FISCAL POLICY AND AGGREGATE DEMAND

When an economy faces underutilization of resources because it is stuck in equilibrium well below full employment, we saw that increases in aggregate demand can move the economy toward full employment without generating excessive inflation pressures. However, in normal times, influencing aggregate demand brings with it a tradeoff: Output is increased at the expense of raising the price level.

In contrast, consider decreasing aggregate demand. When the economy is in an inflationary equilibrium above full employment, contracting aggregate demand dampens inflation but leads to another tradeoff: unemployment. Before we examine the theory behind how government actually goes about influencing aggregate demand by using fiscal policy, let’s take a brief look at what categories of spending fiscal policy typically alters.

Discretionary and Mandatory Spending

discretionary spending The part of the budget that works its way through the appropriations process of Congress each year and includes national defense, transportation, science, environment, and income security.

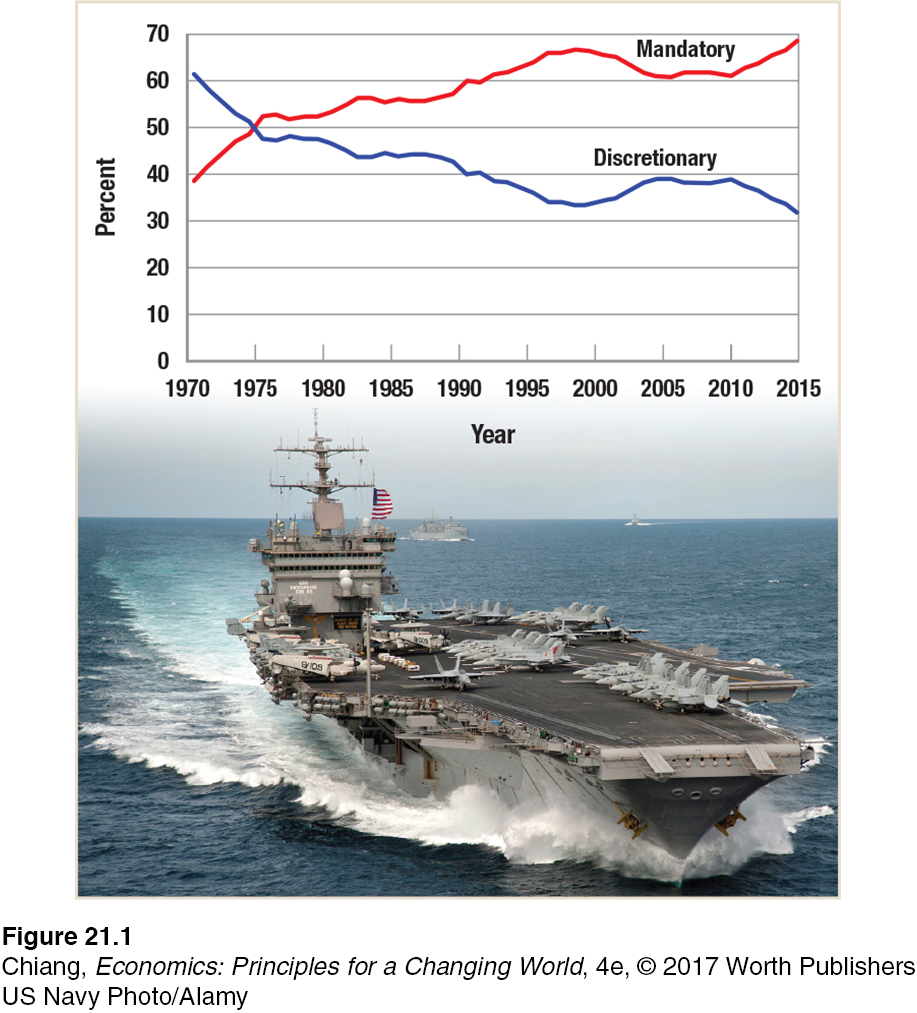

The federal budget can be split into two distinct types of spending: discretionary and mandatory. Discretionary spending is the part of the budget that works its way through the appropriations process of Congress each year. Discretionary spending includes such programs as national defense (primarily the military), transportation, science, environment, income security (some welfare programs and a large portion of Medicaid), education, and veterans benefits and services. As Figure 1 shows, discretionary spending has steadily declined as a percent of the budget since the 1960s, when it was over 60% of the budget, to about one-

mandatory spending Spending authorized by permanent laws that does not go through the same appropriations process as discretionary spending. Mandatory spending includes Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the national debt.

Mandatory spending is authorized by permanent laws and does not go through the same appropriations process as discretionary spending. To change one of the entitlements of mandatory spending, Congress must change the law. Mandatory spending includes such programs as Social Security, Medicare, part of Medicaid, interest on the national debt, and some means-

Even though discretionary spending is only 32% of the budget, this is still roughly $1.2 trillion, and the capacity to alter this spending is a powerful force in the economy. Therefore, we are mainly concerned with discretionary spending when we consider fiscal policy.

Discretionary Fiscal Policy

discretionary fiscal policy Policies that involve adjusting government spending and tax policies with the express short-

The exercise of discretionary fiscal policy is done with the express goal of influencing aggregate demand. It involves adjusting government spending and tax policies to move the economy toward full employment, encouraging economic growth, or controlling inflation.

Some examples of the use of discretionary fiscal policy include tax cuts enacted during the Kennedy, Reagan, and George W. Bush administrations. These tax cuts were designed to expand the economy under the belief that people would spend their tax savings, both in the near term and the long run—

Government Spending Although discretionary fiscal policy can get complex, the impact of changes in government spending is relatively simple. As we know, a change in government spending or other components of GDP will cause income and output to rise or fall by the spending change times the multiplier.

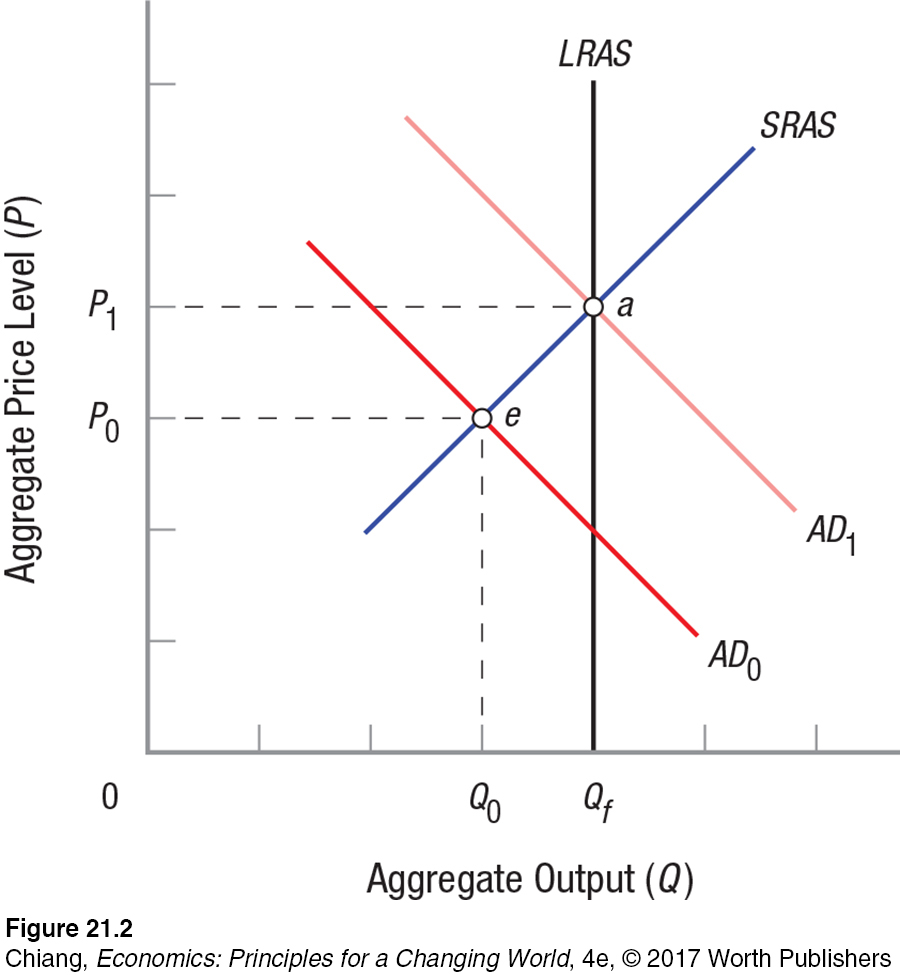

This is illustrated in Figure 2 with the economy initially in equilibrium at point e, with real output at Q0. If government spending increases, shifting aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1, aggregate output will increase from Q0 to Qf. Because the short-

Once the economy reaches full employment (point a), further spending is not multiplied as the economy moves along the LRAS curve, and only higher prices result. Finally, keep in mind that the multiplier works in both directions.

Taxes Changes in government spending modify income by an amount equal to the change in spending times the multiplier. How, then, do changes in taxes affect the economy? The answer is not quite as simple. Let’s begin with a reminder of what constitutes spending equilibrium.

When the economy is in equilibrium,

GDP = C + I + G + (X − M)

At equilibrium, all spending injections into the economy equal all withdrawals of spending. To review, injections are activities that increase spending in an economy, such as investment (I), government spending (G), and exports (X). Withdrawals, on the other hand, are activities that remove spending from the economy, such as saving (S), taxes (T), and imports (M). Therefore, in equilibrium:

I + G + X = S + T + M

With this equation in hand, let’s focus on taxes. When taxes are increased, money is withdrawn from the economy’s spending stream. When taxes are reduced, consumers and businesses have more to spend. Disposable income is equal to income minus taxes (Y − T ).

Because taxes represent a withdrawal of spending from the economy, we would expect equilibrium income to fall when a tax is imposed. Consumers pay a tax increase, in part, by reducing their saving. If we initially increase taxes by $100, let’s assume that consumers draw on their savings for $25 of the increase in taxes. Because this $25 in savings was already withdrawn from the economy, only the $75 in reduced spending gets multiplied, reducing the change in income. The reduction in saving of $25 dampens the effect of the tax on equilibrium income because those funds were previously withdrawn from the spending stream. Changing the withdrawal category from saving to taxes does not affect income. A tax decrease has a similar but opposite impact because only the MPC part is spent and multiplied, and the rest is saved and thus withdrawn from the spending stream.

The result is that a tax increase (or decrease, for that matter) has less of a direct impact on income, employment, and output than an equivalent change in government spending. Another way of saying this is that the government tax multiplier is less than the government spending multiplier. Therefore, added government spending leads to a larger increase in GDP when compared to the same reduction in taxes.

Transfers Transfer payments are money payments paid directly to individuals. These include payments for such items as Social Security, unemployment compensation, and welfare. In large measure, they represent our social safety net. We will ignore them as part of the discretionary fiscal policy, because most are paid as a matter of law, but we will see later in the chapter that they are very important as a way of stabilizing the economy.

Expansionary and Contractionary Fiscal Policy

expansionary fiscal policy Policies that increase aggregate demand to expand output in an economy. These include increasing government spending, increasing transfer payments, and/or decreasing taxes.

Expansionary fiscal policy involves increasing government spending (such as on highways and education), increasing transfer payments (such as unemployment benefits), and/or decreasing taxes—

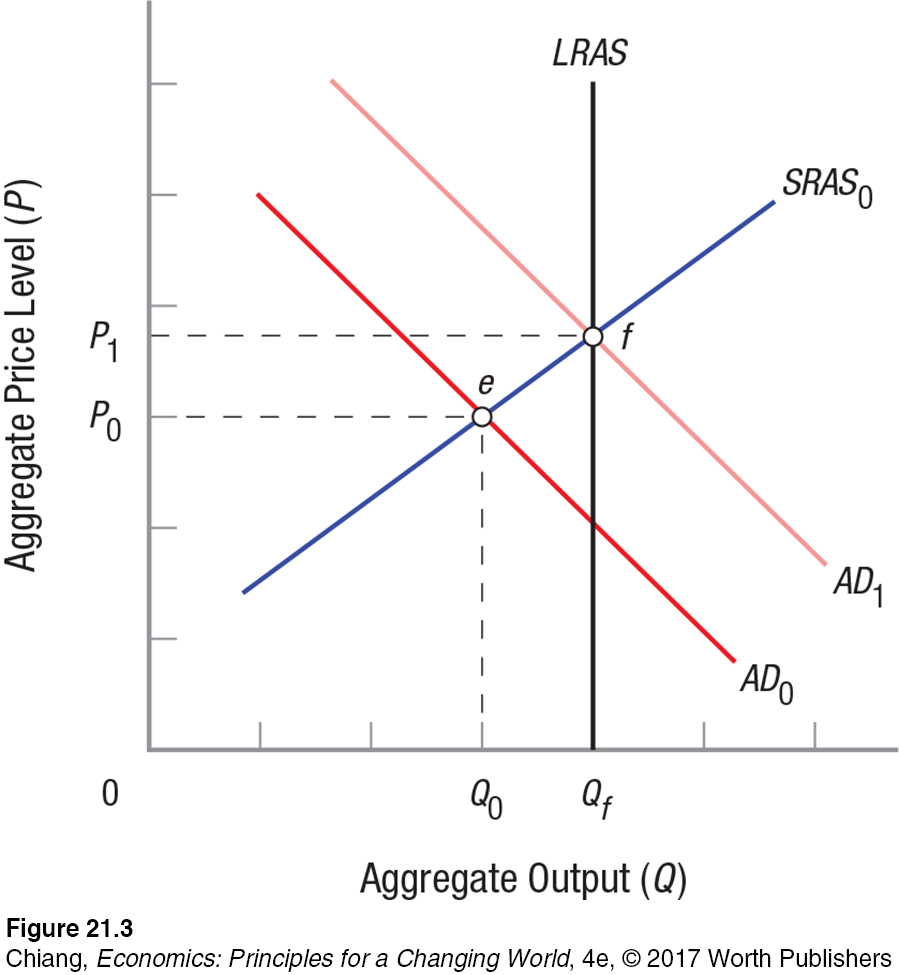

When the economy is below full employment, an expansionary policy will move the economy to full employment, as Figure 3 shows. The economy begins at equilibrium at point e, below full employment. Expansionary fiscal policy increases aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1, and equilibrium output rises to Qf (point f) as the price level rises to P1. In this case, one good outcome results—

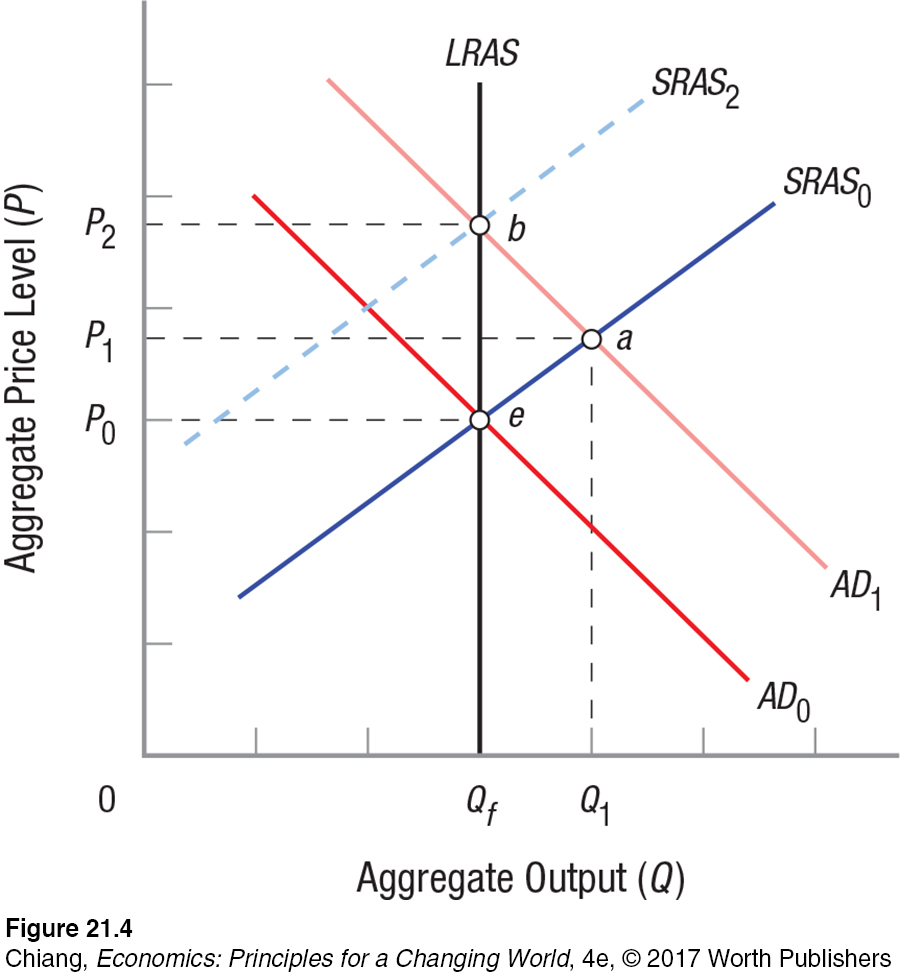

Figure 4 shows what happens when the economy is at full employment. An expansionary policy raises prices without producing any long-

contractionary fiscal policy Policies that decrease aggregate demand to contract output in an economy. These include reducing government spending, reducing transfer payments, and/or raising taxes.

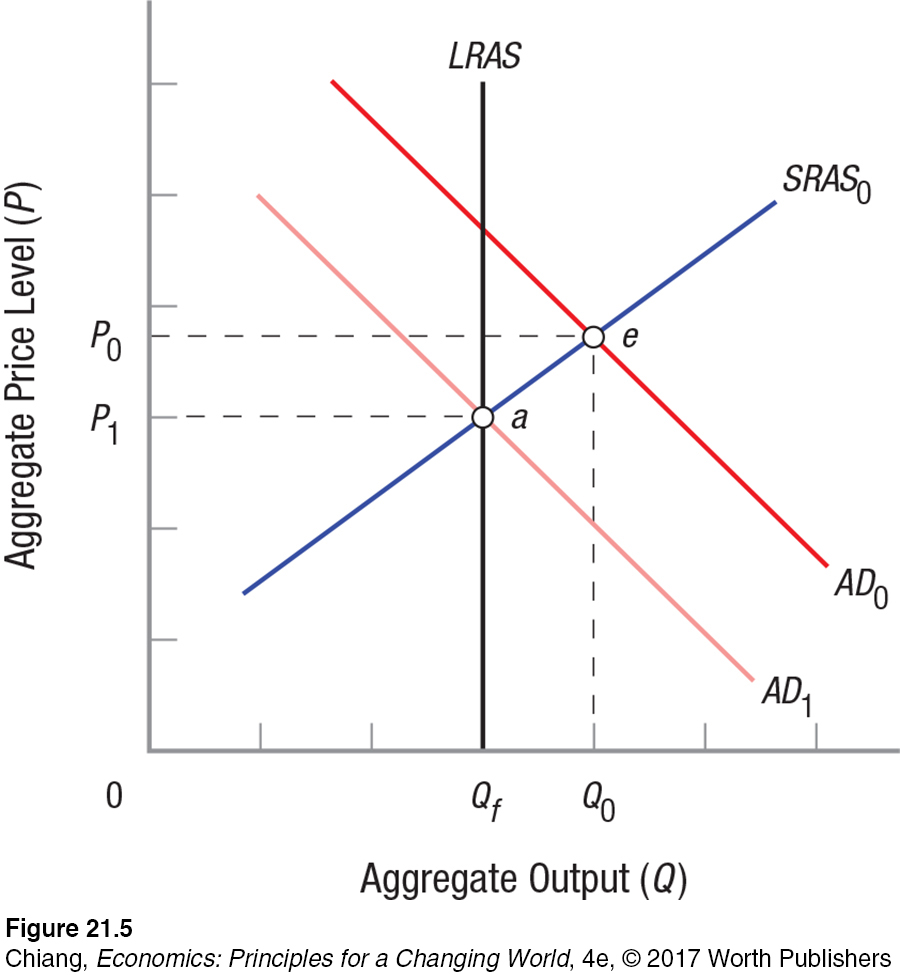

When an economy moves to a point beyond full employment, as just described, economists say an inflationary spiral has set in. The explanation for this phenomenon was suggested earlier. Still, we can already see that one way to reduce such inflationary pressures is to use contractionary fiscal policy. These policies include reducing government spending, reducing transfer payments, and/or raising taxes (increasing withdrawals from the economy). Figure 5 shows the result of contractionary policy. The economy is initially overheating at point e, with output above full employment. Contractionary policy reduces aggregate demand to AD1, bringing the economy back to full employment at price level P1 and output Qf .

Exercising demand-

CHECKPOINT

FISCAL POLICY AND AGGREGATE DEMAND

Demand-

side fiscal policy involves using government spending, transfer payments, and taxes to influence aggregate demand and equilibrium income, output, and the price level in the economy. In the short run, government spending raises income and output by the amount of spending times the multiplier. Tax reductions have a smaller impact on the economy than government spending because some of the reduction in taxes is added to saving and is therefore withdrawn from the economy.

Expansionary fiscal policy involves increasing government spending, increasing transfer payments, and/or decreasing taxes.

Contractionary fiscal policy involves decreasing government spending, decreasing transfer payments, and/or increasing taxes.

When an economy is at full employment, expansionary fiscal policy may lead to greater output in the short term, but will ultimately just lead to higher prices in the longer term.

Politicians tend to favor expansionary fiscal policy because it can bring with it increases in employment although with increasing inflation. Politicians tend to shun contractionary fiscal policy because it brings unemployment.

QUESTION: During the 2007–

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Although the money would have hit the economy sooner, a significant portion of the proceeds would have been saved or used to pay existing bills, potentially limiting the stimulative impact of added spending. The other benefit of the infrastructure package is that by being spread out over several years, it won’t just be a big jolt to the economy that ends as fast as it began. Thus, the impact on employment and business planning was smoother.