NEW MONETARY POLICY CHALLENGES

For much of the past century, since the Federal Reserve Act created the Federal Reserve and with it monetary policy, policies were quite predictable and the role of the Fed was seen as an ever-

These perceptions have changed over the past decade after both the United States and Europe experienced the worst financial crisis in nearly a century. Extraordinary times called for extraordinary efforts by the Fed and the ECB, using monetary policy beyond what is used in normal times. In the United States, the recession of 2007–

The Fed: Dealing with an Economic Crisis Not Seen in 80 Years

The financial meltdown that plagued the global economy in the latter part of the last decade was caused by a perfect storm of conditions. First, a world savings glut and unusually low interest rates from 2002 to 2005 led to a housing bubble. Second, financial risk was not properly accounted for, as consumers were eager to buy homes (sometimes second homes) and banks were so eager to lend that they ignored previous lending standards. Third, investors and financial institutions (including pension funds) bought trillions of dollars of assets that depended on housing values increasing consistently in the future.

When the housing bubble collapsed, the house of cards collapsed as well. Falling home values and rising mortgage payments caused homeowners to default, leading to many foreclosures. The foreclosures caused assets dependent on housing values to plummet, resulting in trillions of dollars in losses by financial firms and investors. Banks found themselves in trouble, and the government bailed out the banks by buying up bad loans to provide capital and liquidity in order to prevent bank runs and a sharp fall in lending.

In response to the financial crisis, the Fed used its normal monetary policy tools and some that it hadn’t used since the 1930s. By December 2008 the Fed had lowered its federal funds target rate, using its normal monetary policy tool, to essentially 0%. By this time, the Fed turned to extraordinary measures when it began making massive loans to banks and buying large amounts of risky mortgage-

The Fed was the prime mover in dealing with the financial crisis, once it recognized it. One can argue that it took too long for the Fed to recognize the problem, and the Fed may have encouraged the housing bubble by keeping interest rates very low for too long. Further, the government’s response in bailing out financial institutions and other industries, along with a dramatic increase in the monetary base, led some to believe that the Fed overstepped its authority by exercising powers it did not have (such as its role in buying up troubled assets from banks) and expanding the monetary base too far, risking widespread inflation in the future.

But as former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said, if your neighbor’s house is on fire because he was smoking in bed, you deal with the fire first because if you don’t, your own house can burn down. You deal with your neighbor’s smoking problem later.

The U.S. economy has mostly recovered from the financial crisis, but current Fed Chair Janet Yellen has remained cautious, allowing monetary policy to remain accommodative as economic growth improves.

The Fed was not alone in taking drastic action during the financial crisis. The Fed’s counterpart in Europe, the ECB, took extraordinary action as well.

The Eurozone Crisis and the Role of the European Central Bank

The Eurozone was created during a 1992 meeting in the Netherlands by twelve European nations that envisioned a single currency that would reduce transaction costs and facilitate and expand trade. The meeting resulted in the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, which set the monetary criteria that each member nation had to satisfy before joining the Eurozone. These criteria included, among others:

Maintaining an inflation rate no higher than 1.5% above the average of the three member countries with the lowest inflation

Maintaining long-

term interest rates (on 10- year bonds) no higher than 2% above the average of the three member countries with the lowest interest rates Maintaining annual deficits of less than 3% of GDP

Maintaining total debt of less than 60% of GDP

Having no major currency devaluation in the preceding two years

When the euro was introduced in 1999, eleven of the twelve treaty members met the monetary criteria. Greece took two extra years to satisfy the criteria and was admitted into the Eurozone in 2001.

Why were such stringent criteria needed? When a common currency is adopted, monetary policy becomes shared by all members. Therefore, a monetary crisis in one country can quickly spread to all countries. Germany, the largest and wealthiest member of the Eurozone, traditionally had maintained low inflation and a very stable economy. Although Germany had much to gain from the Eurozone, it also faced risks by integrating its monetary policy with countries whose economies were less stable. Because of Germany’s fear of inflation, the Eurozone was set up in a way that prescribed austerity measures as opposed to monetary expansion as a cure for debt. However, the severity of the Eurozone crisis that would ensue a decade later changed this focus, as even Germany had to accept that extraordinary actions were needed.

Still, for much of the first decade, the euro was a success, with member nations keeping their debt under control while the ECB implemented monetary policy for the entire Eurozone. Moreover, the euro established itself as a major reserve currency, giving it significant clout among world financial institutions.

However, conditions began changing in 2007 when several member nations saw their debts rise, requiring some to sell securities (sovereign debt) on future cash revenues to keep their debt-

From 2008 to 2013, nearly half of the Eurozone nations faced some sort of financial crisis. In each situation, the ECB used its normal monetary policy tools in addition to extraordinary measures to lessen the economic impact of the crisis and to prevent nations from defaulting on their debt. A summary of key events faced by individual Eurozone members follows.

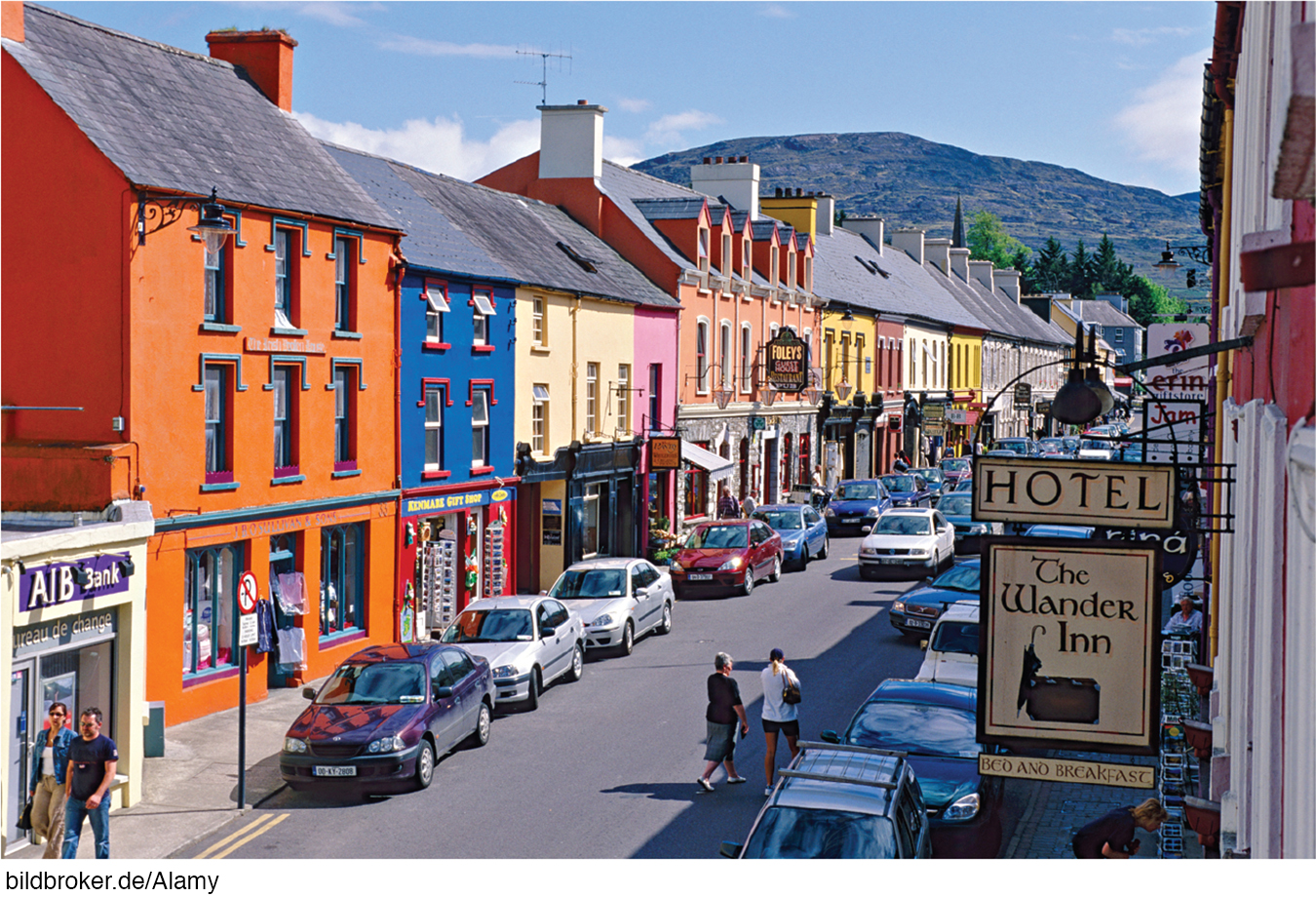

Ireland: Ireland was one of the first member nations to face difficulties when its property bubble burst, causing all of its major banks to face insolvency in 2008. This led the Irish government to pass a law guaranteeing all bank deposits and the ECB to step in and lend billions of euros to Irish banks, an action that up to that point had never been taken on this scale.

Greece: The global recession devastated Greece’s shipping industry, which led to deficits and then a debt crisis in 2010. By 2012 interest rates had risen to over 25%. Further, public riots threatened Greece’s ability to maintain public support for the euro and the conditions required to remain in the Eurozone. A series of bailout packages from the ECB and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) helped bring interest rates down, but unemployment remained high even in 2016. Moreover, citizens in Greece increasingly grew wary of debt-

cutting measures and structural reforms that made life increasingly difficult. Portugal: The third country to receive a bailout package from the ECB in exchange for promises of budget cuts and structural reforms was Portugal, in 2011. The crisis increased unemployment, which had reached 18% by 2013. However, improved economic conditions since then allowed Portugal to exit the bailout program in 2014 and return to mostly normal times, though the effects of the crisis still linger in some parts of the country.

Cyprus: In 2013 Cyprus became the fourth nation to receive a bailout package when heavy investments by investors and banks in private Greek industries went sour. It also became the first nation to borrow funds from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), created by the ECB in September 2012 to provide loans to Eurozone members facing financial difficulties. Like Portugal, Cyprus improved its economy, allowing it to conclude its bailout program in 2016.

Spain: Spain had faced an unrelenting economic crisis since 2008, as uncontrolled debt and unemployment led to many leadership changes. In 2013 the unemployment rate reached 25%, and throughout this period, the ECB bought Spanish government bonds and made extraordinary amounts of loans (around 350 billion euros) to Spanish banks, including new loans from the ESM. But unlike the countries discussed earlier, Spain never accepted a bailout, and strong economic growth in 2015 and 2016 (fueled by record tourism) has put Spain on a path to recovery.

Page 658Italy: Italy has long had a high debt-

to- GDP ratio, even before the crisis in other countries began. It has taken many steps to reduce its debt, which has stood over 100% of its GDP for much of the past decade, though much work remains. A key obstacle facing Italy has been the lack of economic growth. While other Eurozone nations experienced economic growth following the global economic crisis, Italy remained in a recession for several more years, and today remains among the slowest growing economies in the Eurozone. Slovenia: In 2007 Slovenia became the 13th member of the Eurozone. Slovenia’s economy is considerably smaller than the rest of the Eurozone, and banks were never fully privatized, resulting in political influences in banking decisions. These factors made Slovenia more prone to economic downturns, and led to its financial crisis. Fortunately, a strong rise in exports and successful reforms of state-

owned companies led to healthy economic growth since 2013, setting a positive example of how good economic policy can resolve financial crises quickly.

In sum, the ECB took extraordinary actions that it had never taken in its history to prevent financial crises in individual countries from causing the collapse of the Eurozone. First, the ECB provided loans to banks and bought government debt, and created the ESM in 2012 to manage funds being disbursed. Second, the ECB negotiated deals with private banks and other investors to write off portions of debt and to restructure existing loans to governments. Third, it demanded that governments pass austerity measures, enact structural reforms, and be subjected to greater scrutiny. Like the Fed, the ECB’s balance sheet ballooned during the crisis, from about 1 trillion euros in 2007 to over 3 trillion euros in 2012. Why was the ECB so eager to take extraordinary actions to prevent countries from defaulting on their debt?

ISSUE

The Challenges of Monetary Policy with Regional Differences in Economic Performance

The Eurozone crisis of 2008–

Although each member nation would have representation in the ECB based on population, Germany and France, the two largest members, dominate decisions. The challenge faced by the ECB is formulating a common monetary policy that best fits the economic conditions faced by its members. This is not easy.

When one part of the Eurozone is booming (say, Ireland) and would benefit from contractionary monetary policy, while another is struggling with debt (Greece) and requires expansionary monetary policy, choosing a common monetary policy involves placing the priority of one country’s economic concerns over another.

But is the situation in Europe the only one in which a common monetary policy needs to address wide variations in economic performance? The answer is no, and the best example of another monetary zone facing similar problems may surprise you . . . the United States.

The United States shares many similarities with the Eurozone when it comes to monetary policy. Although the United States is one country, wide variations in economic performance still exist. In 2015 Delaware’s per capita income of about $72,000 was twice that of Mississippi’s $36,000.

Further, U.S. monetary policy also must take into account territories that use the U.S. dollar, such as Puerto Rico, as well as countries such as Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama, all of which have a per capita income even lower than Mississippi’s. The Fed’s decisions have a direct impact on all economies that use the U.S. dollar.

In sum, large monetary unions such as the Eurozone and the United States must weigh the priorities of one region against another when considering the policies they implement. Such a task makes the statement that monetary policy is as much art as science a realistic description facing central banks today.

Clearly, the number of Eurozone nations facing a financial crisis had reached a critical point by 2013. If any nation defaults and pulls out of the Eurozone, it could trigger a global loss of confidence in the euro. For example, investors might be less willing to invest in euro-

However, the ECB used aggressive monetary policies to reduce the likelihood of a nation’s exit from the Eurozone. Just as the Fed stepped in to prevent regional crises in the United States by injecting financial capital and reducing interest rates, the ECB used expansionary monetary policies to help member nations facing economic crises. This is much easier said than done, as the Issue described, when different areas of a currency zone face varying levels of economic performance.

Why Would a Country Give Up Its Monetary Policy?

What factors led Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama to give up their ability to use monetary policy in favor of adopting the U.S. dollar?

One of the first tasks when traveling abroad is to exchange currency. In most countries, this is an easy task: Just visit a foreign exchange booth or withdraw money from a local ATM. Some countries that depend on tourism, such as Jamaica and Costa Rica, readily accept U.S. dollars despite having their own national currency. But for American tourists visiting Ecuador, El Salvador, or Panama, exchanging money isn’t even an option, because the official currency in these countries is the U.S. dollar.

Why would a country adopt the U.S. dollar as its official currency, and what effect does it have on monetary policy?

The decision for a country to use a foreign currency (in this case, the U.S. dollar) as its own official currency, called dollarization, is not in any way influenced or dictated by the United States. Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama willingly gave up their own currency to adopt the U.S. dollar. And by doing so, these countries relinquished their ability to set monetary policy, because the supply of dollars and the interest rate are managed by the U.S. Federal Reserve. Why would a country give up control of its monetary policy?

Panama adopted the U.S. dollar over a century ago to facilitate trade, given its strategic geographic location that attracts cargo ships from around the world crossing the Panama Canal. In the case of Ecuador and El Salvador, which adopted the U.S. dollar in 2000 and 2001, respectively, their situations were different than Panama’s. Prior to adopting the U.S. dollar, both countries had rampant inflation, caused by the inability of their central banks to keep money growth under control. High inflation decreases investor confidence because profits quickly lose their value. By adopting the U.S. dollar (and thereby preventing the government from adjusting the money supply), Ecuador and El Salvador sent a signal that they were serious about maintaining low inflation, which subsequently led to greater foreign direct investment.

Still, problems persist in countries that dollarize, and the lack of an independent monetary policy makes it difficult to address fluctuations in the economy, especially when they differ from those of the United States. But for these countries and others that have dollarized their economies, the potential benefits outweigh the costs.

Today, most of the Eurozone countries that faced financial crises have recovered with some countries such as Ireland and Slovenia experiencing rapid economic growth. The exception is Greece, which continued to face challenges in 2016. But overall, economic growth remains tenuous throughout the region. This is not unlike the recovery pattern experienced in the United States.

In the United States, the housing market has mostly recovered, employment growth has been strong, stock markets have set new highs, and banks have strengthened their balance sheets. Still, as in Europe, problems such as deficits and weak growth remain, which means that the Fed will continue to rely on monetary tools to prevent problems from home and abroad from engulfing the economy.

The next chapter is devoted to analyzing the major macroeconomic policy challenges involving both fiscal policy and monetary policy, allowing you to use the macroeconomic tools learned thus far to sketch out solutions.

CHECKPOINT

NEW MONETARY POLICY CHALLENGES

To control the financial panic of 2008, the Fed used its normal monetary policy tools and some that it hadn’t used in many decades.

The European Central Bank is the Fed’s counterpart in Europe, setting the monetary policy for the nineteen-

member Eurozone. A long and severe debt crisis occurred when several European nations neared default on their loans, requiring extraordinary actions, including bailout loans, by the ECB to keep the effects of the crisis from spreading to the entire Eurozone.

QUESTION: The collapse of the financial markets in late 2008 resulted in the Fed reducing interest rates to near 0%. Was it likely that the U.S. economy in 2009 sank into a Keynesian liquidity trap?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Reducing interest rates to low levels to stimulate credit and the economy was probably not sufficient by itself. But as consumer spending dropped off, businesses avoided new investments as markets declined or disappeared, suggesting that the economy may have been in a liquidity trap. Keynesian analysis got the nod from policymakers with the $787 billion fiscal stimulus package passed in 2009.