Preparing for an Interview

Preparing for an interview entails a number of steps for both the interviewer and the interviewee. An interviewer will need to define the purpose of the interview, develop an interview protocol, and determine questions to ask. If you’re being interviewed, you’ll want to anticipate the interview purpose as well as the types of questions you might be asked.

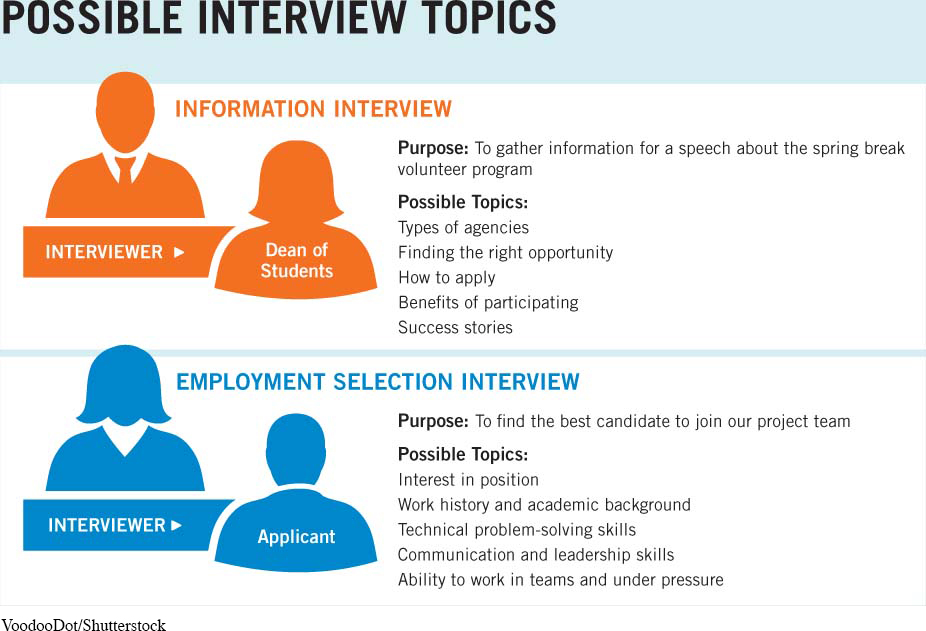

Defining Your Purpose. To prepare for an interview you’ll be conducting, start by defining your purpose. This helps you identify what topics to cover. Imagine that you’re preparing a persuasive speech about your school’s spring break volunteer program. You might arrange to interview the dean of students to find out about volunteer opportunities, program requirements, and the benefits of doing community service. If you’re interviewing job applicants, your purpose is to find the best candidate by exploring such topics as each applicant’s work history and relevant experience (see Table A.1). Having a clear purpose for the interview gives focus and structure to the topics that will be discussed.

If you’re going to be interviewed, you should also take time beforehand to consider what topics might be covered so you can be prepared to answer questions. For instance, if you’re going to be interviewed for a job, be ready to talk in depth about how you’ve successfully applied your skills in previous work settings.

Developing an Interview Protocol. When preparing to conduct an interview, you should also develop an interview protocol—a list of questions, written in a logical order, that guide the interview. Like a preparation outline for a speech, preparing an interview protocol in advance will show whether you are including all the topics you need and arranging them in a way that makes sense. For example, if you are interviewing a job candidate, you may want to start with general questions (“Tell me about your work history”) before moving to more specific questions (“What project did you find most challenging?”).

If you plan on asking highly specific or difficult questions, think about when to bring those up. Asking them too early in an interview could make the interviewee uncomfortable or confused. Depending on the type of interview, that could make it difficult to get the information you need. It’s usually easier to start with less personal, or “safe,” questions (“What did you like most about your last job?”), and then move on to questions about emotional or difficult topics (“What was your biggest mistake?”).

When you are an interviewee, you should be responsive to the order of questions that you’re asked. Allow the interviewer to ask each question in turn, and answer the question completely. Avoid perceptual errors by trying to second-

Determining Questions to Ask. Questions are the heart of any interview. But not all questions have the same purpose. You can use questions to introduce a new topic, get clarification, or ask for additional details. Even the way you phrase a question influences the answers you get. So when you’re developing your interview protocol, consider the different types of questions you can ask.

You can introduce topics or new areas within a topic by using primary questions. These questions guide the conversation and are written into the interview protocol. For example, “Dr. Ghent, let’s talk about volunteer service and leadership. How does volunteering help students develop their leadership skills?”

You can follow up on answers given by an interviewee with secondary questions. These questions aren’t usually written into the interview protocol; instead, they evolve out of the conversation. A secondary question can help you clarify vague answers (“When you say ‘students increase their social intelligence,’ what do you mean?”) or probe further into a response (“Tell me more about your summer work as a lifeguard”). Often a secondary question is nothing more than a brief comment to encourage the interviewee to continue answering the question (“Then what happened?” or “How did you resolve that?”). To use secondary questions successfully, use active listening skills to ensure you understand the interviewee’s answers. If you’re preoccupied or distracted, you’ll miss opportunities to clarify or probe answers further.

How you phrase a question can also affect the way interviewees answer. Open questions give interviewees a lot of freedom in formulating their responses. For example, “How do students benefit by volunteering during their spring break?” could be answered in any number of ways. On the other hand, closed questions usually require only a yes or no response, which limits the range of possible answers. For instance, “Can you operate a forklift?” Use open questions when you want to generate more detailed responses. Closed questions help you move quickly through topics during the interview and swiftly determine whether you’ve gathered critical information. If someone applying for a job as a forklift operator can’t operate the equipment, you’d want to know that immediately.

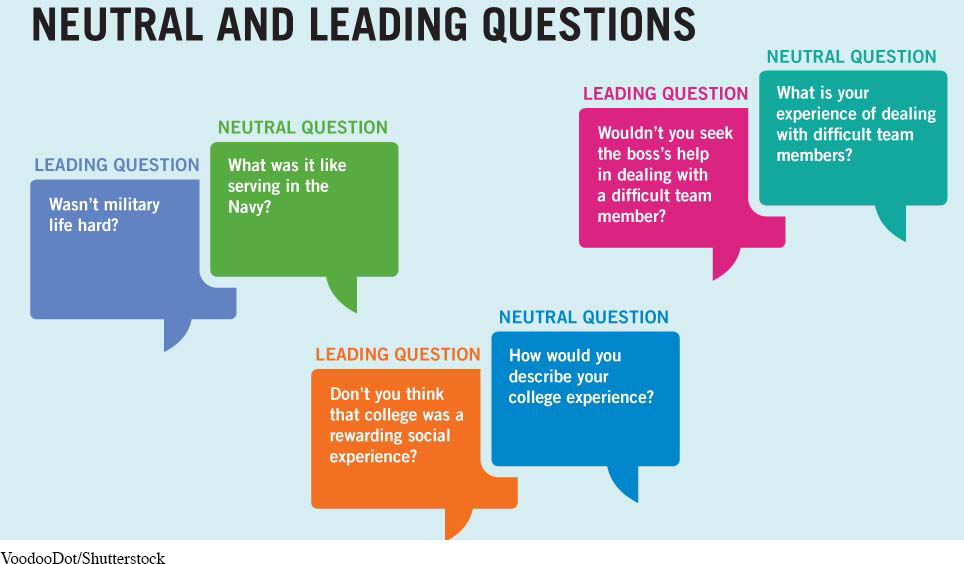

To find out what the interviewee really thinks or feels about a topic, you can use neutral questions (“What do you think of the new bonus policy?”). Leading questions point the respondent to an answer you prefer (“Don’t you think the new bonus policy is a great idea?”). For that reason, leading questions are generally less useful for finding out what an interviewee really thinks. Table A.2 provides examples of neutral and leading questions.

Knowing the different types of questions also helps when you’re being interviewed. For example, you will want to provide an appropriate level of detail, including examples, when responding to an open question. On the other hand, the interviewer may not expect you to provide a long response to a closed question, like, “Do you have a driver’s license?” As we discuss in the next section, listening carefully to the type of question being asked is important for providing satisfactory answers.