WHY IS THE PUBLIC DEBT SO IMPORTANT?

We have seen that politicians have a bias toward using expansionary fiscal policy and not contractionary fiscal policy, and also have a bias toward using debt rather than taxes to finance the ensuing deficits. This explains the persistence of federal debt. We have seen that balancing the federal budget by passing an amendment is not an ideal solution. This leads to the following questions: How big a problem is persistent deficits? Should we be worrying about this now?

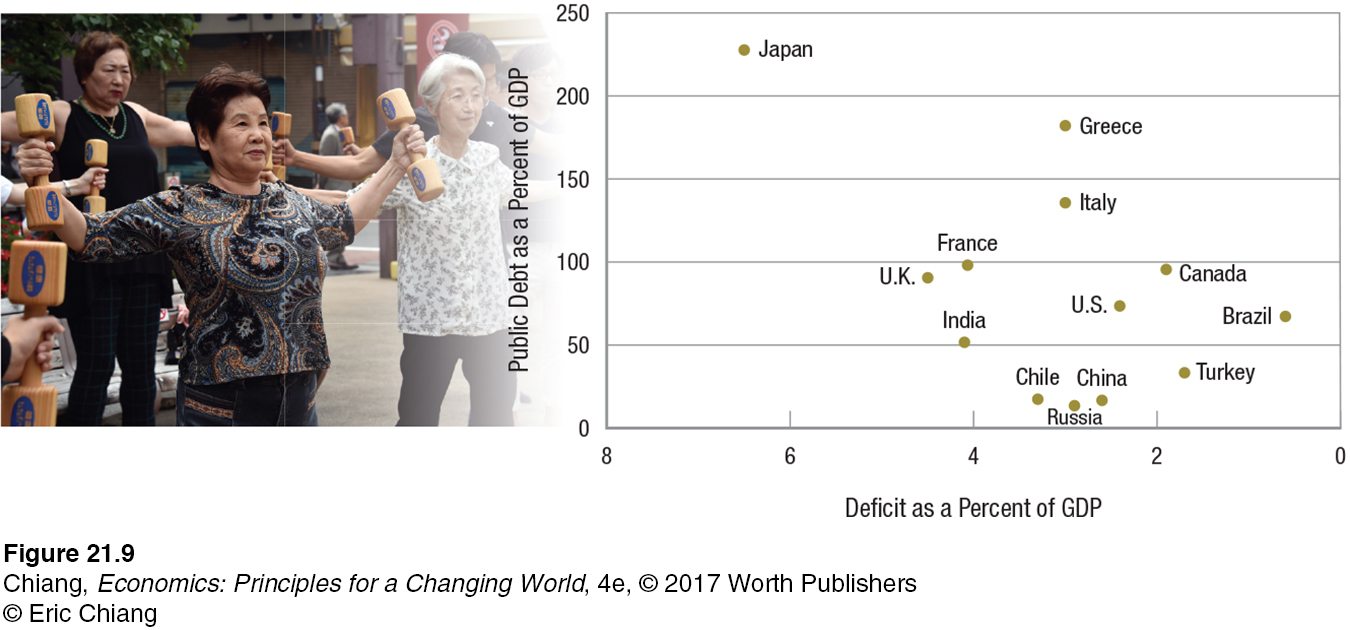

Figure 9 shows the debt of mostly developed nations in 2015. Japan, Greece, and Italy had a large debt relative to their GDP, but Greece and Italy have reduced their deficit in recent years, allowing the increase in debt to slow. India has a relatively low debt ratio but has seen higher deficits recently. China, Russia, and Chile have very low debt ratios, but deficits in all three countries have risen in recent years as economic growth slowed. When an economy moves toward the upper left portion of the figure, problems begin to rise. In Japan, an aging population (fact: Japan has more people over the age of 100 than any other country in the world!) along with a shrinking working-

Politicians frequently warn that the federal government is going bankrupt, or that we are burdening future generations with our own enormous public debt. After all, U.S. public debt of nearly $14 trillion means that every baby born in the United States begins life saddled with over $42,000 in public debt. Before you start panicking, let’s examine the burden of the public debt.

Is the Size of the Public Debt a Problem?

Public debt in the United States represents a little over 70% of GDP. Is this amount of debt a cause for immediate concern? It really depends on the costs of financing the debt. What is the burden of the interest rate payments on the debt?

Think about it another way. Suppose that you earn $50,000 a year and have $35,000 in student loan debt, equal to 70% of your annual income. Is this a problem? It would be if the interest rate on the student loans were 20% a year, because interest payments of $7,000 per year would take up a significant chunk (14%) of your gross salary. But if the interest rate is 3%, the debt burden from the interest ($1,050 per year) would not be as substantial, representing only about 2% of your gross salary.

For the U.S. national debt, current interest rates are relatively low due in large part to aggressive action by the Federal Reserve. Interest costs on the national debt were $223 billion in 2015, representing about 6% of the federal budget. That is not an overwhelming amount.

Wouldn’t it be wise to pay the debt down or pay it off? Not necessarily. Many people today “own” some small part of the public debt in their pension plans, but many others do not. If taxes were raised across the board to pay down the debt, those who did not own any public debt would be in a worse position than those who did.

Servicing the debt requires taxing the general public to pay interest to bondholders. Most people who own part of the national debt (or who indirectly own parts of entities that hold the debt) tend to be richer than those who do not. This means that money is taken from those across the income or wealth distribution and given to those near the top. Still, the fact that taxes are mildly progressive mitigates some, and perhaps even all, of this reverse redistribution problem.

Thus, the public debt is not out of control, at least based on the economy’s ability to pay the interest costs. However, rising interest rates will raise the burden of this debt. Even so, at its current size, the public debt is manageable as long as it does not experience another spike in the near term.

Another consideration is whether the debt is mostly held externally (i.e., financed by foreign governments, banks, and investors), as is the case of many developing countries. These countries have discovered that relying on foreign sources of financing has its limits.

Does It Matter If Foreigners Hold a Significant Portion of the Public Debt?

The great advantage of citizens being creditors as well as debtors with relation to the public debt is obvious. Men readily perceive that they can not be much oppressed by a debt which they owe to themselves.

—ABRAHAM LINCOLN (1864)

internally held debt Public debt owned by domestic banks, corporations, mutual funds, pension plans, and individuals.

externally held debt Public debt held by foreigners, including foreign industries, banks, and governments.

Consider first, as Abraham Lincoln noted in 1864, that much of the national debt held by the public is owned by American banks, corporations, mutual funds, pension plans, and individuals. As a people, we essentially own this debt—

| TABLE 1 | DISTRIBUTION OF NATIONAL DEBT, AS OF MARCH 2016 (TRILLIONS) | |||||

| Amount | Percent | |||||

| Held by the Federal Reserve and government agencies | $5.316 | 27.7% | ||||

| Held by the public | 13.872 | 72.3 | ||||

| Held by foreigners | 6.435 | 33.5 | ||||

| Held domestically | 7.437 | 38.8 | ||||

| Total national debt | 19.188 | 100.00 | ||||

Data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Of the interest paid on the $19.2 trillion national debt, about 28% goes to federal agencies holding this debt—

The interest paid on externally held debt represents a real claim on our goods and services, and thus can be a real burden on our economy. Debt held by the public has grown, and the portion of the debt held by foreigners has expanded. Until the mid-

Traditionally much of the U.S. debt is held internally, but this is changing. In just a decade, foreign holdings have doubled to nearly 50% of debt held by the public, and about 40% of this is held by China and Japan. Why such a rapid expansion of foreign holdings since the 1990s? One reason is that these countries are buying our debt to keep their currencies from rising relative to the dollar. When their currencies rise, their exports to America are more costly; as a result, sales fall, hurting their economies. It is better to accumulate U.S. debt than see their export sectors suffer.

However, the increased reliance on external financing of our debt raises some concerns. For example, the significant amount of our debt held by China makes our economy more vulnerable to policy changes by the Chinese government and/or businesses that hold our debt. On the positive side, however, creditors such as China are likely to maintain strong economic and political ties with the United States; besides, China eventually will want its money back.

Does Government Debt Crowd Out Consumption and Investment?

As we saw in the budget constraint section earlier, when the government runs a deficit, it must sell bonds to either the public or the Federal Reserve. If it sells bonds to the Federal Reserve (prints money) when the economy is near full employment, the money supply will grow and inflation will result.

crowding-

Alternatively, when the federal government spends more than tax revenues permit, it can sell bonds to the public. But doing so drives up interest rates as the demand for loanable funds (this time by the government rather than the public sector) increases. As interest rates rise, consumer spending on durable goods such as cars and appliances, often bought on credit, falls. It also reduces private business investment. Therefore, while deficit spending is usually expansionary, the consequence is that future generations will be bequeathed a smaller and potentially less productive economy, resulting in a lower standard of living. This is the crowding-

The crowding-

How Will the National Debt Affect Our Future? Are We Doomed?

fiscal sustainability A measure of the present value of all projected future revenues compared to the present value of projected future spending.

If the federal debt is not an enormous burden now, what about in the future? Here there is a large cause for concern. Economists have argued that economic growth depends on the fiscal sustainability of the federal budget. For a fiscal policy to be fiscally sustainable, the present value (current dollar value) of all projected future revenues must be equal to the present value of projected future spending. If the budget is not fiscally sustainable, an intergenerational tax burden may be created, with future generations paying for the spending of the current generation.

Clearly, some tax burden shifting is sensible. When current fiscal policy truly invests in the economy, future generations benefit, and therefore, some of the present costs may justifiably be shifted to them. Investments in infrastructure, education, research, national defense, and homeland security are good examples.

However, the federal government has immense obligations that extend over long periods that are unrelated to economic investment. Its two largest programs, Social Security and Medicare, account for over 35% of all federal spending. People who are just beginning to enter retirement can expect to live for two or three more decades. Add to this the fact that medical costs are growing at rates significantly higher than economic growth as new and more sophisticated treatments are developed and demanded.

The intergenerational impact results from the fact that Social Security and Medicare are pay-

With the current national debt held by the public at nearly $14 trillion, and total future liabilities (the money that has been promised, such as for Social Security and Medicare, but have not been paid) estimated to be several times the current public debt, the implications for future budgeting are significant. In other words, without some significant change in economic or demographic growth, taxes will have to be increased dramatically at some point, or else the benefits for Social Security and Medicare will have to be drastically cut.

If these estimates of fiscal imbalance are on track, fiscal policy is headed for a train wreck as the baby boomers keep retiring. The public choice analysis discussed earlier suggests that politicians will try to keep this issue off the agenda for as long as possible, one side fighting tax increases while the other resists benefit reductions. Clearly, given the magnitudes discussed here, this problem will be difficult to solve.

We started this chapter by talking about the government’s ability to address fluctuations in the business cycle by using fiscal policy to affect aggregate demand and aggregate supply. But given the government’s penchant for expansionary policy, persistent budget deficits tend to result. Unlike for individuals, the federal government has the ability to incur debt for some time because of its ability to print money and borrow from the public. And while the federal government is currently able to safely manage its debt, this picture may change down the road as Social Security and Medicare liabilities continue to grow. The implication is that we are better off dealing with this future problem now rather than later.

CHECKPOINT

WHY IS THE PUBLIC DEBT SO IMPORTANT?

Interest payments on the debt exceed 6% of the federal budget. These funds could have been spent on other programs.

About half of the public debt held by the public is held by domestic individuals and institutions, and half is held by foreigners. The domestic half is internally held and represents transfers among individuals, but that part held by foreigners is a real claim on our resources.

When the government pays for the deficit by selling bonds, interest rates rise, crowding out some consumption and private investment and reducing economic growth. To the extent that these funds are used for public investment and not current consumption, this effect is mitigated.

The rising costs of Social Security and Medicare represent the biggest threat to the long-

run federal budget. Either the costs of such programs eventually need to be reduced, or additional taxes will be required to cover these rising expenses.

QUESTIONS: Suppose China and Japan, the two largest external creditors of U.S. public debt, choose to diversify their asset holdings by selling some of their U.S. Treasury bonds. How will this affect the U.S. government’s ability to finance its debt? What might happen to consumption and investment in the United States?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

If China and Japan reduce their holdings of U.S. debt, interest rates would need to rise in order to attract other investors to purchase these bonds. Rising interest rates would adversely affect consumption and investment in the United States, potentially slowing economic growth.