THE GAINS FROM TRADE

Economics studies voluntary exchange. People and nations do business with one another because they expect to gain through these transactions. Foreign trade is nearly as old as civilization. Centuries ago, European merchants were already sailing to the Far East to ply the spice trade. Today, people in the United States buy cars from South Korea and electronics from China, along with millions of other products from countries around the world.

autarky A country that does not engage in international trade, also known as a closed economy.

imports Goods and services that are purchased from abroad.

exports Goods and services that are sold abroad.

Virtually all countries today engage in some form of international trade. Those that trade the least are considered closed economies. A country that does not trade at all is called an autarky. Most countries, however, are open economies that willingly and actively engage in trade with other countries. Trade consists of imports, goods and services purchased from other countries, and exports, goods and services sold abroad.

Many people assume that trade between nations is a zero-

To understand how this works, and thus why nations trade, we need to consider the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage. Note that nations per se do not trade; individuals in specific countries do. We will refer to trade between nations but recognize that individuals, not nations, actually engage in trade.

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

absolute advantage One country can produce more of a good than another country.

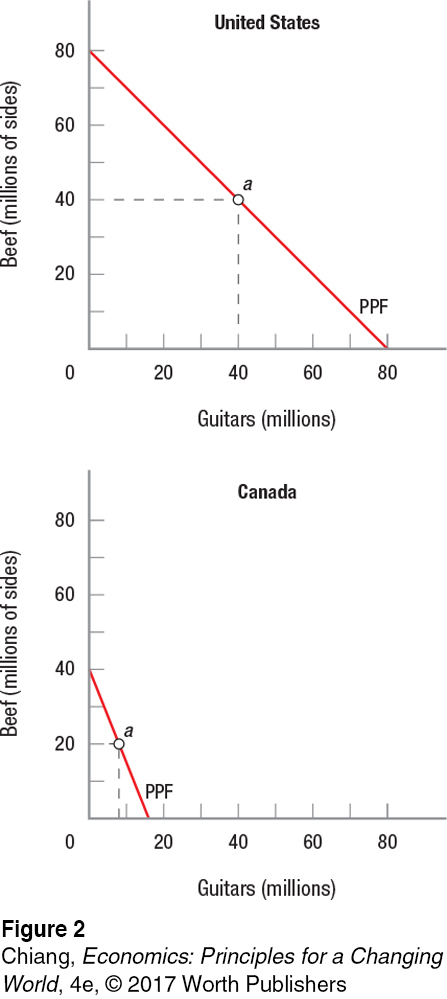

Figure 2 shows hypothetical production possibilities frontiers for the United States and Canada. For simplicity, both countries are assumed to produce only beef (measured as a “side”, which is half of a steer) and guitars. Given the production possibility frontiers (PPFs) in Figure 2, the United States has an absolute advantage over Canada in the production of both products. An absolute advantage exists when one country can produce more of a good than another country. In this case, the United States can produce twice as much beef and 5 times as many guitars as Canada. This is not to say that Canadians are inefficient in producing these goods, but rather that Canada does not have the resources to produce as many goods as the United States does (for one thing, its population is barely a tenth the size of that of the United States).

At first glance, we may wonder why the United States would be willing to trade with Canada. If the United States can produce so much more of both goods, why not just produce its own beef and guitars? The reason lies in comparative advantage.

comparative advantage One country has a lower opportunity cost of producing a good than another country.

One country enjoys a comparative advantage in producing some good if its opportunity costs to produce that good are lower than the other country’s. In this example, Canada’s comparative advantage is in producing beef. As Figure 2 shows, the opportunity cost for the United States to produce another million sides of beef is 1 million guitars; each added side of beef essentially costs 1 guitar.

Contrast this with the situation in Canada. For every guitar Canadian manufacturers forgo making, they can produce 2.5 more sides of beef. This means a side of beef costs only 0.4 guitar in Canada (1/2.5 = 0.4). Canada’s comparative advantage is in producing beef, because a side of beef costs 0.4 guitar in Canada, while the same side of beef costs an entire guitar in the United States. By the same token, the United States has a comparative advantage in producing guitars: 1 guitar in the United States costs 1 side of beef, but the same guitar in Canada costs 2.5 sides of beef.

Table 1 summarizes the opportunity costs of each good in each country and shows which country has the comparative advantage for each good. These relative costs suggest that the United States should focus its resources on guitar production and that Canada should specialize in beef.

| TABLE 1 | COMPARING OPPORTUNITY COSTS FOR BEEF AND GUITAR PRODUCTION | |||

| U.S. Opportunity Cost | Canada Opportunity Cost | Comparative Advantage | ||

| Beef production | 1 guitar | 0.4 guitar | Canada | |

| Guitar production | 1 side of beef | 2.5 sides of beef | United States | |

Gains from Trade

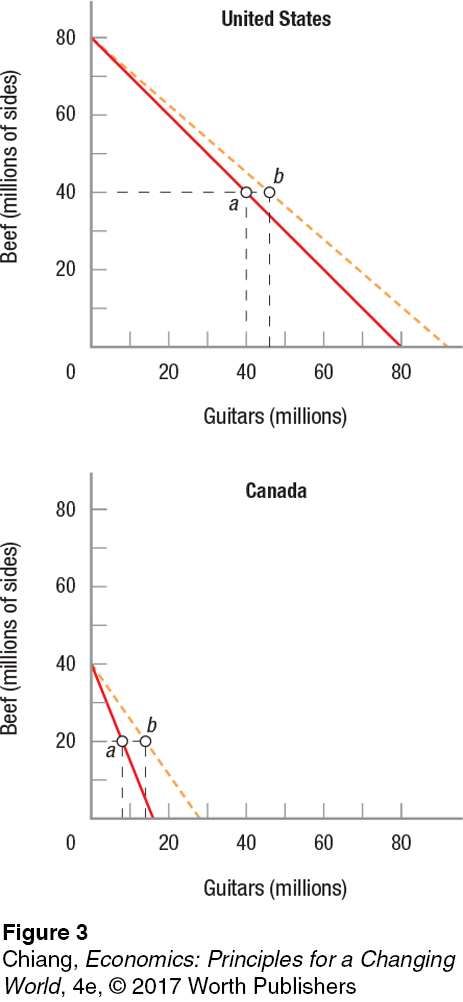

To see how specialization and trade can benefit both countries even when one has an advantage in producing more of both goods, assume that the United States and Canada at first operate at point a in Figure 2, producing and consuming their own beef and guitars. As we can see, the United States produces and consumes 40 million sides of beef and 40 million guitars. Canada produces and consumes 20 million sides of beef and 8 million guitars. This initial position is similarly shown as points a in Figure 3.

Assume now that Canada specializes in producing beef, producing all that it can—

Thus, the United States is producing 20 million sides of beef and 60 million guitars. Canada is producing 40 million sides of beef and no guitars. The combined production of beef remains the same, 60 million, but guitar production has increased by 12 million (from 48 million to 60 million).

The two countries can trade their surplus products and will be better off. This is shown in Table 2. Assuming that they agree to share the added 12 million guitars between them equally, Canada will trade 20 million sides of beef for 14 million guitars. Points b in Figure 3 show the resulting consumption patterns for each country. Each consumes the same quantity of beef as before trading, but each country now has 6 million more guitars: 46 million for the United States and 14 million for Canada. This is shown in the last column of the table.

| TABLE 2 | THE GAINS FROM TRADE | |||

| Country and Product | Before Specialization | After Specialization | After Trade | |

| United States | ||||

| Beef | 40 million | 20 million | 40 million | |

| Guitars | 40 million | 60 million | 46 million | |

| Canada | ||||

| Beef | 20 million | 40 million | 20 million | |

| Guitars | 8 million | 0 | 14 million | |

One important point to remember is that even when one country has an absolute advantage over another, countries still benefit from trade. The gains are small in our example, but they will grow as the two countries approach one another in size and their comparative advantages become more pronounced.

Practical Constraints on Trade At this point, we should take a moment to note some practical constraints on trade. First, every transaction involves costs. These include transportation, communications, and the general costs of doing business. Over the last several decades, however, transportation and communication costs have declined all over the world, resulting in growing world trade.

Second, the production possibilities frontiers for nations are not linear; rather, they are governed by increasing costs and diminishing returns. Countries find it difficult to specialize only in one product. Indeed, specializing in one product is risky because the market for the product can always decline, new technology might replace it, or its production can be disrupted by changing weather patterns. This is a perennial problem for developing countries that often build their exports and trade around one agricultural commodity.

Although it is true that trading partners benefit from trade, some individuals and groups within each country may lose. Individual workers in those industries at a comparative disadvantage are likely to lose their jobs, and thus may require retraining, relocation, or other help if they are to move smoothly into new occupations.

ISSUE

The Challenge of Measuring Imports and Exports in a Global Economy

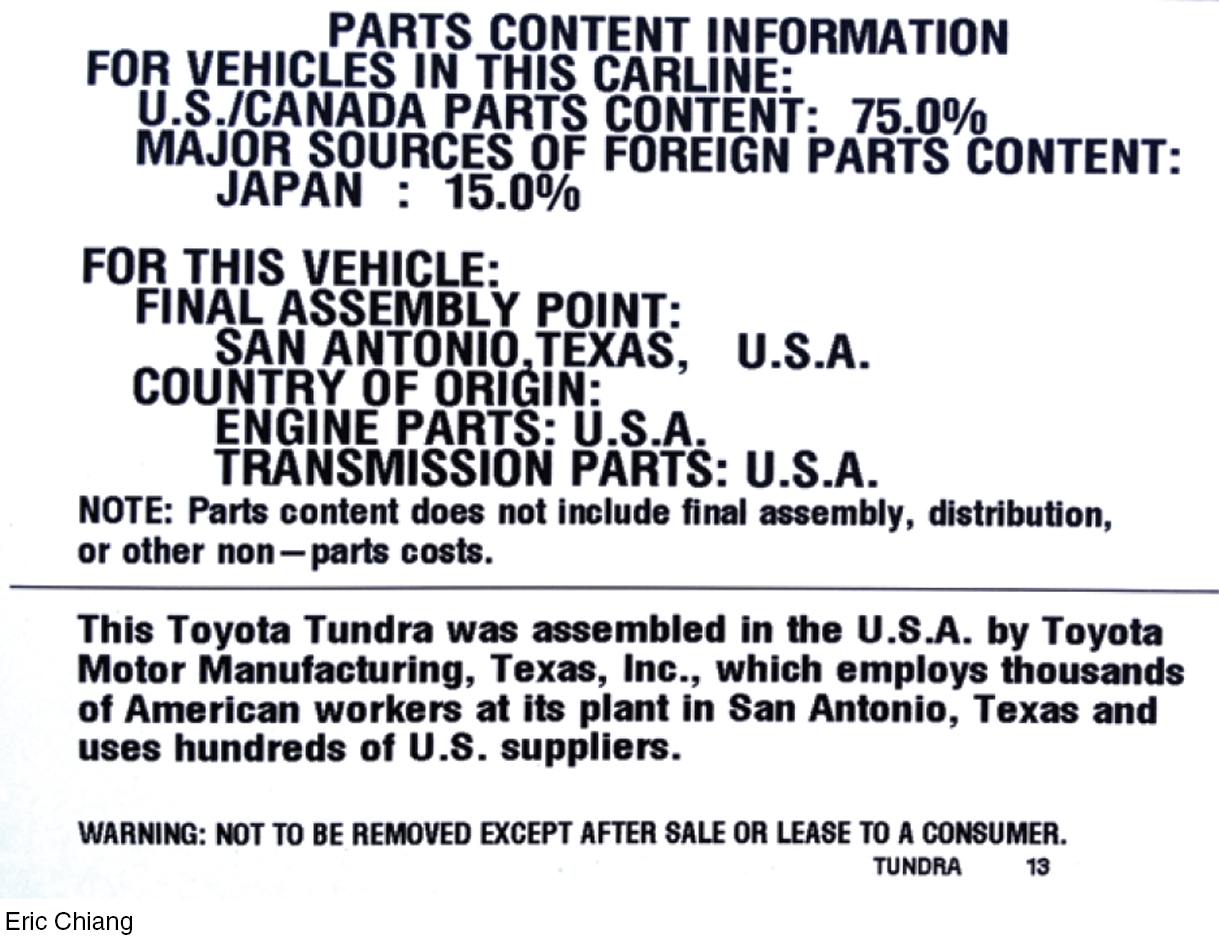

Before the growth of globalization of manufacturing, the brand names of products would indicate their origin. For example, Sony televisions were made in Japan, Nokia telephones were made in Finland, and a Ford car would be made in the United States using American steel, engines, cloth, and, of course, American labor.

Today, a product’s brand name does not tell the entire story. Production has become very complex, with parts sourced from around the world. With such complexities in trade, how then are imports and exports measured?

Do sales of Levi’s jeans count as U.S. exports? Although Levi’s are an American brand that has for much of its history been produced in the United States, today nearly all Levi’s jeans are made in Asia. Therefore, the American-

In order to measure imports and exports accurately, the United States Bureau of Economic Analysis tabulates data from documents collected by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which details the appraised value (price paid) for all shipments of goods into and out of the ports of entry (whether by land, air, or sea). The value of imported and exported services is more difficult to measure, and is based on a survey of monthly government and industry reports to determine the value of all services bought from and sold to foreigners.

The globalized economy has been spurred in large part by falling transportation and communication costs in the past few decades. Companies face ever greater competition, applying more pressure to reduce production costs. The expansion of the production process to a worldwide factory is just one way our economy has changed, and this trend is likely to continue into the future.

When the United States signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico, many U.S. workers experienced this sort of dislocation. Some U.S. jobs went south to Mexico because of lower wages. States such as Texas and Arizona experienced greater levels of job dislocation due to their proximity to Mexico. Still, by opening up more markets for U.S. products, NAFTA has stimulated the U.S. economy. The goal is that displaced workers, newly retrained, will end up with new and better jobs, although there is no guarantee this will happen.

CHECKPOINT

THE GAINS FROM TRADE

An absolute advantage exists when one country can produce more of a good than another country.

A comparative advantage exists when one country can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another country.

Both countries gain from trade when each specializes in producing goods in which they have a comparative advantage.

Transaction costs, diminishing returns, and the risk associated with specialization all place some practical constraints on trade.

QUESTIONS: When two individuals voluntarily engage in trade, they both benefit or the trade wouldn’t occur—

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Yes, in general, nations would not trade unless they benefit. However, as we have seen, even though nations as a whole gain, specific groups—