Rhetorical Analysis of Visual Texts

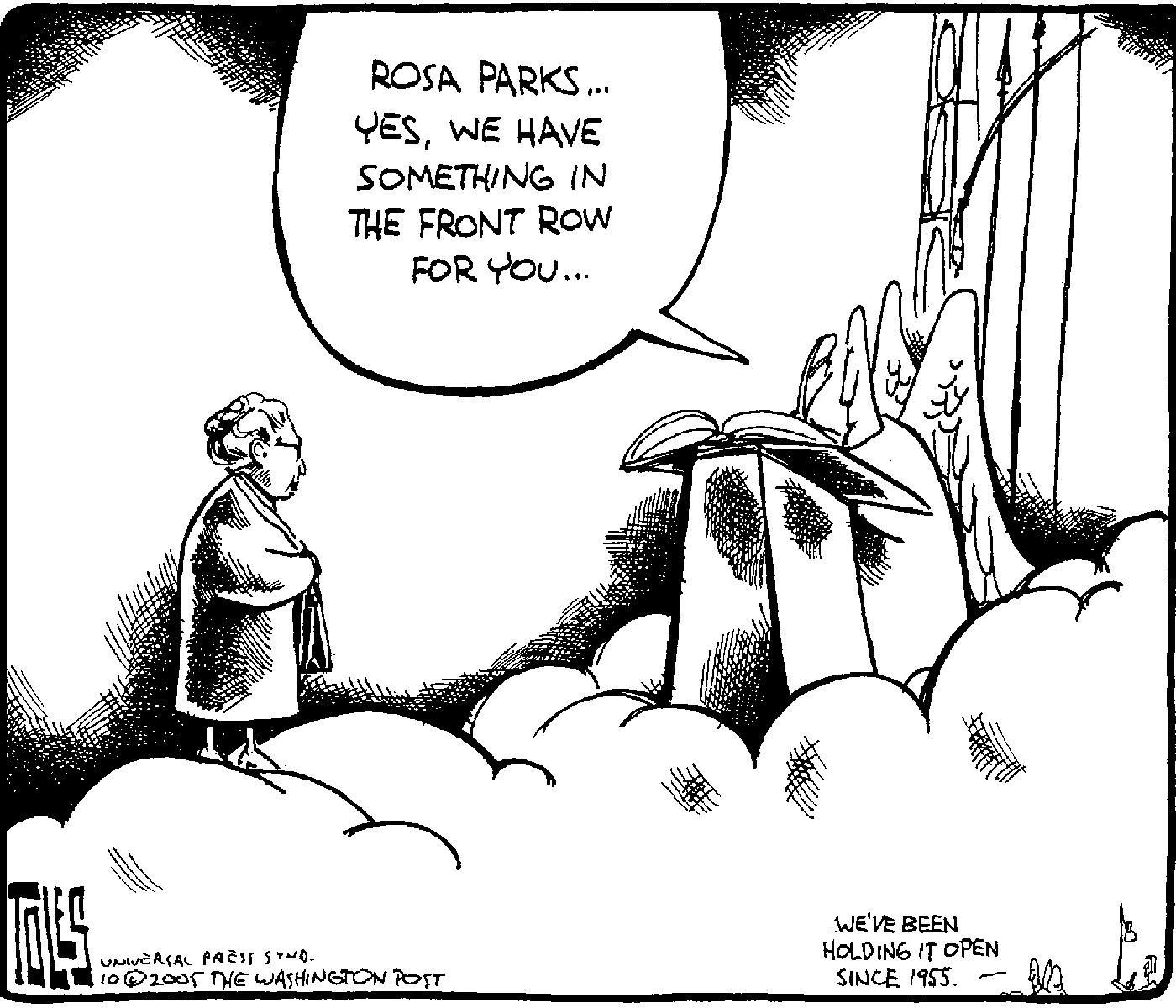

Printed Pages 25-26Many visual texts are full-fledged arguments. Although they may not be written in paragraphs or have a traditional thesis, they are occasioned by specific circumstances, they have a purpose (whether it is to comment on a current event or simply to urge you to buy something), and they make a claim and support it with appeals to authority, emotion, and reason. Consider the cartoon below, which cartoonist Tom Toles drew after the death of civil-rights icon Rosa Parks in 2005. Parks was the woman who in 1955 refused to give up her seat on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama; that act came to symbolize the struggle for racial equality in the United States.

We can discuss the cartoon rhetorically, just as we’ve been examining texts that are exclusively verbal: The occasion is the death of Rosa Parks. The speaker is Tom Toles, a respected and award-winning political cartoonist. The audience is made up of readers of the Washington Post and other newspapers—that is, it’s a very broad audience. The speaker can assume that his audience shares his admiration and respect for Parks and that they view her passing as the loss of a public figure as well as a private woman. Finally, the context is a memorial for a well-loved civil-rights activist, and Toles’s purpose is to remember Parks as an ordinary citizen whose courage and determination brought extraordinary results. The subject is the legacy of Rosa Parks, a well-known person loved by many.

Readers’ familiarity with Toles—along with his obvious respect for his subject—establishes his ethos. The image in the cartoon appeals primarily to pathos. Toles shows Rosa Parks, who was a devout Christian, as she is about to enter heaven through the pearly gates; they are attended by an angel, probably Saint Peter, who is reading a ledger. Toles depicts Parks wearing a simple coat and carrying her pocketbook, as she did while sitting on the bus so many years ago. Her features are somewhat detailed and realistic, making her stand out despite her modest posture and demeanor.

The commentary at the bottom right reads, “We’ve been holding it [the front row in heaven] open since 1955,” a reminder that more than fifty years have elapsed since Parks resolutely sat where she pleased. The caption can be seen as an appeal to both pathos and logos. Its emotional appeal is its acknowledgment that, of course, heaven would have been waiting for this good woman; but the mention of “the front row” appeals to logic because Parks made her mark in history for refusing to sit in the back of the bus. Some readers might even interpret the caption as a criticism of how slow the country was both to integrate and to pay tribute to Parks.