hotel all are friendly gestures that do not provide any reward except for the positive feeling one gets from helping others.

Tipping and Consumer Behavior

If consumers maximize their utility with a given (limited) budget, why would they ever tip? Consider that tips come at the end of a meal. How can tips affect the quality of service already given?

Many reasons might explain tipping. First, if it is a restaurant you frequent, tips might assure better service in the future. Second, you might consider tips to be rewards for higher quality service. Third, tipping is a custom and is part of the income for several dozen occupations.

What would happen if many people refused or neglected to tip? Would people in various occupations seek to make tipping legally binding? It is likely this would be the result, if a recent case in New York is any guide.

If you have ever gone to a restaurant with a large party, you will notice that menus and bills often state that a set tip will be added for large parties. One large party gave a very small tip after what they considered to be inadequate service. The restaurant sued, claiming that an 18% tip was mandatory. The court’s decision for the tipper turned on the phrasing in the menu. This could be viewed as a first shot: If too many people refuse to tip or tip poorly, we can expect legal redress.

We can establish, then, that tipping is a custom that leads to better service, and so is followed even though the tip comes after the service is performed. In this way, it seems to run counter to the idea of people tipping based on a calculation of marginal utility. And how much we tip raises questions about how we calculate marginal utility.

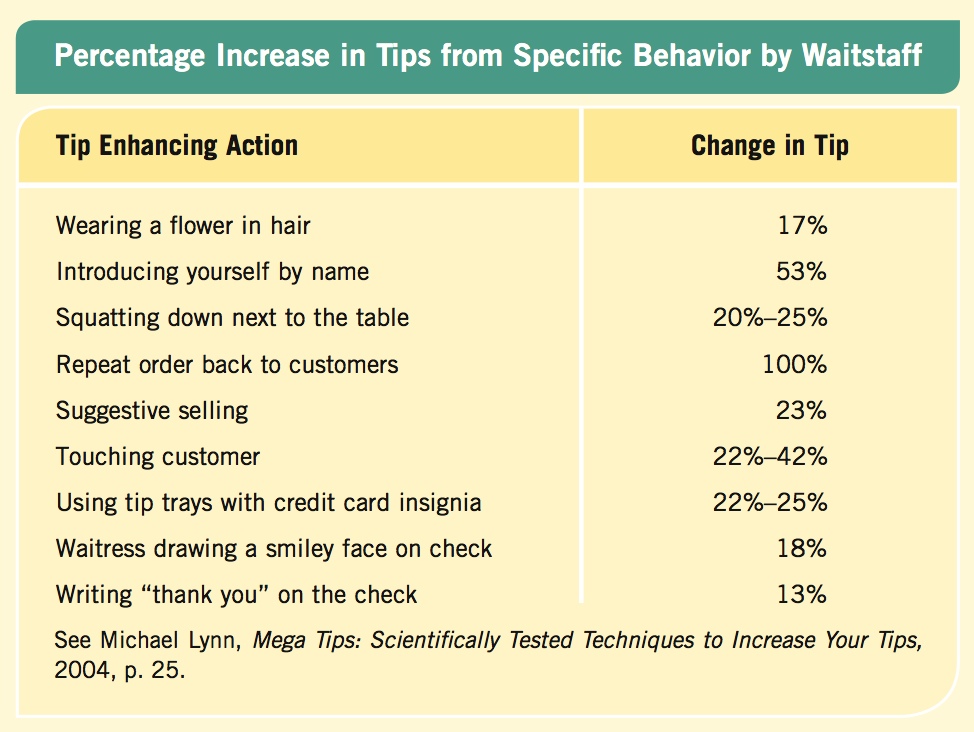

Economists have found only a weak statistical link between quality of service and size of the tip. Tipping also appears to be unrelated to the number of courses in the meal, and whether or not people intend to return to the restaurant. The accompanying table shows some of the things that do affect the size of the tip.

Obviously, a waiter or waitress cannot do all of these things and expect to see tips increase by the sum of all the percentages, but we all have experienced many of these techniques in restaurants. Interestingly, if a waitress draws a smiley face on the bill, her tips go up, but if a waiter does the same, his tips go down. Suggestive selling raises the tip because people tend to tip based on the size of the bill. After having read about this study, you probably will find yourself being a little cynical when some of these techniques are used the next time you dine out.

Source: Based on Raj Persaud, “What’s the tipping point?” Financial Times, April 9, 2005, p. w3.

148

Thus, altruistic behavior provides utility in the sense of feeling good about one’s actions, even though the actions may cost money, time, and effort, resources that will reduce one’s ability to consume other items. Although altruism is generally not viewed as a mistake, it nonetheless represents a limitation of the rational choice model. And because altruistic behavior is so commonplace (such as the generosity of individuals in times of natural disasters, both within the country and abroad), economic models need to account for the utility gained from being generous. Yet, such feelings of goodwill are difficult to measure in economic models, which makes it a factor left to behavioral economists to take into account.

Each of the five factors described in this section add to the discussion in the previous section that marginal utility analysis does not capture all circumstances of individual economic behavior. But it is important to note that these limitations and the behavioral factors are the exceptions to the rule; marginal utility analysis still plays an important role in how we live our daily lives.

Recognizing the validity of these criticisms, economists have tried to limit themselves to working with the sorts of data they can collect, in this case purchases by individuals. By formulating hypotheses about what consumers purchase and what this says about their preferences, economists have managed to develop a theory of consumer behavior that does not require that utility be measured. This more modern approach to analyzing consumer behavior that reaches the same conclusions as marginal utility theory is known as indifference curve analysis. Because indifference curve analysis extends the discussion of consumer behavior beyond the principles of consumer choice, it is discussed in the Appendix.

BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS

- Behavioral economics involves incorporating human psychology into economic decision making to explain why individuals sometimes do not act according to what economic models predict.

- Behavioral economics studies predictable deviations from rational behavior.

- The sunk cost fallacy is a common mistake when individuals feel obligated to take sunk cost expenditures into account when making present and future decisions.

- Framing biases occur when marketers present prices in a way that makes them appear lower than what they actually are.

- Overconfidence, overvaluing the present relative to the future, and altruistic actions are other factors influencing economic behavior.

QUESTION: A common practice in some supermarkets is to hang signs in the soup section that read “limit 12 per customer.” Would our previous economic models predict that consumer behavior would change at all? How about behavioral economics? If it did, what deviation would this be?

According to marginal utility analysis, putting up a sign indicating a limit of 12 cans of soup per customer should not affect buying behavior, unless the shopper actually planned to buy more than 12 cans, in which case the sign puts a restriction on the purchase. However, in behavioral economics, putting up this sign represents a framing technique: by putting a limit of 12 cans, the supermarket is implying that the soup is so good that customers have a habit of buying large quantities (which may not be likely at all). By suggesting the soup is “popular,” it draws customers into buying the soup that they otherwise might overlook, creating a framing bias.

149