CULMINATING ACTIVITY The Apollo 11 Mission

Printed Pages 34-40● CULMINATING ACTIVITY ●

By this point, you have analyzed what we mean by the rhetorical situation, and you have learned a number of key concepts and terms. It’s time to put all the ideas together to examine a series of texts on a single subject. Following are five texts related to the 1969 Apollo 11 mission that landed the first humans on the moon. The first is a news article from the Times of London reporting the event; it is followed by a poem by Archibald MacLeish; next is a speech by William Safire that President Nixon would have given had the mission not been successful; the fourth is a commentary by novelist Ayn Rand; last is a political cartoon that appeared around the time. Discuss the purpose of each text and how the interaction among speaker, audience, and subject affects the text. How does each text appeal to ethos, pathos, and logos? Finally, how effective is each text in achieving its purpose?

Man Takes First Steps on the Moon

The Times

The following article appeared in a special 5 a.m. edition of the Times of London on July 21, 1969.

Neil Armstrong became the first man to take a walk on the moon’s surface early today. The spectacular moment came after he had inched his way down the ladder of the fragile lunar bug Eagle while colleague Edwin Aldrin watched his movements from inside the craft. The landing, in the Sea of Tranquillity, was near perfect and the two astronauts on board Eagle reported that it had not tilted too far to prevent a take-off. The first word from man on the moon came from Aldrin: “Tranquillity base. The Eagle has landed.” Of the first view of the lunar surface, he said: “There are quite a few rocks and boulders in the near area which are going to have some interesting colours in them.” Armstrong said both of them were in good shape and there was no need to worry about them. They had experienced no difficulty in manoeuvring the module in the moon’s gravity. There were tense moments in the mission control centre at Houston while they awaited news of the safe landing. When it was confirmed, one ground controller was heard to say: “We got a bunch of guys on the ground about to turn blue. We’re breathing again.” Ten minutes after landing, Aldrin radioed: “We’ll get to the details of what’s around here. But it looks like a collection of every variety, shape, angularity, granularity; a collection of just about every kind of rock.” He added: “The colour depends on what angle you’re looking at…rocks and boulders look as though they’re going to have some interesting colours.”

Armstrong says: one giant leap for mankind

From the News Team in Houston and London

It was 3.56 a.m. (British Standard Time) when Armstrong stepped off the ladder from Eagle and on to the moon’s surface. The module’s hatch had opened at 3.39 a.m.

“That’s one small step for man but one giant leap for mankind,” he said as he stepped on the lunar surface.

The two astronauts opened the hatch of their lunar module at 3.39 a.m. in preparation for Neil Armstrong’s walk. They were obviously being ultra careful over the operation for there was a considerable time lapse before Armstrong moved backwards out of the hatch to start his descent down the ladder.

5

Aldrin had to direct Armstrong out of the hatch because he was walking backwards and could not see the ladder.

Armstrong moved on to the porch outside Eagle and prepared to switch the television cameras which showed the world his dramatic descent as he began to inch his way down the ladder.

By this time the two astronauts had spent 25 minutes of their breathing time but their oxygen packs on their backs last four hours.

When the television cameras switched on there was a spectacular shot of Armstrong as he moved down the ladder. Viewers had a clear view as they saw him stepping foot by foot down the ladder, which has nine rungs.

He reported that the lunar surface was a “very fine-grained powder.”

10

Clutching the ladder Armstrong put his left foot on the lunar surface and reported it was like powdered charcoal and he could see his footprints on the surface. He said the L.E.M.’s engine had left a crater about a foot deep but they were “on a very level place here.”

Standing directly in the shadow of the lunar module Armstrong said he could see very clearly. The light was sufficiently bright for everything to be clearly visible.

The next step was for Aldrin to lower a hand camera down to Armstrong. This was the camera which Armstrong was to use to film Aldrin when he descends from Eagle.

Armstrong then spent the next few minutes taking photographs of the area in which he was standing and then prepared to take the “contingency” sample of lunar soil.

This was one of the first steps in case the astronauts had to make an emergency take-off before they could complete the whole of their activities on the moon.

15

Armstrong said: “It is very pretty out here.”

Using the scoop to pick up the sample Armstrong said he had pushed six to eight inches into the surface. He then reported to the mission control centre that he placed the sample lunar soil in his pocket.

The first sample was in his pocket at 4.08 a.m. He said the moon “has soft beauty all its own,” like some desert of the United States….

Greatest moment of time

President Nixon, watching the events on television, described it as “one of the greatest moments of our time.” He told Mr. Ron Ziegler, the White House press secretary, that the last 22 seconds of the descent were the longest he had ever lived through.

Mr. Harold Wilson, in a television statement, expressed “our deep wish for a safe return at the end of what has been a most historic scientific achievement in the history of man.” The Prime Minister, speaking from 10 Downing Street, said: “The first feeling of all in Britain is that this very dangerous part of the mission has been safely accomplished.”

20

Moscow Radio announced the news solemnly as the main item in its 11.30 news broadcast. There was no immediate news of Luna 15.

At Castelgandolfo the Pope greeted news of the lunar landing by exclaiming: “Glory to God in the highest and peace on earth to men of good will!”

In an unscheduled speech from his summer residence the Pope, who followed the flight on colour television, said: “We, humble representatives of that Christ, who, coming among us from the abyss of divinity, has made to resound in the heavens this blessed voice, today we make an echo, repeating it in a celebration on the part of the whole terrestrial globe, with no more unsurpassable bounds of human existence, but openness to the expanse of endless space and a new destiny.”

“Glory to God!” President Saragat of Italy said in a statement: “May this victory be a good omen for an even greater victory: the definite conquest of peace, of justice, of liberty, for all peoples of the World.”

President Charles Helou of Lebanon followed the flight and landing with special dispatches from the Information Ministry. A spokesman said he would send an official message later.

25

In Jordan King Husain sent a congratulatory message to the astronauts and President Nixon.

In Stockholm Mr. Tage Erlander, the Swedish Prime Minister, said he planned to cable President Nixon his congratulations as soon as the astronauts returned to Earth. King Gustav Adolf was watching television at touchdown time and told friends he was “thrilled” by the Apollo performance.

In Cuba the national radio announced the moon landing 12 minutes after it was accomplished.

Sir Bernard Lovell, Director of the Jodrell Bank observatory, said: “The moment of touchdown was one of the moments of greatest drama in the history of man. The success in this part of the enterprize opens the most enormous opportunities for the future exploration of the universe.”

(1969)

Voyage to the Moon

Archibald Macleish

The following poem by Archibald MacLeish, who had been Librarian of Congress during World War II, appeared in the New York Times on July 21, 1969, the morning after the moon landing.

Presence among us,

wanderer in our skies,

dazzle of silver in our leaves and on our

waters silver.

5

O

silver evasion in our farthest thought—

“the visiting moon”…“the glimpses of the moon”…

and we have touched you!

From the first of time,

10

before the first of time, before the

first men tasted time, we thought of you.

You were a wonder to us, unattainable,

a longing past the reach of longing,

a light beyond our light, our lives—perhaps

15

a meaning to us…

Now

our hands have touched you in your depth of night.

Three days and three nights we journeyed,

steered by farthest stars, climbed outward,

20

crossed the invisible tide-rip where the floating dust

falls one way or the other in the void between,

followed that other down, encountered

cold, faced death—unfathomable emptiness…

Then, the fourth day evening, we descended,

25

made fast, set foot at dawn upon your beaches,

sifted between our fingers your cold sand.

We stand here in the dusk, the cold, the silence…

and here, as at the first of time, we lift our heads.

Over us, more beautiful than the moon, a

30

moon, a wonder to us, unattainable,

a longing past the reach of longing,

a light beyond our light, our lives—perhaps

a meaning to us…

O, a meaning!

35

over us on these silent beaches the bright

earth,

presence among us

(1969)

In Event of Moon Disaster

William Safire

The following speech, revealed in 1999, was prepared by President Nixon’s speechwriter, William Safire, to be used in the event of a disaster that would maroon the astronauts on the moon.

Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.

These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice. These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.

They will be mourned by their families and friends; they will be mourned by their nation; they will be mourned by the people of the world; they will be mourned by a Mother Earth that dared send two of her sons into the unknown.

In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.

5

In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.

Others will follow, and surely find their way home. Man’s search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts. For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.

(1969)

The July 16, 1969, Launch: A Symbol of Man’s Greatness

Ayn Rand

The following commentary by novelist Ayn Rand first appeared in the Objectivist, a publication created by Rand and others to put forward their philosophy of objectivism, which values individualism, freedom, and reason.

“No matter what discomforts and expenses you had to bear to come here,” said a NASA guide to a group of guests, at the conclusion of a tour of the Space Center on Cape Kennedy, on July 15, 1969, “there will be seven minutes tomorrow morning that will make you feel it was worth it.”

It was.

[The launch] began with a large patch of bright, yellow-orange flame shooting sideways from under the base of the rocket. It looked like a normal kind of flame and I felt an instant’s shock of anxiety, as if this were a building on fire. In the next instant the flame and the rocket were hidden by such a sweep of dark red fire that the anxiety vanished: this was not part of any normal experience and could not be integrated with anything. The dark red fire parted into two gigantic wings, as if a hydrant were shooting streams of fire outward and up, toward the zenith—and between the two wings, against a pitch-black sky, the rocket rose slowly, so slowly that it seemed to hang still in the air, a pale cylinder with a blinding oval of white light at the bottom, like an upturned candle with its flame directed at the earth. Then I became aware that this was happening in total silence, because I heard the cries of birds winging frantically away from the flames. The rocket was rising faster, slanting a little, its tense white flame leaving a long, thin spiral of bluish smoke behind it. It had risen into the open blue sky, and the dark red fire had turned into enormous billows of brown smoke, when the sound reached us: it was a long, violent crack, not a rolling sound, but specifically a cracking, grinding sound, as if space were breaking apart, but it seemed irrelevant and unimportant, because it was a sound from the past and the rocket was long since speeding safely out of its reach—though it was strange to realize that only a few seconds had passed. I found myself waving to the rocket involuntarily, I heard people applauding and joined them, grasping our common motive; it was impossible to watch passively, one had to express, by some physical action, a feeling that was not triumph, but more: the feeling that that white object’s unobstructed streak of motion was the only thing that mattered in the universe.

What we had seen, in naked essentials—but in reality, not in a work of art—was the concretized abstraction of man’s greatness.

5

The fundamental significance of Apollo 11’s triumph is not political; it is philosophical; specifically, moral-epistemological.1

The meaning of the sight lay in the fact that when those dark red wings of fire flared open, one knew that one was not looking at a normal occurrence, but at a cataclysm which, if unleashed by nature, would have wiped man out of existence—and one knew also that this cataclysm was planned, unleashed, and controlled by man, that this unimaginable power was ruled by his power and, obediently serving his purpose, was making way for a slender, rising craft. One knew that this spectacle was not the product of inanimate nature, like some aurora borealis, or of chance, or of luck, that it was unmistakably human—with “human,” for once, meaning grandeur—that a purpose and a long, sustained, disciplined effort had gone to achieve this series of moments, and that man was succeeding, succeeding, succeeding! For once, if only for seven minutes, the worst among those who saw it had to feel—not “How small is man by the side of the Grand Canyon!”—but “How great is man and how safe is nature when he conquers it!”

That we had seen a demonstration of man at his best, no one could doubt—this was the cause of the event’s attraction and of the stunned numbed state in which it left us. And no one could doubt that we had seen an achievement of man in his capacity as a rational being—an achievement of reason, of logic, of mathematics, of total dedication to the absolutism of reality.

Frustration is the leitmotif in the lives of most men, particularly today—the frustration of inarticulate desires, with no knowledge of the means to achieve them. In the sight and hearing of a crumbling world, Apollo 11 enacted the story of an audacious purpose, its execution, its triumph, and the means that achieved it—the story and the demonstration of man’s highest potential.

(1969)

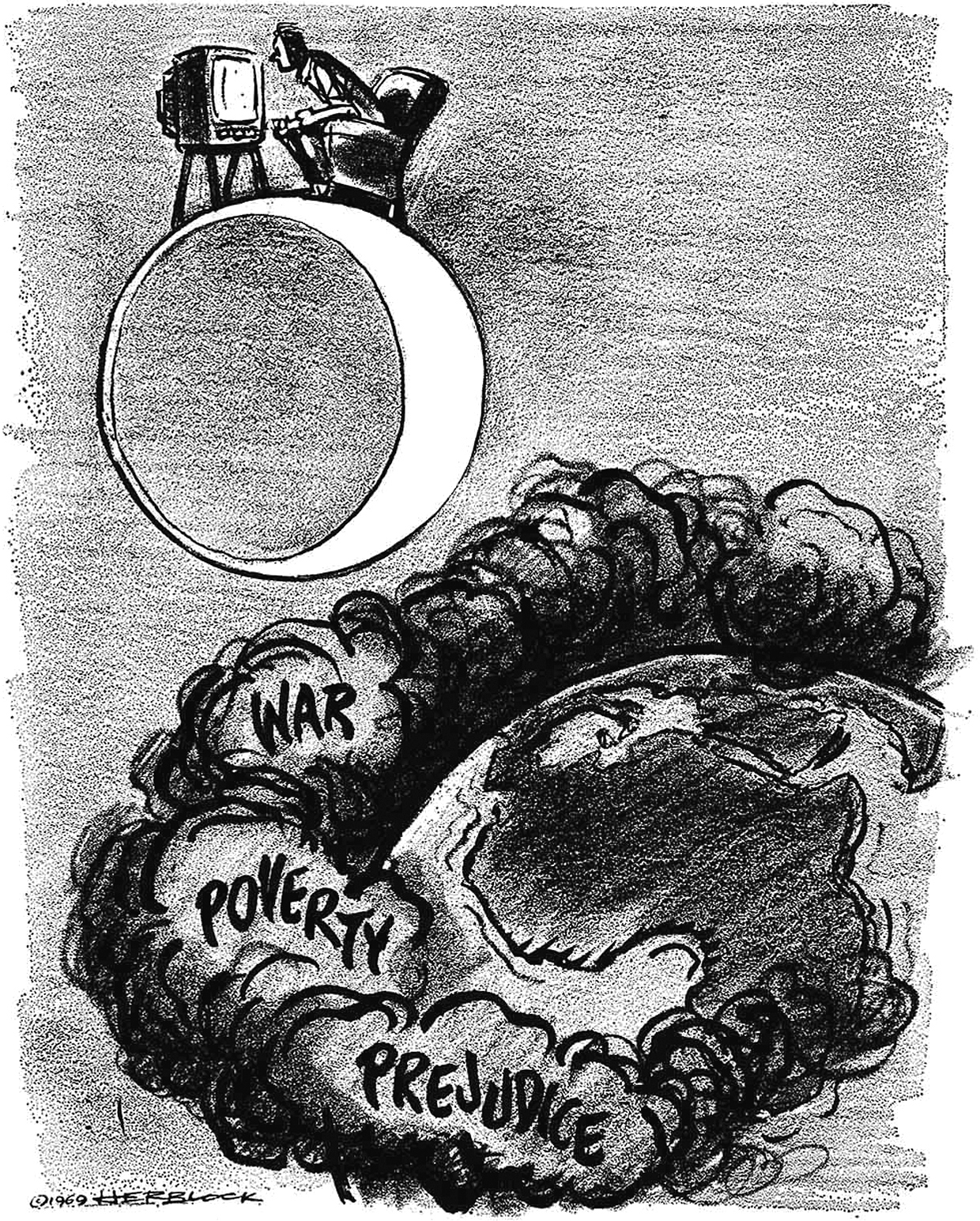

Transported

Herblock

The following editorial cartoon by the famous cartoonist Herb Block, or Herblock, appeared in the Washington Post on July 18, 1969.