Isabel V. Sawhill, from Pathways to the Middle Class: Balancing Personal and Public Responsibilities (2012)

Printed Pages 1521-1524from Pathways to the Middle Class

Balancing Personal and Public Responsibilities

Isabel V. Sawhill, Scott Winship, and Kerry Searle Grannis

Isabel V. Sawhill is codirector of the Center on Children and Families and the Budgeting for National Priorities Project at the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit public-policy organization based in Washington, D.C. Scott Winship is a fellow and research director at the Brookings Center’s Social Genome Project. Kelly Searle Grannis is the associate director of the Social Genome Project. The following excerpt is from the 2012 Social Genome Project of the Brookings Institution.

Findings

- The majority (61%) of Americans achieve the American Dream by reaching the middle class by middle age, but there are large gaps by race, gender, and children’s circumstances at birth.

- Success begets further success. Children who are successful at each life stage from early childhood to young adulthood are much more likely to achieve the American Dream.

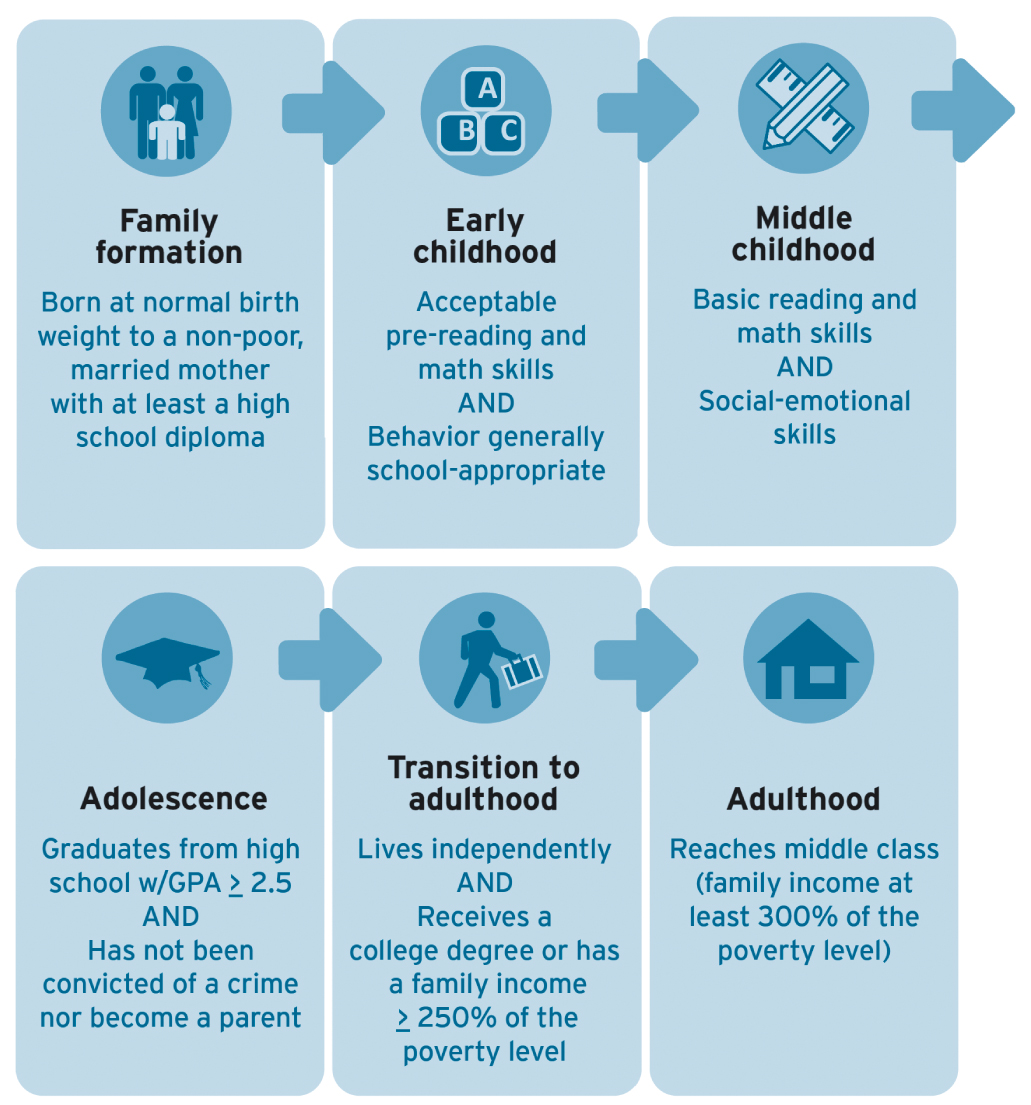

Figure 1

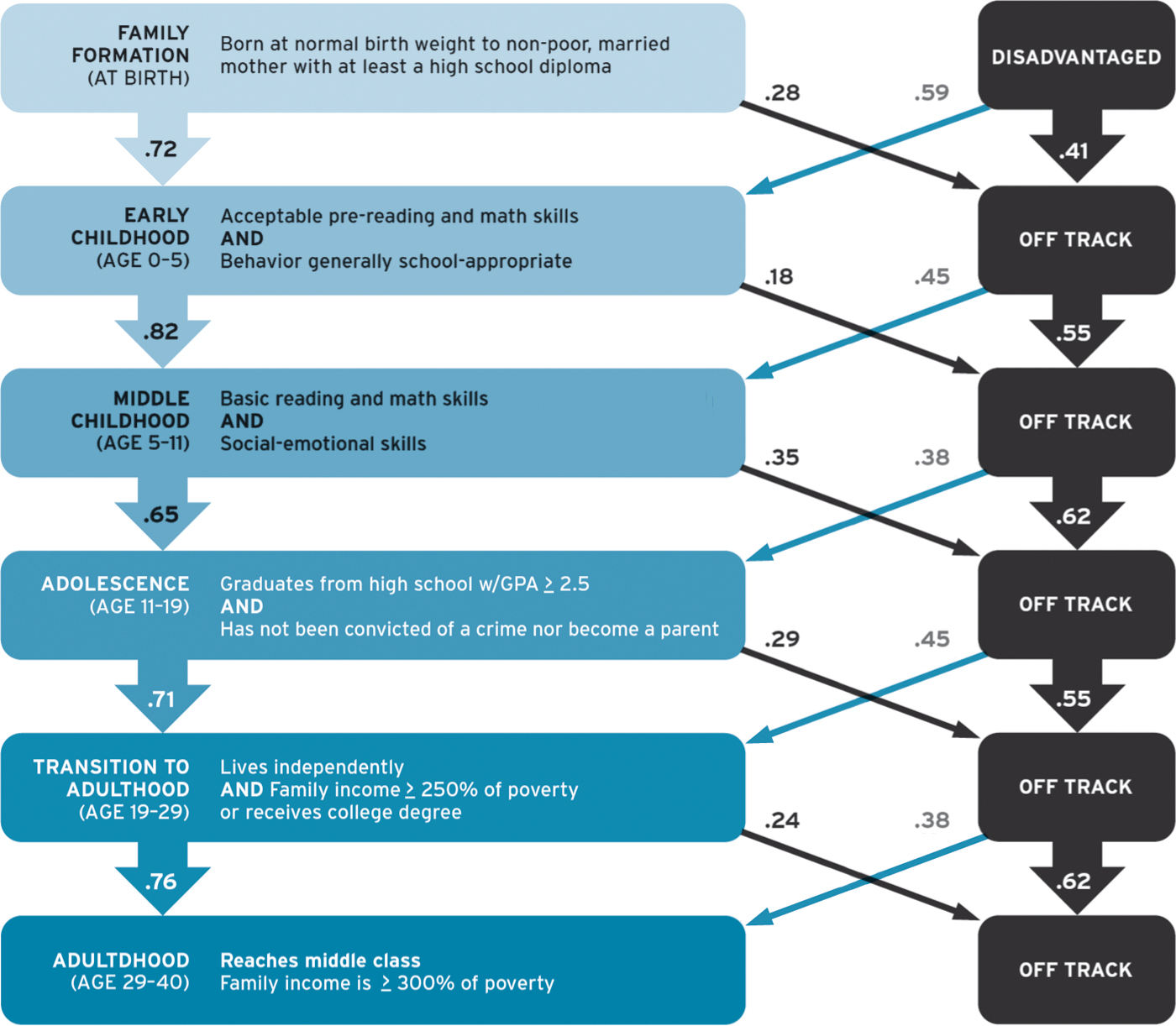

- Children from less advantaged families tend to fall behind at every stage. They are less likely to be ready for school at age 5 (59% vs 72%), to achieve core academic and social competencies at the end of elementary school (60% vs 77%), to graduate from high school with decent grades and no involvement with crime or teen pregnancy (41% vs 70%), and to graduate from college or achieve the equivalent income in their twenties (48% vs 70%).

- Racial gaps are large from the start and never narrow significantly, especially for African Americans, who trail by an average of 25 percentage points for the identified benchmarks.

- Girls travel through childhood doing better than boys only to find their prospects diminished during the adult years.

- The proportion of children who successfully navigate through adolescence is strikingly low: only 57%.

- For the small proportion of disadvantaged children who do succeed throughout school and early adulthood (17%), their chances of being middle class by middle age are almost as great as for their more advantaged peers (75% vs 83%).

Figure 2

- Keeping less advantaged children on track at each and every life stage is the right strategy for building a stronger middle class. Early interventions may prevent the need for later ones. As the data…make abundantly clear, success is a cumulative process. One-time interventions may not be enough to keep less advantaged children on track.

- It’s never too late to intervene—people who succeed in their twenties, despite earlier struggles, still have a good chance of making it to the middle class.

Recommendations

- Creating more opportunity will require a combination of greater personal responsibility and societal interventions that have proven effective at helping people climb the ladder. Neither alone is sufficient. Government does not raise children, parents do. But government can lend a helping hand.

- If one believes that good behavior and good policy must go hand in hand, programs should be designed to encourage personal responsibility and opportunity-enhancing behaviors.

- There are not just large, but widening gaps by socioeconomic status in family formation patterns, test scores, college-going, and adult earnings. These gaps should be addressed or the nation risks becoming increasingly divided over time.

- Budget cuts necessitated by the nation’s fiscal condition should discriminate between more and less effective programs. The evidence now exists to make these discriminations. Some programs actually save taxpayer money.

- Too little attention has been given to ensuring that more children are born to parents who are ready to raise a child. Unplanned pregnancies, abortions, and unwed births are way too high and childbearing within marriage is no longer the norm for women in their twenties, except among the college-educated. Government has a role to play here, but culture is at least as important.

- As many have noted, a high-quality preschool experience for less advantaged children and reform of K–12 schooling could not be more important.

- Increasing the number of young people who enroll in college is important, but increasing the proportion who actually graduate is critical. Graduation rates have lagged enrollment. A major problem is poor earlier preparation. In addition, disparities in ability to afford the cost of college mean that even equally qualified students from low- and high-income families do not have the same college-going opportunities.

(2012)