FINANCIAL TOOLS FOR A BETTER FUTURE

Now that we have discussed the role of money, the market for loanable funds, and financial intermediaries, we should step back and ask ourselves how we can apply what we have learned to our everyday finances and our future. As a caveat, it is always best to seek financial advice from a trusted professional who has your best interests in mind. This section is meant to introduce you to the basic financial concepts encountered when borrowing and saving money.

Short-Term Borrowing

As a college student, your income is low to nonexistent as you invest (very wisely) in human capital by pursuing a college degree that will increase your earning potential during your working years. That means that in the near term, you will likely accumulate debt in the form of student loans, credit card balances, and car loans. Eventually, a home mortgage might also necessitate more borrowing.

Interest rates on personal debt vary considerably, with small differences leading to substantial payments over the long run, as we will see shortly. Student loans funded by the government typically offer low interest rates in addition to allowing you to defer payments until after you graduate. These loans often provide the lowest cost of borrowing to get you through until your income rises.

teaser rates Promotional low interest rates offered by lenders for a short period of time to attract new customers and to encourage spending.

The most common short-

Because of the high costs of holding credit card debt, it is generally advisable to:

Keep credit card balances to a minimum.

Find lower cost borrowing opportunities (such as student loans or bank loans) to keep higher interest credit card balances lower.

Avoid applying for too many credit cards, because fees can rack up and credit scores can be negatively affected by excessive credit applications.

Never miss a minimum payment, for any amount, even for a month. Every missed payment remains on credit reports for years, potentially raising costs for future car loans and home mortgages, and even making insurance and certain jobs harder to find.

The Power (or Danger) of Compounding Interest

Interest rates are an important factor in deciding how to go about borrowing, or saving, money. For the most part, we see interest rates as being quite low, typically less than 10%. The exceptions typically are for credit card debt or high-

compounding effect The effect of interest added to existing debt or savings leading to substantial growth in debt or savings over the long run.

But even for low interest rates, the effect on long-

| TABLE 1 | COMPOUNDING INTEREST AND DEBT | |||||

| Year | Starting Value | 10% Interest | Ending Value | |||

| 1 | $1,000.00 | $100.00 | $1,100.00 | |||

| 2 | 1,100.00 | 110.00 | 1,210.00 | |||

| 3 | 1,210.00 | 121.00 | 1,331.00 | |||

| 4 | 1,331.00 | 133.10 | 1,464.10 | |||

| 5 | 1,464.10 | 146.41 | 1,610.51 | |||

| ... | ... | ... | ... | |||

| 28 | 13,109.99 | 1,311.00 | 14,420.99 | |||

| 29 | 14,420.99 | 1,442.10 | 15,863.09 | |||

| 30 | 15,863.09 | 1,586.31 | 17,449.40 | |||

This may not seem like much. But suppose you do not make any payments on the debt for 30 years. Your original $1,000 debt will become $17,449! In fact, in year 30 alone, nearly $1,600 in interest would be added to the debt, more than the original borrowed amount. That is the danger of compounding interest on borrowed debt, and an important reason to seek low interest rates and make adequate payments. The good news, however, is that while compounding works against those with debt, it helps those who save, leading to higher future wealth.

Risk Assessment and Asset Allocation

As you work and accumulate savings, an important question is how to go about putting unspent money into assets that will grow over the years until you eventually need it.

The simplest and most liquid means of saving might be to keep money in cash stashed in a safe place or just letting money sit in a checking or savings account at your local bank. Although these methods give you the quickest access to your money, they are unlikely to provide much gain in value. Most checking accounts and even savings accounts pay no interest (and if they do, it’s often less than 1%). With inflation, when you eventually want to use the money, the purchasing power of that money has decreased. How does one go about choosing an asset that pays higher returns?

An important consideration when choosing the type of investment is assessing your tolerance for risk. Would you be frantic if you see your savings fluctuate up and down each day? Would you instead prefer to see steady growth of your savings? Or would you be willing to accept some volatility, the fact that some investments may fall in value, in exchange for a chance of higher growth over the long term?

Risk tolerance should reflect the type of investment instruments purchased. A less risky portfolio would contain a large portion of savings in assets such as CDs and high-

As described in the previous section, a tradeoff between risk and return exists, where riskier assets typically offer a greater average return. This choice between risk and return not only affects one’s personal investments, but also affects how one goes about saving for the future and for retirement, which we discuss next.

Saving for the Future: Employer-Based Programs

Upon graduating from college, among the exciting challenges facing the new graduate is seeking a good job and earning a salary that, hopefully, allows for a more comfortable life. But besides earning more money, decisions must be made about how to save for the future.

Suppose you find your dream job and begin work. Besides the Social Security (FICA) tax that is taken out of each paycheck to fund retirement benefits, you are asked whether you want to contribute to your employer’s retirement program. Do you contribute, and if so, how much? 3%? 6%? More? And once you contribute to an account, in what type of assets do you invest that money? Safe or risky assets, or some combination? The tradeoff between risk and return becomes a very important factor in these decisions.

Let’s begin by looking at employer-

To Contribute or Not to Contribute? Most retirement savings programs allow (or in some cases, require) employees to contribute a certain percentage of their wage earnings into a retirement account. Many companies will then offer a full or partial match of the contribution up to 3% to 4% of one’s salary.

vesting period The minimum number of years a worker must be employed before the company’s contribution to a retirement account becomes permanent.

If your employer offers to match savings contributions, this is essentially “free money” that gets added to your savings, dramatically increasing your return as long as you satisfy the vesting period, the minimum years of employment required for the employer-

Suppose you contribute $1,000 into the savings program, and your employer matches it with another $1,000. You will have instantly earned a 100% return on your investment as long as the vesting period has been satisfied. Try finding another financial asset that offers this high a return!

Another benefit of 401(k) (or similar) programs is that contributions are tax-

Suppose you earn $75,000 in taxable income. This means you are in the 25% tax bracket for most income earned. Suppose you increase your 401(k) contribution by $1,000. How much does your take-

A downside of most retirement plans is the restriction on when you can use the savings. The minimum age for withdrawing money from most 401(k) accounts is 59.5 years. Withdrawing money before this age incurs (with few exceptions) a 10% early withdrawal penalty.

In What Assets Should One Invest? Suppose you have decided to contribute to your employer’s retirement plan and to take advantage of the employer match and tax benefits. Now you are given online access to your account, where you see many options on where to invest your money.

As with all investments, risk assessment is an important consideration when it comes to managing retirement accounts. Most accounts allow you to choose a portfolio of investments ranging from safe assets (such as Treasury bills) to risky assets (such as high-

Between October 2007 and March 2009, major stock market indexes fell by nearly 50%. Retirement accounts that were invested fully in stocks fell drastically in value. This had devastating effects on older workers who had not transitioned to safer assets as they approached retirement. However, for younger workers, stock market drops tend to have minimal effects in the long run. In fact, temporary dips in the stock market can even improve outcomes over time, as the Issue in this section describes.

Other Retirement Savings Tools: Social Security, Pensions, and IRAs

Besides employer-

Social Security Social Security is another form of retirement savings that nearly every American participates in from the time they start working as a teenager. The payroll tax (FICA) is 12.4% (of which 6.2% is paid by employees and 6.2% is paid by employers) of wage earnings up to a maximum of $118,500 in 2016. Unlike 401(k) contributions, the money you contribute to FICA is not yours, but rather is used to pay the benefits of those currently collecting Social Security benefits. Benefits are determined by a formula based on one’s lifetime contributions.

The minimum age to begin collecting Social Security is 62, though if you wait until age 67, monthly benefits will be greater, and potentially will pay more overall if you live longer. Of course, if you have a family history of shorter lifespans, it might be a good idea to start collecting sooner.

Some have argued that Social Security is unfair to the poor, who generally have lower life expectancies than the rich. If the minimum age for collecting Social Security rises due to a shortfall of funds, those with lower life expectancies might not collect anything (except for a portion that can be bequeathed to a spouse or heir).

pensions A retirement program into which an employer pays a monthly amount to retired employees until they die.

Pension Plans Pensions are an alternative to 401(k)-type accounts. Pensions are monthly payments made by your employer from the day you retire until you die, based on the number of years you worked at the company. For example, a person who worked at a company 30 years might receive a pension of $3,000 per month upon retirement for the rest of his or her life, while someone who worked only 10 years might receive $1,000 per month.

ISSUE

Can a Stock Market Crash Increase Long-

From October 2007 to March 2009, major U.S. stock market indices (Dow, NASDAQ, and S&P 500) fell by more than 50% from their peaks. Investment savings accounts that took decades to accumulate saw their values drop in half in less than 17 months. The same was true for many retirement accounts, such as 401(k) and IRA accounts, which often are heavily invested in stocks. Indeed, this was a bleak period to follow one’s retirement savings, not to mention the equally devastating loss in housing values during this period. Would the drop in stock values create long-

Although money invested up to October 2007 suffered a severe decline in value, most workers who continued to contribute to their retirement plans (and with matching employer additions to the new funds), saw their retirement portfolio values bounce back within a few years. How did this happen?

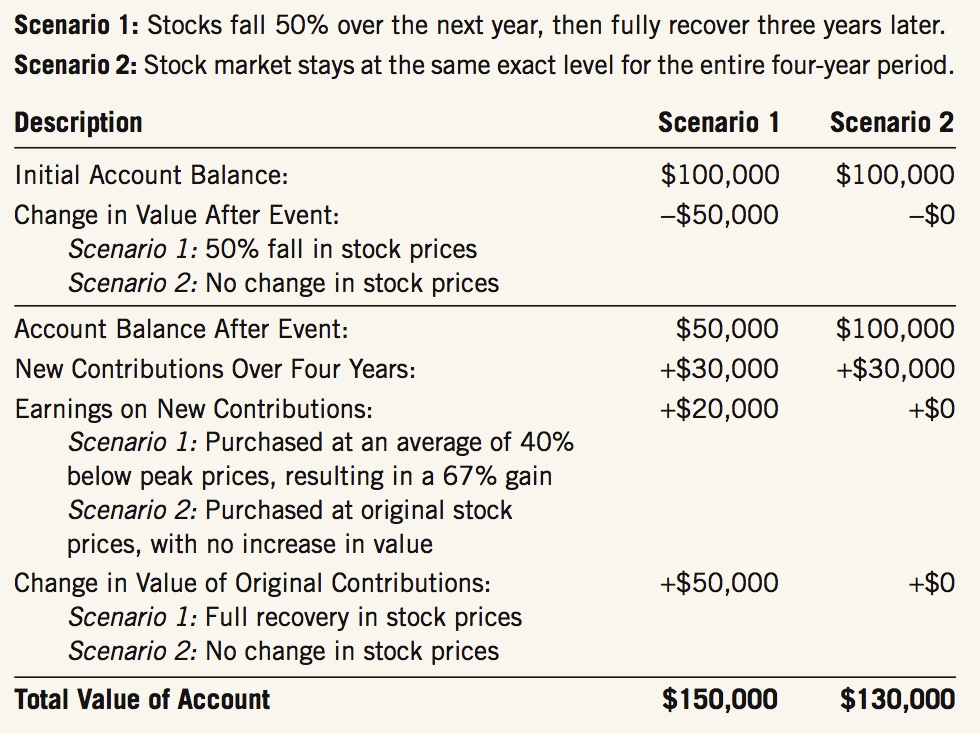

As new money entered retirement plans during the stock market decline, these funds were invested in assets at their new lower prices. When stock values recovered, old funds regained their values, while new funds saw healthy gains in value. The following example illustrates two scenarios using hypothetical numbers.

This hypothetical scenario shows that a drop in the stock market may not cause a major problem for retirement savings over the long run as long as one continues to work and contribute toward retirement. And the younger the worker, the less of an impact short-

Because pension benefits are difficult for companies to predict as people live longer, employers are increasingly switching to fixed-

Finally, in addition to personal savings, investments, 401(k) and pensions plans, many individuals choose to save using individual retirement arrangements (IRAs).

Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs) Similar to 401(k) programs, traditional IRA programs allow one to save pretax (tax-

An alternative to a traditional IRA is a Roth IRA, which allows posttax dollars to be contributed up to a certain limit each year. Why would one contribute posttax dollars as opposed to pretax dollars? First, with a Roth IRA, money that you contribute (but not the earnings on contributions except in certain circumstances) can be withdrawn anytime without penalty. Second, Roth IRAs do not incur any taxes upon withdrawal after age 59.5, including the interest and capital gains the account accumulates over its life. Thus, while one pays taxes upfront on initial contributions, no taxes are paid on earnings, which can be very substantial with compounding.

Saving for the future is an important financial decision. Fortunately, many programs such as 401(k), Social Security, and IRAs make the process easier.

CHECKPOINT

FINANCIAL TOOLS FOR A BETTER FUTURE

Credit cards typically are an expensive way to finance borrowing, even with teaser rates.

Debt and savings rise rapidly over the long run due to the compounding effect.

A tradeoff exists between risk and return: The greater the risk, the higher the average return on investment.

Company-

sponsored retirement accounts such as a 401(k) allow employees to contribute pretax dollars and receive matching company contributions. Social Security is a program into which current contributors (workers) pay for benefits of the recipients (retirees) by way of a payroll tax on wages.

Individual retirement arrangements (IRA) are similar to 401(k) programs except that they are not company sponsored and they provide greater investment choices.

QUESTIONS: Suppose Nicole is very risk averse with her money, while Jose likes to invest in riskier assets in hopes of a higher return. What type of assets would be best suited for each person? Supposing the tradeoff between risk and return holds true over the next 30 years, how would Nicole’s savings compare to Jose’s given the compounding effect (assuming each saves the same amount)?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Because Nicole is more risk averse with her money, she would choose a low-