Claims of Value

Perhaps the most common type of claim is a claim of value, which argues that something is good or bad, right or wrong, desirable or undesirable. Of course, just like any other claim, a claim of value must be arguable. Claims of value may be personal judgments based on taste, or they may be more objective evaluations based on external criteria. For instance, if you argue that Ryan Gosling is the best leading man in Hollywood, that is simply a matter of taste. The criteria for what is “best” and what defines a “leading man” are strictly personal. Another person could argue that while Gosling might be the best-looking actor in Hollywood, Robert Downey Jr. is more highly paid and his movies tend to make more money. That is an evaluation based on external criteria—dollars and cents.

To develop an argument from a claim of value, you must establish specific criteria or standards and then show to what extent the subject meets your criteria. Amy Domini’s argument is largely one of value as she supports her claim that investing in fast-food companies can be a positive thing. The very title of Domini’s essay suggests a claim of value: “Why Investing in Fast Food May Be a Good Thing.” She develops her argument by explaining the impact that such investing can have on what food choices are available and what the impact of those choices is.

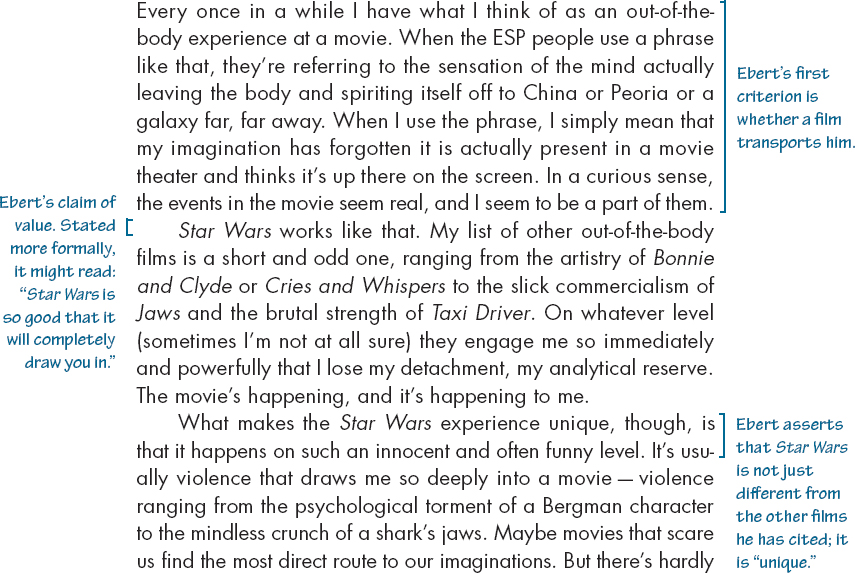

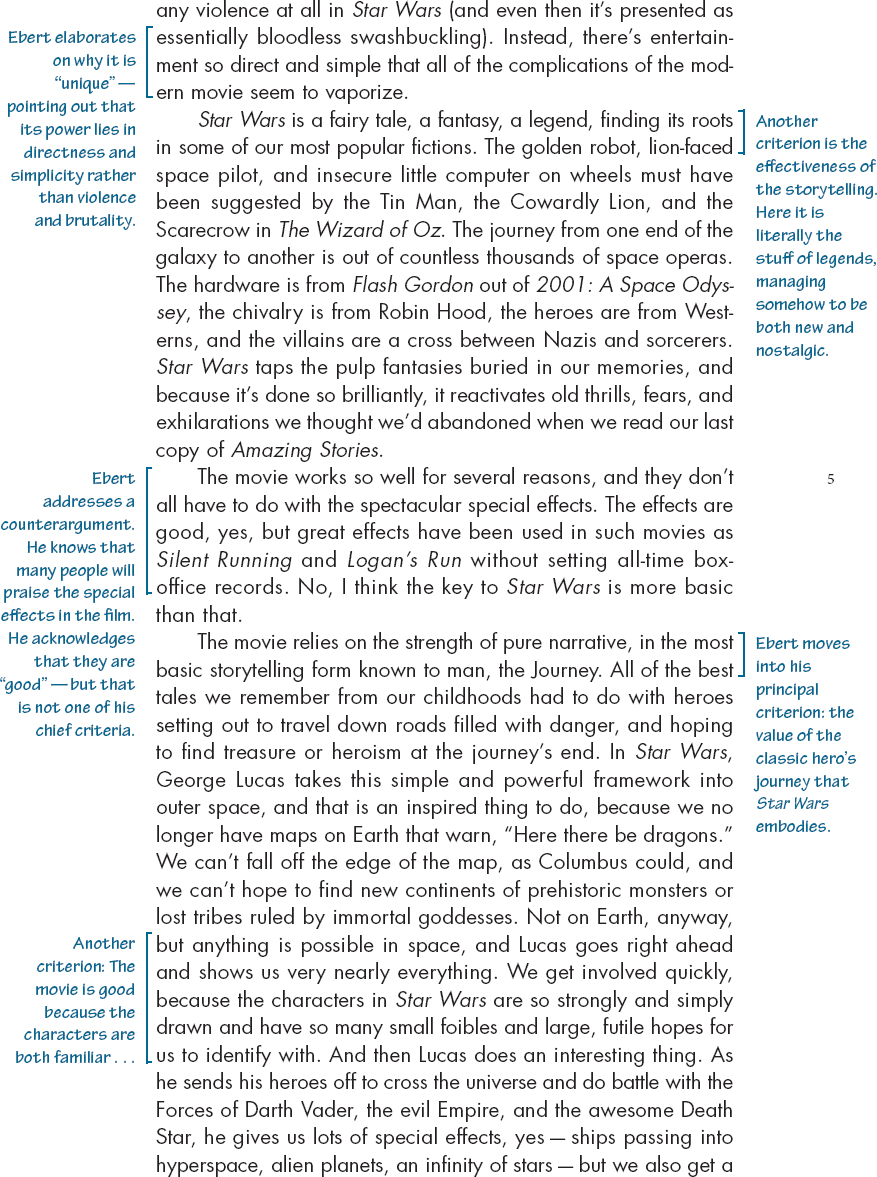

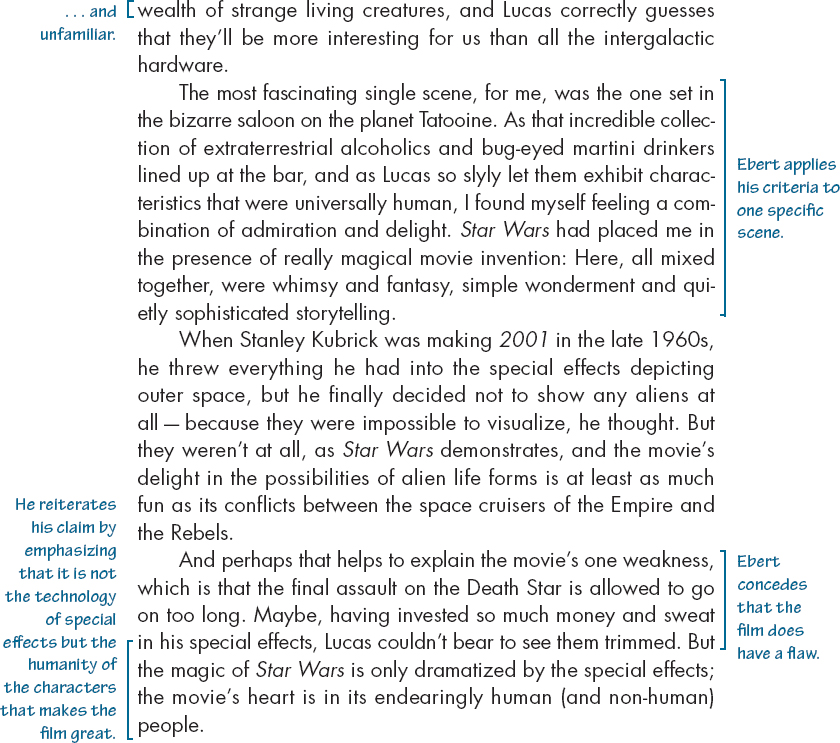

Entertainment reviews—of movies, television shows, concerts, books—are good examples of arguments developed from claims of value. Take a look at this one, movie critic Roger Ebert’s 1977 review of the first Star Wars movie. He raved. Notice how he states his four-star claim—it’s a great movie!—in several ways throughout the argument and sets up his criteria at each juncture.

Star Wars

Roger Ebert

(1977)