FINANCING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

In the late 1990s, an economic boom fueled by the expansion of the Internet and “dot com” industries resulted in tremendous economic growth and low unemployment. In 1998 an increase in tax revenues collected as a result of higher incomes and on profits earned from a rising stock market led to tax revenues exceeding government spending for the first time in nearly 30 years. This trend lasted four years until 2002, when the government again spent more than it collected in taxes, and has since never reversed course. This section begins by defining deficits and surpluses, national debt, and public debt before studying their impact on the economy.

Defining Deficits and the National Debt

deficit The amount by which annual government expenditures exceed tax revenues.

surplus The amount by which annual tax revenues exceed government expenditures.

national debt The total debt issued by the U.S. Treasury, which represents the total accumulation of past deficits less surpluses. A portion of this debt is held by other government agencies, and the rest is held by the public. It is also referred to as the gross federal debt.

public debt The portion of the national debt that is held by the public, including individuals, companies, pension funds, along with foreign entities and foreign governments. This debt is also referred to as net debt or federal debt held by the public.

A deficit is the amount by which annual government expenditures exceed tax revenues. A surplus is the amount by which annual tax revenues exceed government expenditures. In 2000 the budget surplus was $236.2 billion. By 2002 tax cuts, a recession, and new commitments for national defense and homeland security had turned the budget surpluses of 1998–

The gross federal debt, or more commonly known as the national debt, is the total accumulation of past deficits less surpluses. The national debt is measured as the total amount of debt issued by the U.S. Treasury (including Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, and Savings bonds). The national debt in 2016 was over $19 trillion. However, a portion of this debt is held by other agencies of government, such as the Social Security Administration, the Treasury Department, and the Federal Reserve, in what is referred to as an intergovernmental transfer. What exactly does this mean?

Suppose you have a savings account with funds to be used to pay your college tuition, but due to an unexpected expensive $2,000 car repair, you temporarily borrowed from your college savings account by withdrawing $800 and borrowed the remaining $1,200 using a credit card. Although you fully intend to pay back the full $2,000 in debt (including your college savings), only $1,200 is owed to someone other than yourself. Similarly, part of the total debt that the government has incurred is owed to itself, and the rest is owed to the public.

The public debt, also known as the net debt or federal debt held by the public, is the portion of the national debt that is held by individuals, companies, and pension funds, along with foreign entities and foreign governments. Public debt represents a real claim on government assets, and is the debt that is more scrutinized when analyzing the health of the macroeconomy.

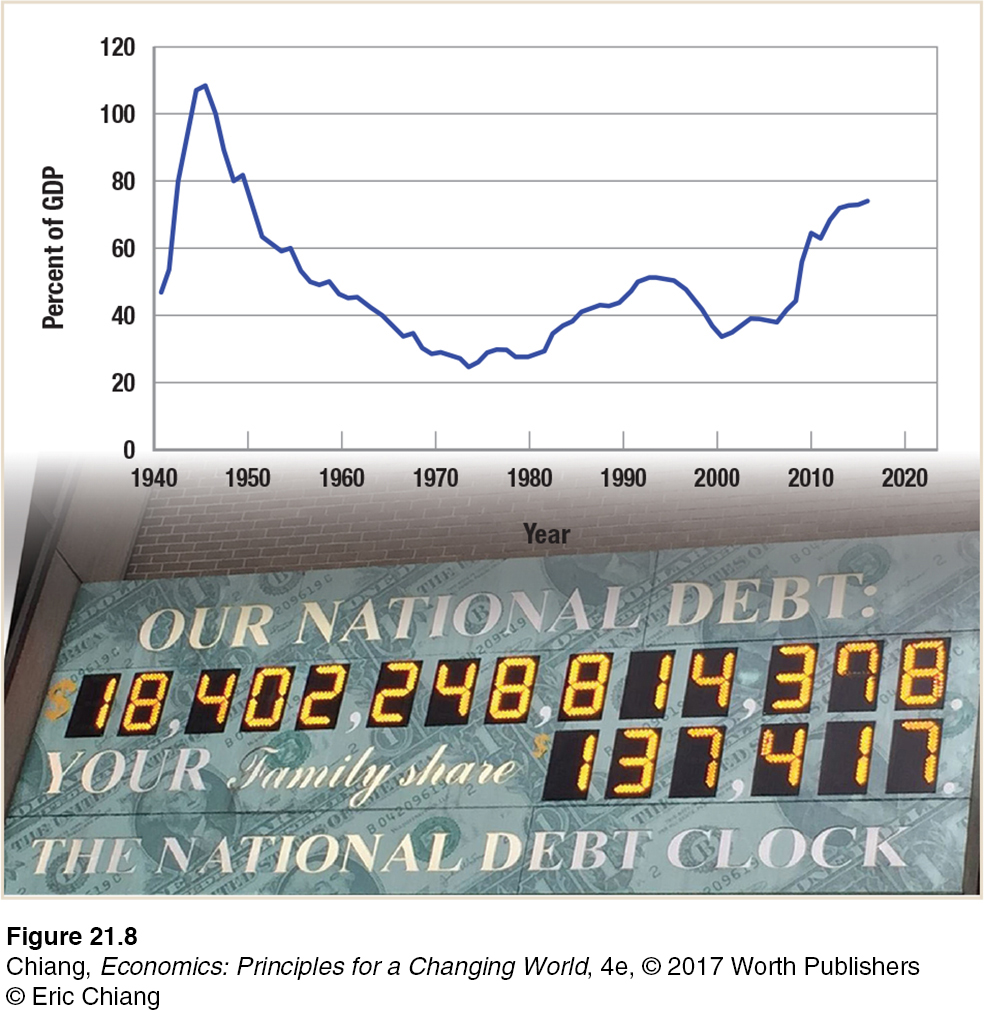

In sum, the national debt and public debt are distinct measures of the extent to which government spending has exceeded tax revenues over the course of time. Figure 8 shows the public debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) since 1940. During World War II, public debt exceeded GDP. It then trended downward until the early 1980s, when public debt began to climb again. Public debt as a percentage of GDP fell from the mid-

Public debt is held as U.S. Treasury securities, including Treasury bills, notes, bonds, and U.S. Savings Bonds. Treasury bills, or T-

Treasury notes are financial instruments issued for periods ranging from 1 to 10 years, whereas Treasury bonds have maturity periods exceeding 10 years. Both of these instruments have stated interest rates and are traded sometimes at discounts and sometimes at premiums.

Today, interest rates on the public debt are between 1% and 4%. This relatively low rate has not always been the case. In the early 1980s, interest rates varied from 11% to nearly 15%. Inflation was high and investors required high interest rates as compensation. When rates are high, government interest costs on the debt soar.

Balanced Budget Amendments

Although federal budget deficits have been the norm for the past 50 years, the 2007–

annually balanced budget Expenditures and taxes would have to be equal each year.

cyclically balanced budget Balancing the budget over the course of the business cycle by restricting spending or raising taxes when the economy is booming and using these surpluses to offset the deficits that occur during recessions.

Most balanced budget amendments require an annually balanced budget, which means government would have to equate its revenues and expenditures every year. Most economists, however, believe such rules are counterproductive. For example, during times of recession, tax revenues tend to fall due to lower incomes and higher unemployment. To offset these lost revenues, an annually balanced budget would require deep spending cuts or tax hikes (in other words, contractionary fiscal policy) during a time when expansionary fiscal policies are needed. Many economists believe that balanced budget rules of the early 1930s turned what probably would have been a modest recession into the global Depression.

An alternative to balancing the budget annually would be to require a cyclically balanced budget, in which the budget is balanced over the course of the business cycle. The basic idea is to restrict spending or raise taxes when the economy is booming, allowing for a budget surplus. These surpluses would then be used to offset deficits accrued during recessions, when increased spending or lower taxes are appropriate. To some extent, balancing the budget over the business cycle happens automatically as long as fiscal policy is held constant due to the automatic stabilizers discussed earlier. However, the business cycle takes time to define (due to lags), making it difficult to enforce such a rule in practice.

ISSUE

How Big Is the Economic Burden of Interest Rates on the National Debt?

The federal government paid $223 billion in interest payments on the national debt in 2016. This is money that could have been used for other public programs. In fact, interest payments on the debt were greater than the amount the government paid for education, transportation infrastructure, low-

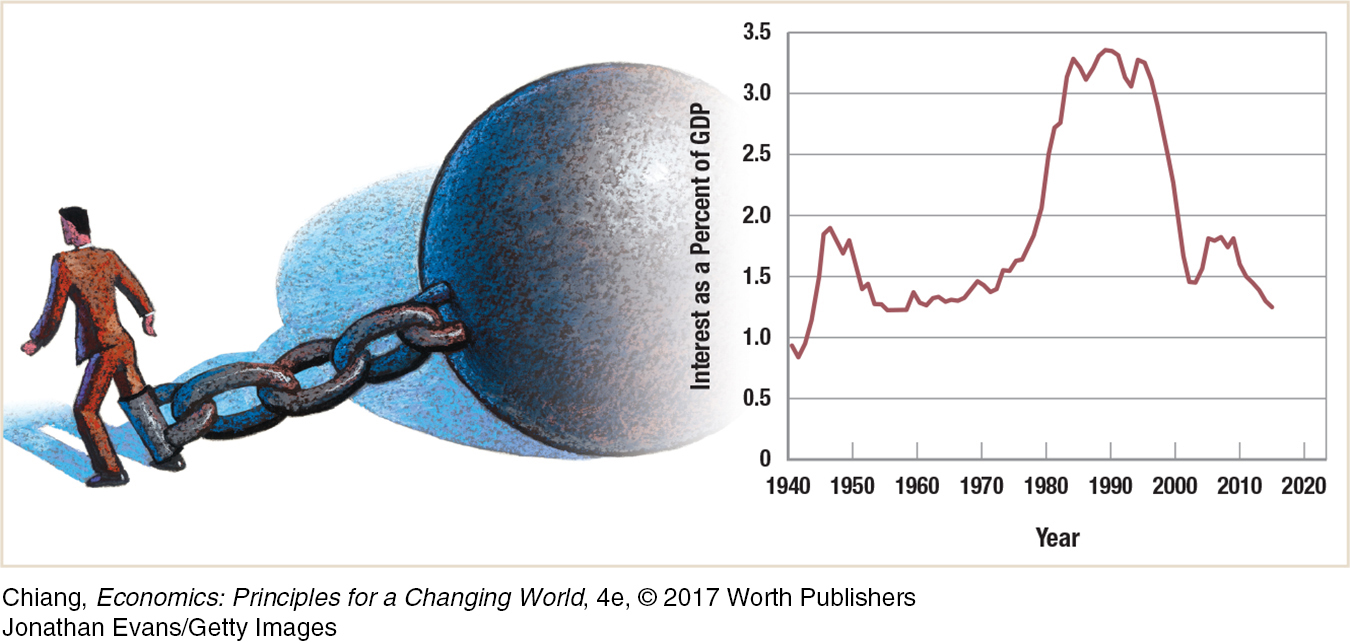

Although interest payments on the debt are large, they represent a small portion of the federal budget and an even smaller portion of GDP. Interest on the debt as a percentage of GDP, as shown in the figure, was steady from 1950 to 1980, hovering around 1.5%. This percentage more than doubled during the 1980s because of high inflation and interest rates, and rising deficits. In the 1990s, interest rates dropped and deficits fell, allowing interest payments as a percentage of GDP to fall toward the level it was in the 1950s. The rising debt associated with the 2007–

The fact that rising debt has not led to dramatic borrowing costs highlights the important role that interest rates have on the economy. Many individuals, firms, and foreign governments hold long-

Today, those 15% bonds from the 1980s have matured, and new 30-

Why have long-

Despite the current favorable conditions under which the U.S. government finances its debt, it must still focus on keeping debt in check for a number of reasons. For example, interest payments on external (foreign) holdings of U.S. debt are a leakage from our economy. Also, as interest rates rise in the future, low interest rate bonds issued today will mature and be replaced by higher interest rate bonds.

functional finance An approach that focuses on fostering economic growth and stable prices, while keeping the economy as close as possible to full employment.

Finally, some economists believe that balancing the budget should not be the primary concern of policymakers; instead, they view the government’s primary macroeconomic responsibility to foster economic growth and stable prices, while keeping the economy as close as possible to full employment. This is the functional finance approach to the budget, where governments provide public goods and services that citizens want (such as national defense and education) and focus on policies that keep the economy growing, because rapidly growing economies do not have significant public debt or deficit issues.

In sum, balancing the budget annually or over the business cycle may be either counterproductive or difficult to do. It is not a solution to the public choice problem previously discussed of politicians’ incentives to spend and not raise taxes. Budget deficits begin to look like a normal occurrence in our political system.

Financing Debt and Deficits

Seeing as how deficits may be persistent, how does the government deal with its debt, and what does this imply for the economy? Government deals with debt in two ways. It can either borrow or sell assets.

government budget constraint The government budget is limited by the fact that G − T = ΔM + ΔB + Δ A.

Given its power to print money and collect taxes, the federal government cannot go bankrupt per se. But it does face what economists call a government budget constraint:

G − T = ΔM + ΔB + ΔA

where

G = government spending

T = tax revenues; thus, (G − T) is the federal budget deficit

ΔM = the change in the money supply (selling bonds to the Federal Reserve)

ΔB = the change in bonds held by public entities, domestic and foreign

ΔA = the sales of government assets

The left side of the equation, G − T, represents government spending minus tax revenues. A positive (G − T) value is a budget deficit, and a negative (G − T) value represents a budget surplus. The right side of the equation shows how government finances its deficit. It can sell bonds to the Federal Reserve, sell bonds to the public, or sell assets. Let’s look at each of these options.

ΔM > 0: First, the government can sell bonds to government agencies, especially the Federal Reserve, which we will study in depth in a later chapter. When the Federal Reserve buys bonds, it uses money that is created out of thin air by its power to “print” money. When the Federal Reserve pumps new money into the money supply to finance the government’s debt, it is called monetizing the debt.

ΔB > 0: If the Federal Reserve does not purchase the bonds, they may be sold to the public, including corporations, banks, mutual funds, individuals, and foreign entities. This also has the effect of financing the government’s deficit.

ΔA > 0: Asset sales represent only a small fraction of government finance in the United States. These sales include auctions of telecommunications spectra and offshore oil leases. Developing nations have used asset sales, or privatization, in recent years to bolster sagging government revenues and to encourage efficiency and development in the case where a government-

owned industry is sold.

Thus, when the government runs a deficit, it must borrow funds from somewhere, assuming it does not sell assets. If the government borrows from the public, the quantity of publicly held bonds will rise; if it borrows from the Federal Reserve, the quantity of money in circulation will rise.

The main idea from this section is that deficits must be financed in some form, whether by the government borrowing or selling assets. As we’ll see in the next section, rising levels of deficits and the corresponding interest rates raise some important issues about the ability of a country to manage its debt burden.

CHECKPOINT

FINANCING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

A deficit is the amount that government spending exceeds tax revenue in a particular year.

The public (national) debt is the total accumulation of past deficits less surpluses.

Approaches to financing the federal government include annually balancing the budget, balancing the budget over the business cycle, and ignoring the budget deficit and focusing on promoting full employment and stable prices.

The federal government’s debt must be financed by selling bonds to the Federal Reserve (“printing money” or “monetizing the debt”), by selling bonds to the public, or by selling government assets. This is known as the government budget constraint.

QUESTION: One reason why state governments have been more willing to pass balanced budget amendments than the federal government is the difference between mandatory and discretionary spending. What are some expenses of the federal government that are less predictable or harder to cut that make balanced budget amendments more difficult to pursue?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

The federal government must satisfy its mandatory spending requirements, including Social Security, unless it passes a law to reform such spending. Also, the federal government must pay for national defense, including wars, which are unpredictable. Also unpredictable are expenses related to natural disasters, which require action by various federal agencies. Because of the combination of various mandatory spending programs and unpredictable discretionary spending requirements, the federal government would find it difficult in practice to enforce a balanced budget amendment.