MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION

Until the 1920s, competition and monopoly were the only models of market structure that economists had in their toolbox. As consumerism expanded and more varieties of goods and services became available, economists found that these two models were inadequate to explain the vast markets for many goods. In other words, some markets were considered imperfect, or not fitting the mold of the traditional competitive structure. This led to the study of imperfect markets, which included monopolistic competition and oligopoly.

monopolistic competition A market structure with a large number of firms producing differentiated products. This differentiation is either real or imagined by consumers and involves innovations, advertising, location, or other ways of making one firm’s product different from that of its competitors.

Monopolistic competition is nearer to the competitive end of the spectrum and is defined by the following characteristics:

A large number of small firms. Similar to perfect competition, each firm has a very small share of the overall market. Because no one firm can appreciably affect the market, most ignore the reactions of rival firms.

Entry and exit are easy.

Unlike perfect competition, products are different. Each firm produces a product that is different from its competitors or is perceived to be different by consumers. What distinguishes monopolistic competition from perfectly competitive markets is product differentiation.

Product Differentiation and the Firm’s Demand Curve

Most firms sell products that are in some way differentiated from their competitors. For example, this differentiation can take the form of a superior location. Your local dry cleaner, restaurant, grocery, and gas station can have slightly higher prices, but you will not abandon them altogether. Other companies have branded products that give them some ability to increase price without losing all of their customers, as would happen under perfect competition.

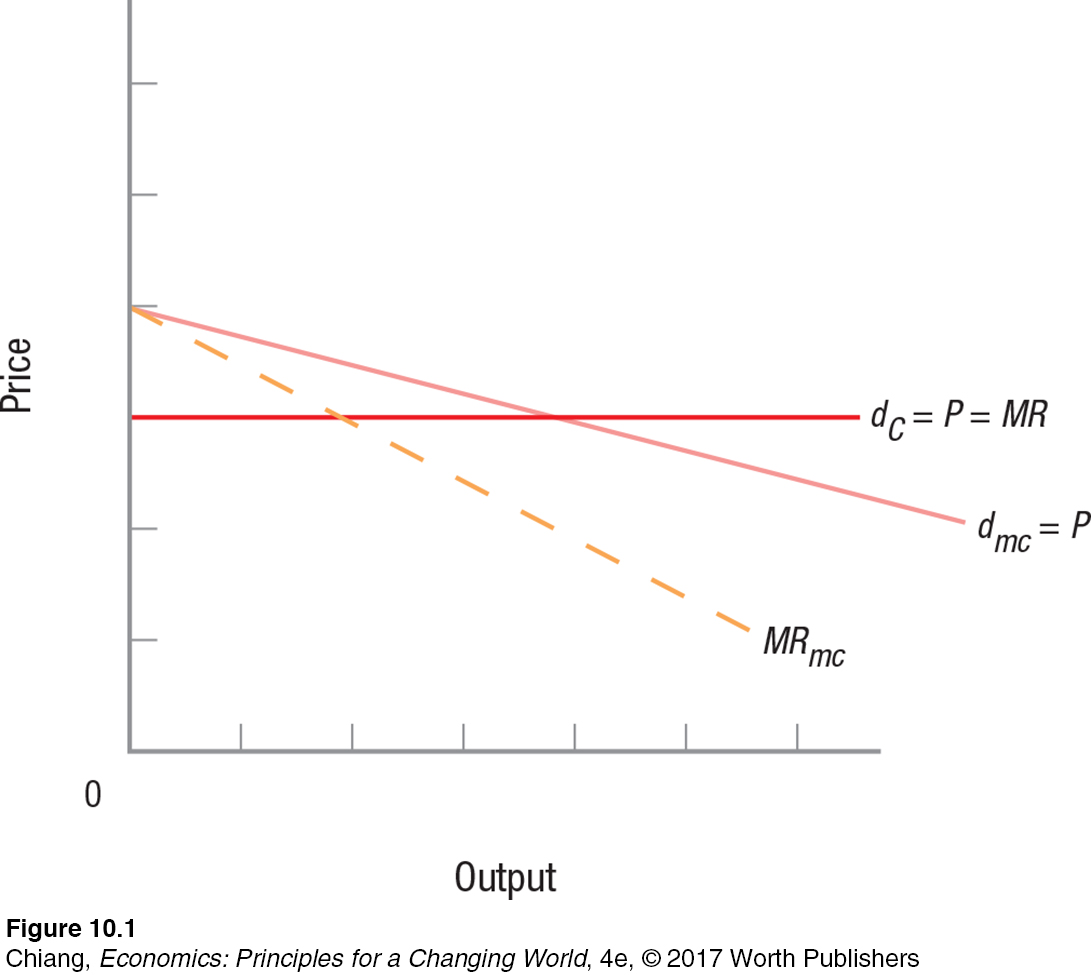

Product differentiation gives the firm some (however modest) control over price (market power). This is illustrated in Figure 1. Curve dc is the competitive demand curve, and dmc is the demand curve faced by a monopolistic competitor. This is similar to the monopolist’s demand, but the demand curve is considerably more elastic. Because a monopolistic competitor is small relative to the market, there are still a lot of substitutes. Thus, any increase in price is accompanied by a substantial decrease in output demanded. But unlike the perfectly competitive firm that faces a horizontal demand curve with no power to raise price, a monopolistically competitive firm has some market power with its slightly less elastic demand curve.

Like a monopolist, the monopolistically competitive firm faces a downward-

product differentiation One firm’s product is distinguished from another’s through advertising, innovation, location, and so on.

Product differentiation can be the result of a superior product, a better location, superior service, clever packaging, or advertising. All of these factors are intended to increase demand or reduce the elasticity of demand and generate loyalty to the product or service. Therefore, the demand curve for monopolistically competitive firms can vary. Although demand curves tend to be elastic (flat), firms that are able to successfully differentiate their products can achieve greater market power, which makes their demand curves steeper, allowing them to charge higher prices.

The Role of Advertising An important way to differentiate products is through advertising. Economists generally classify advertising in two ways: informational and persuasive. The informational aspects of advertising let consumers know about products and reduce search costs. Advertising is a relatively inexpensive way to let customers know about the quality and price of a company’s products. It can also enhance competition by making consumers aware of substitute products. Advertising also has the potential to reduce average costs by increasing sales, bringing about economies of scale.

But advertising does have a negative side as well. Because so much of advertising is persuasive (ads containing little informational content, but designed to shift buyers to competitors producing similar products), the result is that the cost of advertising drives up the price of many products. With all the advertising we see, a significant portion probably cancels each other out.

Advertising is another area in which technology has transformed the medium: Digital video recorders permit ad-

All of these ways to differentiate their products give monopolistically competitive firms some control over price. This market power means that their profit-

ISSUE

Do Brands Really Represent Pricing Power?

What is a brand? All of us know brands through their names and logos. Nike has the swoosh, Intel has a logo and the four-

Brand names start with the company that makes the product or provides the service. In the past, this meant that brand names came from a limited number of sources. Some companies were named after their founders, such as Walt Disney; some companies were named after what they supplied, such as IBM (International Business Machines); and some have also been named by their main product, such as the Coca-

Whatever their origins, these brands have recognizable brand names, and they command price premiums. According to the annual BrandZ study by Millward Brown, Apple was the most valuable brand in 2015, valued at nearly $247 billion, followed by Google, Microsoft, IBM, and Visa. The top ten brands were all American, though Chinese brands Tencent, Alibaba, and China Mobile came in at 11th, 13th, and 15th, respectively. In fact, Chinese brands are the fastest growing in the world, as China’s economy continues to transform to include major high-

Market power is what companies want. It allows companies to charge more for goods that are similar to those of lesser-

Sources: BrandZ Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brands 2015, Millward Brown, WPP Companies.

Price and Output Under Monopolistic Competition

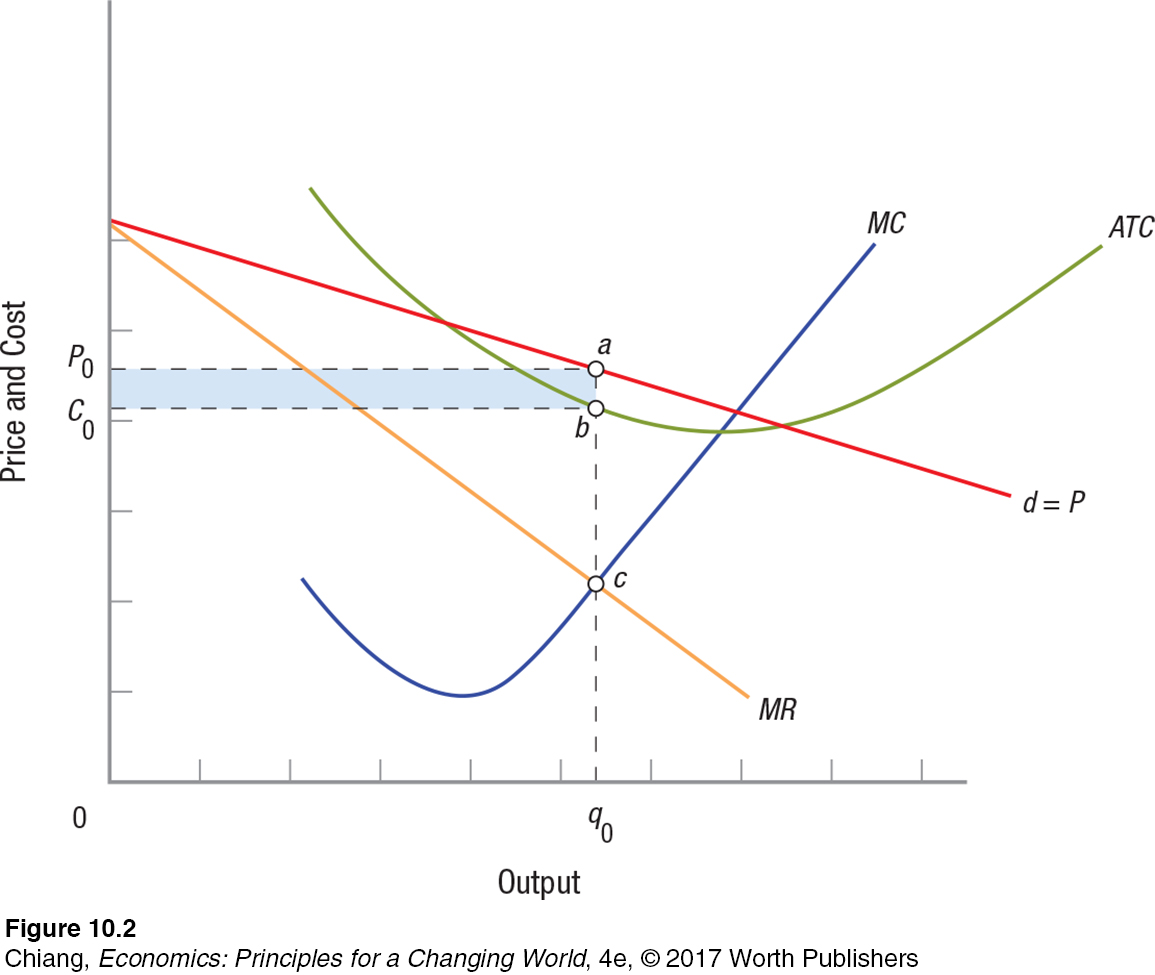

Profit maximization in the short run for the monopolistically competitive firm is a lot like that for a monopolist, but given the competition against firms with similar products, profit will tend to be less. Short-

This does not mean that profits are trivial. Many huge global firms sell their products in even larger global markets, and their profits are significant. They are large firms, but do not have significant market power. Many companies—

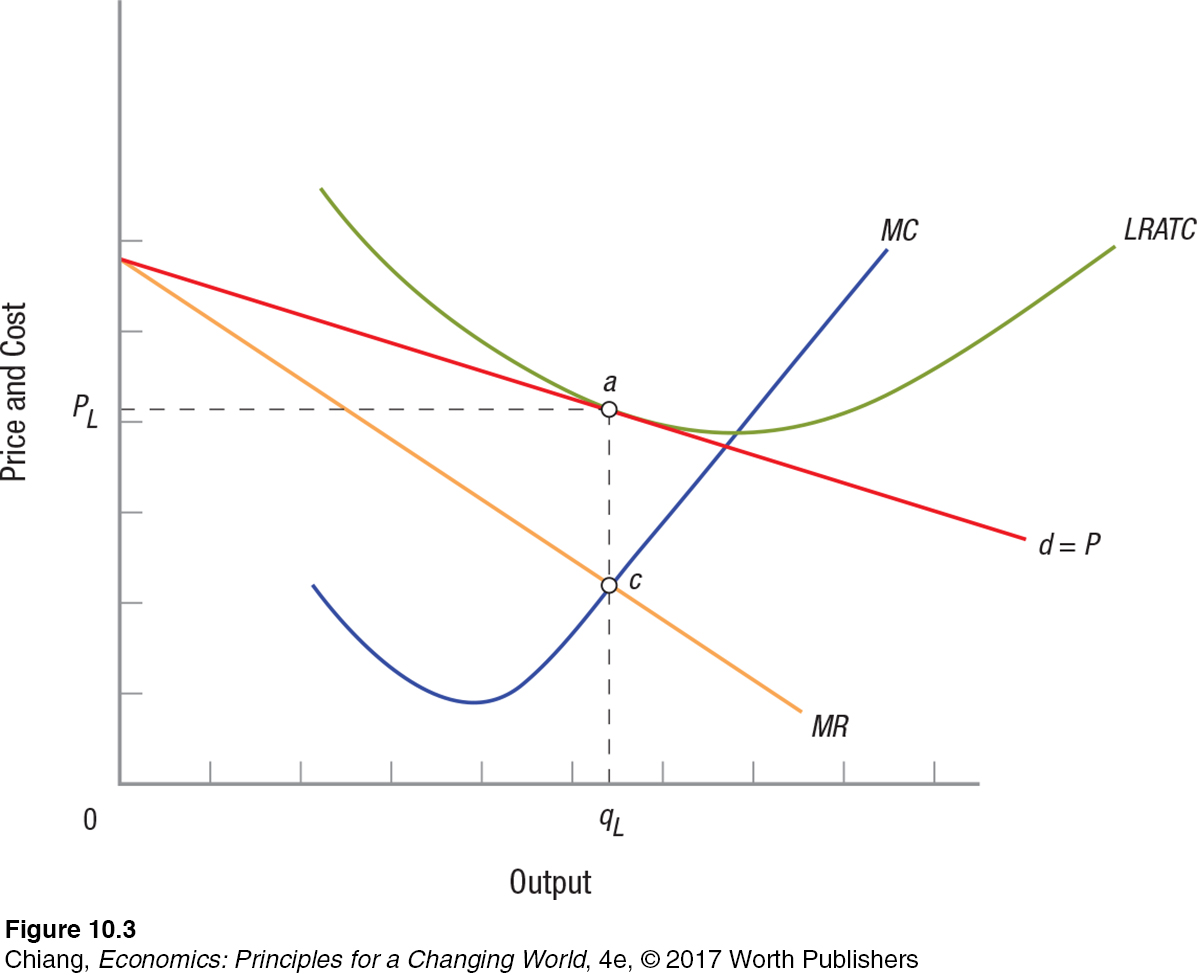

If firms in the industry are earning economic profits like those of the firm shown in Figure 2, new firms will want to enter. Since there are no restrictions to entry or exit, new firms will enter, soaking up some industry demand and reducing the demand to each firm in the market. Demand will continue to decline as long as economic profits exist. At equilibrium in the long run, the typical firm in the industry will look like the one shown in Figure 3.

Notice that the demand curve is just tangent to the long-

Comparing Monopolistic Competition to Perfect Competition

Are firms in monopolistically competitive industries as efficient as those in perfectly competitive industries? Because firms in both earn normal profits, one might think that both market structures are equally efficient. But they are not. Differentiated products create minimarkets within each industry. For example, Wrangler and True Religion are both brands of blue jeans, but each caters to a different set of customers, allowing True Religion to charge almost 10 times more per pair. And because differentiating products reduces economies of scale, the prices will be slightly higher.

The relatively small differences in price and output represent the cost we pay for greater variety and innovation. For example, dozens of flavors of sodas exist so that we need not drink the same brand every time. And watches offer everything from basic time and date to GPS capabilities and Internet service to cater to each customer’s intended use of the product. Product differentiation is important and for most of us valuable, but not free.

From this discussion, you might get some sense of the pressures firms face to differentiate their products. The more they can move away from the competitive model, the better chance they have of using their market power to make more profit. But because market power evaporates over the long run for monopolistically competitive firms, these firms have to try to sustain the value in the differentiated product. This is hard to do. The price premium charged by Hollister will not be paid when the Hollister brand is no longer as popular, or becomes more like everyone else. Yet, it is in the firm’s interest to product differentiate as long as it can. When you see firms trying to differentiate their products, ask yourself if the products are really so different after all.

A McDonald’s Big Mac Without Beef?

Why do U.S. fast-

There are few places left in the world that are not exposed to American fast-

Because beef is rarely eaten in India due to the sacred nature of cows in the Hindu religion, restaurants in India cater to local tastes and customs by using other meats such as chicken, lamb, or fish. When one visits a McDonald’s restaurant in Mumbai, the signature sandwich will resemble a Big Mac, but is called the Maharaja Mac, consisting of two chicken patties within three layers of buns. Of course, in major cities in India, you can still find real beef in select restaurants; these are the authentic foreign restaurants that cater to foreigners or Indian foodies seeking out a unique culinary experience. This is no different than American foodies seeking out authentic restaurants in the United States serving exotic dishes such as snake stew or chicken feet. It’s all about preferences.

Examples of fast-

Part of the success of multinational companies such as McDonald’s lies in knowing the preferences of their customers and the nature of their competition. Therefore, although product differentiation is necessary to gain market share, being too different, especially when a product goes against cultural norms, can hurt a company’s profits.

GO TO  TO PRACTICE THE ECONOMIC CONCEPTS IN THIS STORY

TO PRACTICE THE ECONOMIC CONCEPTS IN THIS STORY

CHECKPOINT

MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION

Monopolistically competitive firms look like perfectly competitive firms (a large number of firms in a market in which entry and exit are unrestricted), but have differentiated products.

Monopolistically competitive firms have elastic downward-

sloping demand curves. Similar to a monopolist, the short-

run equilibrium for a monopolistic competitor is the output level where MR = MC, and can result in positive, zero, or negative profits. In the long run, easy entry and exit result in monopolistically competitive firms earning only normal profits.

Monopolistically competitive firms have some market power. Therefore, output is lower and price is higher for monopolistically competitive firms when compared to price and output for perfectly competitive firms.

QUESTION: At Disney World in Florida, you can stay at the Disney Grand Floridian Resort for $350/night or at the Disney All-

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Although both hotels are located on Disney property, the Grand Floridian Resort is much closer to the theme parks, and is located on the Monorail for easy transportation throughout the park. Also, the Grand Floridian is an upscale hotel with many fine restaurants and shops, and offers luxurious room amenities. The All-