PUBLIC GOODS

We saw in the previous section that externalities can lead to markets not providing the socially efficient amount of a good at the optimal price. Either too much or too little of the good is produced, or it is offered at too high or too low a price, leading to a market failure. The presence of externalities is one cause of market failure. This section looks at two other causes of market failure that arise when no individual or firm is able to claim ownership of a product. These goods and services are called public goods and common property resources.

What Are Public Goods?

public goods Goods whose consumption by one person cannot diminish the benefit to others of consuming the good (i.e., nonrivalry), and once they are provided, no one person can be excluded from consuming (i.e., nonexclusion).

nonrivalry The consumption of a good or service by one person does not reduce the utility of that good or service to others.

nonexcludability Once a good or service is provided, it is not possible to exclude others from enjoying that good or service.

Pure public goods are nonrival in consumption, and exhibit nonexcludability. Nonrivalry means that the consumption of a good or service by one person does not reduce the utility of that good or service to others. Nonexcludability means that it is not possible to exclude some consumers from using the good or service once it has been provided.

By way of contrast, a can of Coke is a rival product. When you drink a can of Coke, no one else can drink that same can. Airline flights exhibit excludability—

| TABLE 2 | TAXONOMY OF PRIVATE AND PUBLIC GOODS | |||

| Property Rights | ||||

| Characteristics of Goods | Exclusive | Nonexclusive | ||

| Rival |

Pure private good

|

Common property resource

|

||

| Nonrival |

Public good with exclusion

|

Pure public good

|

||

free rider An individual who avoids paying for a good because he or she cannot be excluded from enjoying the good once provided.

Consumers cannot be excluded from a public good once it is provided; therefore, they have little incentive to pay for the good in question. Instead, most will essentially be free riders. Think of the lighthouse again. If you have a ship and cannot be excluded from the benefits the lighthouse provides, why should you contribute anything to the lighthouse’s upkeep? But if everyone took this position, there would be no support for the lighthouse, and it would go into decline. With free riders, private producers cannot hope to sell many units of a good, and thus they have no incentive to produce it. Private markets will therefore fail to provide public goods, even if the goods are things everyone would like to see produced. This is why the government or special interest groups must get involved in the provision of products and services that have significant public good characteristics.

The Demand for Public Goods

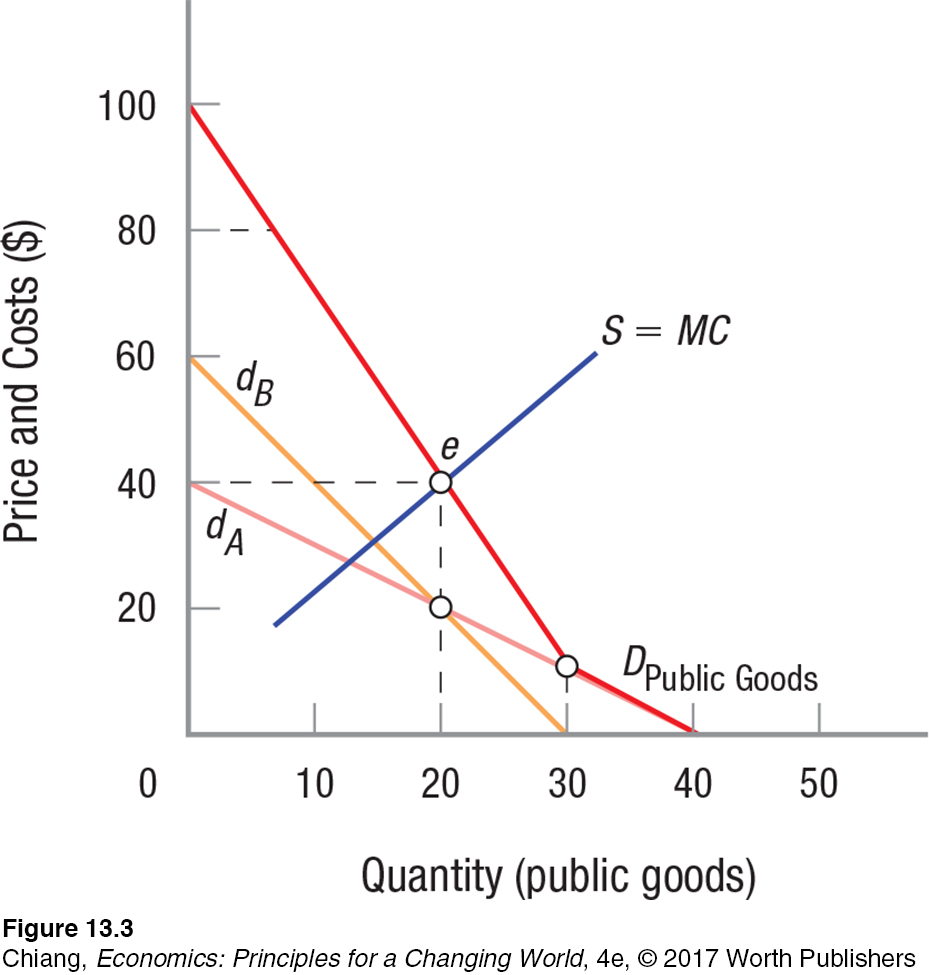

Assessing the public’s demand for public goods is clearly different from that of private goods where we found market demand by horizontally summing private demands. But the fact that once a public good is supplied, no one can be excluded from consuming it, and one person’s consumption does not affect another’s, plays a crucial role. Figure 3 provides a solution to finding the demand for public goods.

Figure 3 shows demand for a public good by two different consumers. Individual A wants none when the price is $40 and is willing and able to buy 40 units when the price approaches zero. Individual B wants none when the price is $60 and only is willing to buy 30 units when the price nears zero. Because each consumer can consume any given amount of a public good at the same time, the total demand for a public good is found by summing the individual demands vertically. To see why, consider when both individuals demand 20 units. This is the point at which the two demand curves cross, and both are willing to pay $20 for 20 units. Thus, total willingness-

Notice how this differs from our discussion of market demand curves for private goods. For private goods, others could be excluded from consuming any good we bought; therefore, demands were horizontally summed. In contrast, with public goods, exclusion is not possible; therefore, both individuals can consume the good simultaneously, and market demand is found by summing vertically. Market demand for public goods is really a willingness-

Optimal Provision of Public Goods

Providing the optimal amount of public goods is easy in theory and is illustrated in Figure 3. The supply of public goods is equal to the marginal cost curve (S = MC) shown in the figure. Just like the competitive market equilibrium we covered earlier, optimal allocation is where MC = P, and in this instance, it is 20 units of the good at a total price of $40 (point e). In this example, the taxes are split equally between individuals A and B. Determining how much tax each person should (or would be willing to) pay is hampered by the fact that once the public good is provided, no one can be excluded; therefore, individuals will be unwilling to reveal their true preferences for the good because it might mean that they would have to pay a higher tax.

In reality, providing public goods such as national defense involves the political process. This means that politicians, bureaucrats, special interest groups, and many others generate the decisions on how much of any particular public good to provide. Since the demand for a public good represents the benefits to society and the supply curve represents society’s costs, equating marginal benefits and marginal costs yields the optimal amount. But estimating the demand (benefits) from public goods and their costs can be a complex process. Most people desire the benefits of a strong military, but few enjoy paying the taxes required to pay the cost. Because people cannot be excluded from the good once provided, they have little incentive to reveal their true preferences, making this type of market failure difficult to overcome.

Common Property Resources

“tragedy of the commons” Resources that are owned by the community at large (e.g., parks, ocean fish, and the atmosphere) therefore tend to be overexploited because individuals have little incentive to use them in a sustainable fashion.

Commonly held resources are subject to nonexclusion but are rival in consumption. The market failure associated with such resources is often referred to as the “tragedy of the commons.”3 The tragedy here is the tendency for commonly held resources to be overused and overexploited. Because the resource is held in common, individuals race to “get theirs” before others can grab it all.

3 Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, 1968, pp. 1243–

One example of commonly held resources giving rise to problems involves oil fields. Oil reservoirs often span the subsurface property of many landowners. Because oil reservoirs are regarded as common property, each landowner has an incentive to drill as many wells as possible and to pump out oil as rapidly as possible. Having too many wells pumping too quickly, however, reduces the oil field’s water and gas pressure, thus reducing the total recoverable oil from the reservoir. Each owner’s decision to drill a well therefore imposes an external cost on the other owners of land over the reservoir. At one point, this problem grew so severe that it resulted in passage of the 1935 Connally “Hot Oil” Act. This act restricted drilling, regulated the number and location of oil wells, and capped pumping rates.4

4 Daniel Yergin, The Prize (New York: Simon & Schuster), 1991.

Life at the Top of the Rock: Protecting the Barbary Macaques

How are Barbary macaques able to roam freely in the tiny British territory of Gibraltar when they have been completely driven away everywhere else in Europe?

The Barbary macaque is a tailless monkey with origins in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco and Algeria, and in Southern Europe. Decades of logging, however, have decimated the natural habitat to a point that the macaques have become an endangered species. Today, Barbary macaques no longer roam freely in Europe—

Gibraltar is a tiny English enclave at the southern tip of Spain, across the Strait of Gibraltar from Morocco. At barely 2 square miles, Gibraltar is so tiny that its airport runway crosses the main highway, halting auto traffic every time an airplane lands or takes off.

Why would this tiny tourist destination be home to hundreds of freely roaming Barbary macaques?

An ideal natural habitat for Barbary macaques has been bolstered by Gibraltar’s laws that have protected the species as a public good. Gibraltar is home to the Rock, a towering monolith of limestone that serves as a nature preserve where Barbary macaques have thrived because of its popularity as a tourist attraction. The macaques have adapted to life on the Rock, allowing tourists to approach them with remarkable ease. It is the only population of wild monkeys that remains in Europe, and the citizens of Gibraltar have taken great effort to ensure their well-

The protection of Barbary macaques in Gibraltar is a public good because the ability to see and appreciate these monkeys in the wild is a benefit that can be experienced by everyone without exclusion or rivalry. The cost of maintaining the population had long been paid for by the government and managed by the British military stationed in Gibraltar. More recently, their care has been transferred to a nonprofit organization called the Gibraltar Ornithological & Natural History Society.

As long as people are willing to contribute to their upkeep, Barbary macaques will remain a unique attraction to locals and tourists for years to come.

GO TO  TO PRACTICE THE ECONOMIC CONCEPTS IN THIS STORY

TO PRACTICE THE ECONOMIC CONCEPTS IN THIS STORY

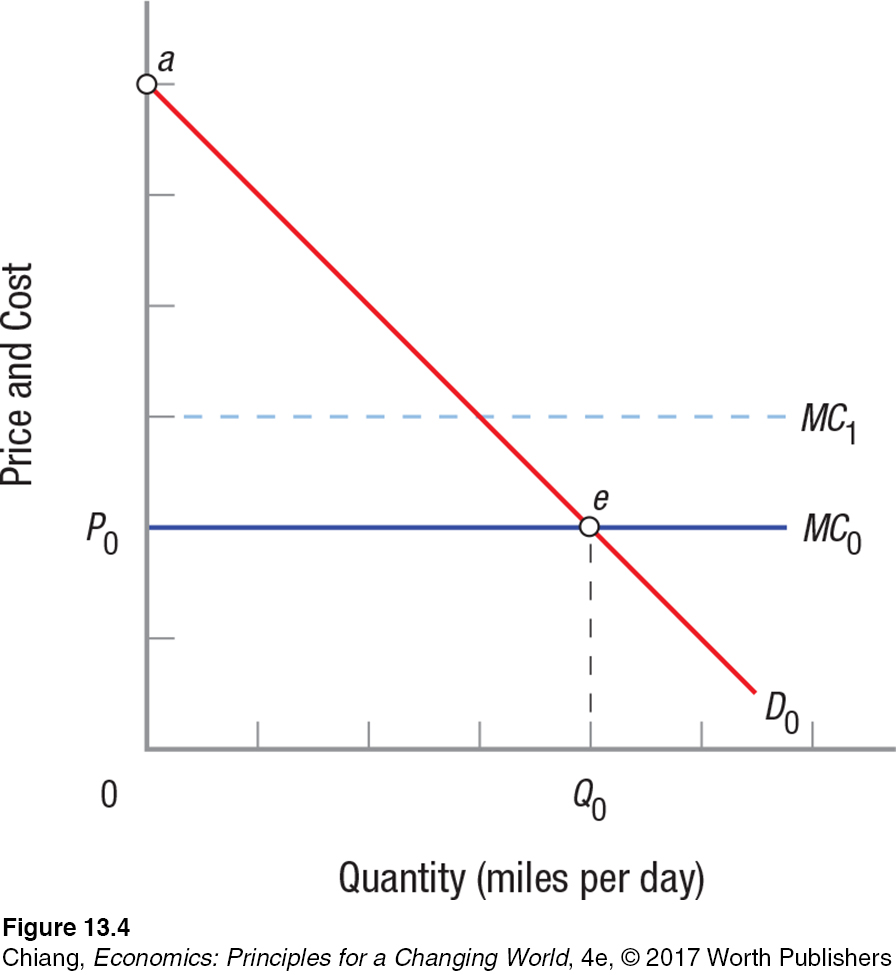

Road congestion is another illustration of the “tragedy of the commons.” Figure 4 shows a market for usage of a road that is fully used and is right at the tipping point before becoming congested. In Figure 4, demand for driving on this road is D0, and the marginal cost to use the road—

Now assume that a new driver begins using the road. This increases the marginal cost of driving to MC1 for everyone, because the tipping point has been passed, and the road is now congested. Consumer surplus shrinks because of overuse of the commons. Note that the new driver did not take these external costs into consideration; the driver assumed that the marginal cost would be equal to MC0, not MC1.

Possible solutions to common property resource problems involve establishing private property rights, using government policy to restrict access to the resource, or informal organizations that restrict each user’s benefits from the resource. Reduced congestion, for example, could be achieved by raising the tax on gasoline, subsidizing bus or rapid transit travel, or privatizing roads and allowing the owners to charge tolls.

The optimal provision of public goods, whether pure public goods or common property resources with significant public goods characteristics, is a significant challenge faced by society. Individuals tend to act in their self-

Health Care as a Public Good

Among the most contentious recent issues has been the expansion of health care access with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. Although health care services are guaranteed by the government to those serving in the military along with veterans, those over the age of 65 with Medicare, and those who fall below certain income limits that qualify for Medicaid, most Americans rely on the private insurance market for their health care services. Much of this insurance is paid for by employers of full-

asymmetric information Occurs when one party to a transaction has significantly better information than another party.

One problem with private health care provision and private insurance markets is asymmetric information, when one party knows more about a situation than another. For example, individuals know more about their daily health habits than private insurers, and might try to hide unhealthy habits. Doctors know more about medical conditions than their patients, leading some to order excessive medical tests or prescribe more expensive treatment options than what might be necessary. A consequence of asymmetric information is an increase in the cost of health care resulting from inefficiencies in delivering health care, which leads to higher insurance prices that become unaffordable to many. Addressing the problem of asymmetric information requires greater transparency in medical records to prevent patients and doctors from exploiting information to their advantage. Otherwise, it may lead to greater escalation in the cost of health care, as the following example shows.

Suppose that consumers with bad habits (such as poor eating habits, lack of exercise, aggressive driving, or a penchant for high-

Because of the growing number of Americans who either did not qualify for insurance or chose not to purchase it, the ACA was passed in 2010, though not without tremendous controversy and subsequent attempts by Congress to eliminate it. The aim of the ACA is to reduce the percentage of Americans without health care coverage. This is accomplished through many rules, such as preventing insurance companies from refusing customers due to preexisting conditions (such as a previous bout of cancer that would have previously disqualified a person from obtaining affordable insurance), removing lifetime limits on coverage, providing subsidies to make insurance more affordable, and requiring all Americans to buy insurance or face a tax penalty at the end of the year (commonly known as the individual mandate). From 2010 to 2016, the uninsured rate fell from 16% to 11%.

The ACA remains controversial because of the individual mandate that forces all consumers to buy insurance, even if they do not want it. Mandated health care has many characteristics of public goods, something that all persons have access to and a service that one cannot opt out of no matter why.

ISSUE

The Resurgence of Nearly Eradicated Diseases—

Prior to the 1960s, cases of whooping cough and measles were common among children, with up to 200,000 cases of whooping cough and more than a million cases of measles in the United States (and likely much more due to underreporting), resulting in hundreds of deaths each year.

By the 1970s, advances in childhood vaccinations led to a dramatic reduction in cases of measles, whooping cough, polio, and other illnesses, and the eradication of smallpox. Such progress in public health research led to decades of progress in ensuring that all children receive access to affordable immunizations.

Over time, however, complacency has arisen. Some parents began to worry that the perceived risks of vaccines outweighed their benefits. Fears of vaccines rose when a 1998 study published in The Lancet claimed a link between vaccines and autism. Although this study was eventually determined to be fraudulent, leading The Lancet to retract the study and the doctor behind the study to be stripped of his medical license, that did not slow down a growing number of parents choosing not to vaccinate their children. This led to grave outcomes, as cases of whooping cough and measles surged in recent years, with 667 confirmed cases of measles and 32,971 cases of whooping cough in the United States in 2014.

The effect of immunizations is one that highlights the importance of health care as a public good. When the entire population is free of a disease, choosing to forgo vaccinations means one will likely not be exposed to an illness. However, once enough people choose not to vaccinate, the immunity of the population (called herd immunity) fades. In other words, people who choose not to vaccinate depend on others not to spread diseases. They free ride on the willingness of others to get vaccinated. But like all public goods, when the number of free riders increases, an optimal provision of the public good fails. The resurgence of nearly eradicated diseases is an example of the consequences that can result.

Why would a government force its citizens to buy health insurance? First, like other public goods, it is subject to the free rider problem. Those without health insurance often use hospital emergency rooms for illnesses and accidents because many laws prevent caregivers such as hospitals from denying emergency care, regardless of ability to pay. The cost is borne by caregivers, who pass this on in the form of higher prices for everyone else. Second, much like other public goods such as clean air, fire department services, or elementary education, health care provides societal benefits such as improved productivity and earlier diagnosis of severe illnesses, which allows for greater treatment options and lower costs.

The ACA is likely to remain unpopular among many for some time. This is common whenever a debate ensues on the best approach to providing public goods. In the long run, however, once consumers become accustomed to the benefits created by the ACA, they will be less likely to accept those same benefits being taken away.

CHECKPOINT

PUBLIC GOODS

Pure public goods are nonrival in consumption, and once the good is provided, no one can be excluded from using it.

The demand for public goods is found by vertically summing individual demand curves.

Optimal provision of public goods is found where the marginal benefit of public goods (demand) is equal to the marginal cost of provision.

Common property resources have the characteristics of nonexcludability but are rival. This typically leads to overuse and overexploitation.

Health care is an example of an industry with public good characteristics in which asymmetric information and free ridership are common.

QUESTIONS: On most college campuses, the use of the recreation center is open to all registered students without an additional fee. The cost of running the recreation center typically is paid for by an activity fee paid by all students, regardless of whether they use the facilities or not. In what ways does your campus recreation center resemble a public good? In what ways does it not?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

If the recreation center on campus allows all students to use it without an additional fee, it resembles some of the characteristics of a public good. Although it can exclude nonstudents from the facility, it is open to all students. Therefore, it is partially nonexcludable. However, if too many students use it, it can become crowded, resembling more of a common property resource.