Chapter 7 America in Conflict: 1830-1865

Printed Pages 547-5511830–1865

As America entered the mid-nineteenth century, the nation was experiencing widespread expansion in almost every conceivable way. In 1830, nearly all land west of the Missouri border was either unorganized territory or controlled by Mexico, but by 1865, the United States would control the continent from shore to shore. America’s population grew at unprecedented rates during this period, from 13 million people to more than 30 million. Expansion in territory and population went hand in hand with technological innovations and massive infrastructure improvements. The Erie Canal, finished in 1825, enabled shipping from New York Harbor into the middle of the country via the Great Lakes, turning New York City into the nation’s most important port. Steamboats and steam locomotives became viable forms of transportation, and thirty-five thousand miles of railroad track were laid down across the country. Steam-powered manufacturing equipment was invented, including printing presses for books and newspapers. And yet, this industrialization and urbanization was not uniform across the nation: while cities and manufacturing boomed in Northern states, the Southern economy remained largely agrarian, slave based, and highly lucrative for landowners thanks to cotton, a cash crop that would account for roughly 60 percent of America’s exports.

The promise of economic opportunity and cheap farmland lured millions of emigrants from Europe, particularly from Ireland, Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe. America’s westward expansion drew settlers into uncharted territory as wagon trains braved the Oregon Trail. The discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s initiated a gold rush, drawing even more people west. One group of people, however, did not go by choice. As the American population continued to grow, the Native American populations in the East were driven onto reservations and Indian Territories in the West. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson, relocated the Cherokee, Seminole, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, and Choctaw tribes from their homelands in the American Southeast to what would become Oklahoma. The thousand-mile journey was long and arduous, and each tribe would suffer heavy losses from disease, exposure to the elements, and insufficient rations, though perhaps none suffered as much as the Cherokee, who lost nearly half of their population. The route of the forced relocation would come to be called the “Trail of Tears.” One important voice regarding the treatment of Native Americans during this period was that of Chief Seattle, whose defiant message to President Franklin Pierce in 1854 is included in this chapter.

Increasing industrialization, along with an expanding frontier, created a shifting natural landscape as wilderness became increasingly settled and developed. A new adventurous and romantic spirit began to express itself in American arts, especially in the poetry of William Cullen Bryant and in the paintings of Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. An “American Renaissance,” in the words of literary critic F. O. Matthiessen, began in Concord, Massachusetts, and its hopeful optimism flourished in the writings of transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson and in the poetry of Walt Whitman. Emerson, the “sage of Concord,” would become the most influential writer of the century, and his essay “Self-Reliance” is regarded as the quintessential expression of the American spirit. The darker, more skeptical side of romanticism could be seen in the brooding fiction of such writers as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne (who called his fictional works not stories and novels but “tales” and “romances”), and Herman Melville, the author of Moby-Dick, a book considered by many modern critics to be the greatest American novel, the only other contender from the nineteenth century being The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. In this chapter, you will encounter readings by these writers and enter a Conversation about Henry David Thoreau, the transcendentalist writer who temporarily rejected urban society in Massachusetts for a solitary life in the woods near Walden Pond. Readings by and about Thoreau will ask you to investigate how and why he still matters and why his ideas resonate today.

While romanticism ran through much of early American literature, its hopeful optimism could hardly be said to express the feelings or conditions of three groups of Americans: slaves, Native Americans, and women. They were simply excluded from the American promise. At the same time, this period also became one of immense social reform. Public schools were instituted, prisons were reenvisioned as institutions of reform rather than punishment, debtors’ prisons were abolished, and women’s rights became a serious issue, which you will find expressed in the writings of Sojourner Truth and Margaret Fuller included in this chapter.

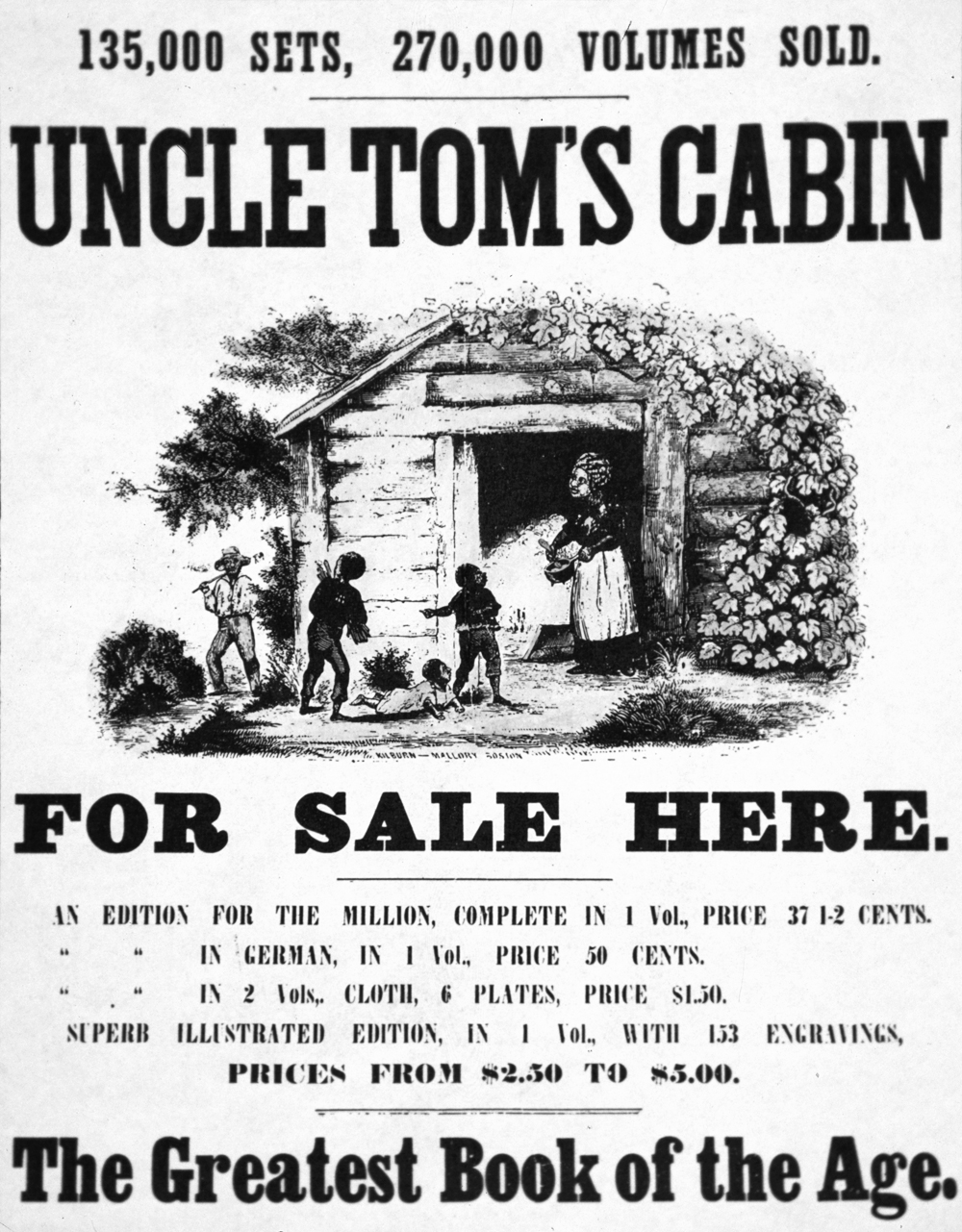

Doubtless the most active reformers were the abolitionists. Abolitionist groups and newspapers such as the Liberator flourished in the Northeast. Slave narratives by Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), revealed the horrors of slavery to a wide reading public and helped make the moral case for abolition. In 1850, the brutal Fugitive Slave Act established that escaped slaves must be returned to their masters, and in 1857 the Dred Scott decision in the Supreme Court declared that Africans in America held no constitutional rights. A Conversation in this chapter explores one controversial abolitionist whose dramatic actions arguably lit the fuse that started the American Civil War and ended slavery in the United States. In 1859, John Brown raided the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an effort to arm a slave rebellion in the South. His small band was overwhelmed by troops, and Brown was captured, convicted, and hanged. In “The Last Days of John Brown” (1860), Thoreau writes, “They all called him crazy then; who calls him crazy now?” Was John Brown a hero fighting to abolish an inhumane practice and free an enslaved people, or a madman and terrorist who attacked his own nation? These are questions you will consider as you read the sources in the Conversation on this controversial figure from the nineteenth century.

Having campaigned on a platform against the expansion of slavery beyond states in which it already existed, Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860. The next year, representatives of the Southern slave states formed the Confederate States of America. Prior to Lincoln’s inauguration as president, the first seven Confederate states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—declared their secession from the Union in the early months of 1861. Then Confederate forces fired on the United States military base at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, and Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina seceded quickly thereafter.

Barely a century after the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the completion of the American Revolution, the American republic was torn asunder by a deadly civil war. The United States of America—its mission, its principles, and its future—was in jeopardy. In 1863, at the height of the national crisis, President Abraham Lincoln commemorated a cemetery on the site of the battlefield at Gettysburg with these famous words: “We here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people by the people for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Lincoln’s speech, a mere ten sentences long, expressed the president’s determination to preserve the Republic and gave hope to the young and fragile nation. In this chapter, you will read more of Lincoln’s works and reflections from thinkers both then and now in a Conversation on the president whom many have come to call the Great Emancipator.

Over the course of four years, the American Civil War took the lives of over 1 million people, approximately 700,000 of them soldiers. But perhaps, as Lincoln had hoped, those million did not die in vain—the Emancipation Proclamation freed approximately 3.5 million slaves in the Southern states, and the Thirteenth Amendment, adopted several months after the war’s conclusion, outlawed slavery in the United States. On April 9, 1865, at Appomattox, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant, and as the news spread, Confederate forces throughout the South surrendered over the following days. Then, five days after Lee’s submission, in one of the greatest tragedies in American history, President Lincoln was shot and killed by John Wilkes Booth, a Southern sympathizer.

The America of this chapter is one that is emerging from great promise and great conflict into a multifaceted and complex nation, and through its literature, we can examine its triumphs, its tragedies, its growing pains, and its rebirth.