Power Distance

The degree to which people in a particular culture view the unequal distribution of power as acceptable is known as power distance (Hofstede, 1991, 2001). In high-power-distance cultures, it’s considered normal and even desirable for people of different social and professional status to have different levels of power (Ting-Toomey, 2005). In such cultures, people give privileged treatment and extreme respect to those in high-status positions (Ting-Toomey, 1999). They also expect individuals of lesser status to behave humbly, especially around people of higher status, who are expected to act superior.

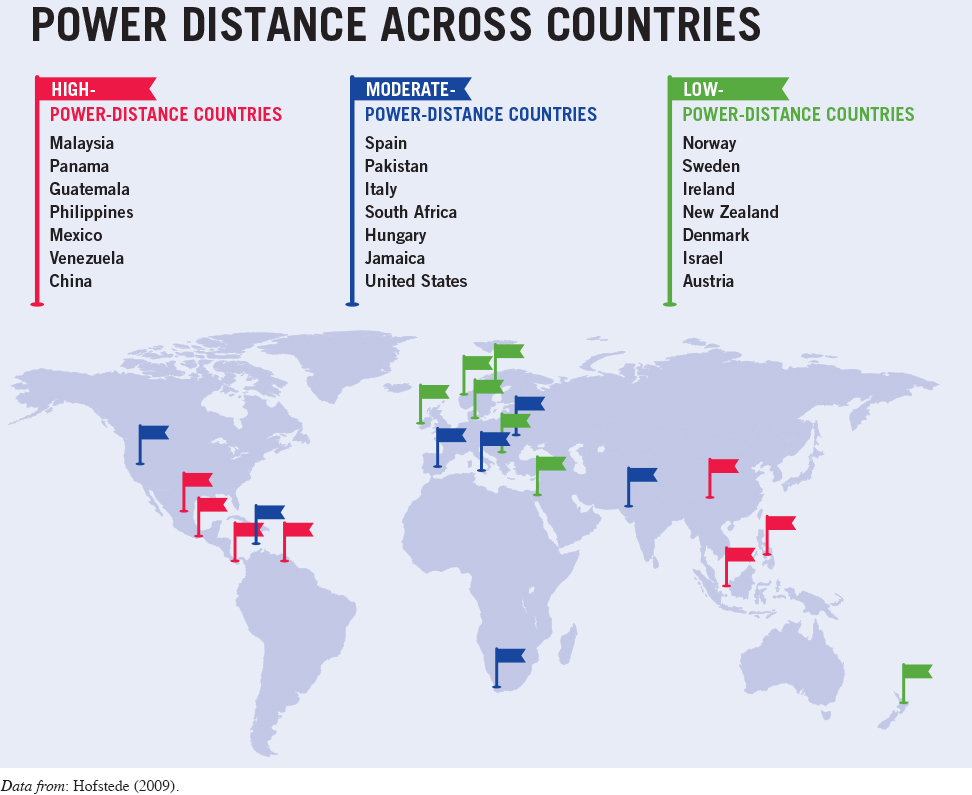

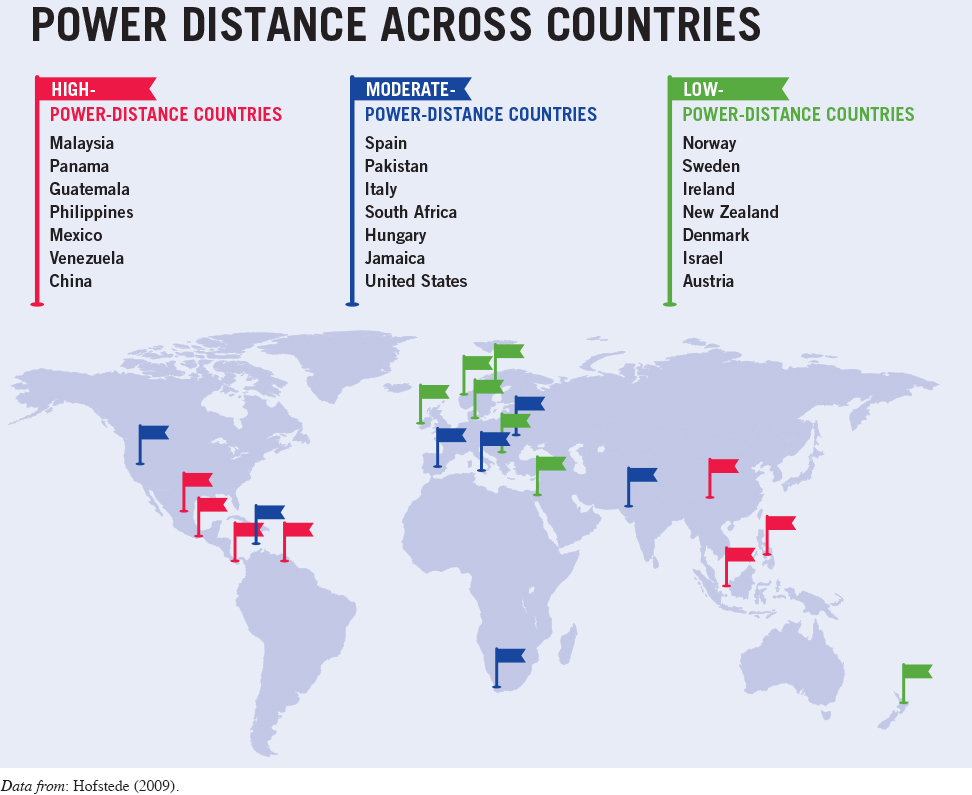

In low-power-distance cultures, people in high-status positions try to minimize the differences between themselves and lower-status persons by interacting with them in informal ways and treating them as equals (Oetzel et al., 2001). For instance, a high-level marketing executive might chat with the cleaning service workers in her office and invite them to join her for a coffee break. See Figure 4.2 for examples of high- and low-power-distance cultures.

Figure 4.2: FIGURE 4.2 POWER DISTANCE ACROSS COUNTRIES

Data from: Hofstede (2009)

Power distance affects how people deal with conflict. In low-power-distance cultures, people with little power may choose to engage in conflict with high-power people. What’s more, they may do so competitively: confronting high-power people and demanding that their goals be met. For instance, employees may question management decisions and suggest that alternatives be considered, or townspeople may attend a meeting and demand that the mayor address their concerns. These behaviors are much less common in high-power-distance cultures (Bochner & Hesketh, 1994), where low-power people are more likely to either avoid conflict with high-power people or accommodate them by giving in to their desires. Chapter 8 discusses more ways people approach conflict and how power affects those choices.

Power distance also influences how people communicate in close relationships, especially families. In traditional Mexican culture, for instance, the value of respeto (respect) emphasizes power distance between younger people and their elders (Delgado-Gaitan, 1993). As part of respeto, children are expected to defer to elders’ authority and to avoid openly disagreeing with them. In contrast, many Euro-Americans believe that once children reach adulthood, power in family relationships should be balanced—with children and their elders treating each other as equals (Kagawa & McCornack, 2004). To learn how you can handle cultural factors like power distance in group settings, see How to Communicate: Adapting to Cultural Differences on pages 104–105.