What Is Argument?

Printed Pages 85-89Although we have been discussing argument in previous chapters, the focus has been primarily on rhetorical appeals and style. We’ll continue examining those elements, but here we take a closer look at an argument’s claim, evidence, and organization.

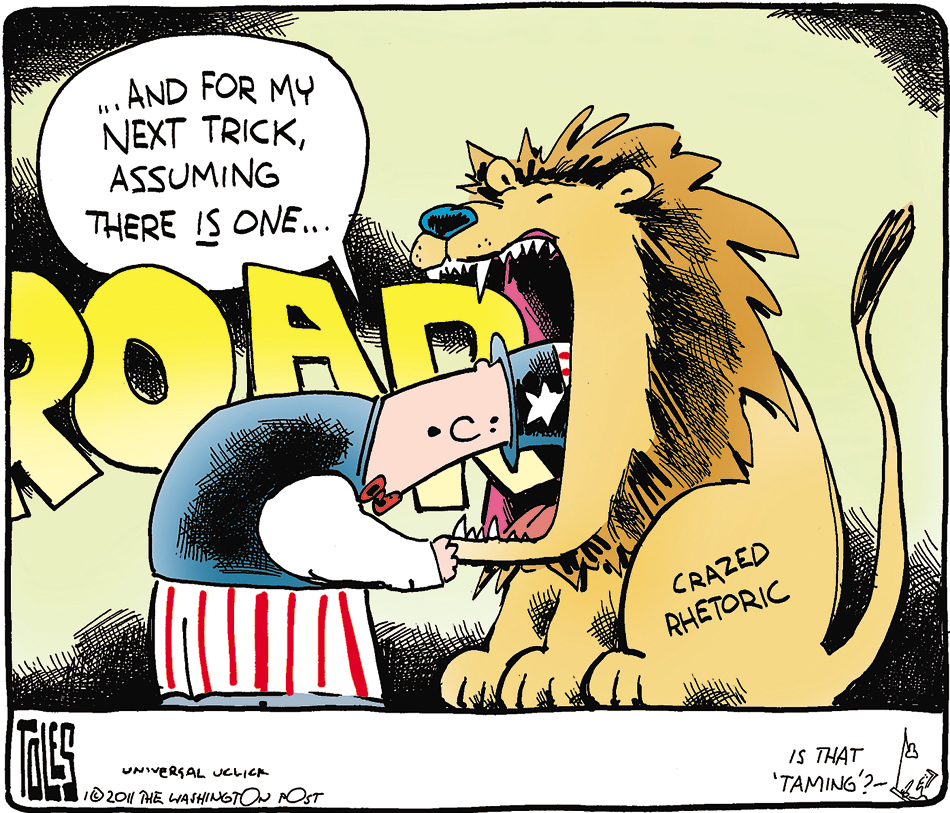

Let’s start with some definitions. What is argument? Is it a conflict? A contest between opposing forces to prove the other side wrong? A battle with words? Or is it, rather, a process of reasoned inquiry and rational discourse seeking common ground? If it is the last one, then we engage in argument whenever we explore ideas rationally and think clearly about the world. Yet these days argument is often no more than raised voices interrupting one another, exaggerated assertions without adequate support, and scanty evidence from sources that lack credibility. We might call this “crazed rhetoric,” as political commentator Tom Toles does in the cartoon on the following page.

This cartoon appeared on January 16, 2011, a few days after Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords became the victim of a shooting; six people were killed and another thirteen injured. Many people saw this tragedy as stemming from vitriolic political discourse that included violent language. Toles argues that Uncle Sam, and thus the country, is in danger of being devoured by “crazed rhetoric.” There may not be a “next trick” or a “taming,” he suggests, if the rhetorical lion continues to roar.

Is Toles’s view exaggerated? Whether you answer yes or no to that question, it seems quite clear that partisanship and polarization often hold sway over dialogue and civility when people think of argument. In our discussions, however, we define argument as a persuasive discourse, a coherent and considered movement from a claim to a conclusion. The goal of this chapter is to avoid thinking of argument as a zero-sum game of winners and losers but, instead, to see it as a means of better understanding other people’s ideas as well as your own.

In Chapter 1, we discussed concession and refutation as a way to acknowledge a counterargument, and we want to re-emphasize the usefulness of that approach. Viewing anyone who disagrees with you as an adversary makes it very likely that the conversation will escalate into an emotional clash, and treating opposing ideas disrespectfully rarely results in mutual understanding. Twentieth-century psychologist Carl Rogers stressed the importance of replacing confrontational argument tactics with ones that promote negotiation, compromise, and cooperation. Rogerian arguments are based on the assumption that having a full understanding of an opposing position is essential to responding to it persuasively and refuting it in a way that is accommodating rather than alienating. Ultimately, the goal of a Rogerian argument is not to destroy your opponents or dismantle their viewpoints but rather to reach a satisfactory compromise.

So what does a civil argument look like? Let’s examine a short article that appeared in Ode magazine in 2009 entitled “Why Investing in Fast Food May Be a Good Thing.” In this piece, Amy Domini, a financial advisor and leading voice for socially responsible investing, argues the counterintuitive position that investing in the fast-food industry can be an ethically responsible choice.

Why Investing in Fast Food May Be a Good Thing

Amy Domini

My friends and colleagues know I’ve been an advocate of the Slow Food movement for many years. Founded in Italy 20 years ago, Slow Food celebrates harvests from small-scale family farms, prepared slowly and lovingly with regard for the health and environment of diners. Slow Food seeks to preserve crop diversity, so the unique taste of “heirloom” apples, tomatoes and other foods don’t perish from the Earth. I wish everyone would choose to eat this way. The positive effects on the health of our bodies, our local economies and our planet would be incalculable. Why then do I find myself investing in fast-food companies?

The reason is social investing isn’t about investing in perfect companies. (Perfect companies, it turns out, don’t exist.) We seek to invest in companies that are moving in the right direction and listening to their critics. We offer a road map to bring those companies to the next level, step by step. No social standard causes us to reject restaurants, even fast-food ones, out of hand. Although we favor local, organic food, we recognize it isn’t available in every community, and is often priced above the means of the average household. Many of us live more than 100 miles from a working farm.

Fast food is a way of life. In America, the average person eats it more than 150 times a year. In 2007, sales for the 400 largest U.S.-based fast-food chains totaled $277 billion, up 7 percent from 2006.

Fast food is a global phenomenon. Major chains and their local competitors open restaurants in nearly every country. For instance, in Greece, burgers and pizza are supplanting the traditional healthy Mediterranean diet of fish, olive oil and vegetables. Doctors are treating Greek children for diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure—ailments rarely seen in the past.

5

The fast-food industry won’t go away anytime soon. But in the meantime, it can be changed. And because it’s so enormous, even seemingly modest changes can have a big impact. In 2006, New York City banned the use of trans-fats (a staple of fast food) in restaurants, and in 2008, California became the first state to do so. When McDonald’s moved to non-trans-fats for making French fries, the health benefits were widespread. Another area of concern is fast-food packaging, which causes forest destruction and creates a lot of waste. In the U.S. alone, 1.8 million tons of packaging is generated each year. Fast-food containers make up about 20 percent of litter, and packaging for drinks and snacks adds another 20 percent.

A North Carolina–based organization called the Dogwood Alliance has launched an effort to make fast-food companies reduce waste and source paper responsibly. Through a campaign called No Free Refills, the group is pressing fast-food companies to reduce their impact on the forests of the southern United States, the world’s largest paper-producing region. They’re pushing companies to:

- Reduce the overuse of packaging.

- Maximize use of 100 percent post-consumer recycled boxboard.

- Eliminate paper packaging from the most biologically important endangered forests.

- Eliminate paper packaging from suppliers that convert natural forests into industrial pine plantations.

- Encourage packaging suppliers to source fiber from responsibly managed forests certified by the Forest Stewardship Council.

- Recycle waste in restaurants to divert paper and other material from landfills.

Will the fast-food companies adopt all these measures overnight? No. But along with similar efforts worldwide, this movement signals that consumers and investors are becoming more conscious of steps they can take toward a better world—beginning with the way they eat.

While my heart will always be with Slow Food, I recognize the fast-food industry can improve and that some companies are ahead of others on that path.

(2009)

Domini begins by reminding her readers of her ethos as “an advocate of the Slow Food movement for many years.” By describing some of the goals and tenets of that movement, including the “positive effects” it can have, she establishes common ground before she discusses her position—one that the Slow Food advocates are not likely to embrace, at least not initially. In fact, instead of asserting her position in a strong declarative sentence, Domini asks a question that invites her audience to hear her explanation: “Why then do I find myself investing in fast-food companies?” (par. 1). She provides evidence that supports her choice to take that action: she uses statistics to show that slow food is not available in all communities, while fast food is an expanding industry. She uses the example of Greece to show that fast food is becoming a global phenomenon. She gives numerous examples of how fast-food companies are improving ingredients and reducing waste to illustrate how working to change fast-food practices can have a significant impact on public health and the environment. After presenting her viewpoint, Domini ends by acknowledging that her “heart will always be with Slow Food”; but that fact should not preclude her supporting those in the fast-food industry who are making socially and environmentally responsible decisions.