Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Game Theory

10

Learning Objectives

10.1 Describe product differentiation and its impact on the firm’s demand curve, and how it determines the market power that a monopolistically competitive firm can exercise.

10.2 Compare pricing and output decisions for monopolistically competitive firms in the short run and long run, and explain why firms earn only normal profits in the long run.

10.3 Describe cartels and the reasons for their instability.

10.4 Explain the kinked demand curve model and why prices can be relatively stable in oligopoly industries.

10.5 Describe the basic components of a game and explain the difference between simultaneous-

10.6 Solve for Nash equilibria using a best-

10.7 Recognize why Prisoner’s Dilemma outcomes occur and provide real-

10.8 Explain how firms can overcome the Prisoner’s Dilemma using cooperative strategies and repeated actions.

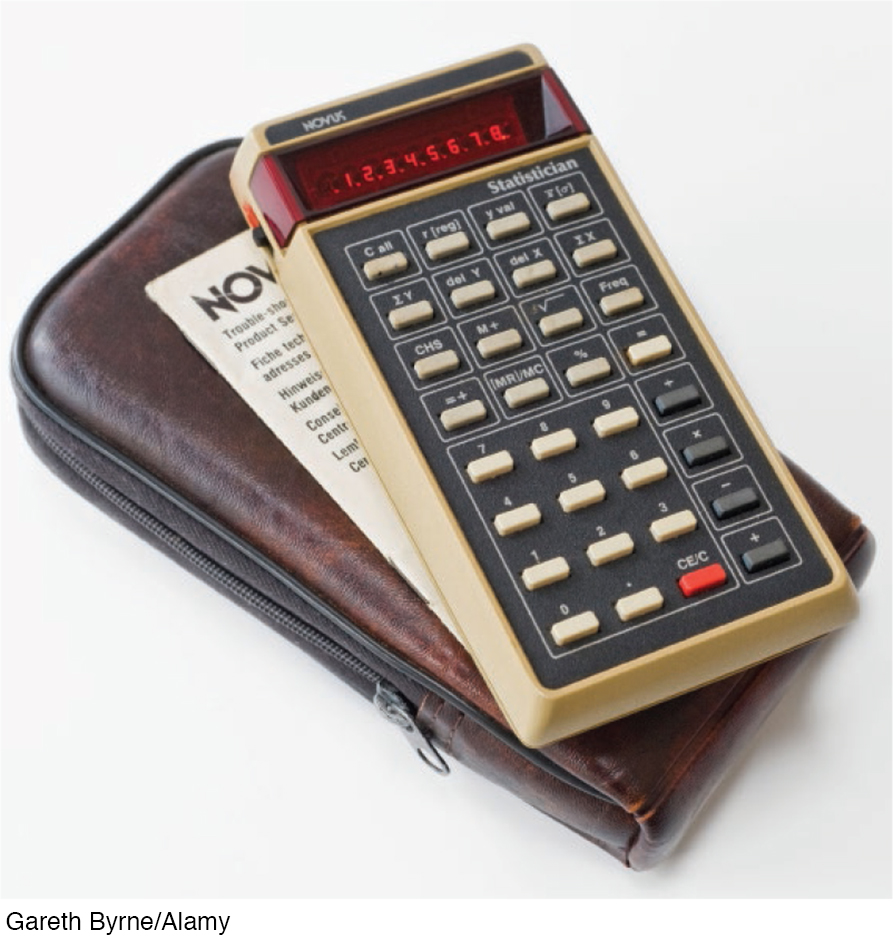

Home computing made its debut in the early 1980s. At that time, a basic computer with a single-

The previous two chapters studied perfect competition and monopoly, which are at the opposing extremes of market structures we typically see. Perfect competition assumes a homogeneous (identical) good produced by many firms, while a monopoly assumes a unique good produced by just one firm. In reality, over 90% of the goods and services we consume do not fall into either category. Most of the goods and services we consume are competitive in nature but are also differentiated (or branded) in some way.

Suppose you want a quick burger for lunch. Your choices include McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, Five Guys, and many other burger joints located in your town. The market for burgers is clearly not a monopoly. Yet, given the variety of burgers from which to choose, it’s not pure competition either, unless you think that all burgers are the same—

These pressures limit the market power that can be exercised by monopolistically competitive and oligopolistic firms. We saw in the previous chapter that monopolies have the most market power, which is the ability to set price (and get away with it). We contrasted this with perfectly competitive firms, which are price takers: They have no ability to set price. In this chapter, we will see that monopolistically competitive firms have a very limited amount of market power. Oligopolies have more market power, but less than monopolies.

While market power is a downside of monopolistic competition and oligopoly, competitive pressures on them can result in benefits to all. Firms are constantly looking for ways to make their products better (to increase their value) or less expensive to produce. In doing so, a number of important changes in the competitive global market have appeared:

Increase in technological development

Increase in variety of goods and services

Reduction in the price of inputs and resources (with economies of scale or offshoring production)

Reduction in transportation costs

Reduction in trade barriers

Recall that when supply increases (shifts to the right), the market price falls and the market quantity rises. For each of the factors listed previously, a corresponding increase in supply results, helping to explain why this year’s computers and smartphones cost less than in previous years—

The key to understanding monopolistic competition is product differentiation, as we saw in the burger example, and the key to understanding oligopolies is interdependence. By interdependence, economists mean that pricing and other decisions have to be made by considering what other firms might do. If Delta Airlines raises its prices, will United and American follow suit, or will they freeze their prices hoping to lure Delta customers away?

To best explain interdependence, the chapter concludes by studying game theory, a modern way to examine strategy and competition. Although game theory was initially developed to analyze the behavior of interdependent oligopolistic firms, it has countless uses and applications in our daily lives. We will touch on a few of these many uses so that you can see the richness of taking a game theory approach.