Chapter 8 Reconstructing America: 1865—1913

Printed Pages 823-8281865–1913

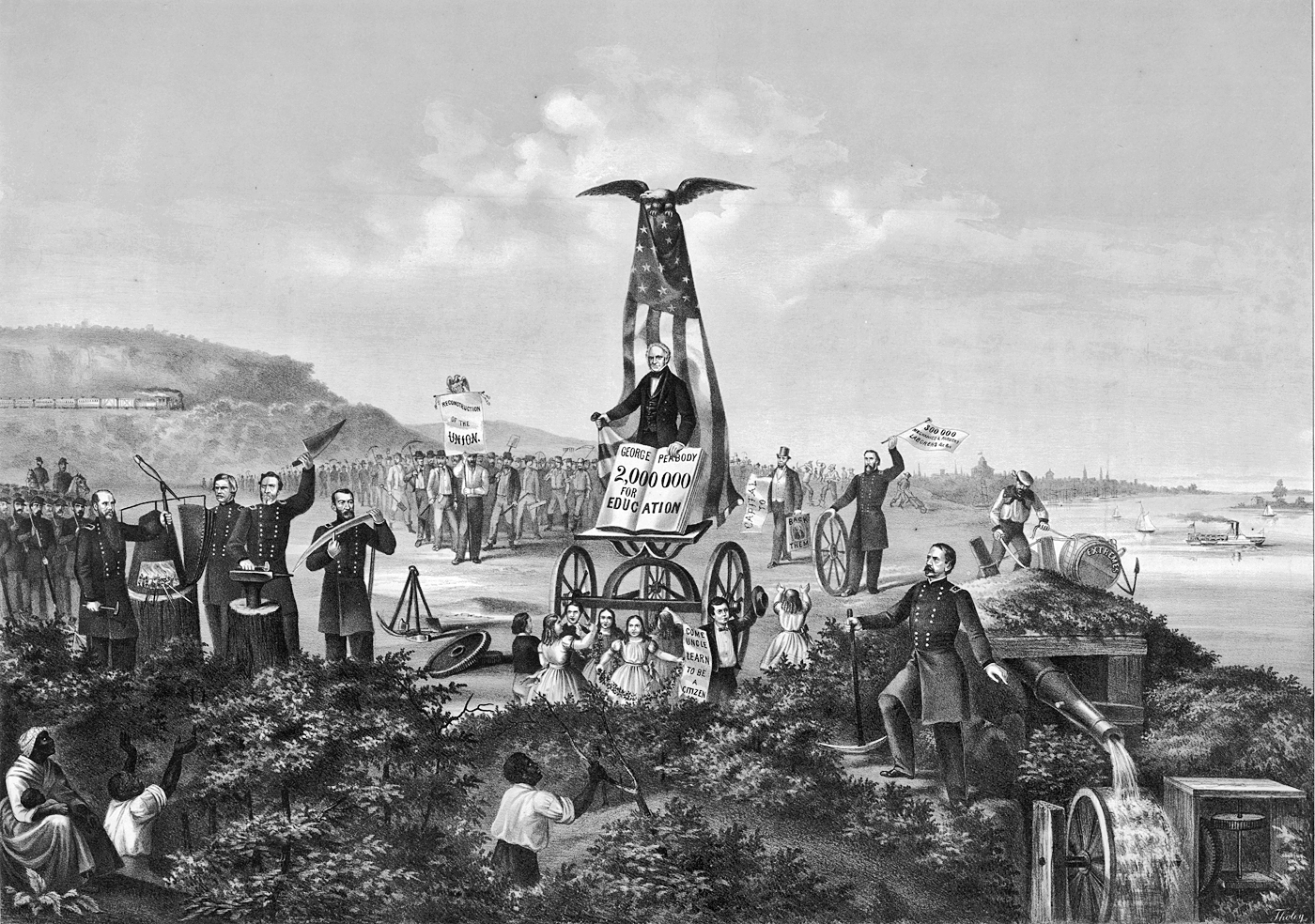

After the Civil War, the United States grappled with its aftermath, both joyous and mournful. How should the newly unified nation ensure the rights of millions of newly freed slaves? How should it rebuild the South and its political systems while reuniting the nation? What should be done with the leaders of the Confederacy? Presidents Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, and Ulysses S. Grant implemented policies to tackle these questions, policies that collectively came to be called Reconstruction. The issue of ensuring the rights of newly freed slaves was addressed by the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which outlawed slavery and granted African Americans citizenship, the right to vote, the rights of due process, and equal protection under the law. After the war, the Southern states came under the authority of the Union army, and with Reconstruction, they began again to self-govern and to have representation in the U.S. Congress. These new governments, often biracial, established public schools and charitable institutions, and raised taxes to support public works such as construction projects and transportation networks.

Despite what most believe were the good intentions of Reconstruction, the decade following the Civil War remained a period of violence and division. Racial tensions and discrimination flourished, as groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and the Red Shirts terrorized African Americans, while regressive white politicians regained enough power to institute the discriminatory Jim Crow laws. In this chapter, readings by Paul Laurence Dunbar and Ida B. Wells-Barnett explore the pain and suffering of the African American population during this time, and correspondence between the newly freed Jourdon Anderson and his former master reveals a new American power structure. Writings by Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois highlight contrasting approaches to the education and leadership of African Americans as they assumed their full rights and responsibilities as citizens.

America experienced its most rapid westward expansion in this post–Civil War period. The Homestead Act of 1862 provided opportunities for Americans to own undeveloped federal land west of the Mississippi at no cost. This, along with mining, ranching, and the spirit of exploration and adventure, drew Americans westward. Between 1862 and 1934, 1.6 million homesteads were granted, privatizing 420,000 square miles of American land—about 10 percent of the land in the United States. Applicants for homesteads were required to be the heads of their households or at least twenty-one years old; they had to live on the land for at least five years, build a home, and start a farm or ranch. Conditions in the American “Wild West” were notoriously difficult, and only about 40 percent of homestead applicants completed their five-year commitment and received the title to their land.

Much of this westward expansion was facilitated by the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, which made travel to the West much faster and safer than it had been by wagon train. While seen as a reflection of technological innovation and inevitable “progress,” the transcontinental railroad relied on cheap labor primarily provided by Chinese immigrants. At one point, 8,000 of the 10,000 men toiling for the Central Pacific Railroad were Chinese. Public concern about the impact of these workers on the labor force led to passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which prohibited immigration from China for the next ten years.

Westward expansion occurred at the expense of Native American populations, who were dislocated and relocated to make room for settlers. Both the settlers and the U.S. Army sent to protect them frequently met with resistance from displaced tribes, leading to skirmishes and outright battles. These conflicts have since been elevated by Hollywood and storytellers to the level of American mythology, particularly the figure of the American cowboy. Romanticized as a brave loner who embodied the “rugged individualist” of the dime novels that popularized this image, the cowboy became a powerful part of the national narrative. A Conversation in this chapter explores the evolution of this mythic figure and considers his impact on the national character, as well as his more contemporary incarnations.

In his groundbreaking speech in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition, a celebration of the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World, Frederick Jackson Turner lamented the “closing” of the frontier and what that loss of a sense of infinite boundaries would mean for the national identity. His “Frontier Thesis” provided a foundation for manifest destiny, an ideology that justified territorial expansion to the Pacific Ocean and annexation of Pacific territories.

As the nation expanded, so too did its population. From the 1850s to the 1860s, immigration nearly doubled, and it continued to increase steadily until the 1930s. In this period, immigrants were primarily Europeans lured to America by the promise of freedom and prosperity. A Conversation about immigration in this chapter will ask you to consider “the lure of America” and reflect on attitudes toward immigrants both then and now.

Much of the immigrant population clustered in American urban metropolises, driven there in large part by jobs created by rapid industrial growth. In the years approaching the turn of the twentieth century, America was leading the world in the production of iron and steel, producing half of the world’s cotton, corn, and oil, and mining a third of its gold and coal. As industrialization flourished, products became cheaper, giving Americans unprecedented buying power. For some, rapid industrialization meant economic prosperity and cheaper consumer goods. This resulted in the growth of a new middle class, a group who worked to live but also enjoyed leisure time, vacations, and entertainment ranging from sporting events to vaudeville shows to carnival amusements. Department stores and mail-order catalogs became prevalent. Advances in electricity revolutionized America’s living and working spaces. The trolley car and the train transported Americans with extraordinary speed and convenience.

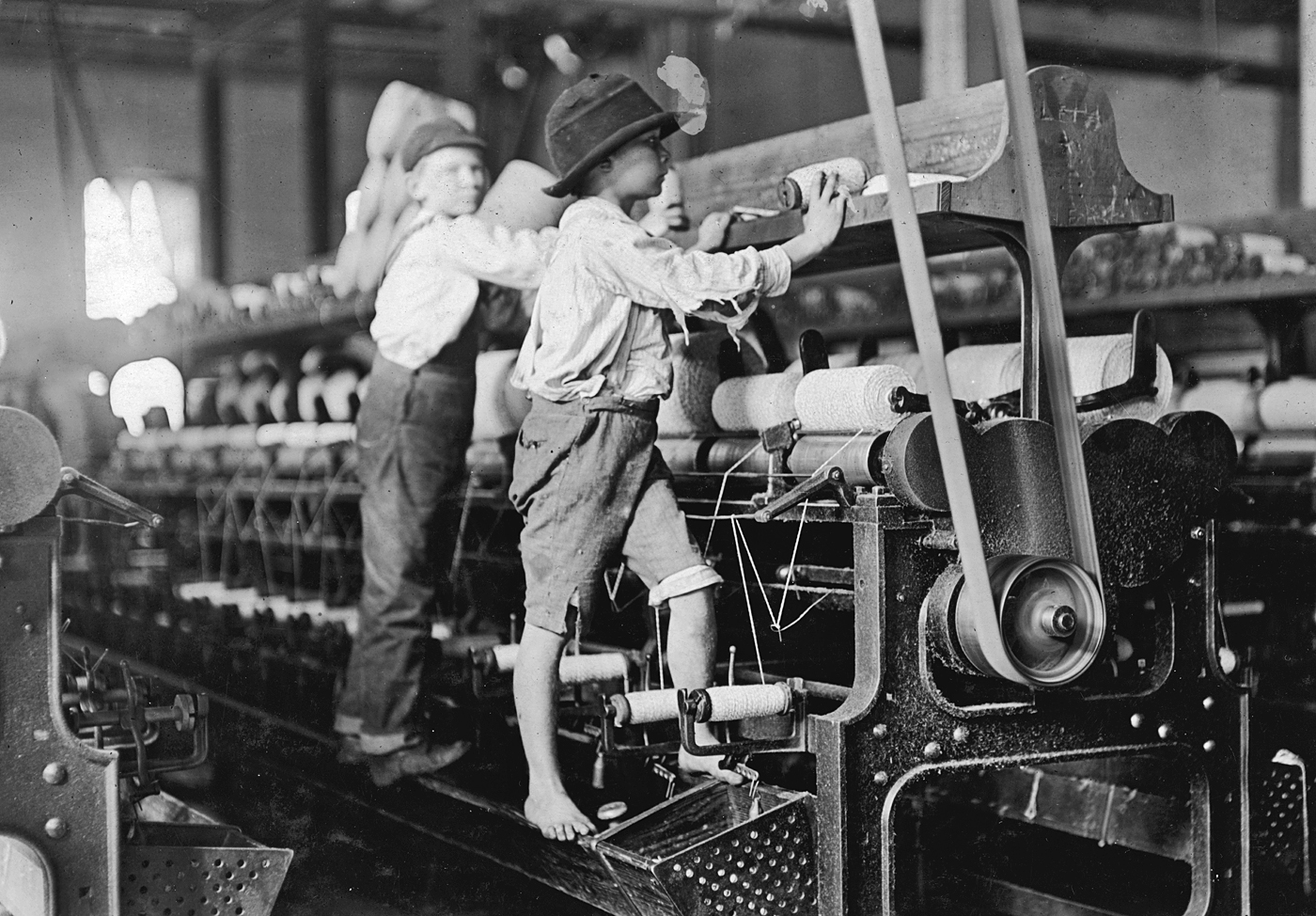

But despite these advances, most Americans were not wealthy, and urban life was particularly harsh in this period. Inhabitants of the cities experienced extreme overcrowding, crushing poverty, and disease. Children and adults toiled in factories. Schooling was still a luxury. Governments provided no social safety nets for their constituents. The gap between the rich and the poor became so vast that, as the saying goes, “one half of the world does not know how the other half lives.” Jacob Riis took that old saying as the inspiration for his groundbreaking work of photojournalism, How the Other Half Lives, which illustrated the squalid conditions of New York’s slums and tenement houses and exposed the country’s middle and upper classes to these images for the first time. A selection of his writing, along with some of his stunning photographs, can be found in this chapter. Also included in this chapter are excerpts from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, a fictional—though appallingly realistic—depiction of the treatment of workers in a Chicago meatpacking plant, and Twenty Years at Hull House, the memoir of Jane Addams, a social reformer and founder of one of America’s first settlement houses. She writes of the poverty and abuse that pervaded Chicago and her hope to uplift her city and community through progressive reform, democratic and egalitarian social and political institutions, and suffrage and economic opportunity for all.

During this period, workers facing low wages, long hours, and dreadful living conditions collided with growing corporations that amassed enormous wealth for a few individuals. Movements emerged to improve working conditions and address growing economic inequality. Laborers organized to fight for wages, benefits, and rights. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (later to become the American Federation of Labor) was founded in 1881. Though child labor did not formally come to an end until the 1930s, the National Child Labor Committee formed in 1904 and dedicated itself to eradicating the practice. Women began calling for full voting rights that would, for one thing, ensure they had a stronger influence over working conditions for children and for themselves. While the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the right to vote was not ratified until 1920, political and social activism during the late 1800s and early 1900s laid the foundation for passage of that legislation.

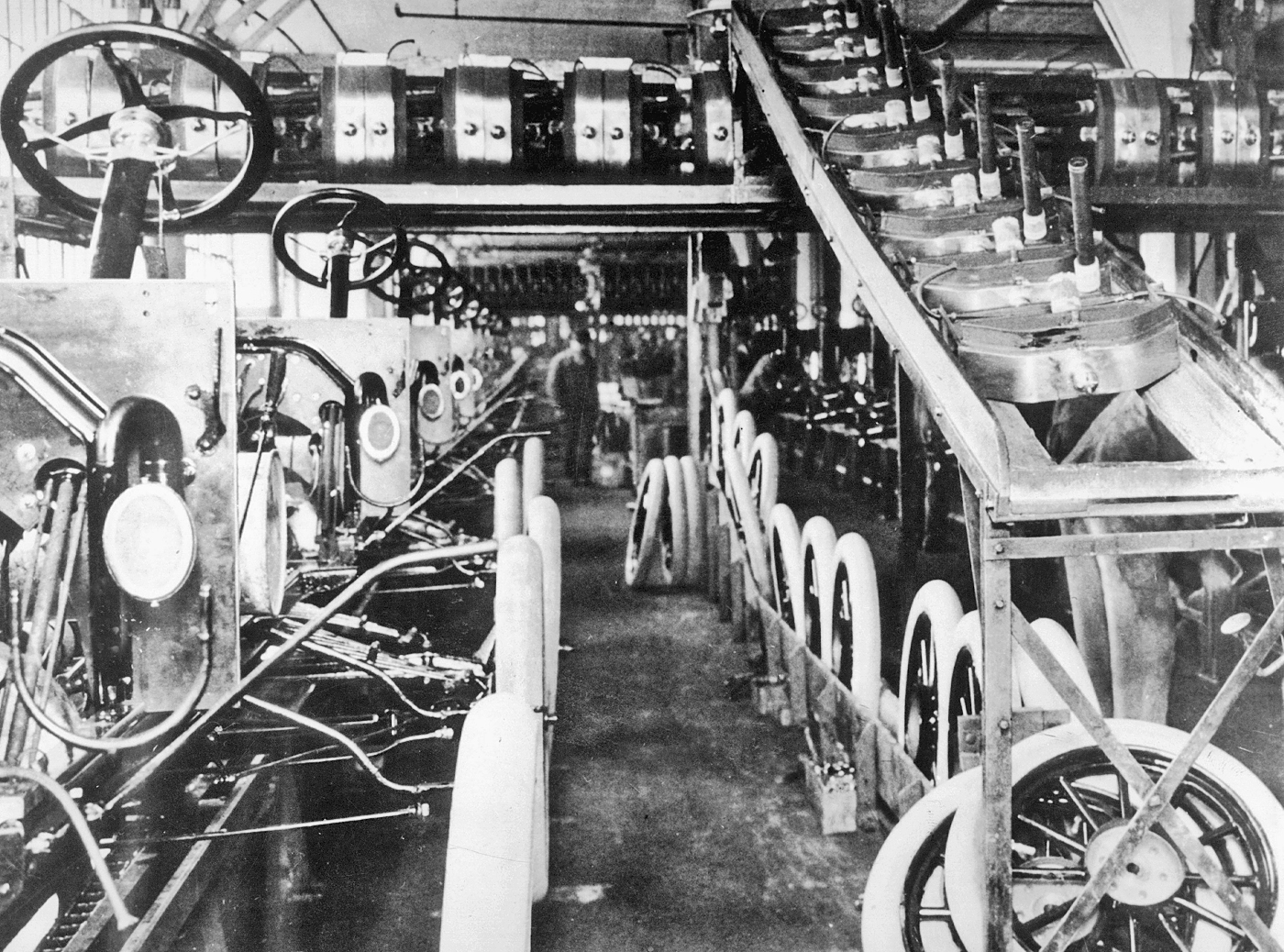

Despite the hardships endured during this period, it was also an exciting time of technological progress that would forever change Americans’ way of life. The automobile began to be mass manufactured in 1901 by the Ransom E. Olds company, which would later become Oldsmobile. The Wright Brothers completed the first powered flight at Kitty Hawk. Kodak began manufacturing the first portable camera. Guglielmo Marconi sent the first successful radio communication. Thomas Edison invented the alkaline battery, the lightbulb, the phonograph, and the kinetophone—or talking motion picture. Einstein published his theory of special relativity in 1905, which, among other things, explained gravity as a curvature in space-time and laid the groundwork for the field of nuclear physics by revealing the relationship between mass and energy: E = mc2.

Our national literature flourished in this era. Technologies such as the use of automated presses and the invention of the linotype machine resulted in wide dissemination of printed materials. These advances along with the rapid growth of public libraries and increased literacy rates made reading a national pastime—and a big business. By the end of the century, the term “best seller” had entered the American vernacular.

Though some of the wounds of the Civil War had been healed, westward expansion was giving way to imperialistic calls for a global presence, and changing demographics brought demands for more equitable political and social conditions. On July 4, 1913, the nation symbolically looked both backward and forward when more than fifty thousand veterans came together to commemorate the Battle of Gettysburg. In his Independence Day speech, President Woodrow Wilson struck a conciliatory note, saying:

Do not put uniforms by. Put the harness of the present on. Lift your eyes to the great tracts of life yet to be conquered in the interest of righteous peace, of that prosperity which lies in a people’s hearts and outlasts all wars and errors of men.

Yet the harmonious respite was brief; one year later, on August 14, 1914, the United States entered World War I.