10.2 Conversion Disorder and Somatic Symptom Disorder

When a bodily ailment has an excessive and disproportionate impact on the person, has no apparent medical cause, or is inconsistent with known medical diseases, physicians may suspect a conversion disorder or a somatic symptom disorder. Consider the plight of Brian:

Brian was spending Saturday sailing with his wife, Helen. The water was rough but well within what they considered safe limits. They were having a wonderful time and really didn’t notice that the sky was getting darker, the wind blowing harder, and the sailboat becoming more difficult to control. After a few hours of sailing, they found themselves far from shore in the middle of a powerful and dangerous storm.

The storm intensified very quickly. Brian had trouble controlling the sailboat amidst the high winds and wild waves. He and Helen tried to put on the safety jackets they had neglected to wear earlier, but the boat turned over before they were finished. Brian, the better swimmer of the two, was able to swim back to the overturned sailboat, grab the side, and hold on for dear life, but Helen simply could not overcome the rough waves and reach the boat. As Brian watched in horror and disbelief, his wife disappeared from view.

After a time, the storm began to lose its strength. Brian managed to right the sailboat and sail back to shore. Finally he reached safety, but the personal consequences of this storm were just beginning. The next days were filled with pain and further horror: the Coast Guard finding Helen’s body … texts, emails, and conversations with family members and friends … self-

At first Brian and the hospital physician assumed that he must have been hurt during the accident. One by one, however, the hospital tests revealed nothing—

By the following morning, the weakness in his legs had become near paralysis. Because the physicians could not pin down the nature of his injuries, they decided to keep his activities to a minimum. He was not allowed to talk long with the police. To his deep regret, he was not even permitted to attend Helen’s funeral.

The mystery deepened over the following days and weeks. As Brian’s paralysis continued, he became more and more withdrawn, unable to see more than a few friends and family members and unable to take care of the many unpleasant tasks attached to Helen’s death. He could not bring himself to return to work or get on with his life. Texting, emailing, and phone conversations slowly came to a halt. At most, he was able to go online and surf the Internet. Almost from the beginning, Brian’s paralysis had left him self-

Conversion Disorder

Eventually, Brian received a diagnosis of conversion disorder (see Table 10-2). People with this disorder display physical symptoms that affect voluntary motor or sensory functioning, but the symptoms are inconsistent with known medical diseases (APA, 2013). In short, they have neurological-

conversion disorder A disorder in which a person’s bodily symptoms affect his or her voluntary motor and sensory functions, but the symptoms are inconsistent with known medical diseases.

conversion disorder A disorder in which a person’s bodily symptoms affect his or her voluntary motor and sensory functions, but the symptoms are inconsistent with known medical diseases.

|

Conversion Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Presence of at least one symptom or deficit that affects voluntary or sensory function. |

|

2. |

Symptoms are found to be inconsistent with known neurological or medical disease. |

|

3. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

Conversion disorder often is hard, even for physicians, to distinguish from a genuine medical problem (Dandachi-

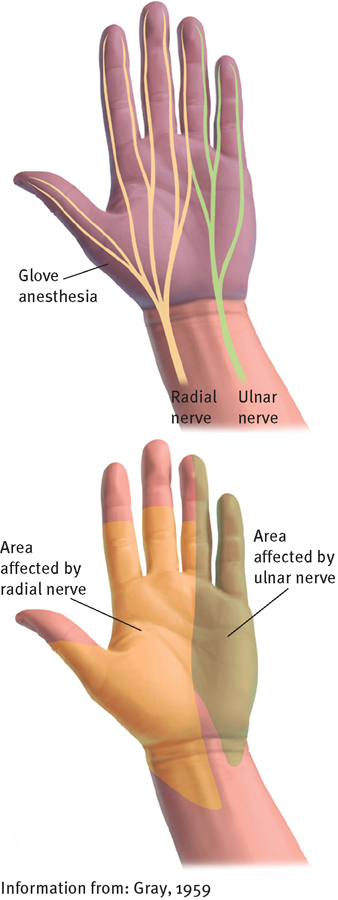

Glove anesthesia

In this conversion symptom (top figure) the entire hand, extending from the fingertips to the wrist, becomes numb. Actual physical damage (bottom figure) to the ulnar nerve, in contrast, causes anesthesia in the ring finger and little finger and beyond the wrist partway up the arm; damage to the radial nerve causes loss of feeling only in parts of the ring, middle, and index fingers and the thumb and partway up the arm.

The physical effects of a conversion disorder may also differ from those of the corresponding medical problem (Scheidt et al., 2014; Dandachi-

Unlike people with factitious disorder, those with conversion disorder do not consciously want or purposely produce their symptoms. Like Brian, they almost always believe that their problems are genuinely medical (Lahman et al., 2010). This pattern is called “conversion” disorder because clinical theorists used to believe that individuals with the disorder are converting psychological needs or conflicts into their neurological-

Conversion disorder usually begins between late childhood and young adulthood; it is diagnosed at least twice as often in women as in men (Raj et al., 2014). It typically appears suddenly, at times of extreme stress, and lasts a matter of weeks (Kukla et al., 2010). Some research suggests that people who develop the disorder tend to be generally suggestible (see MindTech below); many are highly susceptible to hypnotic procedures, for example (Parish & Yutzy, 2011; Roelofs et al., 2002). It is thought to be a rare problem, occurring in at most 5 of every 1,000 persons.

MindTech

Can Social Media Spread “Mass Hysteria”?

In Chapter 1, you read about outbreaks during the Middle Ages of mass madness, also called mass hysteria or mass psychogenic illness, in which large numbers of people would share psychological or physical maladies that had no apparent cause (see pages 10–

New Zealand sociologist Robert Bartholemew (2013) has been studying mass psychogenic illnesses that date back over 400 years, and he argues that social media is a major factor in the current increase. One notable 2011 outbreak in Le Roy, New York, demonstrates the suggestive role played by social media (Vitelli, 2013; Dominus, 2012). A local high school student began having facial spasms. After several weeks, others started having similar symptoms, and eventually 18 girls from the high school were affected. Apparently, a number of these teenagers began to show symptoms after they saw a YouTube video featuring a girl from a nearby town who had significant tics. Doctors eventually concluded that this was an example of mass psychogenic illness.

An unusual aspect of the Le Roy case that further points to the likely role of social media is that in addition to the 18 high school girls, a 36-

In what ways could social media itself help to prevent or reduce cases of mass psychogenic illness?

This case mirrors others in recent years, such as an outbreak of hiccups and vocal tics in early 2013 among teenagers in Danvers, Massachusetts, and the case of 400 garment workers in a Bangladesh factory who had severe gastrointestinal symptoms for which there was ultimately no physical explanation (Vitelli, 2013). In these and other cases, the symptoms seemed to be spread, at least in part, by social media exposure.

Bartholomew (2014) estimates that that these are but a few examples of hundreds of cases that occur in the United States alone each year. Moreover, he strongly believes that due to the power of social media, future outbreaks may be more numerous, wide ranging, and severe than any yet recorded. He notes that there is the “potential for a far greater or global episode, unless we quickly understand how social media is, for the first time, acting as the primary … agent of spread for conversion disorder.” As he points out, in the distant past “the local priests, who were … summoned to [treat mass psychogenic illnesses], faced a daunting task … but they were fortunate in one regard: they did not have to contend with mobile phones, Twitter, and Facebook.” ![]()

Somatic Symptom Disorder

People with somatic symptom disorder become excessively distressed, concerned, and anxious about bodily symptoms that they are experiencing, and their lives are greatly disrupted by the symptoms (APA, 2013) (see Table 10-3). The symptoms last longer but are less dramatic than those found in conversion disorder. In some cases, the somatic symptoms have no known cause; in others, the cause can be identified. Either way, the person’s concerns are disproportionate to the seriousness of the bodily problems.

somatic symptom disorder A disorder in which people become excessively distressed, concerned, and anxious about bodily symptoms that they are experiencing, and their lives are greatly and disproportionately disrupted by the symptoms.

somatic symptom disorder A disorder in which people become excessively distressed, concerned, and anxious about bodily symptoms that they are experiencing, and their lives are greatly and disproportionately disrupted by the symptoms.

|

Somatic Symptom Disorder |

||

|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Person experiences at least one upsetting or repeatedly disruptive physical (somatic) symptom. |

|

|

2. |

Person experiences an unreasonable number of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors regarding the nature or implications of the physical symptoms, including one of the following: |

|

|

|

(a) |

Repeated, excessive thoughts about their seriousness. |

|

|

(b) |

Continual high anxiety about their nature or health implications. |

|

|

(c) |

Disproportionate amounts of time and energy spent on the symptoms or their health implications. |

|

3. |

Physical symptoms usually continue to some degree for more than 6 months. |

|

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

||

Two patterns of somatic symptom disorder have received particular attention. In one, sometimes called a somatization pattern, the individual experiences a large and varied number of bodily symptoms. In the other, called a predominant pain pattern, the person’s primary bodily problem is the experience of pain.

Somatization PatternSheila baffled medical specialists with the wide range of her symptoms:

Sheila reported having abdominal pain since age 17, necessitating exploratory surgery that yielded no specific diagnosis. She had several pregnancies, each with severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain; she ultimately had a hysterectomy for a “tipped uterus.” Since age 40 she had experienced dizziness and “blackouts,” which she eventually was told might be multiple sclerosis or a brain tumor. She continued to be bedridden for extended periods of time, with weakness, blurred vision, and difficulty urinating. At age 43 she was worked up for a hiatal hernia because of complaints of bloating and intolerance of a variety of foods. She also had additional hospitalizations for neurological, hypertensive, and renal workups, all of which failed to reveal a definitive diagnosis.

(Spitzer et al., 1994, 1981, pp. 185, 260)

Like Sheila, people with a somatization pattern of somatic symptom disorder experience many long-

People with a somatization pattern usually go from doctor to doctor in search of relief. They often describe their many symptoms in dramatic and exaggerated terms. Most also feel anxious and depressed (Dimsdale & Creed, 2010; Leiknes, Finset, & Moum, 2010). The pattern typically lasts for many years, fluctuating over time but rarely disappearing completely without therapy (Parish & Yutzy, 2011; Abbey, 2005).

Between 0.2 and 2.0 percent of all women in the United States may experience a somatization pattern in any given year, compared with less than 0.2 percent of men (North, 2005; APA, 2000). The pattern often runs in families; as many as 20 percent of the close female relatives of women with the pattern also develop it. It usually begins between adolescence and young adulthood.

Predominant Pain PatternIf the primary feature of somatic symptom disorder is pain, the person is said to have a predominant pain pattern. Patients with conversion disorder or another pattern of somatic symptom disorder may also experience pain, but it is the key symptom in this pattern. The source of the pain may be known or unknown. Either way, the concerns and disruption produced by the pain are disproportionate to its severity and seriousness.

Although the precise prevalence has not been determined, this pattern appears to be fairly common (Nickel et al., 2010). It may begin at any age, and women seem more likely than men to experience it (APA, 2000). Often it develops after an accident or during an illness that has caused genuine pain, which then takes on a life of its own. For example, Laura, a 36-

Before the operation I would have little joint pains, nothing that really bothered me that much. After the operation I was having severe pains in my chest and in my ribs, and those were the type of problems I’d been having after the operation, that I didn’t have before…. I’d go to an emergency room at night, 11:00, 12:00, 1:00 or so. I’d take the medicine, and the next day it stopped hurting, and I’d go back again. In the meantime this is when I went to the other doctors, to complain about the same thing, to find out what was wrong; and they could never find out what was wrong with me either….

… At certain points when I go out or my husband and I go out, we have to leave early because I start hurting…. A lot of times I just won’t do things because my chest is hurting for one reason or another…. Two months ago when the doctor checked me and another doctor looked at the x-

(Green, 1985, pp. 60–

What Causes Conversion and Somatic Symptom Disorders?

For many years, conversion and somatic symptom disorders were referred to as hysterical disorders. This label was meant to convey the prevailing belief that excessive and uncontrolled emotions underlie the bodily symptoms found in these disorders.

Work by Ambroise-

Why do the terms “hysteria” and “hysterical” currently have such negative connotations in our society, as in “mass hysteria” and “hysterical personality”?

Today’s leading explanations for conversion and somatic symptom disorders come from the psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and multicultural models. None has received much research support, however, and the disorders are still poorly understood.

The Psychodynamic ViewAs you read in Chapter 1, Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis began with his efforts to explain hysterical symptoms. Indeed, he was one of the few clinicians of his day to treat patients with these symptoms seriously, as people with genuine problems. After studying hypnosis in Paris, Freud became interested in the work of an older physician, Josef Breuer (1842–

Observing that most of his patients with hysterical disorders were women, Freud centered his explanation of such disorders on the needs of girls during their phallic stage (ages 3 through 5). At that time in life, he believed, all girls develop a pattern of desires called the Electra complex: each girl experiences sexual feelings for her father and at the same time recognizes that she must compete with her mother for his affection. However, aware of her mother’s more powerful position and of cultural taboos, the child typically represses her sexual feelings and rejects these early desires for her father.

Freud believed that if a child’s parents overreact to her sexual feelings—

Most of today’s psychodynamic theorists take issue with parts of Freud’s explanation of conversion and somatic symptom disorders (Nickel et al., 2010), but they continue to believe that sufferers of the disorders have unconscious conflicts carried forth from childhood, which arouse anxiety, and that the they convert this anxiety into “more tolerable” physical symptoms (Brown et al., 2005).

Psychodynamic theorists propose that two mechanisms are at work in these disorders—

primary gain In psychodynamic theory, the gain people derive when their somatic symptoms keep their internal conflicts out of awareness.

primary gain In psychodynamic theory, the gain people derive when their somatic symptoms keep their internal conflicts out of awareness.

secondary gain In psychodynamic theory, the gain people derive when their somatic symptoms elicit kindness from others or provide an excuse to avoid unpleasant activities.

secondary gain In psychodynamic theory, the gain people derive when their somatic symptoms elicit kindness from others or provide an excuse to avoid unpleasant activities.

The Behavioral ViewBehavioral theorists propose that the physical symptoms of conversion and somatic symptom disorders bring rewards to sufferers (see Table 10-4). Perhaps the symptoms remove those with the disorders from an unpleasant relationship or perhaps the symptoms bring attention from other people (Witthöft & Hiller, 2010). In response to such rewards, the sufferers learn to display the bodily symptoms more and more prominently. Behaviorists also hold that people who are familiar with an illness will more readily adopt its physical symptoms. In fact, studies find that many sufferers develop their bodily symptoms after they or their close relatives or friends have had similar medical problems (Marshall et al., 2007).

|

Disorder |

Voluntary Control of Symptoms? |

Symptoms Linked to Psychosocial Factor? |

An Apparent Goal? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Malingering |

Yes |

Maybe |

Yes |

|

Factitious disorder |

Yes |

Yes |

No* |

|

Conversion disorder |

No |

Yes |

Maybe |

|

Somatic symptom disorder |

No |

Yes |

Maybe |

|

Illness anxiety disorder |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Psychophysiological disorder |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Physical illness |

No |

Maybe |

No |

|

* Except for medical attention. |

|||

Clearly, the behavioral focus on the role of rewards is similar to the psychodynamic notion of secondary gain. The key difference is that psychodynamic theorists view the gains as indeed secondary—

Like the psychodynamic explanation, the behavioral view of conversion and somatic symptom disorders has received little research support. Even clinical case reports only occasionally support this position. In many cases the pain and upset that surround the disorders seem to outweigh any rewards the symptoms might bring.

DSM-5 CONTROVERSY

Overreactions to Medical Illnesses?

According to DSM-

The Cognitive ViewSome cognitive theorists propose that conversion and somatic symptom disorders are forms of communication, providing a means for people to express emotions that would otherwise be difficult to convey (Hallquist et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2005). Like their psychodynamic colleagues, these theorists hold that the emotions of people with the disorders are being converted into physical symptoms. They suggest, however, that the purpose of the conversion is not to defend against anxiety but to communicate extreme feelings—

According to this view, people who find it particularly hard to recognize or express their emotions are candidates for conversion and somatic symptom disorders. So are those who “know” the language of physical symptoms through firsthand experience with a genuine physical ailment. Because children are less able to express their emotions verbally, they are particularly likely to develop physical symptoms as a form of communication (Shaw et al., 2010). Like the other explanations, this cognitive view has not been widely tested or supported by research.

The Multicultural ViewMost Western clinicians believe that it is inappropriate to produce or focus excessively on somatic symptoms in response to personal distress (Shaw et al., 2010; So, 2008; Escobar, 2004). That is, in part, why conversion and somatic symptom disorders are included in DSM-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Diagnostic Confusion

Many medical problems with vague or confusing symptoms—

In fact, the transformation of personal distress into somatic complaints is the norm in many non-

The lesson to be learned from such multicultural findings is not that somatic reactions to stress are superior to psychological ones or vice versa, but rather, once again, that both bodily and psychological reactions to life events are often influenced by one’s culture. Overlooking this point can lead to knee-

How Are Conversion and Somatic Symptom Disorders Treated?

People with conversion and somatic symptom disorders usually seek psychotherapy only as a last resort. They believe that their problems are completely medical and at first reject all suggestions to the contrary (Lahmann et al., 2010). When a physician tells them that their symptoms or concerns have a psychological dimension, they often go to another physician. Eventually, however, many patients with these disorders do consent to psychotherapy, psychotropic drug therapy, or both (Raj et al., 2014).

Many therapists focus on the causes of these disorders (the trauma or anxiety tied to the physical symptoms) and apply insight, exposure, and drug therapies (Boone, 2011). Psychodynamic therapists, for example, try to help those with somatic symptoms become conscious of and resolve their underlying fears, thus eliminating the need to convert anxiety into physical symptoms (Nickel et al., 2010; Hawkins, 2004). Behavioral therapists use exposure treatments. They expose clients to features of the horrific events that first triggered their physical symptoms, expecting that the clients will become less anxious over the course of repeated exposures and more able to face those upsetting events directly rather than through physical channels (Stuart et al., 2008). And biological therapists use antianxiety drugs or certain anti-

Other therapists try to address the physical symptoms of these disorders rather than the causes, using techniques such as suggestion, reinforcement, or confrontation (Parish & Yutzy, 2011). Those who employ suggestion offer emotional support to patients and tell them persuasively (or hypnotically) that their physical symptoms will soon disappear (Hallquist et al., 2010; Lahmann et al., 2010). Therapists who take a reinforcement approach arrange for the removal of rewards for a client’s “sickness” symptoms and an increase of rewards for healthy behaviors (Raj et al., 2014; North, 2005). And therapists who take a confrontational approach try to force patients out of the sick role by straightforwardly telling them that their bodily symptoms are without medical basis (Sjolie, 2002). Researchers have not fully evaluated the effects of these particular approaches on conversion and somatic symptom disorders (Martlew, Pulman, & Marson, 2014; Boone, 2011).