MONOPOLY MARKETS

222

monopoly A one-

The very word “monopoly” almost defines the subject matter: a market in which there is only one seller. For example, when you want to watch professional basketball, you will probably watch an NBA or WNBA game. If you pay a monthly water bill, it’s likely that you do not have a choice of which company services your apartment or house. Economists define a monopoly as a market sharing the following characteristics:

The market has just one seller—

one firm is the industry. This contrasts sharply with the competitive market, where many sellers comprise the industry. No close substitutes exist for the monopolist’s product. Consequently, buyers cannot easily substitute other products for that sold by the monopolist. In communities with only one electricity provider, one could install solar panels, but such options are often prohibitively expensive.

A monopolistic industry has significant barriers to entry. Though competitive firms can enter or leave industries in the long run, monopoly markets are considered nearly impossible to enter. Thus, monopolists face no competition, even in the long run.

market power A firm’s ability to set prices for goods and services in a market.

This gives pure monopolists what economists call market power. Unlike competitive firms, which are price takers, monopolists are price makers. Their market power allows monopolists to adjust their output in ways that give them significant control over product price.

As we noted already, nearly every firm has some market power, or some control over price. Your neighborhood dry cleaner, for instance, has some control over price because it is located close to you, and you are probably not going to want to drive 5 miles just to save a few cents. This control over price reaches its maximum in the case of monopolies, and becomes minor as markets approach more competitive conditions at the other end of the market structure spectrum.

Sources of Market Power

barriers to entry Any obstacle that makes it more difficult for a firm to enter an industry, and includes control of a key resource, prohibitive fixed costs, and government protection.

Monopoly is defined as one firm serving a market in which there are no close substitutes and entry is nearly impossible. Market power means that a firm has some control over price. As a market structure approaches monopoly, one firm gains the maximum market power possible for that industry. The key to the market power of monopolies is significant barriers to entry. These barriers can be of several forms.

Control Over a Significant Factor of Production If a firm owns or has control over an important input into the production process, that firm can keep potential rivals out of the market. This was the case with Alcoa Aluminum 75 years ago. Alcoa owned nearly all the world’s bauxite ore, a key ingredient in aluminum production, before the company was eventually broken up by the government.

223

A contemporary example would be the National Football League (NFL), which has negotiated exclusive rights with colleges to draft top players (the most important input), along with exclusive rights with television networks and sponsors to broadcast games. Such control over key components of football entertainment makes entry into the industry very difficult.

economies of scale As the firm expands in size, average total cost declines.

Economies of Scale The economies of scale in an industry (when average total cost declines with increased production) give an existing firm a competitive advantage over potential entrants. By establishing economies of scale early, an existing firm has the ability to underprice new competitors, thereby discouraging their entry into the market. By doing so, a firm increases its market power.

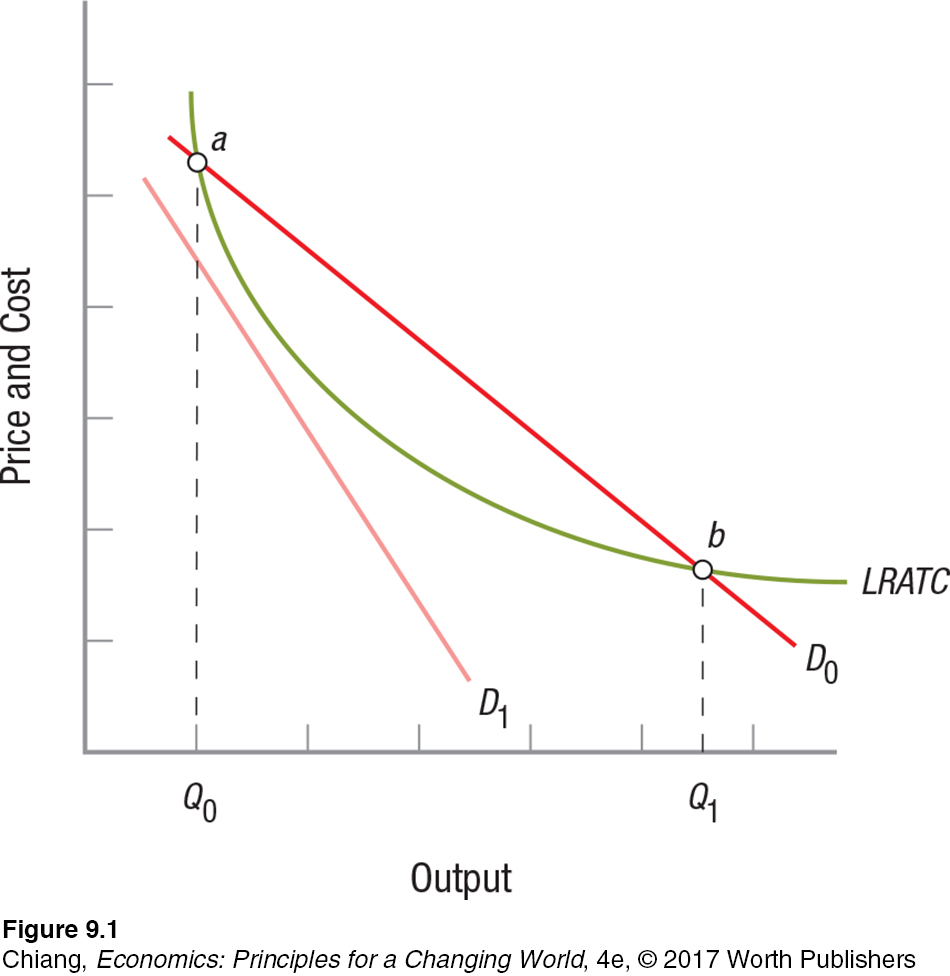

In some industries, economies of scale can be so large that demand supports only one firm. Figure 1 illustrates this case. Here the long-

Utility industries have traditionally been considered natural monopolists because of the high fixed costs associated with power plants and the inefficiency of several different electric companies stringing their wires throughout a city. Recent technology, however, is slowly changing the utilities industry, as smaller plants, solar units, and wind generators permit a smaller yet efficient scale of operation. Smaller plants can be quickly turned on and off, and the energy from the sun and wind is beginning to be stored and transported to where it is needed in the system.

Government Franchises, Patents, and Copyrights The government is the source of some barriers to market entry. A government franchise grants a firm permission to provide specific goods or services, while prohibiting others from doing so, thereby eliminating potential competition. The United States Postal Service, for example, has an exclusive franchise for the delivery of mail to your mailbox. Similarly, water companies typically are granted special franchises by state or local governments.

224

Patents provide legal protection to individuals who invent new products and processes, allowing the patent holder to reap the benefits from the creation for a limited period, usually 20 years. Patents are immensely important to many industries, including pharmaceuticals, technology, and automobile manufacturing. Many firms in these industries spend huge sums of money each year on research and development—

Some firms guard trade secrets to protect their assets for even longer periods than the limited timeframes provided by patents and copyrights. Only a handful of the top executives at Coca-

Monopoly Pricing and Output Decisions

Monopolies gain market power because of their barriers to entry. Shortly we will discuss some ways in which this power is maintained. First, however, let us consider the basics of monopoly pricing and output decisions. In the previous chapter, we saw that competitive firms maximize profits by producing at a level of output where MR = MC, selling this output at the established market price. The monopolist, however, is the market. It has the ability to set the price by adjusting output.

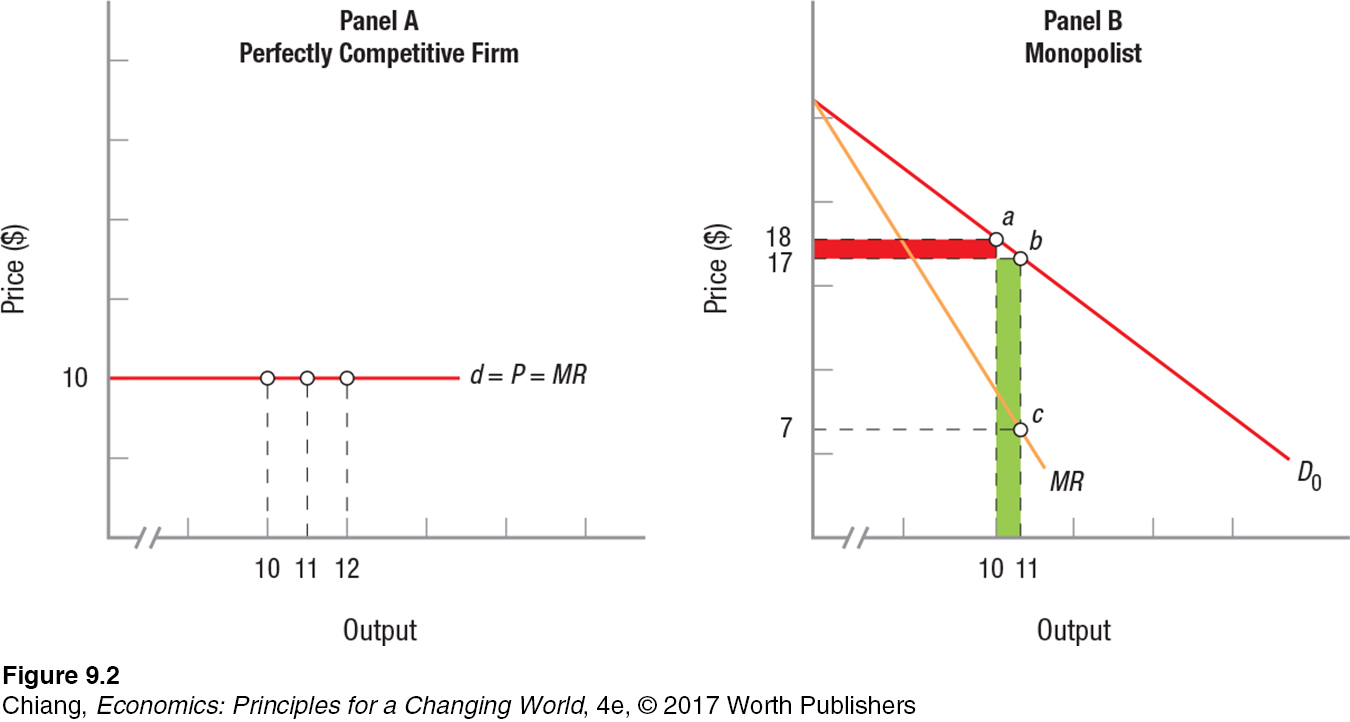

MR < P for Monopoly A monopolist faces a demand curve, just like a perfectly competitive firm. But there is a big difference. For the monopolist, marginal revenue is less than price (MR < P). To see why, look at Figure 2. Panel A shows the demand curve for a perfectly competitive firm. At a price of $10, the competitive firm can sell all it wants. For each unit sold, total revenue rises by $10. Recalling that marginal revenue is equal to the change in total revenue from selling an added unit of the product, marginal revenue is also $10.

225

Contrast this with the situation of the monopolist in panel B. Because the monopolist constitutes the entire industry, it faces the downward-

Notice that we are assuming the monopolist cannot sell the 10th unit for $18 and then sell the 11th unit for $17; rather, the monopolist must offer to sell a given quantity to the market at a single price per unit. We are assuming, in other words, that there is no way for the monopolist to separate the market by specific individuals who are willing to pay different prices for the product. Later in this chapter, we will relax this assumption and discuss price discrimination.

In summary, we can see from panel B of Figure 2 that MR < P, and the marginal revenue curve is always plotted below the demand curve for the monopolist. This contrasts with the situation of the perfectly competitive firm, for which price and marginal revenue are always the same. We should also note that marginal revenue can be negative. In such an instance, total revenue falls as the monopolist tries to sell more output. However, no profit-

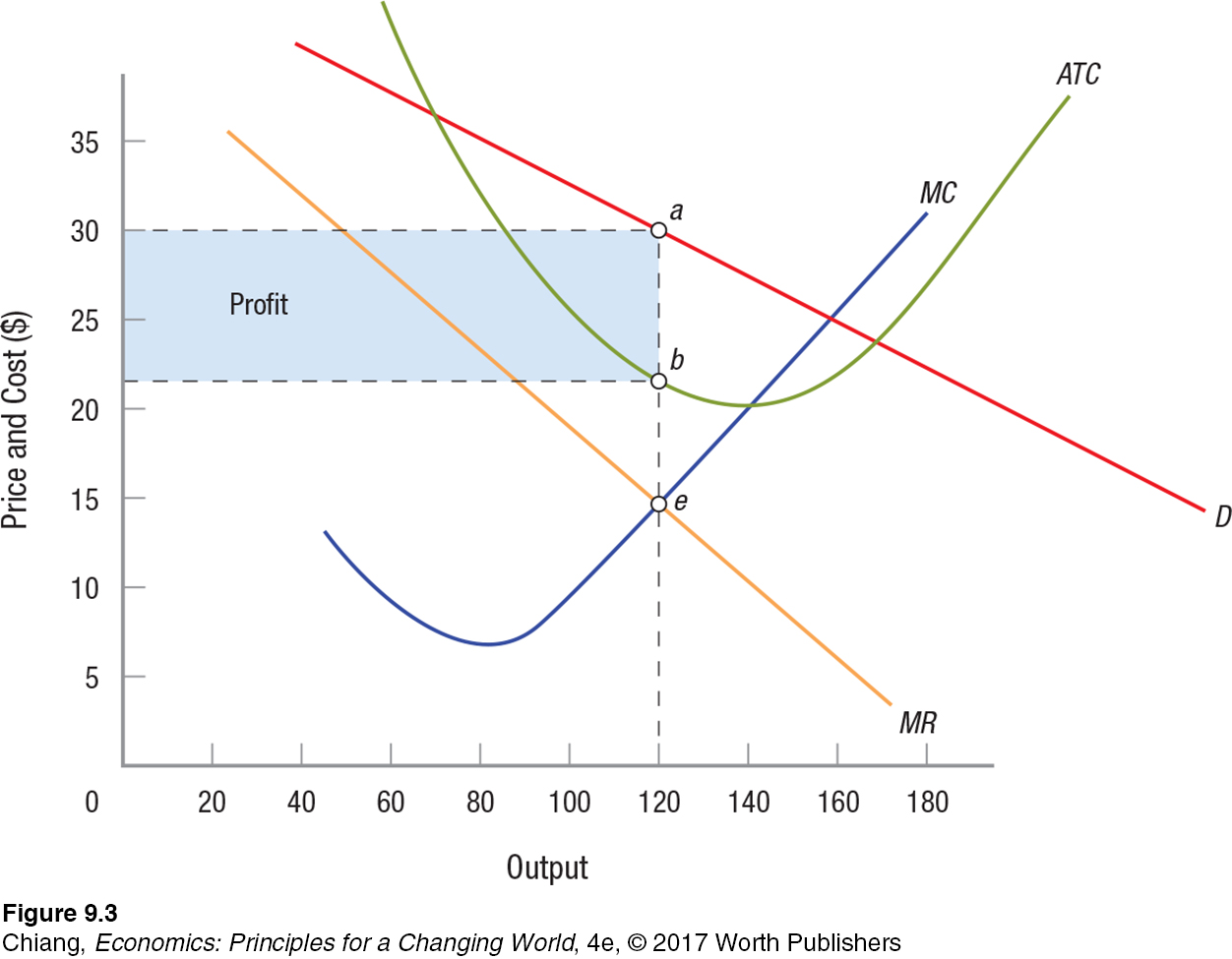

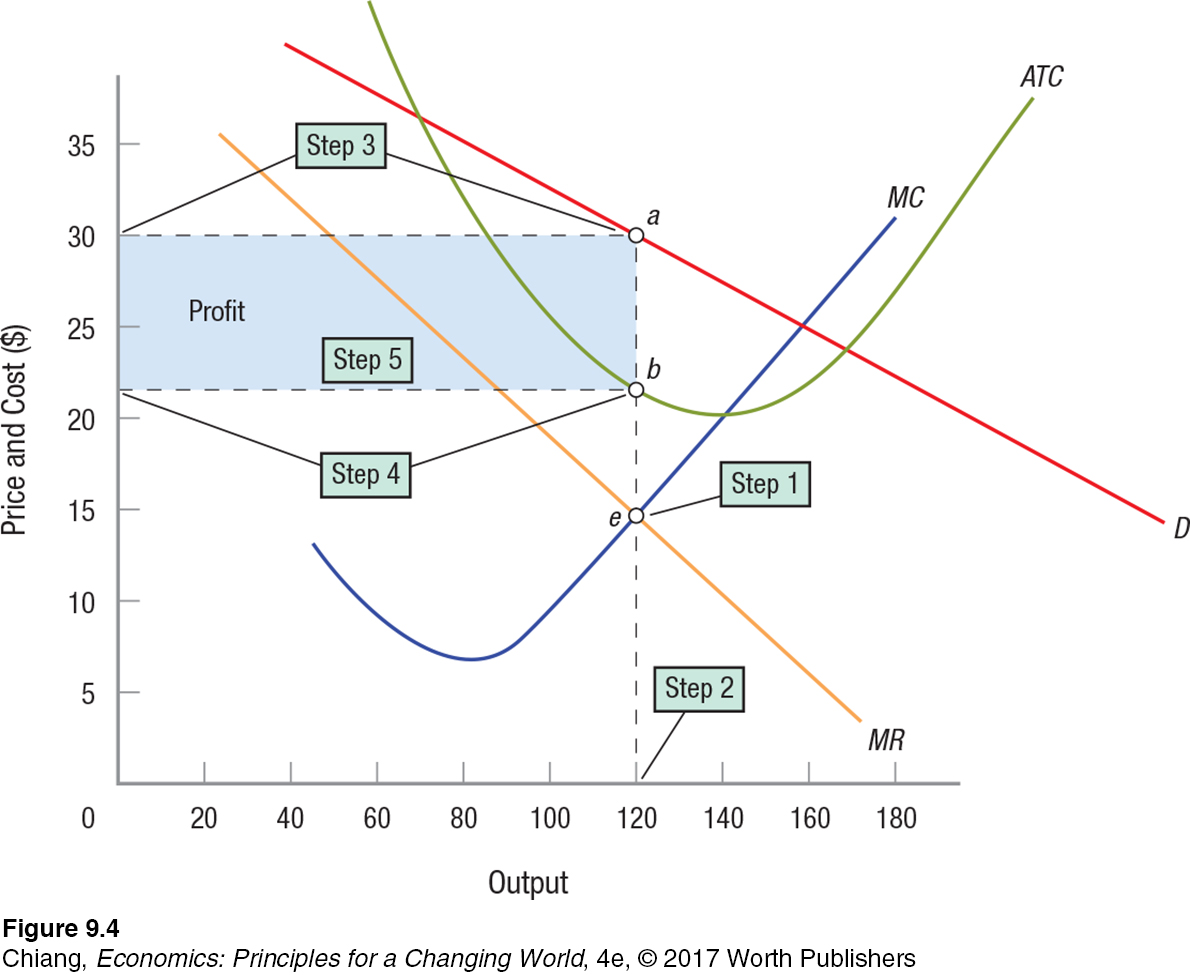

Equilibrium Price and Output As noted earlier, product price is determined in a monopoly by how much the monopolist wishes to produce. This contrasts with the perfectly competitive firm that can sell all it wishes, but only at the market-

Like competitive firms, the profit-

226

Profit for each unit is equal to $8, the difference between price ($30) and average total cost ($22). Profit per unit times output equals total profit ($8 × 120 = $960), as indicated by the shaded area in Figure 3. Following the MR = MC rule, profits are maximized by selling 120 units of the product at $30 each.

Using the Five Steps to Maximizing Profit We can use the same five-

Step 1: Find the point at which MR = MC.

Step 2: At that point, look down and determine the profit-

Step 3: At this output, extend a vertical line upward to the demand curve and follow it to the left to determine the equilibrium price on the vertical axis.

226

227

Step 4: Using the same vertical line, find the point on the ATC curve to determine the average total cost per unit on the vertical axis.

Step 5: Find total profit by taking P − ATC, and multiply by output.

Using the five-

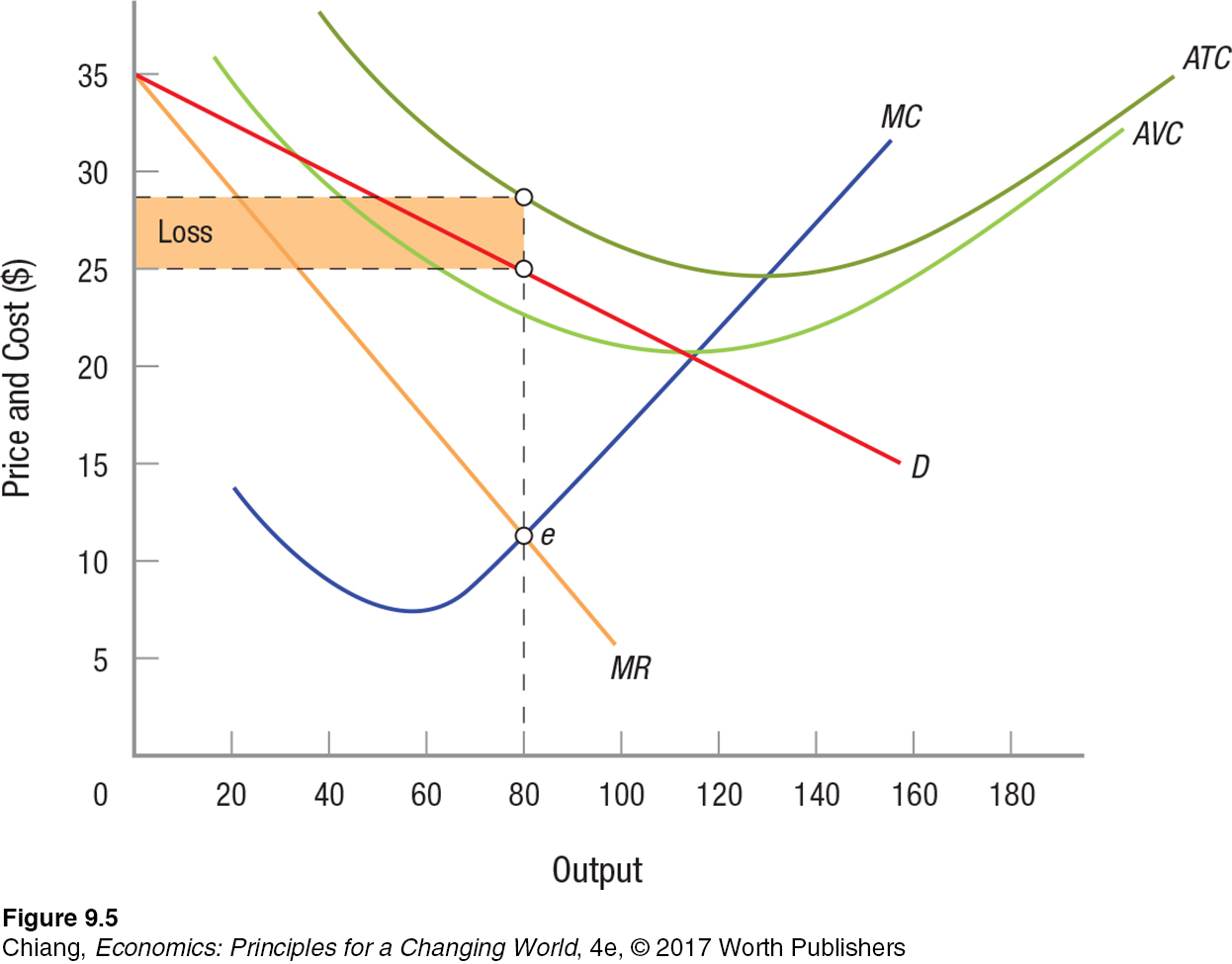

Monopoly Does Not Guarantee Economic Profits We have seen that competitive firms may or may not be profitable in the short run, but in the long run, they must earn at least normal profits to remain in business. Is the same true for monopolists? Yes. Consider the monopolist in Figure 5. This firm maximizes profits by producing where MR = MC (point e) and selling 80 units of output for a price of $25.

In this case, however, price ($25) is lower than average total cost ($28), and thus the monopolist suffers the loss of $240 (−$3 × 80 = −$240) indicated by the shaded area. Because price nonetheless exceeds average variable costs, the monopolist will minimize its losses in the short run by continuing to produce. But if price should fall below AVC, the monopolist, just like any competitive firm, will minimize its losses at its fixed costs by shutting down its plant. If these losses persist, the monopolist will exit the industry in the long run.

This is an important point to remember. Being a monopolist does not automatically mean that there will be monopoly profits to haul in. Even monopolies face some cost and price pressures, and they face a demand curve, which ultimately limits their price making.

ISSUE

“But Wait … There’s More!” The Success and Failure of Infomercials

“But wait … there’s more!” is a familiar phrase to anyone who has watched an infomercial selling unique products that generally are not sold in retail stores. The size of the infomercial industry is significant and growing. In 2015 infomercials generated about $250 billion in sales. What do infomercials sell? Why are they successful and why do many infomercial products fail?

Unlike regular television commercials, which air for 30 seconds or 1 minute during daytime and primetime shows, infomercials typically are longer, ranging from 1 minute to 30 minutes or longer. The longest infomercials typically air in the middle of the night when television advertising rates are much lower.

Infomercials typically sell newly invented products that are not well known. Most infomercial products fit the monopoly market structure because although the product may have similarities to other products, infomercials advertise them as one-

Infomercials focus on the product characteristics that make the product completely different from anything on the market. Because the target market of infomercials is consumers who buy on impulse, even in the middle of the night, they use various techniques to increase sales. First, many infomercials show a high “retail” price (such as $100) and then reduce it rapidly until it becomes $19.99. Second, infomercials will offer something extra with the tag line “But wait … there’s more!” Third, many infomercials show a fixed time period in which to buy, often within hours, even if the deadline is not actually enforced. And last, infomercials tend to offer return policies and often lifetime warranties (which is attractive but not that valuable if the company fails).

Some infomercials have become remarkably successful, with the product even sold in stores. One example of a successful product that started from an infomercial is the Ped Egg, a cheese-

228

CHECKPOINT

MONOPOLY MARKETS

Monopoly is a market with no close substitutes, high barriers to entry, and one seller; the firm is the industry. Hence, monopolists are price makers.

Monopolies gain maximum market power from control over an important input, economies of scale, or from government franchises, patents, and copyrights.

For the monopolist, MR < P because the industry’s demand is the monopolist’s demand.

Profit is maximized by producing that output where MR = MC and setting the price from the demand curve.

Being a monopolist does not guarantee economic profits if demand is insufficient to cover costs.

QUESTIONS: When legendary country singer Dolly Parton goes on tour, sometimes she will perform in a relatively small (< 1,500 seats) venue when she could easily fill much larger arenas. Why would music artists intentionally choose a smaller venue? Wouldn’t they make more money if they performed in a larger arena?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

By performing in a smaller venue (such as a performing arts hall with 1,500 seats instead of an arena with 10,000 or more seats), the artist can target the core fans willing to pay high prices for tickets. With market power in pricing (there is only one Dolly Parton), nearly all seats would be sold at the high price, as opposed to having to offer much lower prices to fill a larger arena. If the costs of performing at a larger arena are significant, artists can do better by producing less (selling fewer tickets), charging a much higher price, and reducing the costs of putting on the concert.