THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

The previous section discussed how savers and borrowers interact in a market such that those who demand money for various reasons are able to turn to those who have extra money to save. The interest rate is what keeps this market in equilibrium between savers and borrowers. But how does one actually go about saving or borrowing money?

Suppose you have an extra $1,000 that you want to save for the future, and a buddy from your old high school asks you to invest in a new skateboard shop he plans to open on campus. Do you lend your money to him?

That should depend on a number of factors. First, will your friend be paying you interest or a share of his profits? Second, how risky would such an investment be? Is your friend borrowing from you because he can’t qualify for a small business loan elsewhere? Third, when will you expect to get your money back? Next year, or just whenever the business makes enough profit to pay you back? Or perhaps never if the shop goes bust.

These are important questions to evaluate before making financial decisions about your money. Often, the time it takes to evaluate proposals such as lending money to your buddy and to everyone else you know looking to borrow money can be significant and costly. For this reason, many individuals instead choose to save by putting money into banks, bonds, and stocks, which together represent the financial system.

The Bridge Between Savers and Borrowers

financial system A complex set of institutions, including banks, bond markets, and stock markets, that allocate scarce resources (financial capital) from savers to borrowers.

financial intermediaries Financial firms (banks, mutual funds, insurance companies, etc.) that acquire funds from savers and then lend these funds to borrowers (consumers, firms, and governments).

The financial system is a complex set of institutions that, in the broadest sense, allocates scarce resources (financial capital) from savers, those who are spending less than they earn, to borrowers, those who want to use these resources to invest in potentially profitable projects. Both savers and borrowers can include households, firms, and governments, but our focus is on households as savers and firms as borrowers. As we have seen, savers expect to earn interest on their savings and borrowers expect to pay interest on what they borrow. Households may save for a down payment on a house or a new car, and firms borrow to invest in new plants, equipment, or research and development.

Financial institutions or financial intermediaries are the bridge between savers and borrowers. They include, among others, commercial banks, savings and loan associations, credit unions, insurance companies, securities firms (brokerages), and pension funds. The complexity of a country’s financial institutions often is a sign of economic efficiency and growth, as these financial firms take savings from savers and loan them to borrowers.

The Roles of Financial Institutions

Financial institutions fulfill three important roles that facilitate the flow of funds to the economy. They (1) reduce information costs, (2) reduce transaction costs, and (3) spread risk by diversifying assets.

Reducing Information Costs Information costs are the expenses associated with gathering information on individual borrowers and evaluating their creditworthiness. Savers (in this case, lenders) would have a difficult time without financial institutions. For example, when deciding whether to lend your buddy money to open his skateboard shop, you might know plenty about your friend’s personality and habits, but have few ways to determine if his shop was safe to lend to or was unsound, or even just a fraud. Financial institutions reduce information costs by screening, evaluating, and monitoring firms to see that they are creditworthy and use the borrowed funds loaned in a prudent manner.

Reducing Transaction Costs Transaction costs are those associated with finding, selecting, and negotiating contracts between individual savers and borrowers. Suppose your buddy needs much more than $1,000, and asks all of his friends to lend him money. Trying to set up contracts individually between many lenders and a borrower can be time-

Diversifying Assets to Reduce Risk Firms need funds for long-

The role of financial institutions in channeling funds from savers to investors is essential, because the people who save are often not the same people with profitable investment opportunities. Without financial institutions, investment would be a pale version of what we see today, and the economy would be a fraction of its size.

Types of Financial Assets

return on investment The earnings, such as interest or capital gains, that a saver receives for making funds available to others. It is calculated as earnings divided by the amount invested.

Savers have many options when it comes to where to put their money. The primary difference among the many types of financial assets available is the return on investment (ROI) one can achieve. A return on investment can be determined by the interest rate earned on savings accounts or CDs, or the capital gains, dividends, and other interest earned from investing in stocks or bonds. The ROI of an asset largely depends on the risk of the asset, with lower risk assets generally earning a lower ROI and higher risk assets earning a higher ROI.

The simplest way to save is to deposit money into a checking or savings account at your local bank. This is also the lowest risk approach to saving, because all savings up to $250,000 per account are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as long as the bank is a member. In its 85-

The advantages of placing savings in banks are clear—

Thus, in order to increase earnings on savings, savers must either (1) choose financial assets with lower liquidity, or (2) choose assets that carry a higher level of risk. One way to achieve this is to invest in bonds and stocks, to which we now turn our attention.

Savers can invest their funds directly in businesses by purchasing a bond or shares of stock from a firm using one of many brokerage firms easily accessible by ordinary individuals. Savers can also invest indirectly by providing funds to a financial institution (such as a bank or mutual fund) that channels those funds to borrowers. A share of stock represents partial ownership of a corporation, and its value is determined by the earning capacity of the firm. A bond, on the other hand, represents debt of the corporation. Bonds are typically sold in $1,000 denominations and pay a fixed amount of interest. If you own a bond, you are a creditor of the firm.

Bond Prices and Interest Rates

We examined real interest rates when we described the loanable funds market, and we described several direct and indirect financial instruments such as stocks, savings accounts, and bonds. But most of the loanable funds are in the form of corporate or government bonds. In 2016, the total value of loans made by U.S. commercial banks was almost $9 trillion, the total value of the U.S. bond market was about $41 trillion, and the total value of stocks traded in U.S. stock exchanges was about $25 trillion.

Because of the sheer size of the U.S. bond market, economists frequently look at financial markets from the viewpoint of the supply and demand for bonds. They often consider policy implications by their impact on the price of bonds and the quantity traded. It can be a little confusing because bond prices and interest rates are inversely related—

To see why bond prices and interest rates are inversely related, we need to analyze bond contracts more closely. A bond is a contract between a seller (the company or government issuing the bond) and a buyer that determines the following:

Coupon rate of the bond

Maturity date of the bond

Face value of the bond

The seller agrees to pay the buyer a fixed rate of interest (the coupon rate) on the face value of the bond (usually $1,000 for a corporate bond, but often much larger values for government bonds) until a future fixed date (the maturity date of the bond). For example, if XYZ Company issues a bond with a face value of $1,000 at a coupon rate of 5%, it agrees to pay the bondholder $50 per year until the maturity date of the bond. Note that this $50 payment per year is fixed for the life of the bond.

Once a bond is issued, it is subject to the forces of the marketplace. As economic circumstances change, people may be willing to pay more or less for a bond that originally sold for $1,000. The yield on a bond is the percentage return earned over the life of the bond. Yields change when bond prices change.

Assume, for instance, that when a $1,000 bond is issued, general interest rates are 5% so that the bond yields an annual interest payment of $50. For simplicity, let’s assume that the bond is a perpetuity bond—

Assume that market interest rates rise to 8%. Just how much would the typical investor now be willing to pay for this bond that returns $50 a year? We can approach this intuitively. If we can buy a $1,000 bond now that pays $80 per year, why would we pay $1,000 for a similar bond that pays only $50? Would we pay more or less for the bond that pays $50? If we can get a bond that pays $80 for $1,000, we would pay less for a bond paying $50.

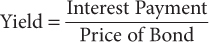

There is a simple formula we can use for perpetuity bonds:

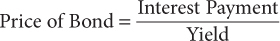

Or rearranging terms:

The new price of the bond will be $625 ($50 ÷ 0.08 = $625). Clearly, as market interest rates went up, the price of this bond fell. Conversely, if market interest rates were to fall, say, from 5% to 3%, the price of the bond would rise to $1,666.67 ($50 ÷ 0.03 = $1,666.67).

Keep this relationship between interest rates and bond prices in mind when we focus on the tools of monetary policy in the next couple of chapters, for this approach to bond pricing is important to understanding how the government manages the money supply through the purchase and sale of bonds.

Stocks and Investment Returns

An alternative to placing savings into banks or bonds is to purchase shares of stock (also known as equity) in a company. When one buys a share of stock, this share represents one fraction (of the total shares issued) of ownership in the company, and subsequently one vote at shareholder meetings and one share of any dividends (periodic payments to shareholders).

The buying and selling of stock shares occur in stock exchanges (such as the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ). The price of a share of stock is determined by supply and demand just as in any other market, and for every buyer of a share of stock there must be a seller.

Compared to bonds, stocks tend to be riskier investments, because shares, representing partial ownership as opposed to a creditor of a company, become worthless when a company goes bankrupt. Bonds are generally considered safer investments because bondholders are the first to be repaid when businesses face financial trouble. However, stockholders get to share in the company’s profits through dividend payments and the increase in share values, which can be substantial when a company succeeds. Both bonds and stocks are less liquid than savings and checking accounts, as both require the asset to be sold and a small commission paid in order to convert the asset into cash.

tradeoff between risk and return The pattern of higher risk assets offering higher average annual returns on investment than lower risk assets.

Which pays more over the long run, bonds or stocks? Given their higher risk, stocks tend to reward investors with a higher average return on investment over the long run, which follows the general rule of the tradeoff between risk and return. Riskier assets typically offer a greater return; otherwise, investors would not choose to take such risks. With the exception of a few periods during which the stock market dropped considerably (such as the crash in technology stocks from 2000 to 2001 and the stock market crash from late 2007 to early 2009 when many companies went bankrupt or nearly bankrupt), stocks generally trend upward, providing an average return on investment higher than what can be earned through less risky bonds and the least risky savings accounts and CDs, which are FDIC insured.

The complexity of the financial system offers savers and borrowers many opportunities to conduct economic transactions quickly and efficiently. But because the financial system also can be subject to corruption, financial institutions are heavily regulated to ensure the soundness and safety of the financial system and to increase the transparency and information to investors. The agencies regulating financial markets include the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Federal Reserve System, the FDIC, and another half-

Although heavily regulated, financial markets are complex environments that are occasionally subjected to meltdowns that can lead the economy into a recession and result in huge losses for the affected firms. When meltdowns occur, the bridge that financial intermediaries bring between savers and lenders can collapse.

CHECKPOINT

THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

Financial institutions are financial intermediaries that build a bridge between savers and borrowers.

Financial institutions reduce information costs, transaction costs, and risk, making financial markets more efficient.

Efficient financial markets foster growth because they maximize the amount of funds channeled from savers to borrowers.

Financial assets include savings and checking accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), bonds, stocks, and mutual funds.

Bond prices and interest rates are inversely related.

QUESTION: In 2008 voters in California approved the construction of a high-

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

The high-