Gary Edgerton and Kathy Merlock Jackson, from Redesigning Pocahontas: Disney, the “White Man’s Indian,” and the Marketing of Dreams (1996)

Printed Pages 323-329from Redesigning Pocahontas

Disney, the “White Man’s Indian,” and the Marketing of Dreams

Gary Edgerton And Kathy Merlock Jackson

The following selection is from a 1996 critical article on the Disney film Pocahontas. Gary Edgerton is professor and chair of the Communication and Theater Arts Department at Old Dominion University. Kathy Merlock Jackson is professor and coordinator of communications at Virginia Wesleyan College.

It is a story that is fundamentally about racism and intolerance and we hope that people will gain a greater understanding of themselves and of the world around them. It’s also about having respect for each other’s cultures.

— Thomas Schumacher, senior vice president of Disney Feature Animation (Pocahontas 35)

The challenge was how to do a movie with such themes and make it interesting, romantic, fun.

—Peter Schneider, president of Disney Feature Animation (Pocahontas 37)

Don’t Know Much about History

Artists and authors have actually been reshaping Pocahontas and her history for nearly four centuries. In Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend, William M. S. Rasmussen and Robert S. Tilton surveyed literally dozens of depictions, beginning during Pocahontas’s lifetime, when she was “living proof that American natives could be Christianized and civilized” (7). Fact and fiction were blended at the outset into this legendary personality who symbolized friendly and advantageous relations between American Indians and English settlers from a distinctly Anglo-American point of view. Disney’s animators are merely part of that longer tradition, the latest in a series of storytellers, painters, poets, sculptors, and commercial artists who have taken liberties with Pocahontas’s historical record for their own purposes (Rasmussen and Tilton).

Disney’s Pocahontas is, once again, a parable of assimilation, although this time the filmmakers hinted at a change in outlook. Producer James Pentecost for instance reported that

“Colors of the Wind” perhaps best sums up the entire spirit and essence of the film…this song was written before anything else. It set the tone of the movie and defined the character of Pocahontas. Once Alan [Menken] and Stephen [Schwartz] wrote that song, we knew what the film was about. (Pocahontas 51–52)

Schwartz agreed with Pentecost, adding that his lyrics were inspired by Chief Seattle’s famous speech to the United States Congress that challenged white ascendancy in America and the appropriation of American Indian lands (Pocahontas 52).

“Colors of the Wind” functions as a rousing anthem for Pocahontas, extolling the virtues of tolerance, cross-cultural sensitivity, and respect for others and the natural environment:

You think you own whatever land you

land on

The earth is just a dead thing you can

claim

But I know ev’ry rock and tree and

creature

Has a life, has a spirit, has a name

You think the only people who are

people

Are the people who think and look like

you

But if you walk the footsteps of a stranger

You’ll learn things you never knew

You never knew.

5

These lofty sentiments, however, are down-played by the film’s overriding commitment to romantic fantasy. Pocahontas, for example, sings “Colors of the Wind” in response to John Smith’s remark that her people are “savages,” but the rest of the technically stirring sequence plays more like an adolescent seduction than a lesson teaching Smith those “things [he] never knew [he] never knew.”

Pocahontas’s search for her “dream,” a classic Disney plot device, is a case in point. A great deal of dramatic energy is spent on Pocahontas’s finding her “true path.” She is sprightly, though troubled, in her conversations with Grandmother Willow. She is struggling with her own youthful uncertainties as well as her father’s very definite plans for her:

Should I choose the smoothest course

Steady as a beating drum

Should I marry Kocoum

Is all my dreaming at an end?

Or do you still wait for me, dreamgiver

Just around the river bend?

Unsure of Kocoum, but regarding love and marriage as her only options, Pocahontas finally finds her answer in John Smith.

What this development discloses, of course, is the conventional viewpoint of the filmmakers: Pocahontas essentially falls in love with the first white man she sees. The film’s scriptwriters chose certain episodes from her life, invented others, and in the process shaped a narrative that highlights some events, ideas, and values, while suppressing others. The historical Pocahontas and John Smith were never lovers, she was twelve and he was twenty-seven when they met in 1607. In relying so completely on their romantic coupling, however, Disney’s animators minimize the many challenging issues that they raise—racism, colonialism, environmentalism, and spiritual alienation.

The entire plot structure is similarly calculated to support the Disney game plan. The film begins in London in 1607 with John Smith and the Virginia Company crew setting out for the New World, and it concludes with Smith’s return trip to England in 1609, although the duration of the movie seems to span weeks rather than years. The scriptwriters, nevertheless, terminate the narrative at the most expedient juncture, avoiding the more tragic business of Pocahontas’s kidnapping by the English; her isolation from her people for a year; her ensuing conversion to Christianity; her marriage and name change to Lady Rebecca Rolfe; and her untimely death from tuberculosis at age twenty-one in England (Barbour; Fritz; Mossiker; Woodward). Disney’s filmmakers did, in fact, research those details of Pocahontas’s life before starting production, but obviously their aim was to keep audiences as comfortable as possible by providing a predictable product.

10

Co-director Eric Goldberg later claimed that “it’s important for us as filmmakers to be able to say not everything was entirely hunky-dory by the end…which it usually is in a traditionally Disneyesque movie” (Mallory 24). Given the eventual fate of Pocahontas and the Algonquins, though, Disney’s animators could hardly have opted for the usual “happily ever after” finale. The filmmakers, after all, were genuinely trying to offend no one, including the Native American community and their consultants.

Pocahontas’s climactic sequence further establishes the film’s dominant, love-story narrative, albeit with some variations of the classic Disney formula. After English settler Thomas shoots and kills Kocoum, tensions between the American Indians and the British mount. John Smith is captured by Kocoum’s companions, blamed for his death, and immediately slated for execution. In a replay of the legendary rescue scene, Pocahontas risks her life to save John Smith, catalyzing peace between the English and the American Indians. In the process, the film’s animators and scriptwriters complete their upgrade of the Indian princess characterization by making Pocahontas more assertive, determined to realize her “dream,” and according to her father, “wis[e] beyond her years.”

The film, moreover, concludes with Pocahontas standing alone on a rocky summit, watching the ship carrying a wounded John Smith sail for England. She has presumably resolved to stay behind in Virginia and take her rightful place alongside her father as a peacemaker, even though her actions in the previous eighty minutes of the film suggest that her “path” lies elsewhere. Pocahontas thus reinforces another resilient stereotype that the main purpose of a Disney heroine is to further the interests of love, notwithstanding the bittersweet coda. Pocahontas’s newfound ambition to become a mediator, then, is a workable if somewhat disingenuous solution, especially considering the latent historical realities percolating beneath this romantic plotline.

The questions then arise: Can a Disney animated feature be substantive as well as entertaining? Can race, gender, and the rest of [the] Pocahontas postmodernist agenda be presented in a thought-provoking way that still works for the animation audience, especially children? We believe the answer is yes, but we also believe the studio has an obligation to create a more forward-looking alternative to existing stereotypes and to deal more fully and maturely with the serious issues and charged imagery that it addresses.

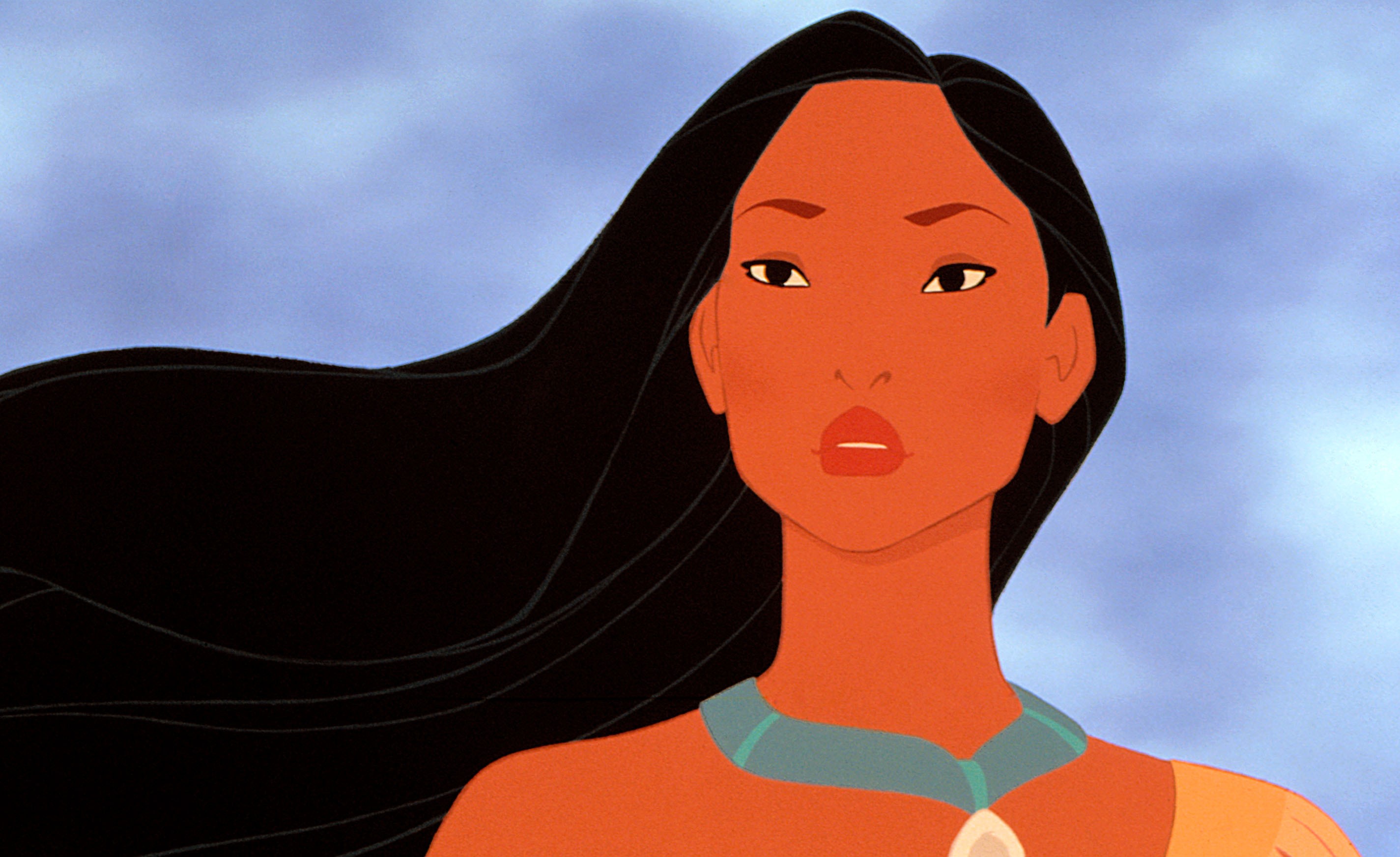

Consider the redesigning of the character of Pocahontas. Supervising animator Glen Keane remembered how former studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg charged him with reshaping Pocahontas as “the finest creature the human race has to offer” (Kim 24). He also admitted, “I don’t want to say a rut, but we’ve been doing mainly Caucasian faces” (Cochran 42). Keane, in turn, drew on four successive women for inspiration, beginning with paintings of Pocahontas herself; then Native American consultant Shirley “Little Dove” Custalow McGowan; then twenty-one-year-old Filipino model Dyna Taylor; and finally white supermodel Christy Turlington (Cochran 42). After studio animators spent months sketching her, their Pocahontas emerged as a multicultural pastiche. They started with Native American faces but eventually gravitated to the more familiar and Anglicized looks of the statuesque Turlington. Not surprisingly, all the key decision makers and supervising artists on Pocahontas were white males. Disney and Keane’s “finest creature” clearly is the result of a very conventional viewpoint.

15

Accordingly, what of avoiding old stereotypes? Native American actors were cast in all the native roles in the film; still, Pocahontas’s screen image is less American Indian than fashionably exotic. Many critics, for example Newsweek’s Laura Shapiro, refer to the makeover as “Native American Barbie” (Shapiro and Chang 57)—in other words, Indian features, such as Pocahontas’s eyes, skin color, and wardrobe, only provide a kind of Native American styling to an old stereotype.

The British colonists also replace the Indians as stock villains in Pocahontas, with Governor Ratcliffe, in particular, singing about gold, riches, and power in the appropriately titled song “Mine, Mine, Mine.” The film’s final impression, therefore, is that, with Ratcliffe bound, gagged, and headed back to England, American Indians and Europeans are now free to coexist peacefully. Race is a dramatic or stylistic device, but the more profound consequences of institutional racism are never allowed even momentarily to invade the audience’s comfort zone.

Perhaps the Disney studio should trust its patrons more. Fairy tales and fantasies have traditionally challenged children (and adults) with the unpleasant realities lurking just beneath their placid exteriors. Audiences are likely to enjoy added depth and suggestiveness enough to buy plenty of tickets and merchandise. Disney’s Pocahontas raises important issues but does not fully address them; it succeeds as a king-sized commercial vehicle, but fails as a half-hearted revision.

Contested Meanings

The meaning of a text is always the site of a struggle.

—Lawrence Grossberg (86)

History is always interpreted. I’m not saying this film is accurate, but it is a start. I grew up being called Pocahontas as a derogatory term. They hissed that name at me, as if it was something dirty. Now, with this film, Pocahontas can reach a larger culture as a heroine. No, it doesn’t make up for five hundred years of genocide, but it is a reminder that we will have to start telling our own stories.

—Irene Bedard (qtd. in Vincent e5)

The comments of Irene Bedard, the Native American actress who plays the voice of Pocahontas, augment many of the critical responses that surfaced after the release of Pocahontas in the summer of 1995. She offers audiences some valuable insights into the Native American perspective, especially with her painful recollection of being ridiculed with the surprising taunt, “Pocahontas.” As she says, this film signals a welcomed counterbalance to such insults; most significantly, she calls for the emergence and development of a truly American Indian cinema that is the next needed step for fundamentally improving depictions of Native Americans on film.

Until that time, however, we can extend our understanding of Pocahontas, in particular, and established and alternative views toward Indian people in general, by examining the spectrum of critical reactions that the animated film engendered. The most striking aspect of Pocahontas’s critical reception is the contradictory nature of the responses: the film is alternately described as progressive or escapist, enlightened or racist, feminist or retrograde—depending on the critic. Inherently fraught with contradictions, Disney’s Pocahontas sends an abundance of mixed messages, which probably underscores the limits of reconstructing the Native American image at Disney or, perhaps, any other major Hollywood studio that operates first and foremost as a marketer of conventional dreams and a seller of related consumer products.

Works Cited

Barbour, Philip L. Pocahontas and Her World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970. Print.

Cochran, Jason. “What Becomes a Legend Most?” Entertainment Weekly 16 June 1995: 42. Print.

Fritz, Jean. The Double Life of Pocahontas. New York: Puffin, 1983. Print.

Grossberg, Lawrence. “Reply to the Critics.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 3 (1983): 86–95. Print.

Kim, Albert. “Whole New World?” Entertainment Weekly 23 June 1995: 22–25. Print.

Mallory, Michael. “American History Makes Animation History.” The Disney Magazine Spring 1995: 22–24. Print.

Mossiker, Frances. Pocahontas. New York: Knopf, 1976. Print.

“Pocahontas: Press Kit.” Burbank: Walt Disney Pictures, 1995. Print.

Rasmussen, William M. S., and Robert S. Tilton. Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend. Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1994. Print.

Shapiro, Laura, and Yahlin Chang. “The Girls of Summer.” Newsweek 22 May 1995: 56–57. Print.

Vincent, Mall. “Disney vs. History…Again.” Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star 20 June 1995: E1, E5. Print.

———. “‘Pocahontas’: Discarding the History, It’s still a Terrific Show.” Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star 24 June 1995: E1–E2. Print.

Woodward, Grace Steele. Pocahontas. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1969. Print.

(1996)