INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL

In the previous chapter, we discussed reasons why some people are paid more than others, including discrimination in the labor market and the role of unions. But even if we put these important considerations aside, other factors may lead to wage differences, such as how much education one has. Previously, we had treated labor as a homogeneous input to simplify our analysis. In this section, we look at labor that has been enriched by training or education and how it affects the productivity of firms.

investment in human capital Investments such as education and on-

Is there a relationship between your earnings and your education? Let us first consider the role education and on-

Education and Earnings

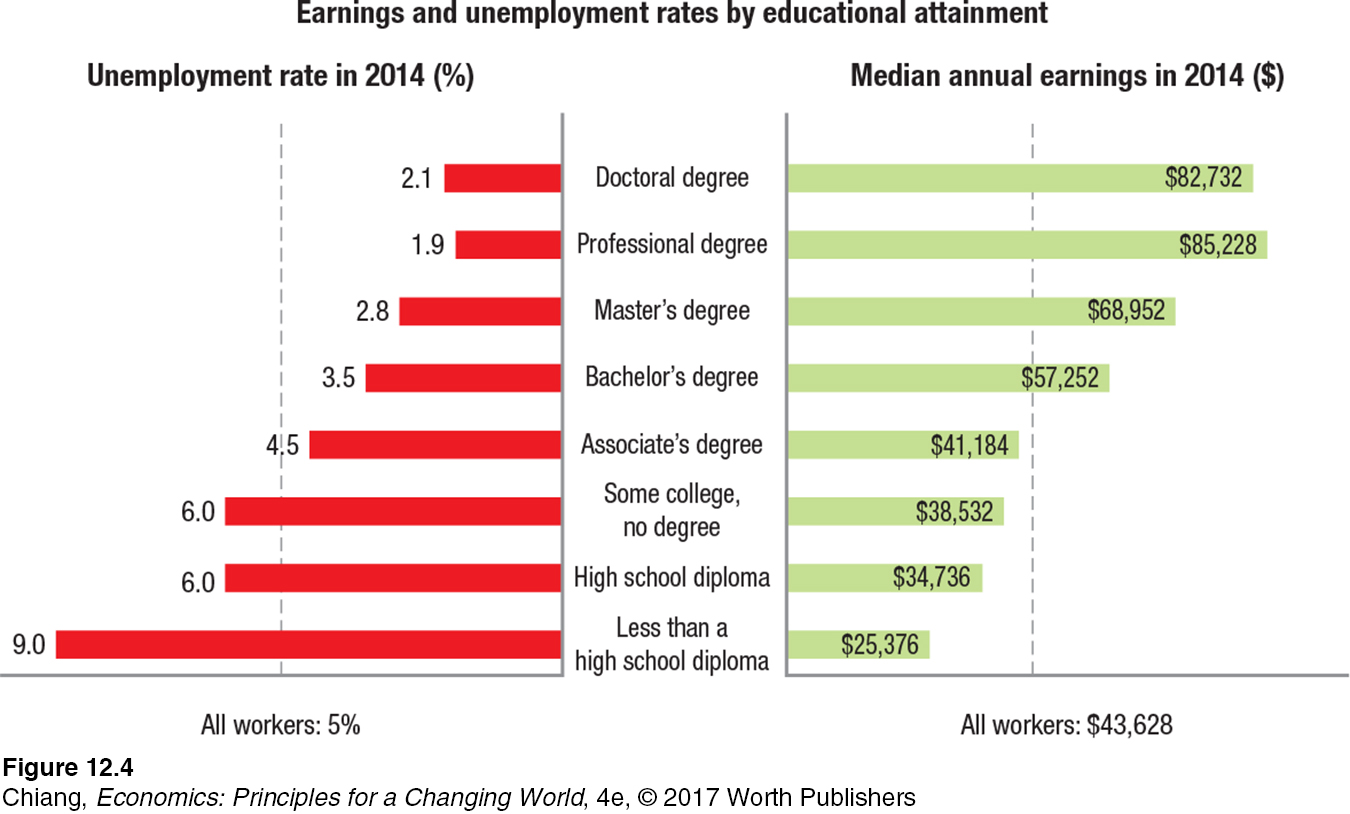

One of the surest ways to advance in the job world and increase your income is by investing in education. The old saying “To get ahead, get an education” still holds true. Figure 4 shows the median earnings and unemployment rates by highest degree earned for persons age 25 and over in 2014. It provides strong evidence that education and earnings are related.

Median earnings for those without a high school diploma were $25,376, while earnings for those completing high school were $34,736, a 37% increase. Getting a bachelor’s degree bumped median earnings up to $57,252, a 65% rise over those with only a high school diploma. Going on to get a professional degree moved median earnings all the way up to $85,228, almost 50% more than what a worker made with a bachelor’s degree alone. It’s also very evident that unemployment rates fall as one obtains more education. The unemployment rate for those without a high school diploma was 9%, while for those with a professional or doctoral degree, it was only about 2%. Clearly, acquiring more human capital makes a person more valuable to an employer, which results in more employment opportunities and higher earnings.

Figure 4 suggests that education is a good investment. But like any investment, future earnings must be balanced against the cost of obtaining that education. The costs of education must be borne today, but the earnings benefits do not arrive until later. Making optimal educational decisions therefore requires some tools to help evaluate investments in human capital markets.

Education as Investment

To keep our analysis simple, we will focus on the decision to attend college for four years. The basic approach outlined in this section will nonetheless apply to other investments in education or training.

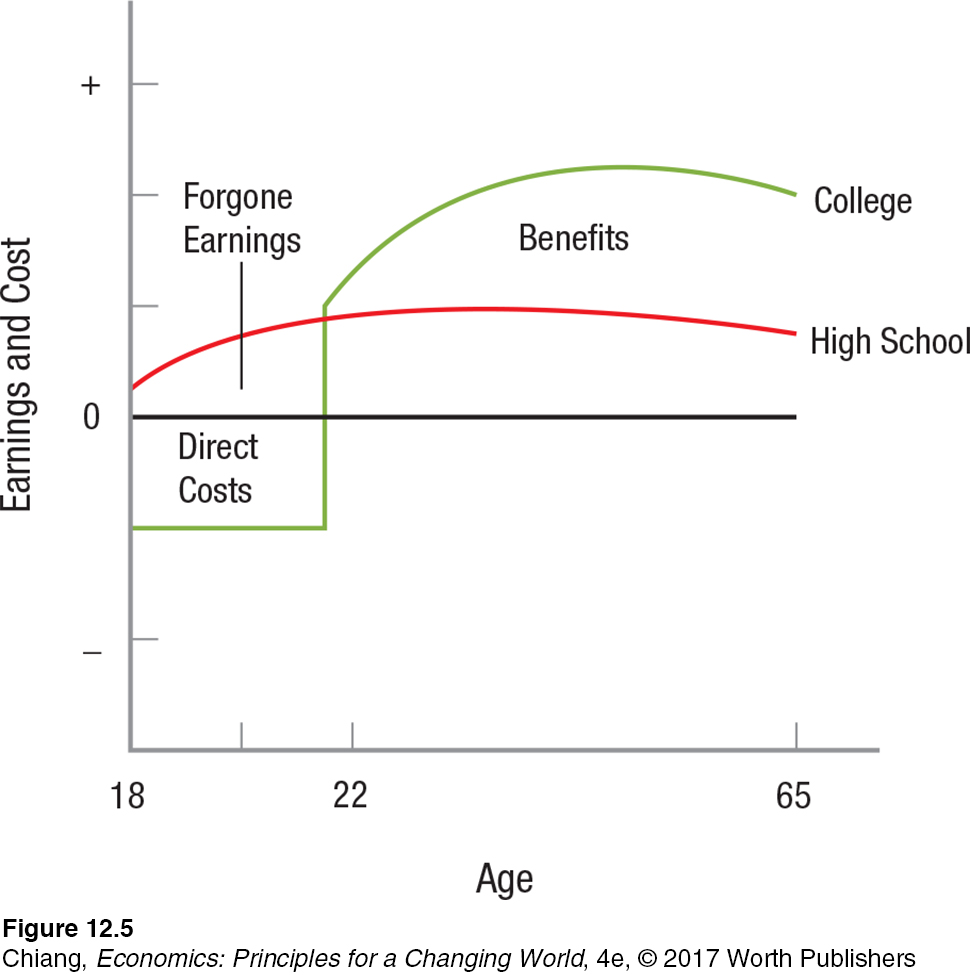

Figure 5 presents a stylized graph showing the benefits and costs of a college education. For simplicity, we will assume students go to college at age 18. If an individual chooses not to go to college, the high school earnings path applies: On leaving high school, the person enters the labor market immediately, and earnings begin rising along the path labeled “High School.” Note that the earnings are positive throughout the individual’s working life.

A college student immediately incurs costs in two forms. First, tuition, books, and other fees must be paid. These direct costs exclude living expenses, such as food and rent, because these must be paid whether one works or goes to college. Tuition varies substantially depending on whether one attends a private or public university.

Second, students give up earnings as they devote most or all of their time to their studies (and to the occasional party). These costs can be substantial when compared to the direct costs of an education at a state-

The benefits from a college degree show up as the difference in earnings from ages 22 to 65. If the return on a college degree is to be positive, this area must offset the direct costs of college and the forgone earnings. We must also keep in mind that a large part of the income high school and college graduates earn will not come until well into the future. For college graduates, this is especially important, because they will not see income for at least four years. How can we tell if this sacrifice is worth it? The fact that the median earnings of college graduates exceeded those of high school graduates by about 65% suggests a college education is worth it.

An alternative way to decide which of the two career paths is best is to compute the rate of return on a college degree. If the annual return on a college education over the course of one’s working life is 10% a year, the earnings of the college graduate in middle age will exceed those of the high school graduate by enough to generate a 10% return. A lower return would mean that the difference in earnings is smaller, while a higher return suggests the difference in earnings is greater. An extensive study1 of rates of return to higher education in nearly 100 countries put the average return at nearly 20%. That is, college graduates around the world earn, on average, nearly 20% more per year over the course of their working lifetime than high school graduates, taking into consideration all of the costs of going to college.

1 G. Psacharopoulos and H. Patrinos, “Returns to Investment in Education: A Further Update,” Education Economics, 2004.

Equilibrium Levels of Human Capital

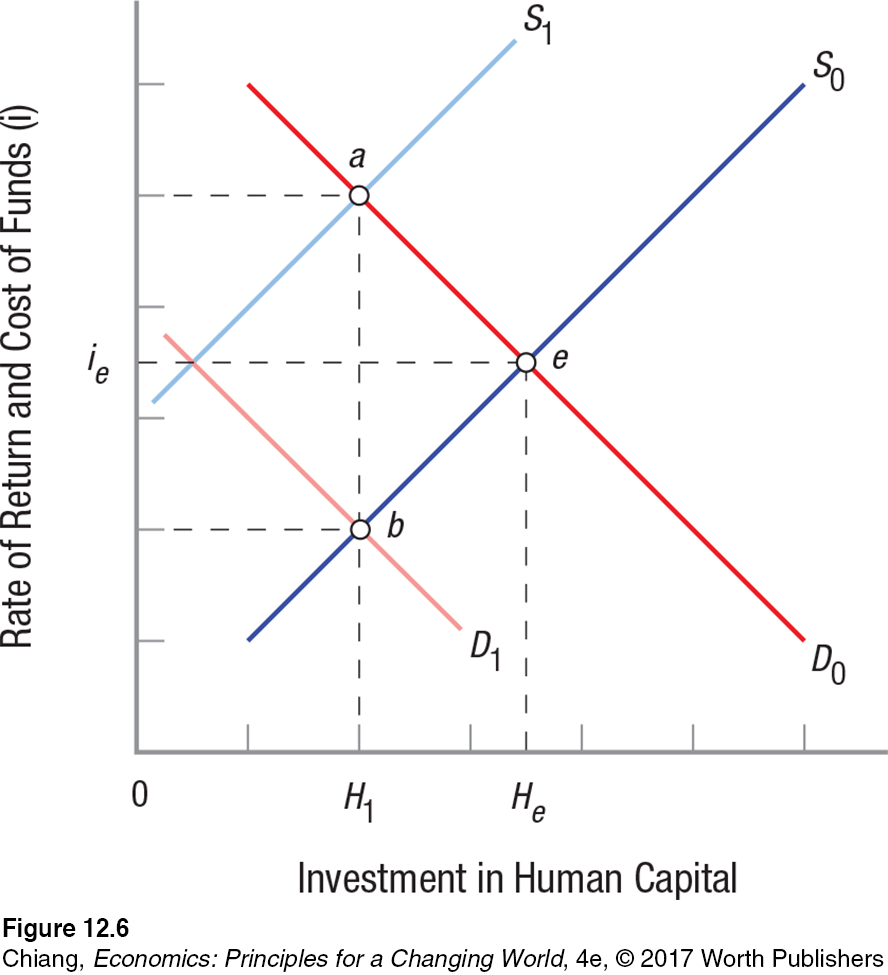

Each of us must decide how much to invest in ourselves. This decision, like so many in economics, ultimately depends on supply and demand, in this case, the supply of, and demand for, funds to be used for human capital investment. A hypothetical market for human capital is shown in Figure 6. In this scenario, “price” is the percentage rate of return on human capital investments and the interest cost of borrowing funds.

The demand for human capital investment slopes down and to the right, reflecting the diminishing returns of more education and that more time in school leaves you less time to earn back its costs. Students pursuing a Ph.D. or a medical degree are often into their thirties before they can begin paying back their student loans. As a result, they require higher salaries to bring up their rates of return above those of college-

The supply of investable funds, meanwhile, is positively sloped, because students will use the lowest-

With demand (D0) and supply (S0), equilibrium in this market occurs at point e. Human capital investment is equal to He, with the rate of return equaling the interest rate (ie). Notice that reducing the supply of funds, or shifting the supply curve to S1, will increase interest rates and the cost of investment. This results in lower investments in education. Similarly, anything reducing the demand for funds, or shifting the demand curve to D1, will result in reduced human capital investment. Let us briefly consider some of the factors that might cause these curves to shift.

The most important factor determining the supply of investable funds for students consists of family resources. Students from well-

Another factor influencing human capital investment is discrimination. Assume D0 represents the demand for human capital investment for individuals facing no discrimination in the labor market. If these same people were to face a reduced wage in the market from wage discrimination, their demand for education would fall to D1, reflecting the reduced return on investment in human capital. A similar decline in demand would result if the choice of jobs is limited by occupational discrimination.

The demand for human capital is also influenced by an individual’s abilities and learning capacity: The more able the person, the larger the expected benefits of human capital investment.

Implications of Human Capital Theory

Individuals are more productive because of their investment in human capital, and thus they are capable of earning more during their working lives. Because younger people have longer earning horizons, they are more likely to invest in human capital and education. As workers get older and gain labor market experience and higher wages, their opportunity costs for attending college grow larger, while their potential post-

The greater the market earnings differential between high school and college graduates, the more people will attend college, because a higher earnings differential raises the return on a college education. Similarly, reductions in the cost of education lead to greater educational investment.

Further, the more an individual discounts the future—

Human Capital as Screening or Signaling

screening or signaling The use of higher education as a way to let employers know that the prospective employee is intelligent and trainable and potentially has the discipline to be a good employee.

Human capital theorists see investments in human capital as improving the productivity of individuals. This higher productivity then translates into higher wages. There is another view of why higher educational levels lead to higher wages: Higher education acts as a screening or signaling device for employers.

Economists who advocate this view concede that some education will undoubtedly lead to higher productivity. But these economists argue that higher education is largely an indicator to employers that the college graduate is trainable, has discipline, and is intelligent. In their view, the job market is one big competition in which entry-

Most economists, however, doubt the theory that screening is the only purpose served by higher education. If it were, the high costs of college education and the higher wages employers must pay college graduates would create tremendous incentives for workers and employers to develop an alternative, less expensive screening device.

ISSUE

A Class with 10,000 Students? MOOCs and Human Capital

The format by which college education is delivered has changed significantly over the past decade. Traditionally, attending a class required physically going to a classroom and interacting with a professor and fellow students. The Internet has changed that, as nearly every institution of higher learning now offers online education in some form. And even the way online courses are delivered has changed. Technologies such as lecture capture and live chat rooms permit professors to deliver content online much like one would in a classroom, allowing students to interact with each other virtually.

Innovation in online education has made a college degree attainable for those whose circumstances do not allow for a traditional on-

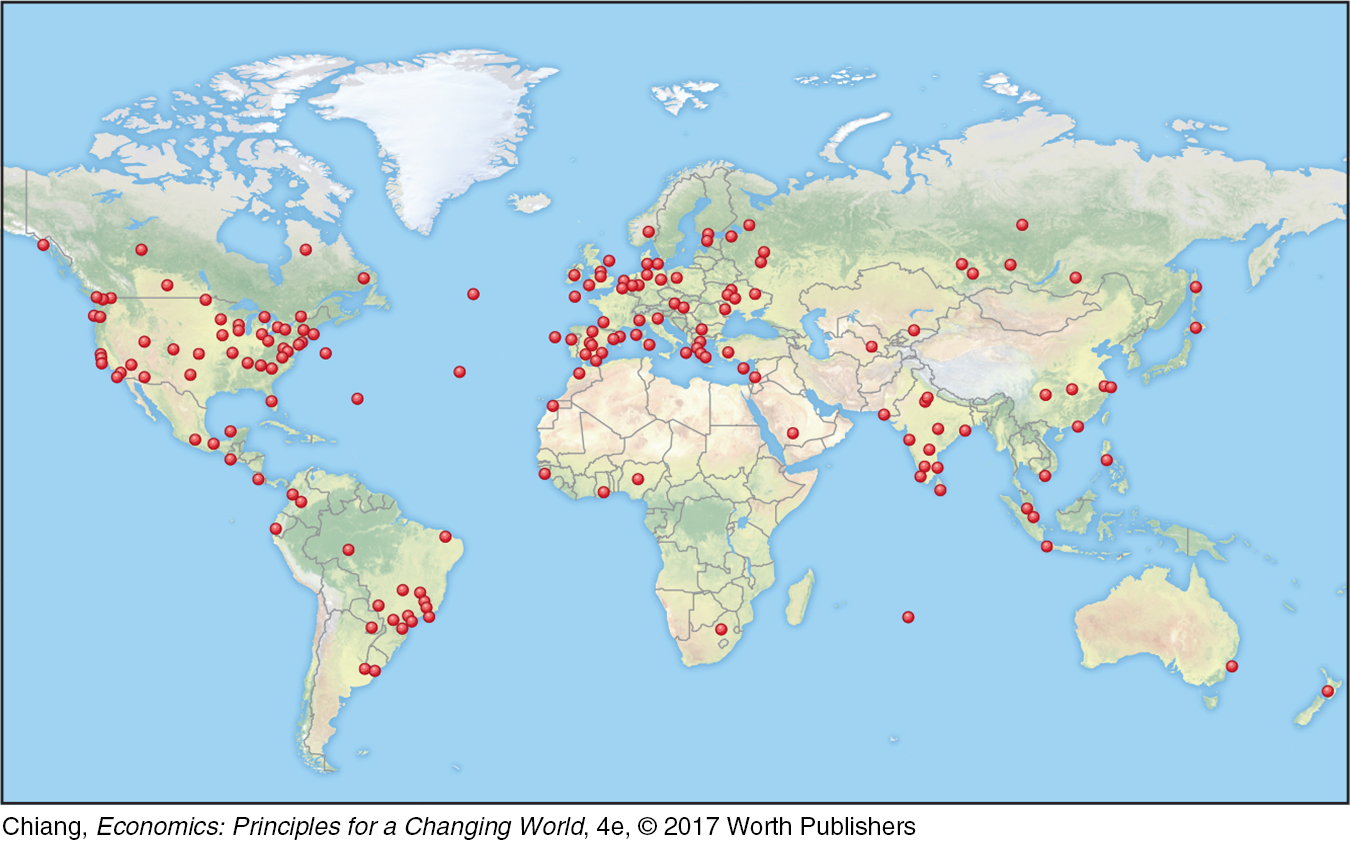

One of the benefits of online education is that classroom capacities no longer exist. As a result, some colleges have created super-

The ability to take online courses for free has allowed persons from around the world to create human capital that otherwise might not be possible, especially in the most rural and poor areas of the world. All that is required is a computer with Internet service, which are becoming increasingly available in even the poorest nations. Over time, opportunities such as these will allow aspiring students from anywhere in the world to achieve a college education without ever needing to leave home.

On-the-Job Training

on-

On-

College internship programs are a good example of OJT that offers firms an extended look at potential employees while providing students with a look at several different firms and industries before graduating and entering the job market.

Today, spending on OJT exceeds $100 billion a year, including training costs and the wages paid to employees during training. The costs of OJT are usually borne by employers, but workers may bear some of the costs through reduced wages during the training period. Firms benefit from OJT by gaining more productive workers, and workers gain by becoming more versatile, and thus more competitive, in labor markets. Because all OJT entails present costs meant to yield future benefits, firms choose to provide OJT if the returns from this investment compare favorably to other investment alternatives.

Investments in human capital go a long way toward explaining why people are paid different wages. Education and earnings are closely related. Human capital theorists believe that this is because education and productivity are closely related. For this reason, firms are willing to pay higher wages to individuals with greater amounts of human capital. For industries that require advanced skills, such as in computer programming, aerospace, and biotechnology (just to name a few), human capital is difficult if not impossible to replace with ordinary labor. Therefore, human capital is considered a capital input in the factors of production.

CHECKPOINT

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL

Investment in human capital includes all investments in human beings such as education and on-

the- job training. There is a positive relationship between education and earnings.

The rate of return to education is computed by comparing the streams of income from two different levels of education.

The greater the wage differential between two levels of education, the more people will pursue that next level of education.

Higher education may just be a screening or signaling device telling potential employers that this individual is trainable, has discipline, and is intelligent.

Firms are willing to provide on-

the- job training when the future returns to human capital investment in terms of increased productivity to the firm exceed the costs of that training.

QUESTIONS: If a country decided, as part of an immigration reform package, to restrict immigration only to those with college degrees, and thus decided to allow only 500,000 foreigners a year to enter, what would happen to the rate of return on college education? Alternatively, if, as part of a reform package, 500,000 low-

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Letting in a large number of college-