Chapter 5 A Meeting of Old and New Worlds: Beginnings to 1750

Printed Pages 187-192Beginnings to 1750

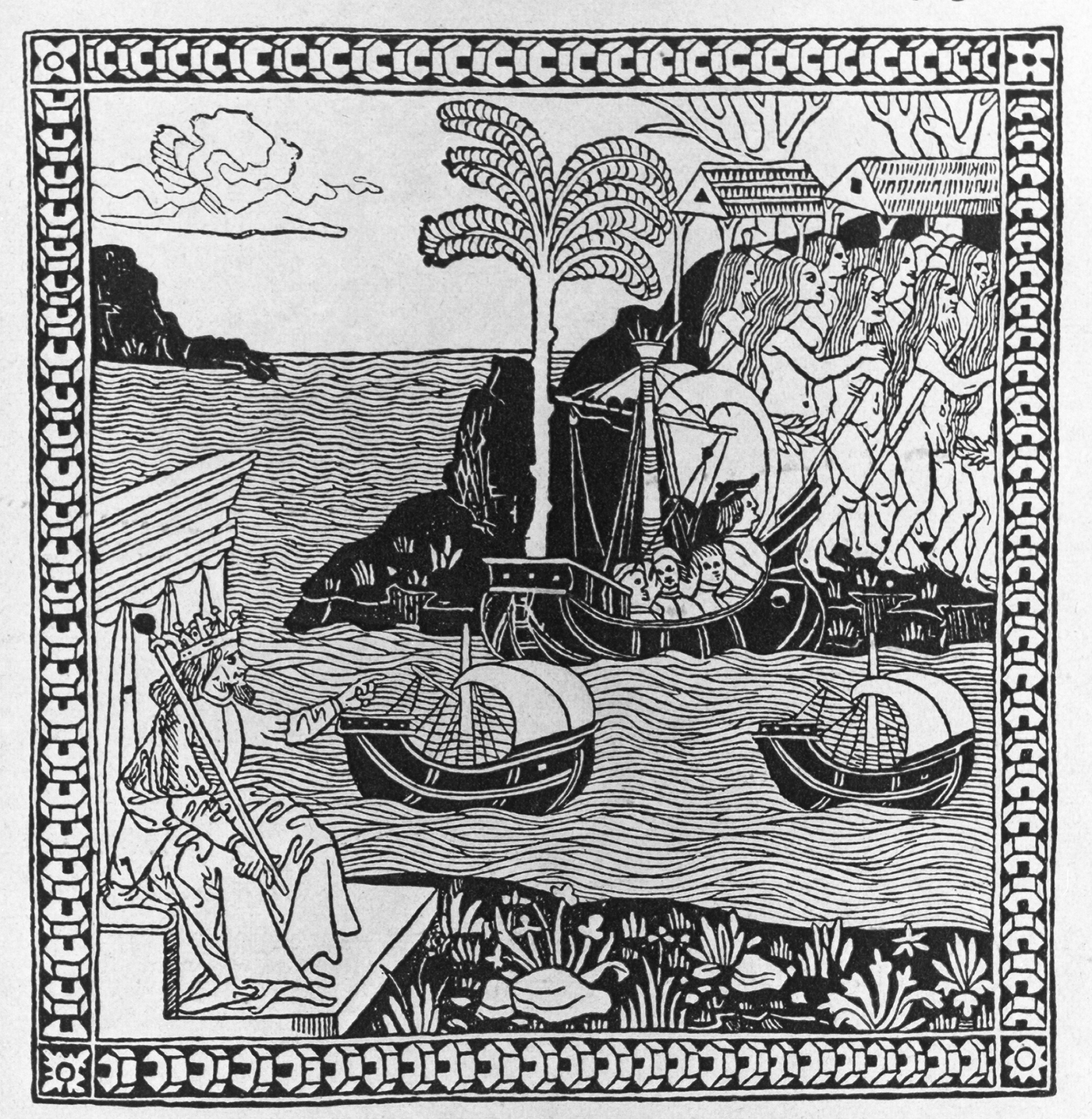

The philosopher George Santayana once said of Christopher Columbus, “He gave the world another world.” But the so-called New World was not really new at all. Humans have populated the continents of the Americas since as early as 30,000 b.c.e., so any date we choose as the starting point of our national body of literature is arbitrary; in fact, many of the pieces in this chapter were not written by “Americans” as we understand the term today, since neither the original inhabitants of the American continents nor the earliest European explorers and settlers considered themselves Americans. When Columbus landed in this new world, the land that became America was inhabited by an estimated 5 million natives, living in hundreds of tribes, many with rich traditions of myths and legends. “How the World Was Made” and “The Earth on Turtle’s Back” are two origin stories in this chapter that exemplify this oral tradition. Beyond the vibrant cultural life found in native tribes, many of them had developed sophisticated social structures. Perhaps the most impressive of these was the Iroquois Confederacy, an alliance of six nations governed by the Iroquois Constitution, a document so democratic in philosophy that Benjamin Franklin reportedly presented it as a model when the Founding Fathers began drafting the U.S. Constitution.

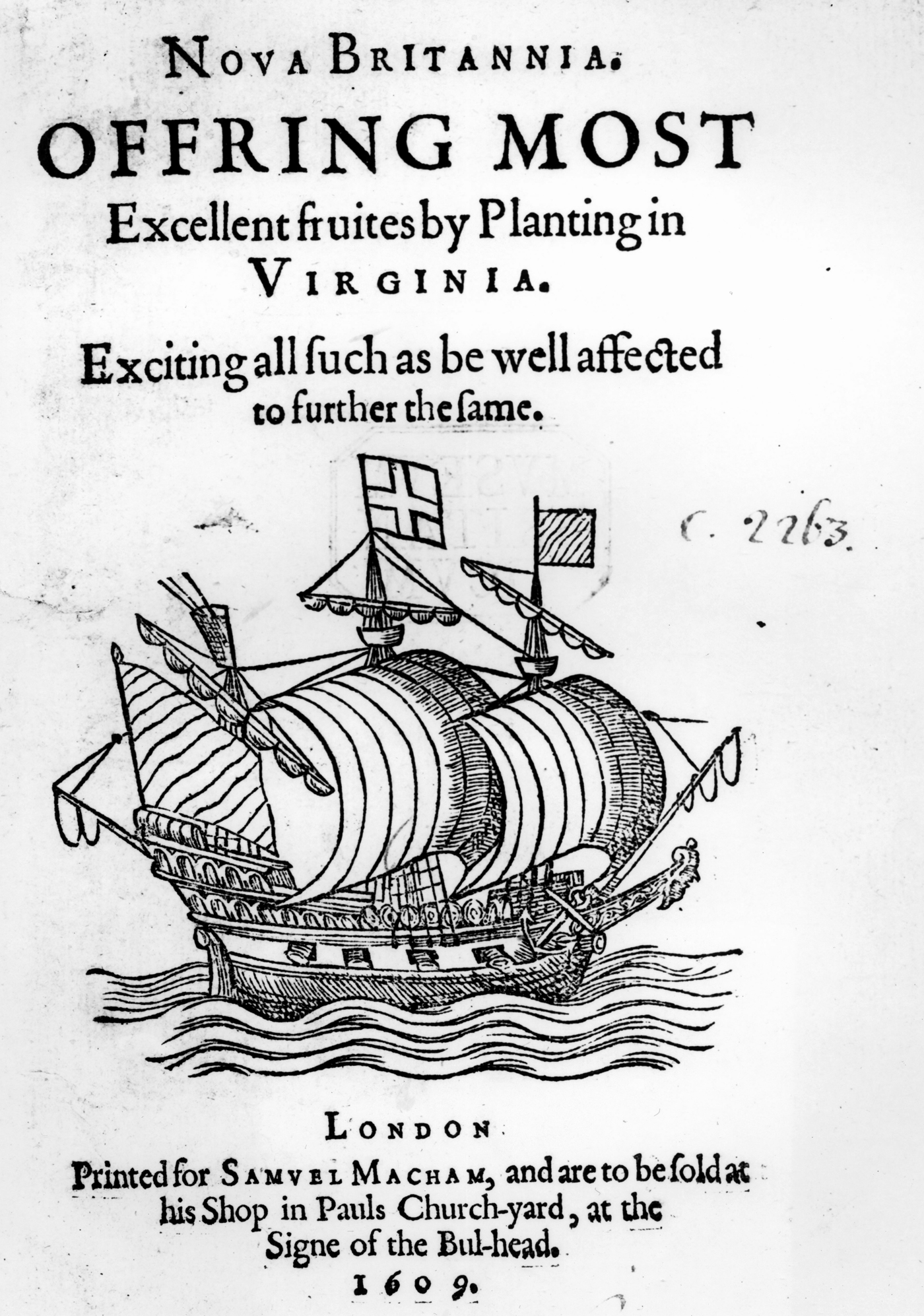

Many American schoolchildren learn that “in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” But Columbus never actually set foot on North America, nor was he the first European explorer to reach the American continents—Leif Eriksson led a Nordic expedition to Newfoundland in the eleventh century. Nevertheless, Columbus remains a key figure in America’s history and imagination. This chapter includes a group of texts considering his legacy, and the national holiday that bears his name. Columbus’s four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean galvanized Europe’s interest in and awareness of the American continent and initiated a period of fierce competition to colonize “the New World.” In the 150 years after Columbus first set sail, Amerigo Vespucci explored Brazil and the West Indies; John Cabot sought the Northwest Passage; Hernando de Soto charted the southern region of North America; Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, respectively, conquered the Aztecs and the Incas of South America; George Weymouth explored New England; Henry Hudson sailed the river that now bears his name; and the Pilgrims reached Plymouth Rock. From the fifteenth to the early eighteenth century, America was little more than a loose collection of settlements, some commissioned by European monarchs for economic and imperial purposes, some privately funded for farming and trading, and others composed of religious dissenters seeking refuge from discrimination in their native lands.

This heady period of discovery was also a time when cultures clashed violently. Waves of settlers brought with them disease and destruction that eradicated a large percentage of the indigenous population of the Americas. Acknowledgment of the damage done, respect for the cultures eradicated, and curiosity about the ways of life now lost have been relatively recent phenomena. One notable exception to this rule can be found in the writings of the Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca, whose account of his harrowing journey through the American south is a unique, and comparatively sympathetic, anthropological exploration of the native populations he encountered.

This chapter includes many pieces that explore the tension between Native Americans and white settlers. Most are told from the perspective of the colonists, chronicling the genuine dangers of colonial life. One such narrative by Mary Rowlandson, a colonist in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, tells her story of captivity by Native Americans in 1676 and her eventual ransom. When it was published in 1682, it became the first best seller of American literature. Another group of texts revolving around Pocahontas examines the divide between the real woman, who was a daughter of a Native American chief and who married a white settler, and the mythical icon of popular culture. The texts question why Pocahontas is still important to our culture, what she represents, and how she is and has been represented, both textually and graphically.

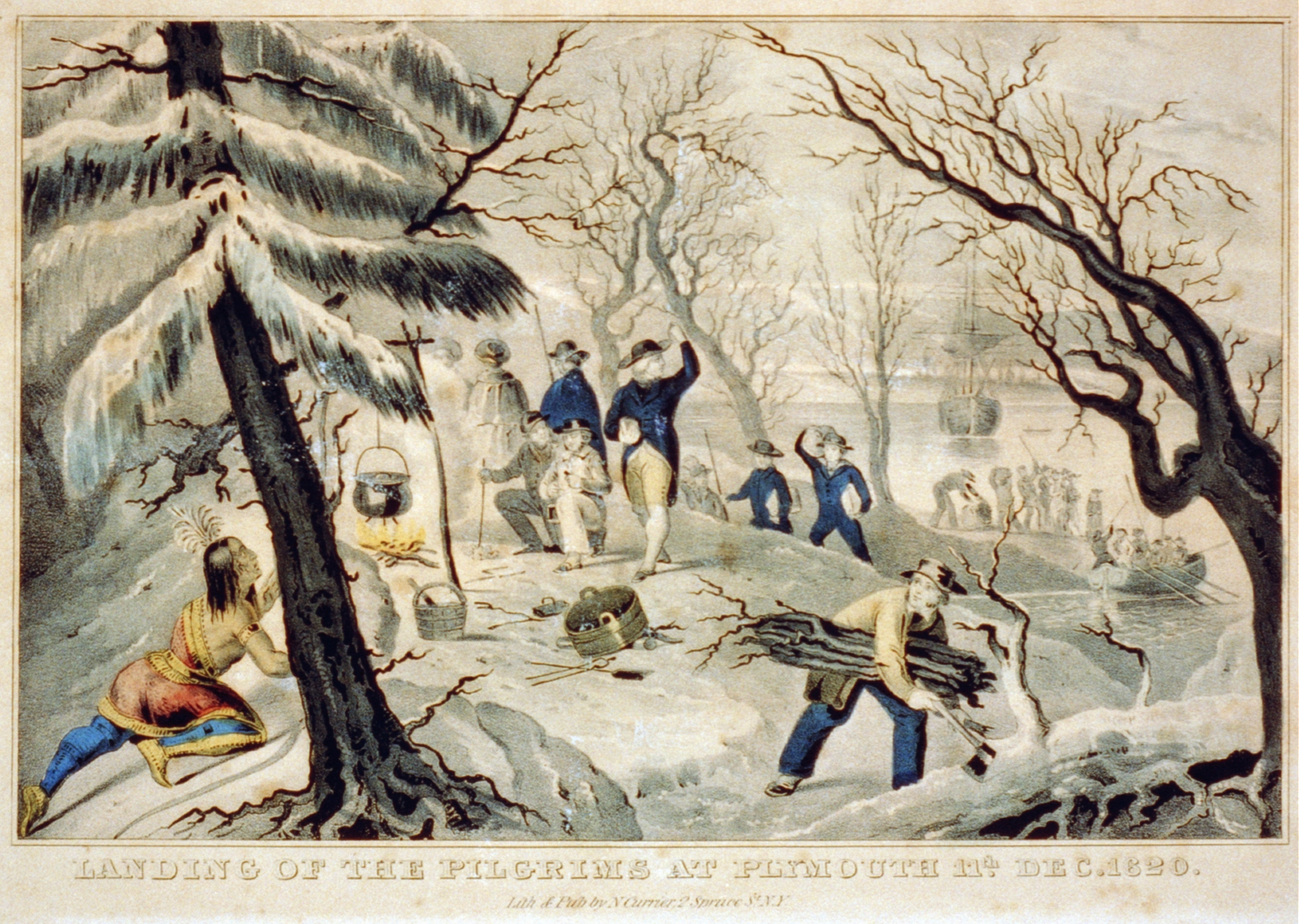

Arguably the most famous group of settlers was the Pilgrims, who founded Plymouth Colony, in present-day Massachusetts, after arriving at Plymouth Rock on the Mayflower in 1620. The Pilgrims were a branch of English Puritans who advocated not just reform of the Church of England, as most Puritans did, but total separation from it. Religious dissent in England was illegal, with fines and imprisonment for those who did not attend Church of England services or who held their own. The Pilgrims fled England both to avoid punishment and to pursue the freedom to worship as they saw fit.

Soon, other religious dissenters in England followed the Pilgrims’ path across the Atlantic. Between 1620 and 1640, approximately 21,000 Puritans made the journey. Puritan settlers in the colonies of New England, particularly in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, lived extremely strict, religious lives. The colonies banned nonreligious entertainment, games, alcohol, and even the celebration of Christmas. They valued education, frugality, family, and hard work—values that would come to typify the American way of life. In this chapter, the poetry of Edward Taylor provides glimpses into the Puritan mind-set and helps us understand colonial life from a religious and spiritual perspective, while Anne Bradstreet’s work explores the struggles of being a woman, and particularly a literary woman, within the confines of the rigid and hierarchical Puritan society.

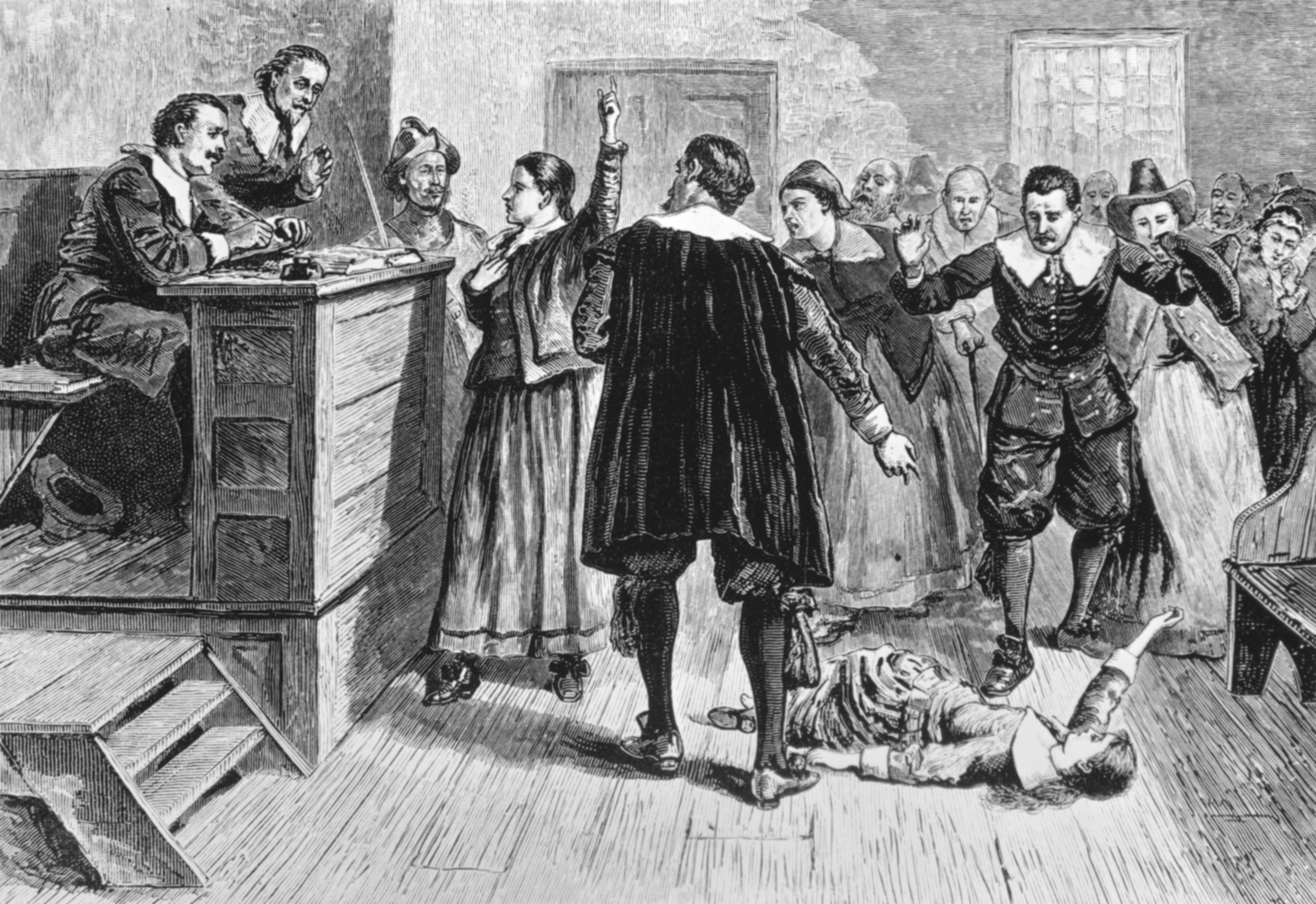

This chapter also explores an ignominious series of events during the Puritan era. The Salem Witch Trials, which occurred in colonial Massachusetts in 1692–1693, are seen through sermons and speeches by Cotton Mather, calling for his fellow Puritans to root out what he and many others believed was the work of the devil, and John Hale, reflecting on the aftermath when the community sought to find a way to heal from the hysteria and injustice.

In the Conversation on the American Jeremiad—a jeremiad being a style of writing and oration that laments a decline while celebrating the possibility of an ideal—you will study more of the sermons of this period. Puritan ministers utilized the rhetorical strategy of the jeremiad to strike fear—and hope—in the hearts and minds of colonists; politicians, religious leaders, and journalists still use it today. When you read the jeremiads, some of which were written centuries apart, you will have an opportunity to think about the ways Puritan literature, culture, and thought remain alive in the contemporary United States.

In this chapter, you will explore the earliest literature of a chaotic new world, formed as two old worlds collided. In this transitional period, a wide assortment of religious refugees, explorers, imperialists, merchants, and indigenous people coexisted—sometimes in harmony, sometimes in conflict—for more than two centuries before anything resembling the United States of America was born. And out of this chaos we begin to see the formation of narratives that define the national character: the Puritan work ethic, a deep spiritual devotion, the pioneering spirit, the self-reliance, and even a nascent feminism, as expressed in the work of Anne Bradstreet. These narratives continue to echo down the corridors of American history.