Ingroups and Outgroups

Culture has an enormous and powerful effect on your perceptions. When you grow up with certain cultural or co-

DOUBLE TAKE

INGROUPS  OUTGROUPS

OUTGROUPS

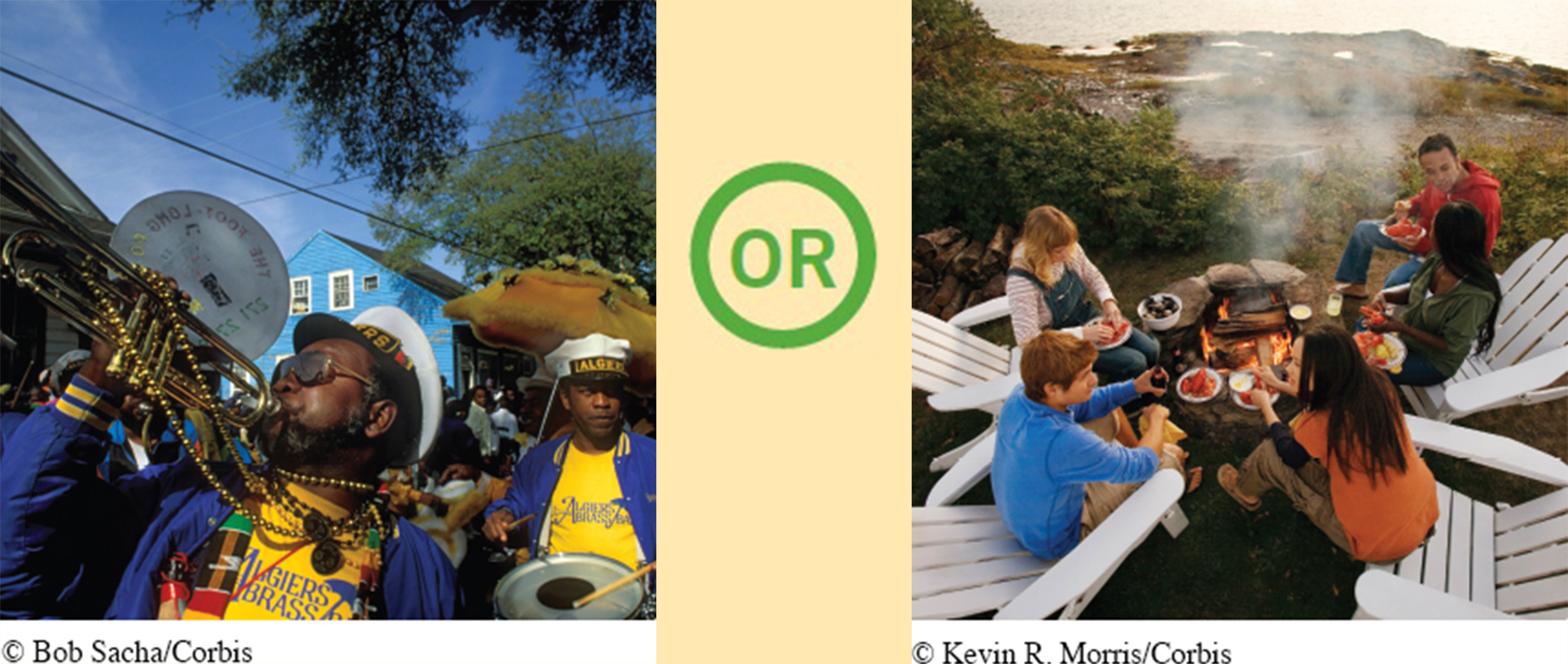

Would you classify the people and activities shown below as ingroupers or outgroupers? What specific aspects in each image make someone seem similar or dissimilar to you? How does this classification influence your communication?

People often feel passionately connected to their ingroups, especially when they reflect central aspects of their self-

You’re also more likely to form positive impressions of people you perceive as ingroupers (Giannakakis & Fritsche, 2011). For instance, in one study of 30 ethnic groups in East Africa, members of each group perceived ingroupers’ communication as more trustworthy, friendly, and honest than outgroupers’ communication (Brewer & Campbell, 1976). When people communicate in rude or inappropriate ways, you’re more inclined to form negative impressions of them if you see them as outgroupers (Brewer, 1999). If a customer at your job snaps at you but is wearing a T-

One of the strongest determinants of ingroup and outgroup perceptions is race. Race classifies people based on common ancestry or descent and is judged almost exclusively by a person’s physical features (Lustig & Koester, 2006). Perceiving someone’s race almost always means assigning him or her to ingrouper or outgrouper status (Brewer, 1999) and communicating with that person based on that status.

When categorizing other people as ingroupers or outgroupers, it’s easy to make mistakes. Even if a person seems to be the same race as you (e.g., white), she may have a very different ethnic, religious, and cultural heritage (you’re Irish Catholic; she’s Russian Jewish). Likewise, even if someone dresses differently than you do, he might hold cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values that are very similar to your own. If you assume that people are ingroupers or outgroupers based on surface-