PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

As we discovered in the previous section, all countries and all economies face constraints on their production capabilities. Production can be limited by the quantity of the various factors of production in the country and its current technology. Technology includes such considerations as the country’s infrastructure, its transportation and education systems, and the economic freedom it allows. Although perhaps going beyond the everyday meaning of the word “technology,” for simplicity, we will assume that all of these factors help determine the state of a country’s technology.

To further simplify matters, production possibilities analysis assumes that the quantity of resources available and the technology of the economy remain constant, and that the economy produces only two products. Although a two-

Production Possibilities

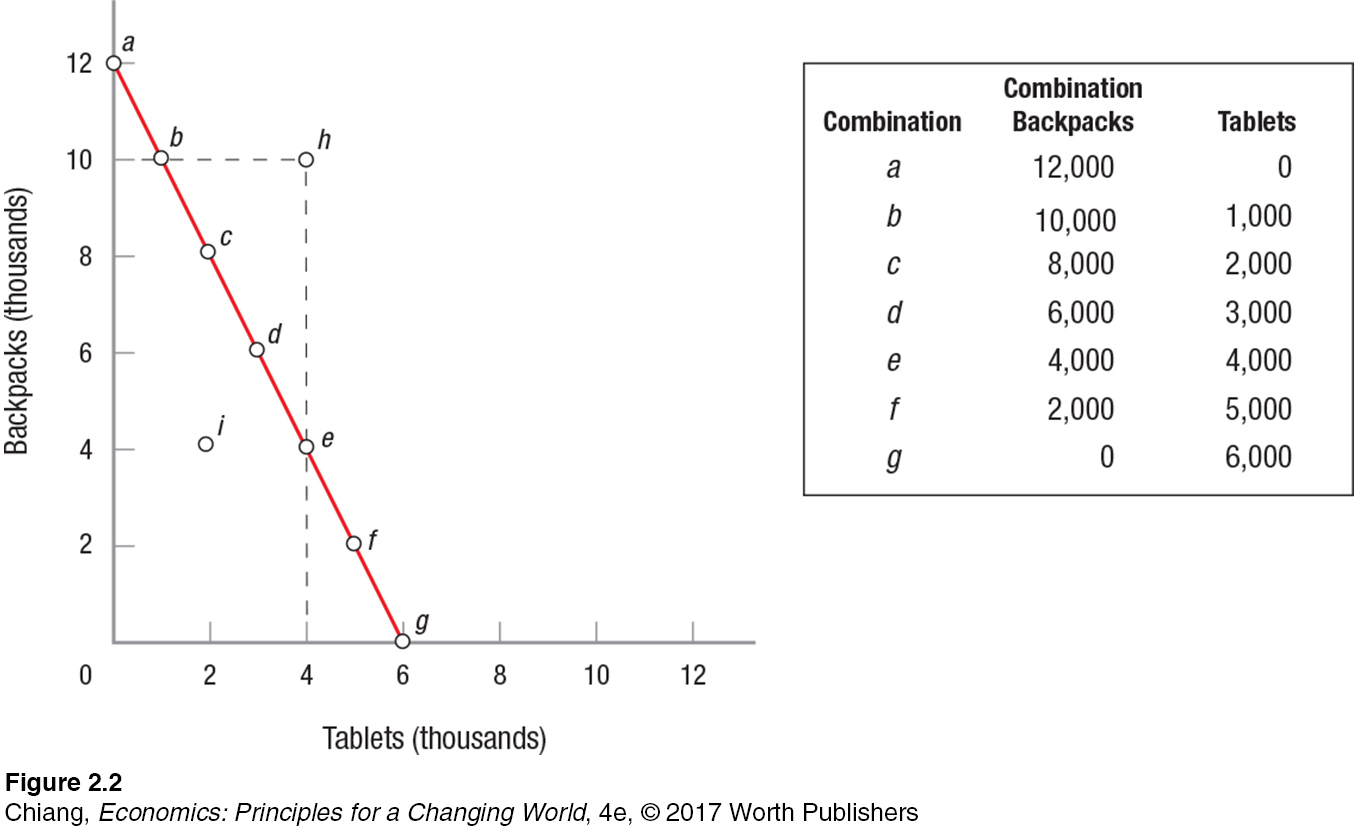

Assume that our simple economy produces backpacks and tablet computers. Figure 2 with its accompanying table shows the production possibilities frontier for this economy. The table shows seven possible production levels (a–

production possibilities frontier (PPF) Shows the combinations of two goods that are possible for a society to produce at full employment. Points on or inside the PPF are attainable, and those outside of the frontier are unattainable.

When we connect the seven production possibilities, we delineate the production possibilities frontier (PPF) for this economy (some economists refer to this curve as the production possibilities curve). All points on the PPF are considered attainable by our economy. Everything to the left of the PPF is also attainable, but is an inefficient use of resources—

What the PPF in Figure 2 shows is that, given an efficient use of limited resources and taking technology into account, this economy can produce any of the seven combinations of tablets and backpacks listed, each of which represents a combination where the economy cannot produce another unit without giving up something. If society wants to produce 1,000 tablets, it will only be able to produce 10,000 backpacks, as shown by point b on the PPF. Should the society decide that mobile Internet access is important, it might decide to produce 4,000 tablets, which would force it to cut backpack production to 4,000, shown by point e. At each of these points, resources are fully employed in the economy, and therefore increasing production of one good requires giving up some production of the other. Also, the economy can produce any combination of the two products on or within the PPF, but not any combination beyond it.

Contrast points c and e with production at point i. At point i, the economy is only producing 2,000 tablets and 4,000 backpacks. Clearly, some resources are not being used. When fully employed, the economy’s resources could produce more of both goods (point d).

Because the PPF represents combinations of goods using resources fully, the economy could not produce 4,000 tablets and still produce 10,000 backpacks. This situation, shown by point h, lies to the right of the PPF and hence outside the realm of possibility. Anything to the right of the PPF is impossible for our economy to attain.

opportunity cost The cost paid for one product in terms of the output (or consumption) of another product that must be forgone.

Opportunity Cost Whenever a country reallocates resources to change production patterns, it does so at a price. This price is called opportunity cost. Recall from Chapter 1 that opportunity cost is what you give up when making an economic decision. Here, society is deciding how many backpacks and tablets to produce. If society decides to produce more tablets, it gives up the ability to produce more backpacks. Shown through the PPF, the opportunity cost of producing more of one good is determined by the amount of the other good that is given up. In moving from point b to point e in Figure 2, tablet production increases by 3,000 units, from 1,000 units to 4,000 units. However, the country must forgo producing 6,000 backpacks because production falls from 10,000 backpacks to 4,000 backpacks. Giving up 6,000 backpacks for 3,000 more tablets represents an opportunity cost of 6,000 backpacks for these 3,000 tablets, or two backpacks for each tablet.

Opportunity cost thus represents the tradeoff required when an economy wants to increase its production of any single product. Governments must choose between infrastructure and national parks, or between military spending and social spending. Since there are limits to what taxpayers are willing to pay, spending choices are necessary. Think of opportunity costs as what you or the economy must give up to have more of a product or service.

Increasing Opportunity Costs In most cases, land, labor, and capital cannot easily be shifted from producing one good or service to another. You cannot take a semitrailer and use it to plow a field, even though the semi and a top-

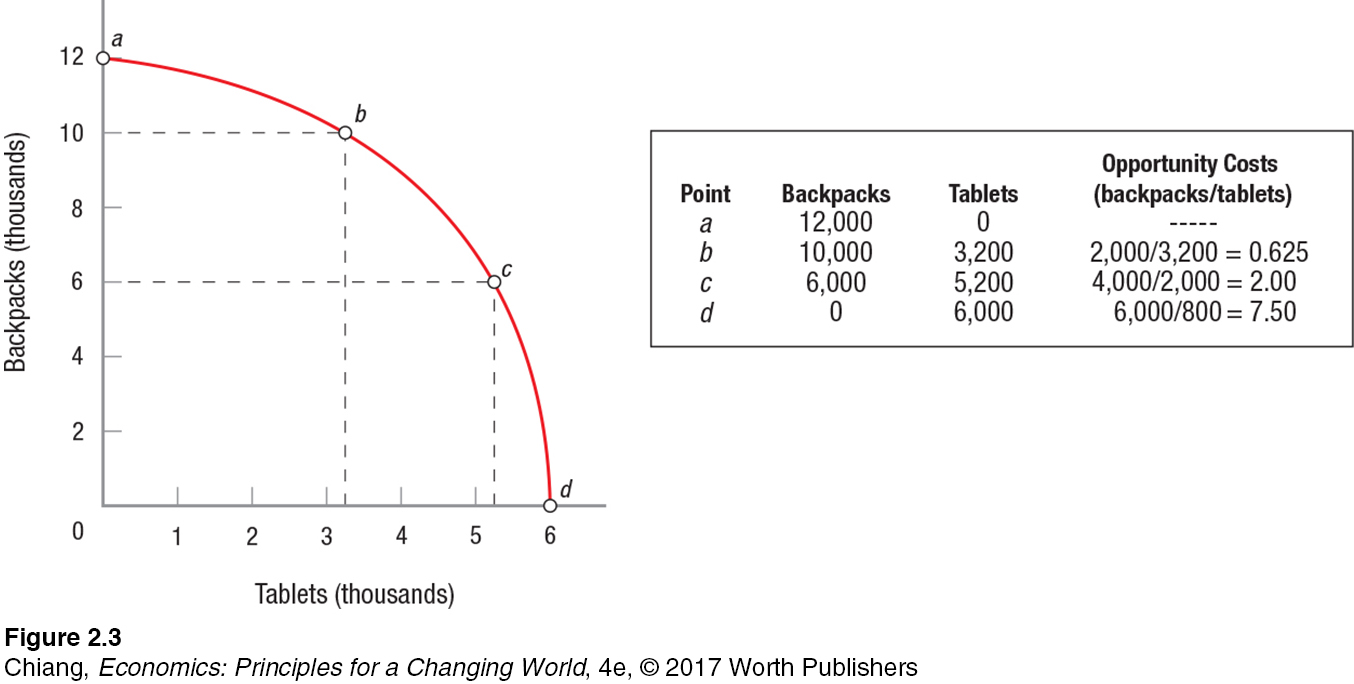

Thus, a more realistic production possibilities frontier is shown in Figure 3. This PPF is concave to (or bowed away from) the origin, because opportunity costs rise as more factors are used to produce increasing quantities of one product. Another way of saying this is that resources are subject to diminishing returns as more resources are devoted to the production of one product. Let’s consider why this is so.

Let’s begin at a point at which the economy’s resources are strictly devoted to backpack production (point a). Now assume that society decides to produce 3,200 tablets. This will require a move from point a to point b. As we can see, 2,000 backpacks must be given up to obtain the added 3,200 tablets. This means the opportunity cost of 1 tablet is 0.625 backpacks (2,000 ÷ 3,200 = 0.625). This is a low opportunity cost, because those resources that are better suited to producing tablets will be the first ones shifted into this industry.

But what happens when this society decides to produce an additional 2,000 tablets, or moves from point b to point c on the graph? As Figure 3 illustrates, each additional tablet costs 2 backpacks because producing 2,000 more tablets requires the society to sacrifice 4,000 backpacks. Thus, the opportunity cost of tablets has more than tripled due to diminishing returns on the tablet side, which arise because added resources are not as well suited to the production of tablets.

To describe what has happened in plain terms, when the economy was producing 12,000 backpacks, all its resources went into backpack production. Those members of the labor force who are engineers and electronic assemblers were probably not well suited to producing backpacks. As the economy reduces backpack production to start producing tablets, the opportunity cost of tablets was low, because the resources first shifted, including workers, were likely to be the ones most suited to tablet production and least suited to backpackmanufacture. Eventually, however, as tablets became the dominant product, manufacturing more tablets required shifting workers skilled in backpack production to the tablet industry. Employing these less suitable resources drives up the opportunity costs of tablets.

You may be wondering which point along the PPF is the best for society. Economists have no grounds for stating unequivocally which mixture of goods and services would be ideal. The perfect mixture of goods depends on the tastes and preferences of the members of society. In a capitalist economy, resource allocation is determined largely by individual choices and the workings of private markets. We consider these markets and their operations in the next chapter.

Economic Growth

We have seen that PPFs map out the maximum that an economy can produce: Points to the right of the PPF are unattainable. But what if the PPF can be shifted to the right? This shift would give economies new maximum frontiers. In fact, we will see that economic growth can be viewed as a shift in the PPF outward. In this section, we use the production possibilities model to determine some of the major reasons for economic growth. Understanding these reasons for growth will enable us to suggest some broad economic policies that could lead to expanded growth.

The production possibilities model holds resources and technology constant to derive the PPF. These assumptions suggest that economic growth has two basic determinants: expanding resources and improving technologies. The expansion of resources allows producers to increase production of all goods and services in an economy. Specific technological improvements, however, often affect only one industry directly. The development of a new color printing process, for instance, will directly affect only the printing industry.

Nevertheless, ripples from technological improvements can spread out through an entire economy, just like ripples in a pond. Specifically, improvements in technology can lead to new products, improved goods and services, and increased productivity.

Sometimes technological improvements in one industry allow other industries to increase their production with existing resources. This means producers can increase output without using added labor or other resources. Alternatively, they can get the same production levels as before by using fewer resources than before. This frees up resources in the economy for use in other industries.

When the electric lightbulb was invented, it not only created a new industry (someone had to produce lightbulbs), but it also revolutionized other industries. Factories could stay open longer since they no longer had to rely on the sun for light. Workers could see better, thus improving the quality of their work. The result was that resources operated more efficiently throughout the entire economy.

The modern-

Expanding Resources The PPF represents the possible output of an economy at a specific time. But economies are constantly changing, and so are PPFs. Capital and labor are the principal resources that can be changed through government action. Land and entrepreneurial talent are important factors of production, but neither is easy to change by government policies. The government can make owning a business easier or more profitable by reducing regulations, or by offering low-

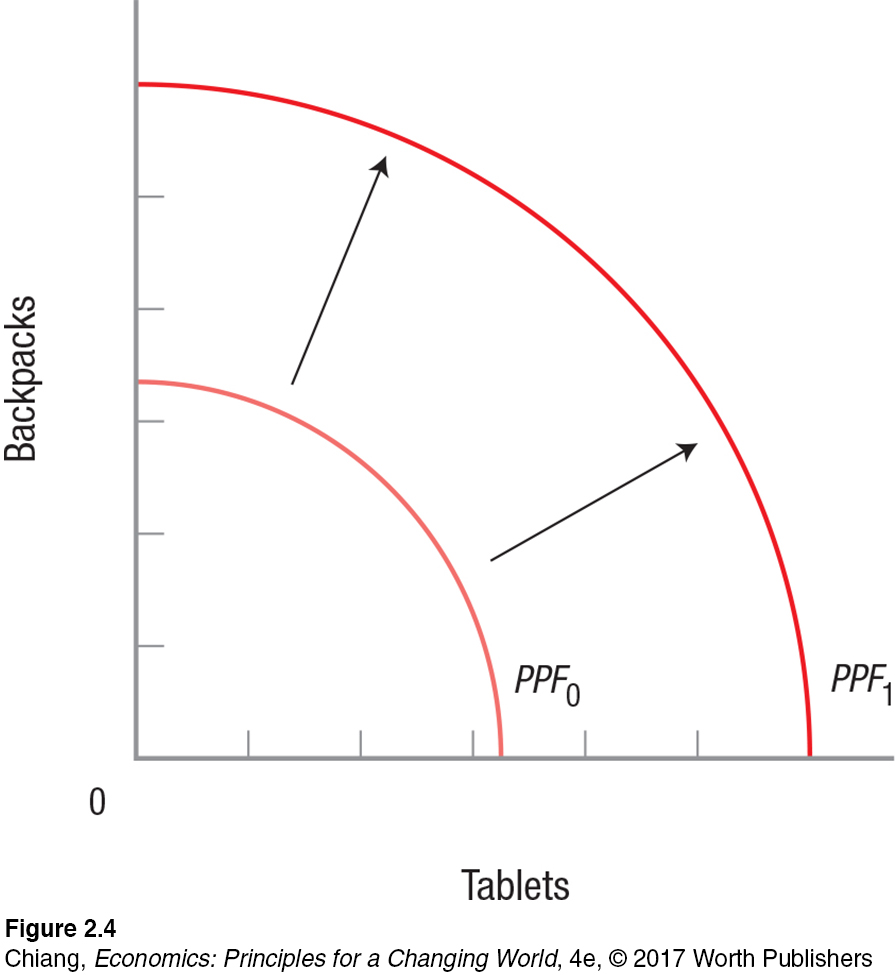

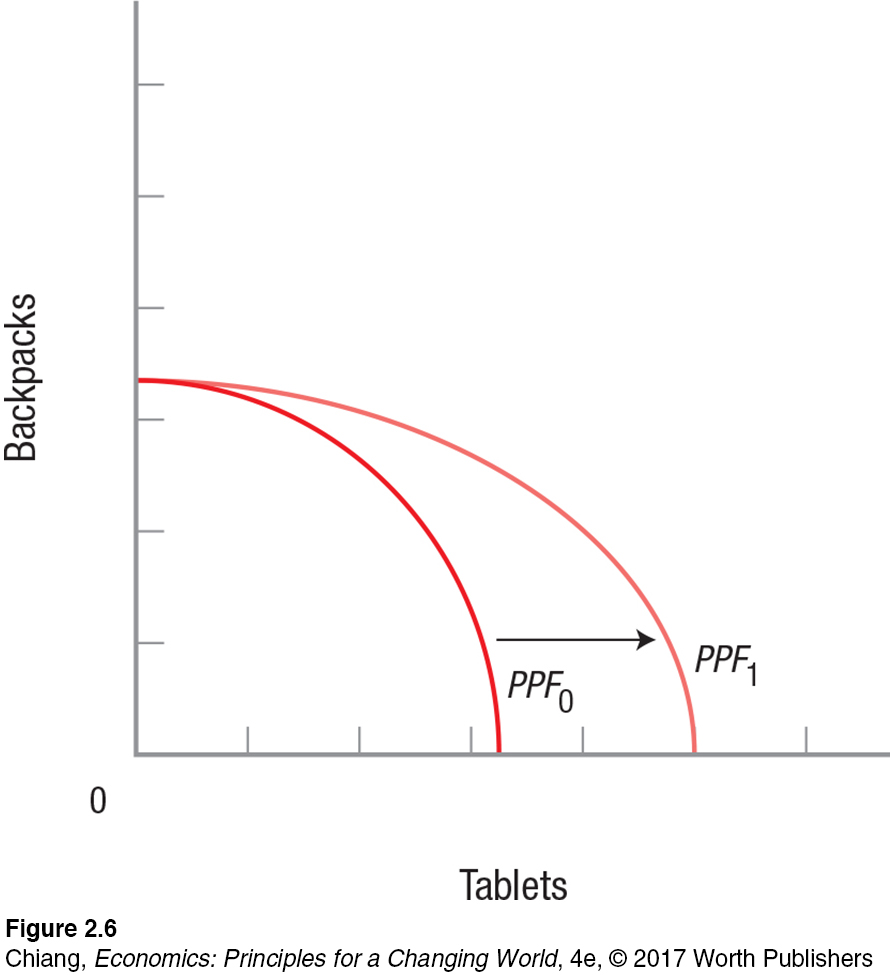

Increasing Labor and Human Capital A clear increase in population, the number of households, or the size of the labor force shifts the PPF outward, as shown in Figure 4. With added labor, the production possibilities available to the economy expand from PPF0 to PPF1. Such a labor increase can be caused by higher birthrates, increased immigration, or an increased willingness of people to enter the labor force. This last type of increase has occurred over the past several decades as more women have entered the labor force on a permanent basis. America’s high level of immigration (both legal and illegal) fuels a strong rate of economic growth.

Rather than simply increasing the number of people working, however, the labor factor can also be increased by improving workers’ skills. Economists refer to this as investment in human capital. Education, on-

Capital Accumulation Increasing the capital used throughout the economy, usually brought about by investment, similarly shifts the PPF outward, as shown in Figure 4. Additional capital makes each unit of labor more productive and thus results in higher possible production throughout the economy. Adding robotics and computer-

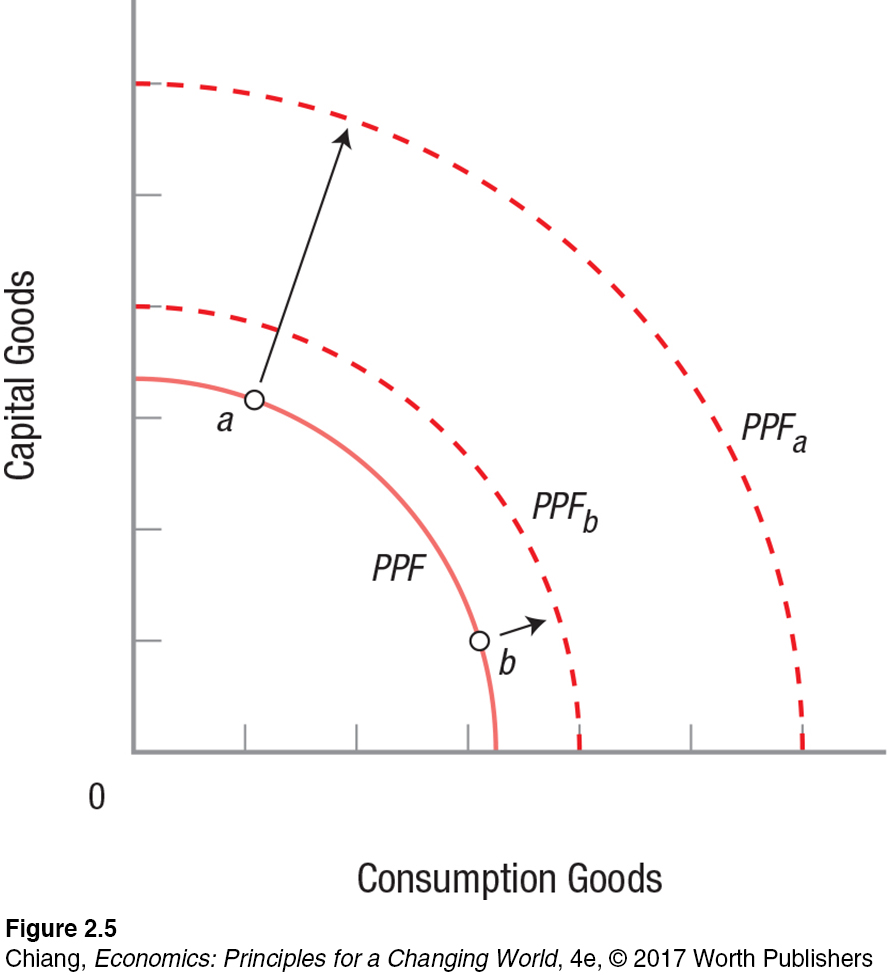

The production possibilities model and the economic growth associated with capital accumulation suggest a tradeoff. Figure 5 illustrates the tradeoff all nations face between current consumption and capital accumulation.

Let’s first assume that a nation selects a product mix in which the bulk of goods produced are consumption goods—

Contrast this decision with one in which the country at first decides to produce at point a. In this case, more capital goods such as machinery and tools are produced, while fewer consumption goods are used to satisfy current needs. Selecting this product mix results in the much larger PPF a decade later (PPFa), because the economy steadily built up its productive capacity during those 10 years.

Technological Change Figure 6 illustrates what happens when an economy experiences a technological change in one of its industries, in this case, the tablet industry. As the figure shows, the economy’s potential output of tablets expands greatly, although its maximum production of backpacks remains unchanged. The area between the two curves represents an improvement in the society’s standard of living. People can produce and consume more of both goods than before: more tablets because of the technological advancement, and more backpacks because some of the resources once devoted to tablet production can be shifted to backpack production, even as the economy is turning out more tablets than before.

This example reflects the United States today, where the computer industry is exploding with new technologies. Companies such as Apple and Intel lead the way by relentlessly developing newer, faster, and more powerful products. Consequently, consumers have seen home computers go from clunky conversation pieces to powerful, fast, indispensable machines. Today’s computers are more powerful than the mainframe supercomputers of just a few decades ago. And the latest developments in smartphones allow them to do much more than what powerful computers did a decade ago.

Besides new products, technology has dramatically reduced the cost of producing tablets and other high-

As you can see, there are many ways to stimulate economic growth. A society can expand its output by using more resources, perhaps by encouraging more people to enter the workforce or raising educational levels of workers. The government can encourage people to invest more, as opposed to devoting their earnings to immediate consumption. The public sector can spur technological advances by providing incentives to private firms to do research and development or underwrite research investments of its own.

ISSUE

Is the Ocean the Next Frontier? Land Reclamation and Underwater Cities

Can a city exist underneath the ocean surface? A team of engineers in Japan say that such cities can become a reality by 2030. They created a proposal for an underwater city that is powered by a process called ocean thermal energy conversion, in which power is generated from the differences in seawater temperatures at different depths. Can a self-

In fact, using the vast expanse of the ocean has already become a reality in some countries. Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates have built islands off of their coastlines using a process called land reclamation, in which sand is moved from other parts of the ocean to create new land above the ocean’s surface. More recently, China made headlines by building islands far from its coastline, which brings into question the role of property rights.

One of the concerns with underwater cities or land reclamation is who actually owns the right to live in the ocean. Because international watersbegin 12 nautical miles beyond a country’s coastline, some have questioned whether creating underwater cities or new islands in the ocean is merely a way for a country to acquire new territory, and subsequently the resources deriving from that territory, such as fish, natural resources, or a strategic geographic location for military purposes.

Summarizing the Sources of Economic Growth Economic growth is driven by many factors, as we have seen. A study by the Organisation for Economic Co-

1 The Sources of Economic Growth in the OECD Countries (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-

Increasing business investment (physical capital).

Increasing average education levels (human capital).

Increasing research and development.

Reducing both the level and variability of inflation.

Reducing the tax burden.

Increasing the level of international trade.

One important point to take away from this discussion is that our simple stylized model of the economy using only two goods gives a good first framework upon which to judge proposed policies for the economy. While not overly complex, this simple analysis is still quite powerful.

CHECKPOINT

PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

A production possibilities frontier (PPF) depicts the different combinations of goods that a fully employed economy can produce, given its available resources and current technology (both assumed fixed in the short run).

Production levels inside and on the frontier are possible, but those outside the curve are unattainable.

Because production on the frontier represents the maximum output attainable when all resources are fully employed, reallocating production from one product to another involves opportunity costs: The output of one product must be reduced to get the added output of the other. The more of one product that is desired, the higher its opportunity cost because of diminishing returns and the unsuitability of some resources for producing some products.

The PPF model suggests that economic growth can arise from an expansion in resources or improvements in technology. Economic growth is an outward shift of the PPF.

QUESTION: Taiwan is a small mountainous island with 23 million inhabitants, little arable land, and few natural resources, while Nigeria is a much larger country with 7 times the population, 40 times more arable land, and tremendous deposits of oil. Given Nigeria’s sizable resource advantage, why is Nigeria’s total annual production less than that of Taiwan’s?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Although Nigeria has significantly more natural resources and labor (two important factors of production) than Taiwan, these resources alone do not guarantee a higher ability to produce goods and services. Factors of production also include physical capital (machinery), human capital (education), and technology (research and development), all of which Taiwan has in great abundance. Thus, despite the lack of land, labor, and natural resources, Taiwan is able to use its resources efficiently and expand its production possibilities well beyond those of Nigeria.