chapter summary

chapter summary

Section 1 Aggregate Demand

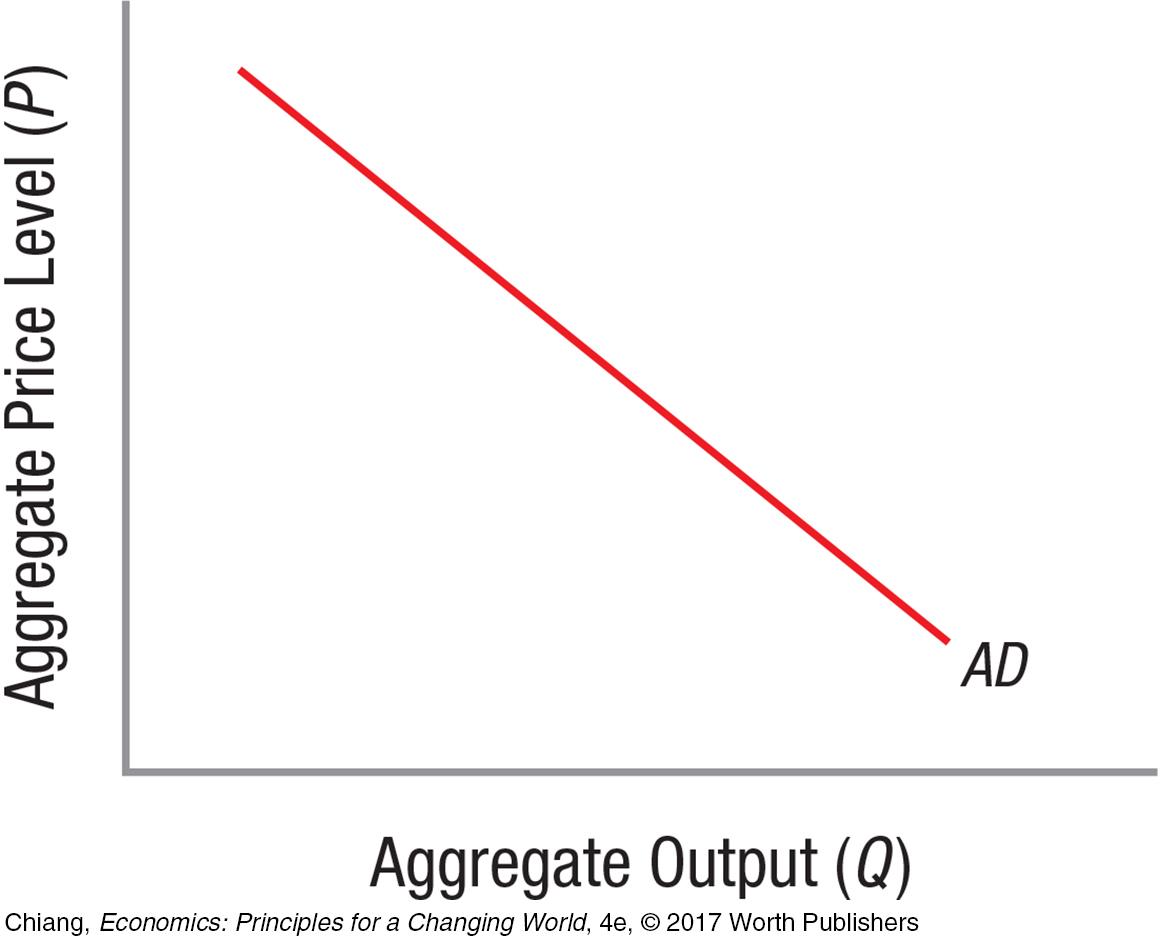

20.1 The aggregate demand curve shows the quantity of goods and services (real GDP) demanded at different price levels.

20.2 The aggregate demand curve is downward-

Wealth effect: When price levels rise, the purchasing power of money saved falls.

Export price effect: Rising price levels cause domestic goods to be more expensive in the global marketplace, resulting in fewer purchases by foreign consumers.

Interest rate effect: When price levels rise, people need more money to carry out transactions. The added demand for money drives up interest rates, causing investment spending to fall.

20.3 The determinants of aggregate demand include the components of aggregate spending:

Consumption spending

Investment spending

Government spending

Net exports

Changing any one of these aggregates will shift the aggregate demand curve.

Section 2 Aggregate Supply

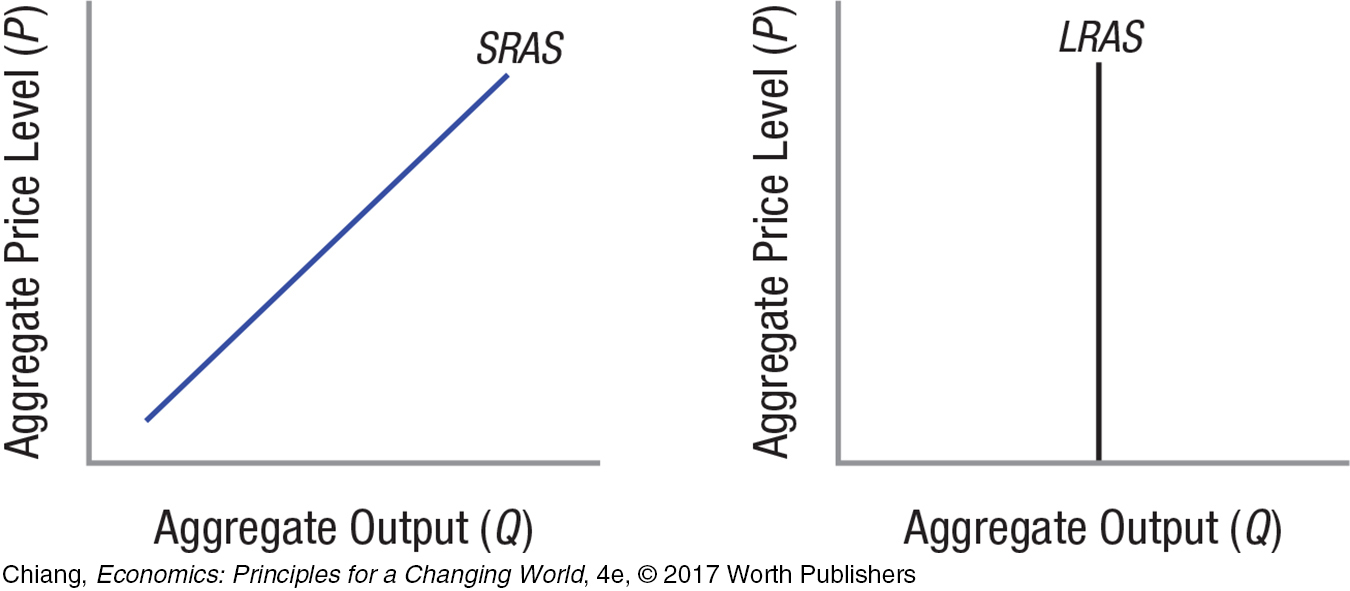

20.4 The aggregate supply curve shows the real GDP firms will produce at varying price levels.

In the short run, aggregate supply is upward-

In the long run, aggregate supply is vertical (LRAS).

In the short run, prices and wages are sticky (think of menu prices staying the same for a period of time). Therefore, firms respond by increasing output when prices rise.

In the long run, prices and wages adjust; therefore, output is not affected by the price level.

20.5 Factors that shift the SRAS curve:

Input prices

Productivity

Taxes and regulation

Market power of firms

Inflationary expectations

Electronic toll collection booths save time and reduce transportation costs to firms, leading to an increase in short-

Factors that shift the LRAS curve:

Increase in technology

Greater human capital

Trade

Innovation and R&D

Section 3 Macroeconomic Equilibrium

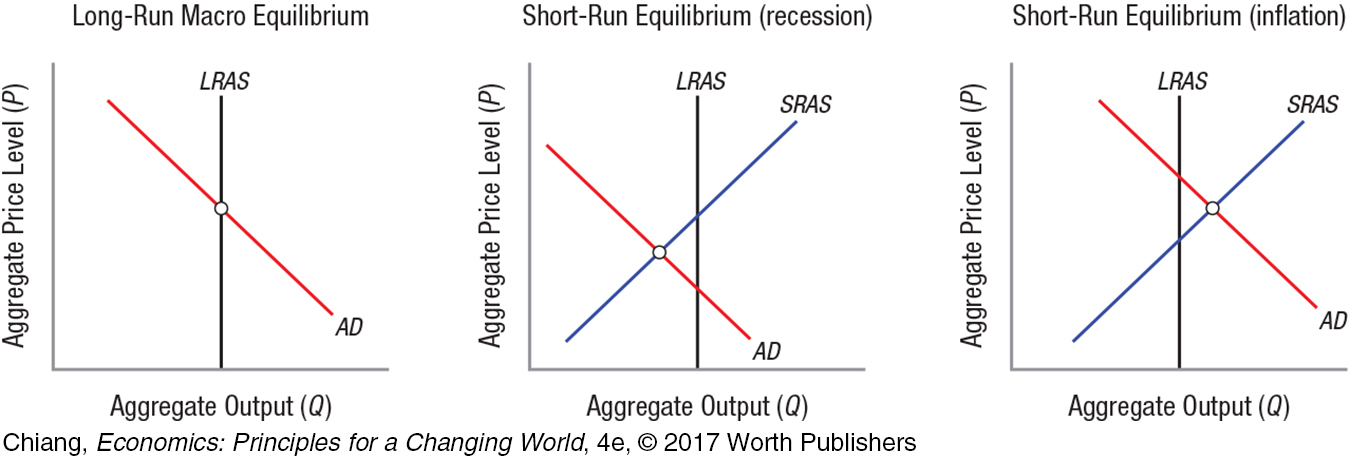

20.6 A long-

A short-

20.7 The spending multiplier exists because new spending generates income that results in more spending and income, based on the marginal propensities to consume and save.

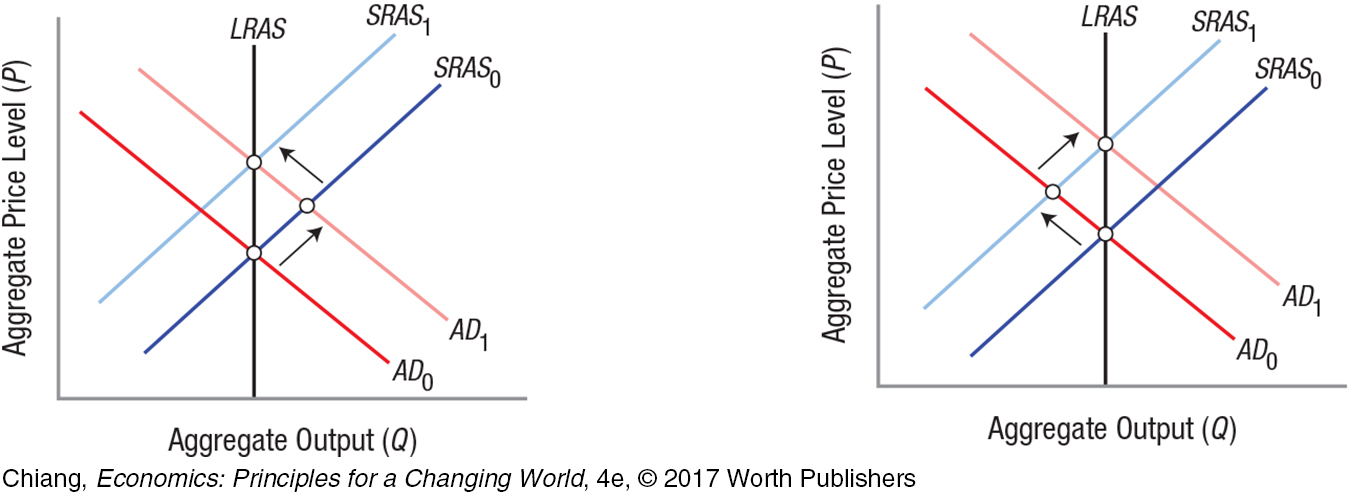

20.8 Demand-

Multiplier Example: MPC = 0.80 and MPS = 0.20

Round 1: $100 in new spending = $100 in new income.

Round 2: $80 is spent and $20 is saved ($80 in new income).

Round 3: $64 is spent and $16 is saved.

Round 4: $51.20 is spent and $12.80 is saved.

Round 5: $40.96 is spent and $10.24 is saved.

Round 6: $32.76 is spent and $8.20 is saved.

...

Round n: $0.01 is spent and $0.00 is saved.

Total Effect of $100 in Spending = $500 in Spending and $100 in Savings

Multiplier = 1/(1 − MPC) = 1/(1 − 0.80) = 5

Cost-