PRICE CEILINGS AND PRICE FLOORS

laissez-

To this point, we have assumed that competitive markets are allowed to operate freely, without any government intervention. Economists refer to freely functioning markets as laissez-

However, as we saw at the end of the previous section, sometimes freely functioning markets fail to achieve the optimal quantity of goods and services. An example of this is when many people consider the equilibrium price to be unfair. Because of these economic (efficiency) or political (equity) reasons, governments will sometimes intervene in the market by setting limits on the prices of various goods and services. Governments use price ceilings and price floors to keep prices below or above market equilibrium. What really happens when government sets prices below or above market equilibrium? The previous section hinted at the answer. Let’s look at price ceilings and floors more closely.

Price Ceilings

price ceiling A maximum price established by government for a product or service. When the price ceiling is set below equilibrium, a shortage results.

When the government sets a price ceiling, it is legally mandating the maximum price that can be charged for a product or service. This is a legal maximum; regardless of market forces, price cannot exceed this level. An historical example of a price ceiling is the establishment of rent-

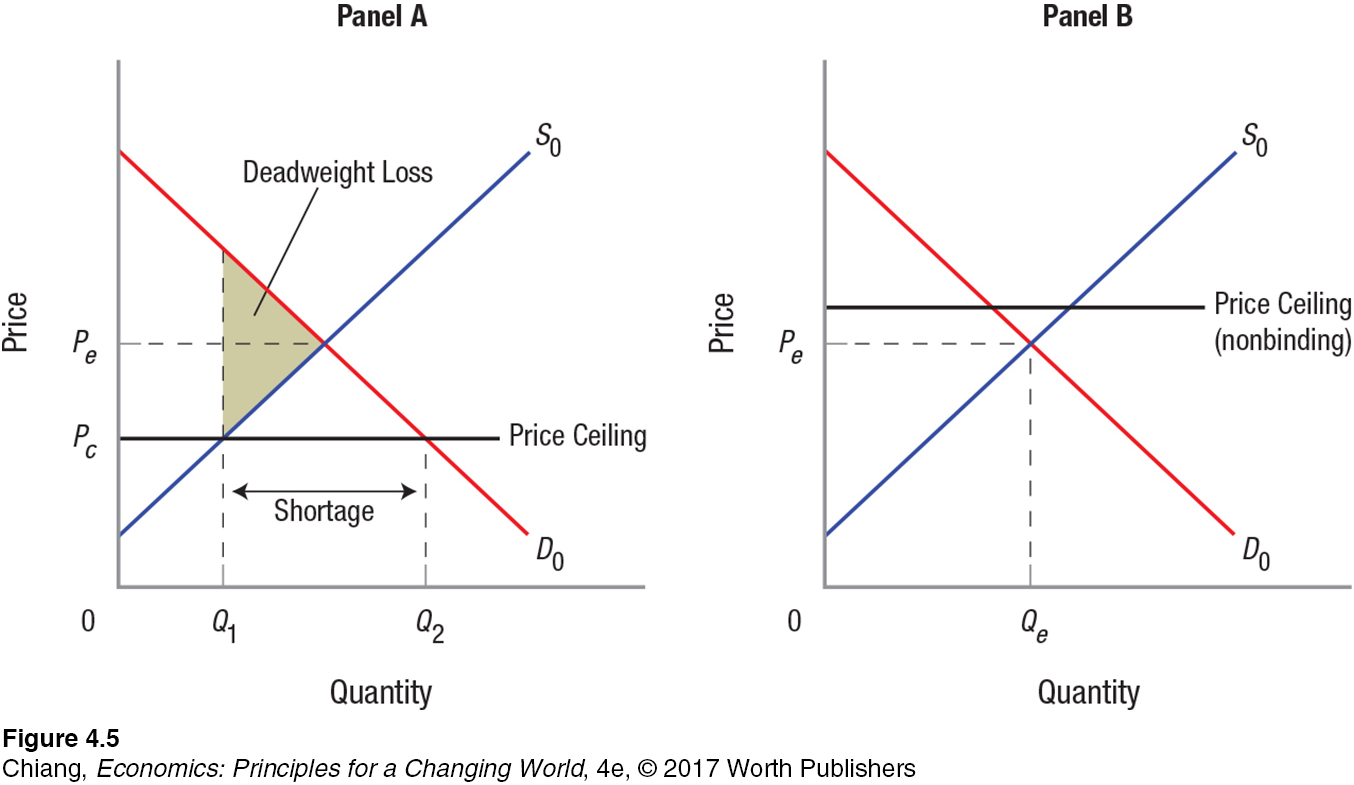

Panel A in Figure 5 shows an effective price ceiling, or one in which the ceiling price is set below the equilibrium price. In this case, equilibrium price is Pe, but the government has set a price ceiling at Pc. Quantity supplied at the ceiling price is Q1, whereas consumers want Q2; therefore, the result is a shortage of Q2 – Q1 units of the product. As we saw in the previous section, setting a price below equilibrium alters consumer and producer surplus and results in a deadweight loss indicated by the shaded area. If the price ceiling is raised toward equilibrium, the shortage is reduced along with the deadweight loss. If the price ceiling is set above Pe (as shown in panel B), the market simply settles at Pe, and the price ceiling has no impact; it is nonbinding, and no deadweight loss occurs. A price ceiling can also become nonbinding if market factors cause supply to increase or demand to fall, pushing the equilibrium price below the ceiling.

A common mistake when analyzing the effect of price ceilings is assuming that effective price ceilings appear above the market equilibrium, because the word “ceiling” refers to something above you. Instead, think of ceilings as something that keep you from moving higher. Suppose you build a makeshift skateboarding ramp in your apartment hallway, and tempt your friends to test it out. If the ceiling is too low, some of your friends might end up with a severe headache. In other words, an effective (binding) ceiling is one that is kept lower than normal. If the ceiling can be raised by 5 feet, then all of your friends would achieve their jumps without bumping their heads. In sum, price ceilings have their strongest effects when kept very low; as the ceiling is raised, the effect of the policy diminishes, and the ceiling becomes nonbinding once the equilibrium price is reached.

Given the price ceiling, one might argue that although shortages might exist, at least prices will be kept lower and therefore more “fair.” The question is, fairer to whom? Suppose your university places a new price ceiling on the rents of all existing apartments located on campus, one that is below the rents of similar apartments off campus. This might sound like a great idea, but often what sounds like a great idea comes with costs.

misallocation of resources Occurs when a good or service is not consumed by the person who values it the most, and typically results when a price ceiling creates an artificial shortage in the market.

A price ceiling increases the quantity demanded for on-

Besides the misallocation of resources and potential opportunity costs of long waits and search costs, price ceilings also lead to some unintended long-

The key point to remember here is that price ceilings are intended to keep the price of a product below its market or equilibrium level. When this happens, consumer surplus increases for those able to purchase the good, while producer surplus falls. The ultimate effect of a price ceiling, however, is that the quantity of the product demanded exceeds the quantity supplied, thereby producing a shortage of the product in the market. When shortages occur, deadweight losses are created because some mutually beneficial transactions do not take place, causing a reduction in total surplus.

Price Floors

price floor A minimum price established by government for a product or service. When the price floor is set above equilibrium, a surplus results.

A price floor is a government-

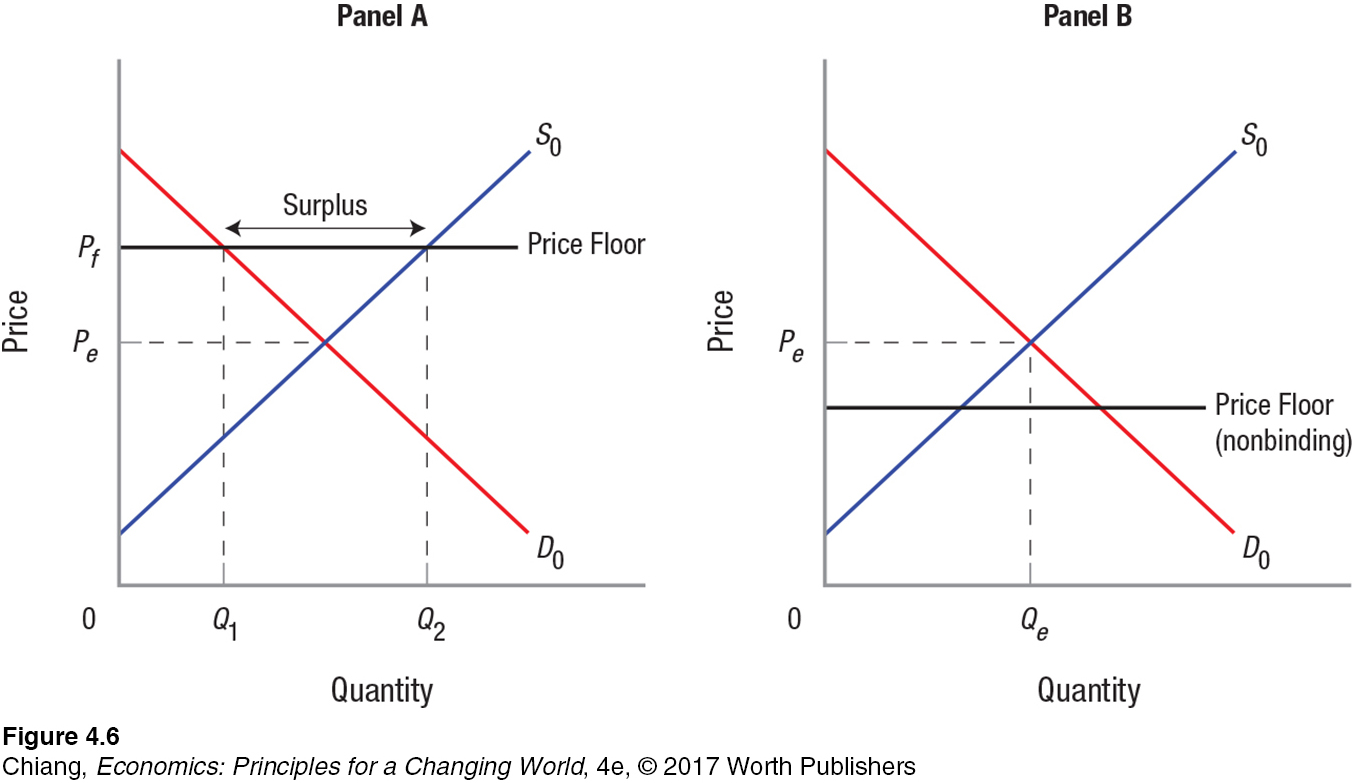

Figure 6 shows the economic impact of a price floor. In panel A, the price floor, Pf, is set above equilibrium, Pe, resulting in a surplus of Q2 – Q1 units. At price Pf, businesses want to supply more of the product (Q2) than consumers are willing to buy (Q1), thus generating a surplus. Depending on the government policy in place with the price floor, producers may end up having to store the excess supply if only Q1 is transacted in the market, or in some cases the government may buy the surplus goods. Either way, inefficiency is created in the market. However, if the price floor is set below equilibrium (as shown in panel B), the equilibrium price, Pe, will prevail in the market. Therefore, a price floor set below Pe has no impact on the market and no deadweight loss occurs. Likewise, a price floor can become nonbinding if market factors push the equilibrium price above the price floor.

Throughout much of the past century, the U.S. government has used agricultural price supports (price floors) in order to smooth out the income of farmers, which often fluctuates due to wide annual variations in crop prices. This approach is not limited to the United States. Many developed countries, including members of the European Union and Japan, have long protected their agriculture industries by ensuring a minimum price level for many types of crops.

ISSUE

Are Price Gouging Laws Good for Consumers?

During the summer hurricane season, residents along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts brace for hurricanes that can wreak havoc on the unprepared. The routine is well known: Buy plywood and shutters to protect windows; fill up gas tanks in cars and buy extra gas for generators; and stock up on batteries, bottled water, and nonperishable foods. Because of the huge spike in demand, numerous states have introduced price gouging laws, which prevent stores from raising prices above the average price of the past 30 days. Penalties for violating such laws are severe.

Price gouging laws generally pass with huge majority votes from both major political parties. The logic seems clear—

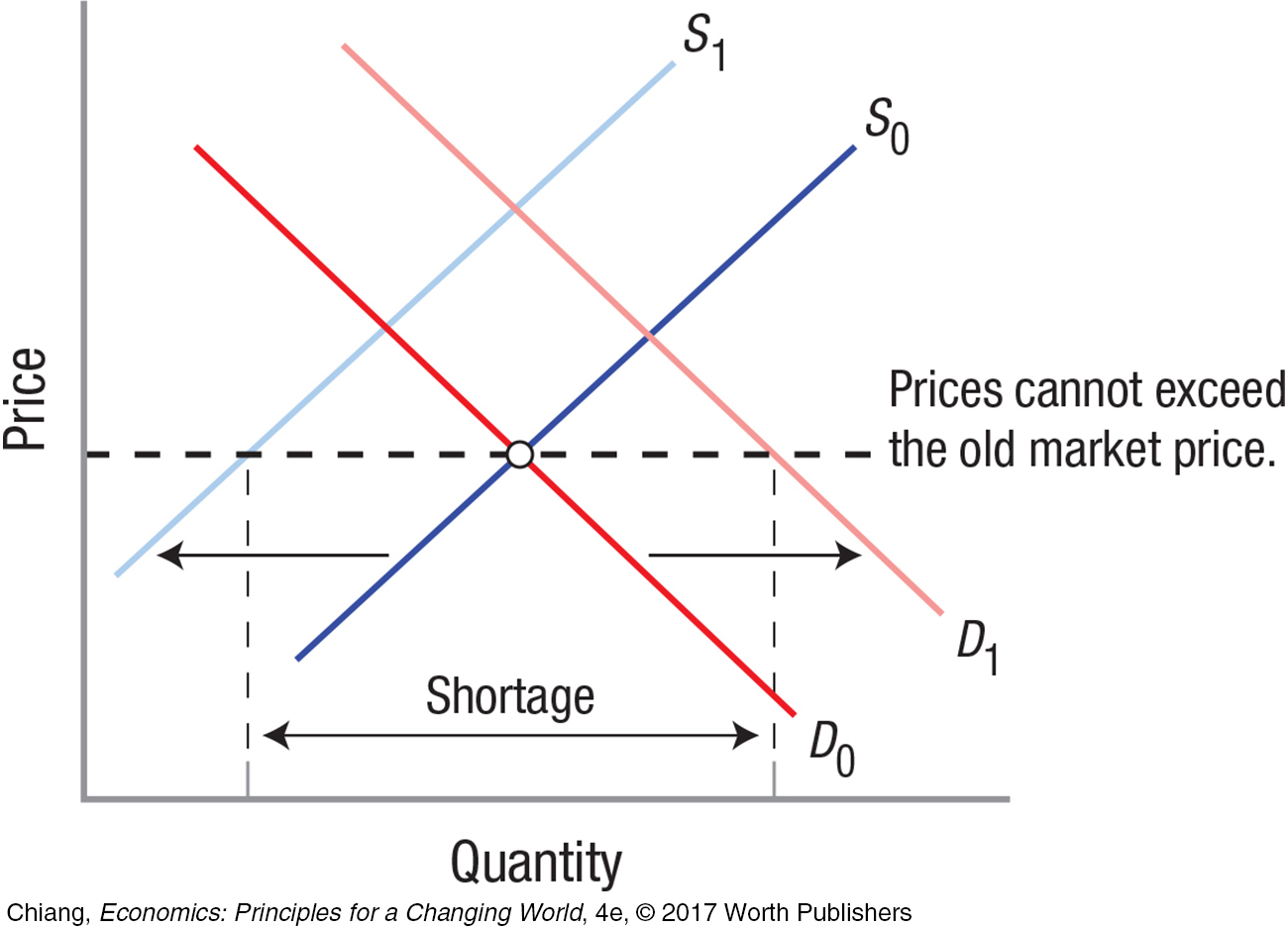

Price gouging laws are price ceilings placed at the price last existing when times were normal. But during a natural disaster, the market is far from normal—

What happens during a shortage? Huge lines form at home improvement stores, gas stations, and grocery stores. Time spent waiting in line is time that could be spent completing other tasks in preparation for the storm. What might be a better solution?

Instead of capping prices and causing a shortage, efforts can be made to provide incentives to businesses to generate more supply. If supply shifts enough to the right to compensate for the increase in demand, then prices need not increase, regardless of the price ceiling. But the question is, How do we incentivize supply? Subsidies to offset increased transportation costs might be an example. Imagine how many supplies could be flown in on a single jumbo jet cargo plane from a non–

These price supports act very much as they are intended. By ensuring a minimum price for a crop, farmers have an incentive to grow more of these crops relative to crops that aren’t protected by price supports. Further, because the price supports typically are above market equilibrium prices, resulting in higher prices for consumers, demand for such crops is less than what it would be without the supports.

Thus, with greater supply and smaller demand, price supports lead to surpluses of crops. What happens to these surpluses? Because the government guarantees the price levels of the crops, it must purchase the excess supply, which is typically stored for use in the event of future shortages. But agricultural surpluses eventually rot, which means government must find other ways to use the surplus before it goes bad. One common use of surplus foods is in public school lunches, leading to some criticism that the types of foods being provided (wheat, grains, and corn) are not the most nutritious foods for children to eat.

Another criticism of agricultural price supports comes from developing countries that depend on agricultural exports for their economic output. These countries claim that price supports hamper their economic development by preventing them from selling goods in which they have a comparative advantage. In other words, agricultural price supports restrict gains from trade.

Despite their questionable economic justification, political pressures have ensured that agricultural price supports and related programs still command a sizable amount of the discretionary domestic federal budget.

Price floors are also used to analyze minimum wage policy. To the extent that the minimum wage is set above the equilibrium wage, unemployment—

In sum, price ceilings and price floors often are policies aimed at promoting equity or fairness in a society, such as preventing rapid price increases for consumers or ensuring fair wages for workers. Still, governments must be careful when setting price ceilings and price floors to avoid meddling with markets.

CHECKPOINT

PRICE CEILINGS AND PRICE FLOORS

Governments use price floors and price ceilings to intervene in markets.

A price ceiling is a maximum legal price that can be charged for a product. Price ceilings set below equilibrium result in shortages.

A price floor is the minimum legal price that can be charged for a product. Price floors set above market equilibrium result in surpluses.

QUESTION: The day after Thanksgiving, also known as Black Friday, is a day on which retailers advertise very steep discounts on selected items such as televisions or laptops. Assuming the number of units available at the discounted price is limited, in what ways are the effects of this pricing strategy similar to a price ceiling set by the government? In what ways do they differ?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of the chapter.

Black Friday specials are typically deeply discounted in order to attract customers into the store, which is why such specials are prominently shown on the first page of sales circulars. Like a price ceiling that is set below the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded for the discounted good increases, while stores limit the number of units available for sale, creating a shortage. Some buyers will be fortunate to find units available to purchase, while subsequent shoppers will find that the product has sold out. Deadweight loss is generated because some customers who would have been willing to pay a little more are unable to purchase the good. However, unlike with a price ceiling, stores strategically choose to advertise goods with many alternatives, such as different brands of televisions and laptops, so that when the discounted product sells out, customers may consider buying a nondiscounted product. Therefore, the pricing strategy leads to a strategic shortage that is designed to attract customers into the store to buy goods in addition to those that are advertised.