Chapter Summary

Chapter Summary

Section 1: Monopoly Markets

A monopoly is a one-firm industry with no close product substitutes and with substantial barriers to entry.

Types of Barriers to Entry

Control over a significant factor of production: occurs when a company owns a significant share of its key ingredient or input in production

Economies of scale: occurs when firms must incur large fixed costs before production can begin

Government protection: patents and copyrights that provide an exclusive right to sell a product

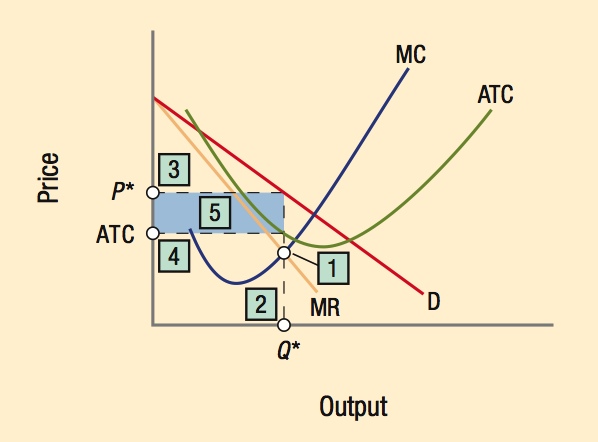

5 Steps to Maximizing Profits for a Monopolist:

- Find MR = MC

- Find optimal quantity where MR = MC

- Find optimal price where quantity meets the demand curve

- Find average total cost at the optimal Q

- Find the profit = Q × (P − ATC)

The firm’s demand and supply curve is the same as the industry’s demand and supply curve.

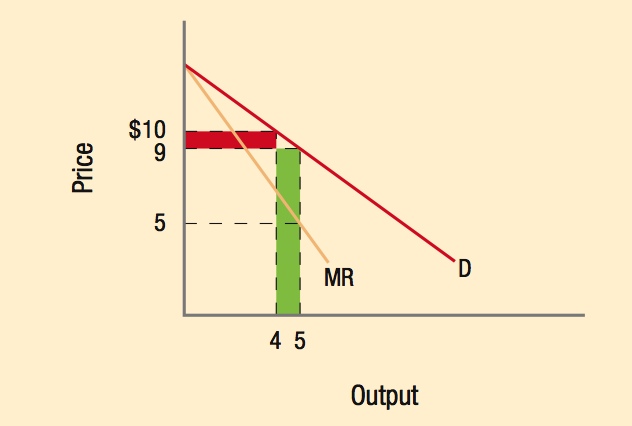

Marginal revenue is less than price for a monopoly: If a firm can sell 4 units at $10 but must drop price to $9 to sell 5 units, marginal revenue equals $5 because the seller loses a dollar from each of the previous 4 units (red area) but gains $9 from the sale (green area).

Just because a monopolist has no competitors doesn’t mean it always earns profits. Think of late-night infomercials selling, at times, bizarre products. Some are successful but others fail.

Mop slippers were a unique invention that really never took off. Not all monopolies are profitable.

Section 2: Comparing Monopoly and Competition

In a monopoly market, output is lower and price is higher compared to a competitive market due to the lack of competitors to the monopoly firm.

A firm with market power is more likely to engage in rent-seeking behavior (spending resources to protect market power) and x-inefficiency (wasting resources because competition doesn’t exist).

Without competition from another football league, the NFL likely produces fewer games and charges higher prices than it would in a competitive market.

239

Section 3: Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is charging different prices for the same product in the attempt to grab more surplus from consumers.

Conditions for Price Discrimination to Work Best

- Firm must have market power (i.e., cannot be a price taker).

- Market can be segmented into different consumer groups.

- Seller must be able to prevent arbitrage.

Three Forms of Price Discrimination

Perfect (first-degree) price discrimination: Seller charges exactly what consumers are willing to pay, and extracts all consumer surplus.

Second-degree price discrimination: Prices differ based on the quantity being purchased.

Third-degree price discrimination: Prices differ based on consumer characteristics, such as age (e.g., kids and senior discounts), status (e.g., student or military discounts), or flexibility (e.g., airline pricing).

Section 4: Regulation and Antitrust

A natural monopoly has large economies of scale such that one firm is more efficient than multiple firms. The profit maximizing point occurs where MC (and ATC) is falling. To prevent exploitation of market power, natural monopolies are often regulated.

Besides economies of scale, most people prefer just one electric company as a monopolist, rather than multiple electric companies each with its own power lines.

Antitrust laws are designed to promote competition and prevent monopolies from developing.

Two Major Antitrust Laws

Sherman Act of 1890: outlawed trusts and cartels—restraint of trade and monopolization.

Clayton Act of 1914: outlawed some forms of price discrimination and mergers that would significantly reduce competition.

Ways to Measure Market Power

Concentration ratios: adding up the market shares of the 4 or 8 largest firms in an industry, and ranges from 0 to 100.

HHI index: sum of the square of market shares of all firms in an industry, and ranges from 0 (perfect competition) to 10,000 (monopoly). HHI values over 1,800 are concentrated industries where mergers are likely to be challenged.

A contestable market looks like a monopoly but does not act like one because the threat of entry keeps prices low. Low-fare airlines that serve unique routes still offer low prices if they fear new entrants.

240