Monopoly

9

Learning Objectives

9.1 Describe the characteristics of a monopoly and market power.

9.2 Describe the ways in which firms maximize market power using barriers to entry.

9.3 Use monopoly market analysis to determine the equilibrium level of output and price for a monopoly.

9.4 Describe the differences between monopoly and competition.

9.5 Describe the different forms of price discrimination.

9.6 Describe the different approaches to regulating a natural monopoly.

9.7 Relate the history and purpose of antitrust legislation to monopoly analysis.

9.8 Apply concentration ratios and the Herfindahl–

9.9 Describe the conditions of a contestable market and its significance.

When was the last time you used Google to search for information? How about YouTube, Gmail, Google+, Google Docs, Chrome, Google Maps, Waze, or any Android app? If you have used any of these services within the past 24 hours, you’re in the majority of Americans who rely on at least one of over one hundred Web-

Although Google users rarely pay to use any of its Web services, the market value of the company as of April 2016 was over $500 billion, or about the same total market value of Walmart (with its 12,000 stores), McDonald’s (with its 35,000 restaurants), and Coca-

The answer is that Google sells advertising services, and lots of them (over $50 billion in sales in 2015), to companies worldwide that pay to have their Web sites show up more prominently on Web search results, or along the top and sides of Google’s “free” services. Incredibly, Google charges some companies $50 every time someone clicks on their ad links, although the average price is closer to $1. But with over 2 billion Google users worldwide, it doesn’t take much to bring in a significant amount of revenue.

How is Google so profitable? In the previous chapter, we constructed a model of perfectly competitive markets in which many sellers compete against one another for the business of many buyers. This model assumed that different firms sell almost identical products, produce at the point where price equals marginal cost, and face no barriers to entry, entering or exiting industries as profit opportunities rise and fall. Keep in mind that firms in perfectly competitive markets have no pricing power. They are price takers, accepting the market price as given—

Although Google has competitors, such as Yahoo!, Bing, and others, Google commands a dominant share (over 70%) of the search engine market. Unlike perfectly competitive firms, Google has a lot of market power. By market power, we mean the ability to have some control over price.

In reality, most firms have some market power. You see this every day. The cleaners located at the train station is more convenient than the cleaners located in town, at least for those taking the train, and therefore can get away with charging a little more for cleaning and pressing shirts or skirts. A gas station located near a highway can charge a little more than a gas station a mile away.

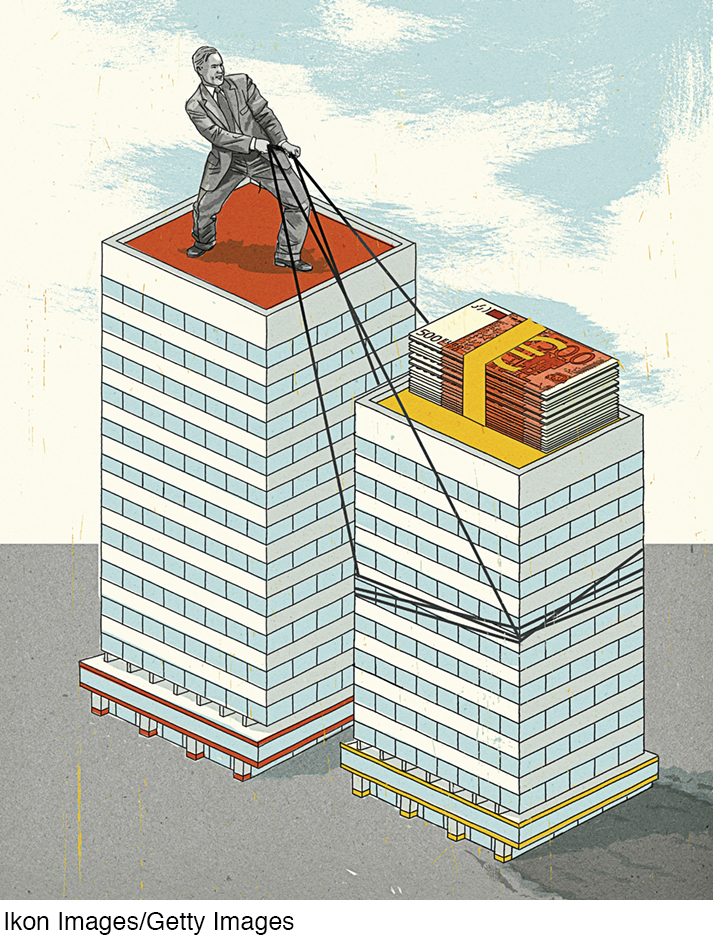

As we move down the market structure spectrum from the perfectly competitive firms on one end to the monopolistically competitive firms, and then to the oligopolies, finally ending up with monopolies at the other end, we will see that firms obtain more and more market power. We will see why firms want to be monopolies.

What is a monopoly? When a single company is the only firm in the industry, the company is a pure monopoly. Google is not a pure monopoly because it has some competitors, but it is so dominant that it comes close. In both situations, the economic analysis is similar, and for simplicity we refer to these firms as monopolies, even if they are not in the purest sense.

This chapter studies the theory of monopoly, which is at the other market structure extreme from the competitive model. Whereas the competitive model is in the public interest, we can guess at the outset that monopolies generally are not. We will see why monopolies exist and how they act. Then we will see what it means to have market power, the ability to set price, and why monopolies have maximum market power. After that, we will see what can be done to mitigate the powers of monopolies that must exist, and how the government tries to prevent monopolies from arising in the first place.

We also study how monopolies can be beneficial. Some monopolies create economies of scale or provide product innovation and creativity. Many of today’s new technologies and pharmaceuticals would never have been created if firms with complete market power did not exist. These products create benefits to users that offset some of the inefficiencies firms with market power pass on to consumers through higher prices. As with all economic analysis, costs and benefits must be weighed to determine the effect on consumers and producers, and the study of monopoly is no different.