Chapter 10 Redefining America: 1945 to the Present

Printed Pages 1279-12851945 to the Present

On August 6 and August 9, 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, simultaneously marking the end of World War II and the beginning of a new era in which America would become the world’s foremost economic, military, and cultural power.

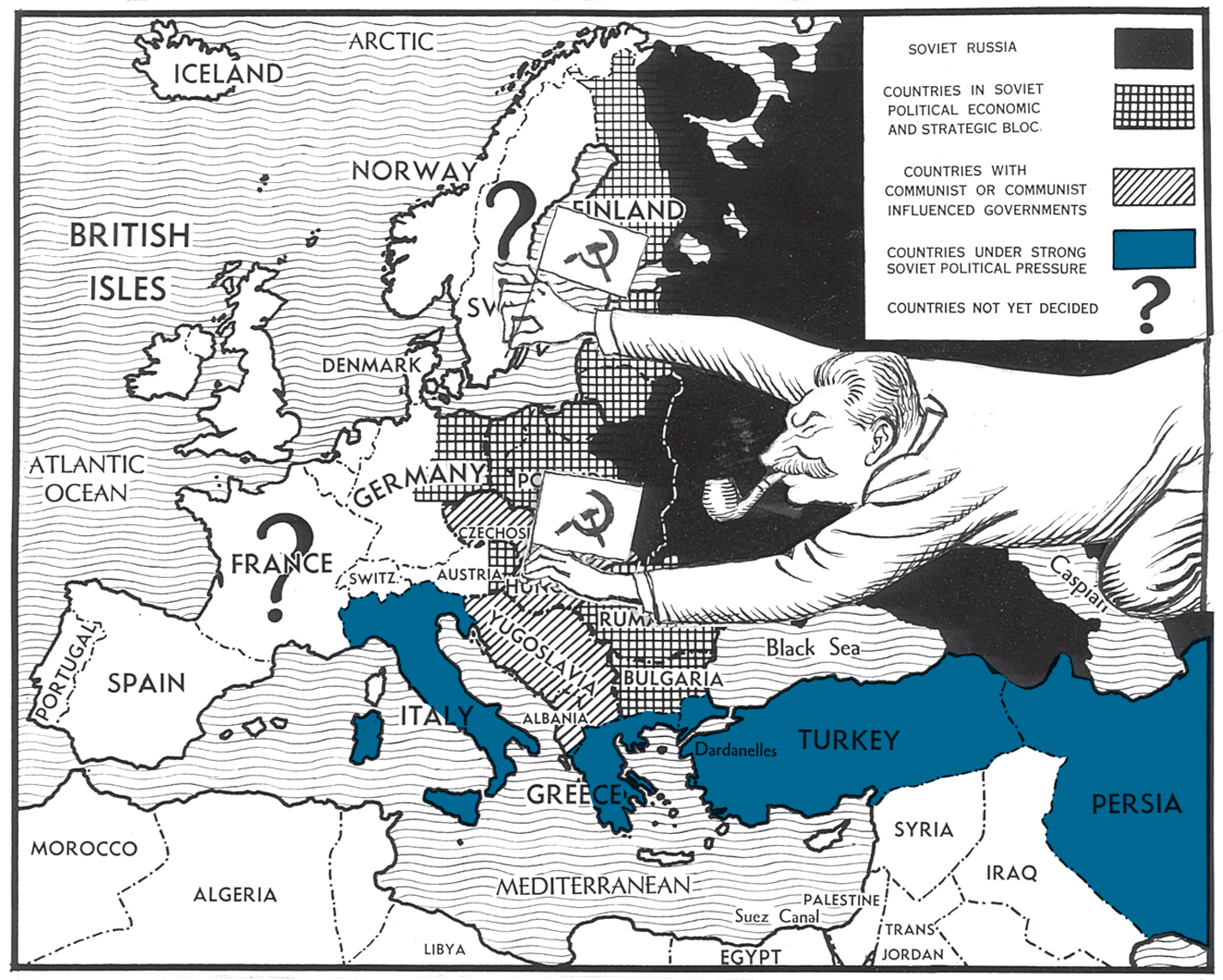

Reluctant allies during the war, America and the Soviet Union emerged from World War II as the sole remaining superpowers, separated by a profound ideological divide between capitalism and Communism, democracy and totalitarianism. As Europe recovered physically and politically, the two superpowers vied for influence over its fate. Western Europe was rebuilt with U.S. help via the Marshall Plan, while the Soviet Union quickly stepped in to seize control of Eastern Europe, setting up satellite states in Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Albania, and Hungary. Caught between the two superpowers, Germany and its capital, Berlin, were divided into East and West, Communist and democratic. Alarmed by the Soviet Union’s expansionist policies in Eastern Europe and beyond, the United States and its allies adopted a policy of containment to stop the spread of Communism. The Cold War had begun, and it would affect American life until the Soviet Union fell in 1991.

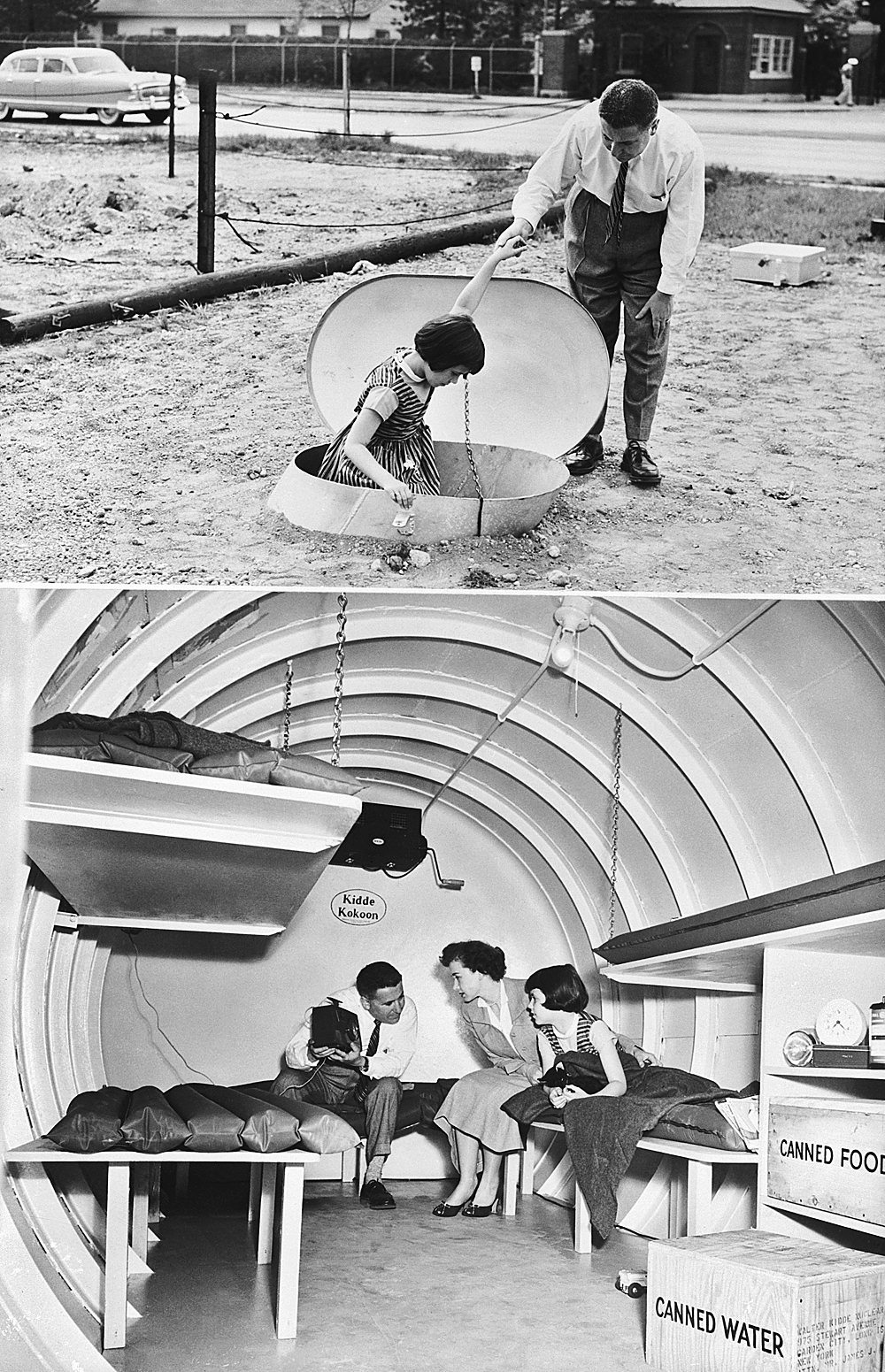

The Soviet Union raised the stakes of the Cold War in 1949, when they shocked the world by successfully testing a nuclear weapon. The Cold War became an arms race, with the threat of nuclear war hanging over American life like a dark cloud. Children learned to duck and cover under school desks in case of a nuclear attack. Families built fallout shelters in their backyards. As William Faulkner said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up?” Adding further paranoia to this Cold War anxiety, a spy ring was uncovered within the Los Alamos nuclear facility. The ring had been relaying top-secret nuclear weapons plans to the Soviets. The threat of Communist infiltration, global Communism, and nuclear war set off a panic, often called the Red Scare, that had Congress searching for Communists within the government, in unions, in education, and in Hollywood. In this chapter, you will read a series of texts about the anxieties of the atomic age and their impact on the present day, including a piece by playwright Arthur Miller in which he explains how commonalities between the hunt for Communists and the Salem Witch Trials inspired him to write The Crucible.

Despite the anxiety, the United States emerged from World War II into a period of previously unimaginable prosperity. Wartime spending and production had pulled the nation out of the economic depression of the 1930s and transformed it into a manufacturing juggernaut that produced newly developed consumer goods, including plastics, passenger jets, dishwashers, refrigerators, washing machines, air conditioners, and televisions. Employment in both white- and blue-collar sectors skyrocketed, as did the American standard of living. The economy grew by a startling 37 percent during the 1950s, and the gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 250 percent between 1940 and 1960. The 1950s saw a corresponding swell in income levels across the board, but particularly in the middle class. In this chapter, you will read a Conversation on the American middle class that asks you to consider the factors that led to its rise during the postwar boom and to reflect on the impact that growing income inequality might have on its future.

Perhaps no product symbolizes the prosperity of the postwar era more than the automobile. Cars and trucks were no longer luxuries or tools but a part of the American way of life, a tangible expression of freedom. By the mid-1950s, there were more than 60 million automobiles on American roads. With the rise of the automobile came an increase in single-family homes (as opposed to apartment buildings or homes intended for extended families), which were often grouped together on the outskirts of a city in suburbs. And as suburbs grew, urban populations declined for the first time in America’s history. In this chapter, you will enter a Conversation about America’s love affair with the automobile. Is it over? Has the impact of suburban sprawl begun to outweigh the call of the open road? Has the automobile’s place in our hearts been replaced by other technologies, or will the open road always be a part of our national identity?

Despite the exuberance of the postwar boom, not everyone shared in the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s. Jim Crow laws made discrimination the law of the land throughout the American South, though de facto segregation existed all over America. In this chapter, you will read James Baldwin’s “Notes of a Native Son” which gives a glimpse of the emotional toll racial discrimination takes on its victims. Things began to change in 1954, with the heroic efforts of the civil rights movement. The Selma-to-Montgomery marches, the Montgomery Bus Boycott begun by Rosa Parks, the simple ordering of a cup of coffee at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina—these are iconic events in our nation’s history. In this chapter, poet Rita Dove brings Rosa Parks’s actions to life in her poem “Rosa.” In the spring of 1963, during a protest to desegregate the shops in downtown Birmingham, Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr. and thousands of others were arrested. In jail, on smuggled scraps of paper, King wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” which you will read in this chapter. It is paired with a TalkBack essay by Malcolm Gladwell, who contends that Twitter and other social networks are not capable of generating the dramatic campaigns and lasting change that the civil rights movement achieved.

Throughout the 1960s, the Cold War continued to smolder. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world as close as it has ever come to all-out nuclear war. And in Asia, the United States sent troops into Vietnam ostensibly to prevent a Communist takeover of South Vietnam by the Soviet-backed North Vietnamese. Despite protests at home—especially on college campuses—the United States supported its actions based on a belief in the domino theory, which held that if one country in a region fell to Communism, others would follow. The Vietnam War lasted for more than a decade and a half, ending in 1975 and costing the lives of 58,000 U.S. soldiers and as many as 2 million Vietnamese. Tim O’Brien’s “On the Rainy River” tells the tale of a young man who gets drafted and has to deal with the competing ethical demands of serving his country and serving his own conscience. Veteran Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Facing It” describes the emotional experience of a soldier viewing the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, patterns of immigration to the United States shifted. The number of immigrants from Europe declined, while the number from Mexico, Central and South America, and South and East Asia increased. And whereas assimilation had been the mantra for European immigrants, multiculturalism became the byword for the new immigrants, who were reluctant to give up their traditions and identities. Multiculturalism challenged and redefined what it means to be an American. In this chapter, you will read pieces by Naomi Shihab Nye, Judith Ortiz Cofer, Li-Young Lee, and others who give voice to this new, more inclusive, America.

The women’s rights movement of the late 1960s changed the American workplace, economy, and family structure. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1950 about 34 percent of women held jobs; by 1980, that number grew to 51 percent, and by 1990, that number grew to 60 percent. Dual-income families have largely replaced single-income families. In this chapter, you will read pieces by Adrienne Rich and Stephen Jay Gould that explore the literary and scientific thinking that resulted in greater equality for women in American culture.

As America entered the twenty-first century, it experienced perhaps its greatest tragedy and challenge: 9/11 was the defining event of that decade. The wars it spawned and the impact it had on American culture continue to be felt more than a decade later. In this chapter, you will consider Art Spiegelman’s visual homage to the tragedy and Ana Juan’s response a decade later. You will also hear from soldier and poet Brian Turner, whose haunting poem describes the challenges of a soldier returning from war to face the mundane realities of everyday life.

The America you will explore in this chapter is one marked by rapid change. Every decade seems to have brought sweeping technological, demographic, and cultural changes, defining and redefining America generation after generation.