Identifying Your Main Points

The main points of your speech are the key statements or principles that support your speech thesis and help your audience understand your message. These are the ideas that build the case for why your thesis statement is true.

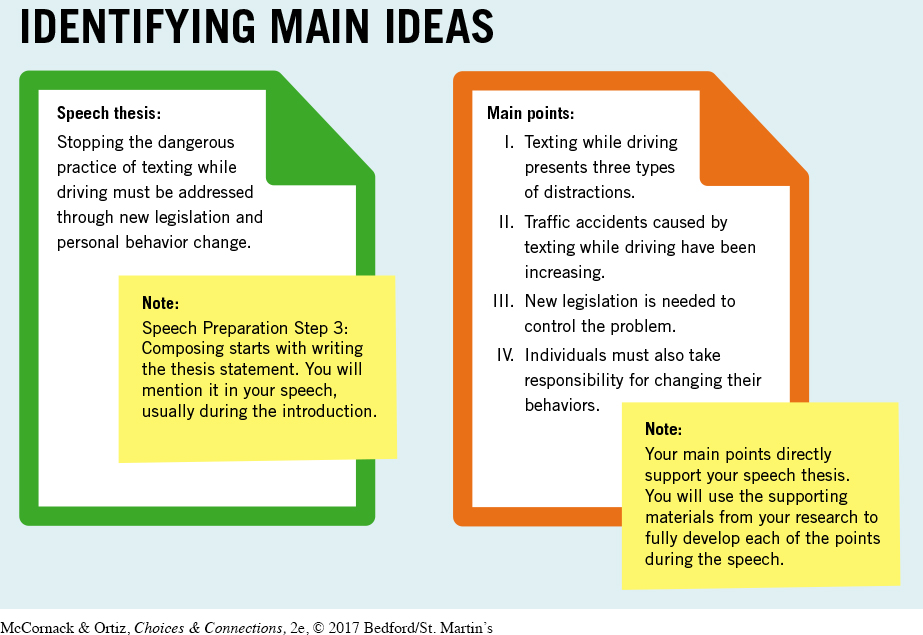

One way to identify your main points is to ask yourself what essential information is necessary to support your thesis. For example, if you were composing a speech about the dangers of texting while driving, your audience might need to understand why that behavior is dangerous. Let’s say that your research uncovered information about the different types of distractions caused by texting. These distractions could make up the first main point of your speech.

You also can identify main points for your thesis by looking for themes in your research. Suppose you have information from your state’s department of public safety showing that texting-

Additionally, you might discover that there are several general ideas that will support your thesis. However, you’ll only want to include those that are relevant to your audience. If your audience analysis (see Chapter 13, pp. 327–331) shows that your listeners are unaware of proposed laws to curb texting while driving, you might decide it is important to explain them in detail. This could also lead you to conclude that the audience could benefit from information about how to change their personal behavior and encourage others to do the same. These two final main points are important because they have a direct bearing on the audience. Table 14.2 reviews how the speech thesis and main points work together.

When developing main points, remember these guidelines:

A speech should contain a small number of main points, usually two to five. You want to keep your information manageable, making it easier for listeners to digest your speech.

Each main point must support your thesis statement. You don’t want to distract from your speech thesis by including a point that is unrelated to it. A focused presentation increases your chances of keeping the audience’s attention.

Each main point should focus on only one idea. If a point introduces a new idea, then it should appear as a separate main point. As an example, consider how many main points are included in the following sentence: Texting while driving presents three types of distractions, and you can take steps to stop the practice. (The answer is two; each idea—

types of distractions and steps to stop the practice— should be developed as a separate main point.)

Finally, some main points may need to be further divided into subpoints, specific principles derived from breaking down main points. Subpoints are especially useful if a particular main point can be broken down into parts or steps. For example, main point I in Table 14.2 could have three subpoints:

Texting while driving presents three types of distractions.2

Visual distraction

Manual distraction

Cognitive distraction

By using subpoints, you can explain a main point better, and your audience will have an easier time listening to the overall idea. When creating subpoints, make sure they all relate to the main point to avoid confusing your audience.