Measuring Inflation and Unemployment

17

Learning Objectives

17.1 Define inflation and explain how it is measured.

17.2 Use the consumer price index to estimate the effects of inflation on prices.

17.3 Describe the main causes of inflation.

17.4 Describe the economic consequences of the different forms of inflation.

17.5 Explain how “labor force,” “employment,” and “unemployment” are defined.

17.6 Compare alternative measures of unemployment that include marginally attached workers and underemployed workers.

17.7 Describe the different forms of unemployment and which ones can be influenced by government policies.

17.8 Explain what full employment means and how the natural rate of unemployment is measured.

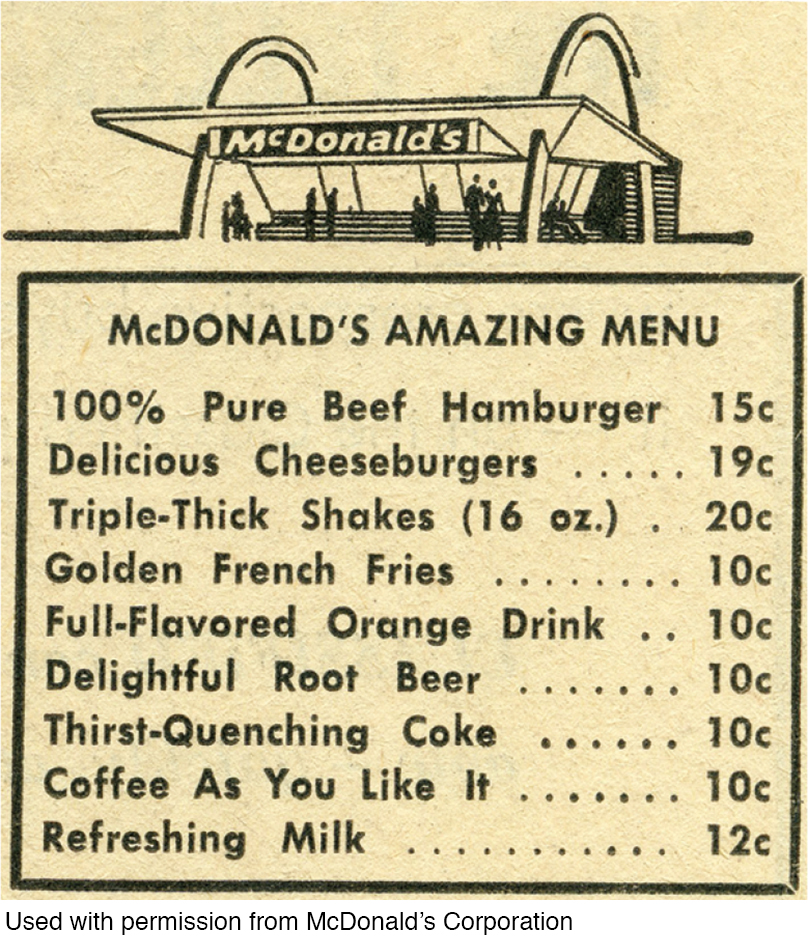

Fifty years ago, a single dollar bought a lot. A gallon of gasoline cost less than 30 cents, a movie theater ticket cost about 75 cents, and a meal at a relatively new restaurant chain called McDonald’s cost about 50 cents.

Today, none of these items can be purchased for a dollar. The general rise in prices in the economy is referred to as inflation. Inflation has fluctuated each year, ranging from less than 5% in the 1960s, to nearly 15% in 1980, to less than 2% in recent years. Inflation reduces the ability of consumers to purchase goods and services. Your dollar just does not go as far. Inflation is a macroeconomic issue because it reduces the purchasing power of both income and savings over time.

Another macroeconomic concern facing the economy is unemployment, which measures the number of workers without a job but who are actively seeking one. Like the inflation rate, the unemployment rate fluctuates from year to year, falling below 5% during the Internet boom of the late 1990s and the housing bubble in the early 2000s, and reaching 10% during the early 1980s and late 2000s. Unemployment is a concern because not only does it force unemployed people to cut back on consumption and to use up their savings, it influences the employed to cut back on their consumption as well. Unemployment puts considerable strain on the government when it results in lower tax revenues but higher spending on assistance programs for the unemployed.

Because inflation and unemployment can have such bad macroeconomic effects, they have been called the “twin evils” of the modern macroeconomy. Each alone is bad. Together, they amplify each other, making things worse.

In the 1960s, macroeconomists thought they had these twin evils beaten. Historical data led them to believe that inflation and unemployment were linked in an inverse fashion; when unemployment went up, inflation would go down, and vice versa. Macroeconomists thought policymakers faced a menu of choices. Pick an unemployment rate from column A and get a corresponding inflation rate from column B. Better yet, the rates at issue were thought to be relatively low: An inflation rate of 3% to 4% was thought to be needed to keep unemployment under 4%. For those unemployed in the 2007–

Unfortunately, the data amassed in the 1960s gave a false reading, as the high unemployment and high inflation rates of the 1970s proved. According to the 1960s macroeconomic model, the macroeconomy was just not supposed to witness the twin evils together.

Jump ahead to 2016. After a long recovery since 2009 that saw persistent unemployment for several years, the silver lining was that inflation was low throughout the recovery, again confirming the trend that unemployment and inflation tend to run opposite of each other. But as the official unemployment rate fell below 5% in 2016, inflation did not rise, largely due to a steep drop in energy prices. Because both unemployment and inflation were low, the twin evils appeared seemingly defeated . . . but were they? Economists have pointed out that the extraordinary measures taken during and after the last recession resulted in growing debt and a large infusion of money into the economy, policies that could eventually lead to higher inflation. And if the slowdown in the global economy increases unemployment in the near future, we might have to confront the twin evils together again.

By now, you might be wondering: What is the big deal about inflation? You have a visceral sense that unemployment is bad. Inflation is less tangible. Thus, this chapter will start with inflation, what it is, how it is measured, and why it is bad. Then we will turn to unemployment. How does the government define the unemployment rate? An Uber driver with a Ph.D. is employed, but is he or she really underemployed? Is someone who has given up looking for a job considered unemployed? You may be surprised at the answers.

The chapter then will categorize the types of unemployment, revealing which type can be moderated by government policies and which cannot. Finally, we will return to a key concern from the last chapter: the slow economic recovery that reduced the overall number of people seeking jobs.