11.1 Anorexia Nervosa

Shani, 15 years old and in the ninth grade, displays many symptoms of anorexia nervosa (APA, 2013). She purposely maintains a significantly low body weight, intensely fears becoming overweight, has a distorted view of her weight and shape, and is excessively influenced by her weight and shape in her self-

anorexia nervosa A disorder marked by the pursuit of extreme thinness and by extreme weight loss.

anorexia nervosa A disorder marked by the pursuit of extreme thinness and by extreme weight loss.

|

Anorexia Nervosa |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual purposely takes in too little nourishment, resulting in body weight that is very low and below that of other people of similar age and gender. |

|

2. |

Individual is very fearful of gaining weight, or repeatedly seeks to prevent weight gain despite low body weight. |

|

3. |

Individual has a distorted body perception, places inappropriate emphasis on weight or shape in judgments of herself or himself, or fails to appreciate the serious implications of her or his low weight. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Like Shani, at least half of the people with anorexia nervosa reduce their weight by restricting their intake of food, a pattern called restricting-

Ninety to 95 percent of all cases of anorexia nervosa occur in females. Although the disorder can appear at any age, the peak age of onset is between 14 and 20 years. Between 0.5 and 4.0 percent of all females in Western countries develop the disorder in their lifetime, and many more display at least some of its symptoms (Ekern, 2014; Smink et al., 2013; Stice et al., 2013). It seems to be on the increase in North America, Europe, and Japan.

Typically the disorder begins after a person who is slightly overweight or of normal weight has been on a diet (Stice & Presnell, 2010). The escalation toward anorexia nervosa may follow a stressful event such as separation of parents, a move away from home, or an experience of personal failure (Wilson et al., 2003). Although most people with the disorder recover, between 2 and 6 percent of them become so seriously ill that they die, usually from medical problems brought about by starvation, or from suicide (Suokas et al., 2013; Forcano et al., 2010).

The Clinical Picture

Becoming thin is the key goal for people with anorexia nervosa, but fear provides their motivation. People with this disorder are afraid of becoming obese, of giving in to their growing desire to eat, and more generally of losing control over the size and shape of their bodies. In addition, despite their focus on thinness and the severe restrictions they may place on their food intake, people with anorexia are preoccupied with food. They may spend considerable time thinking and even reading about food and planning their limited meals (Herzig, 2004). Many report that their dreams are filled with images of food and eating (Knudson, 2006).

This preoccupation with food may in fact be a result of food deprivation rather than its cause. In a famous “starvation study” conducted in the late 1940s, 36 normal-

Persons with anorexia nervosa also think in distorted ways. They usually have a low opinion of their body shape, for example, and consider themselves unattractive (Boone et al., 2014; Siep et al., 2011). In addition, they are likely to overestimate their actual proportions. While most women in Western society overestimate their body size, the estimates of those with anorexia nervosa are particularly high. In one of her classic books on eating disorders, Hilde Bruch, a pioneer in this field, recalled the self-

I look in a full-

(Bruch, 1973)

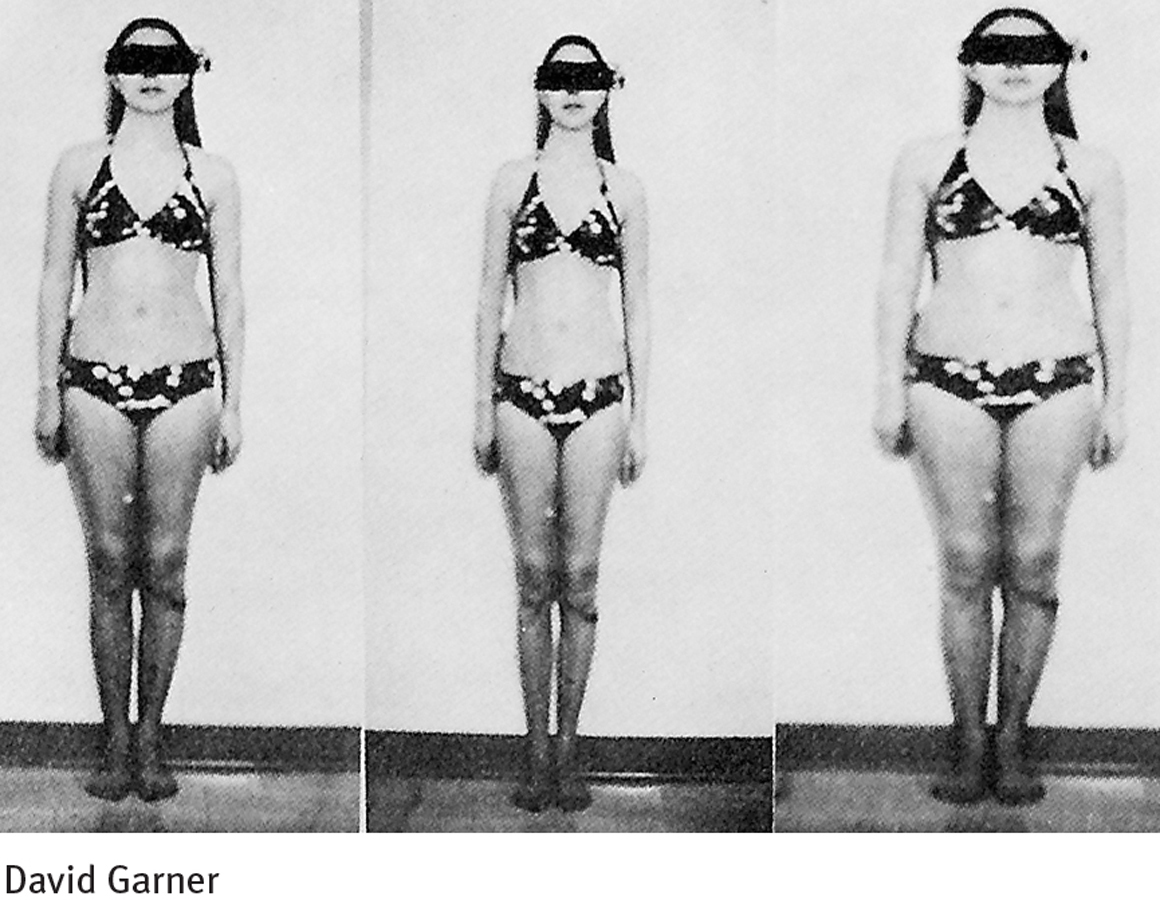

This tendency to overestimate body size has been tested in the laboratory (Delinsky, 2011; Farrell, Lee, & Shafran, 2005). In a popular assessment technique, research participants look at a photograph of themselves through an adjustable lens. They are asked to adjust the lens until the image that they see matches their actual body size. The image can be made to vary from 20 percent thinner to 20 percent larger than actual appearance. In one study, more than half of the individuals with anorexia nervosa overestimated their body size, stopping the lens when the image was larger than they actually were.

The distorted thinking of anorexia nervosa also takes the form of certain maladaptive attitudes and misperceptions (Alvarenga et al., 2014; Fairburn et al., 2008). Sufferers tend to hold such beliefs as “I must be perfect in every way”; “I will become a better person if I deprive myself “; and “I can avoid guilt by not eating.”

People with anorexia nervosa also have certain psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, low self-

Medical Problems

The starvation habits of anorexia nervosa cause medical problems (Faje et al., 2014; Suokas et al., 2014; Oflaz et al., 2013). Women develop amenorrhea, the absence of menstrual cycles. Other problems include lowered body temperature, low blood pressure, body swelling, reduced bone mineral density, and slow heart rate. Metabolic and electrolyte imbalances also may occur and can lead to death by heart failure or circulatory collapse. The poor nutrition of people with anorexia nervosa may also cause skin to become rough, dry, and cracked; nails to become brittle; and hands and feet to be cold and blue. Some people lose hair from the scalp, and some grow lanugo (the fine, silky hair that covers some newborns) on their trunk, extremities, and face. Shani, the young woman whose self-

amenorrhea The absence of menstrual cycles.

amenorrhea The absence of menstrual cycles.

Nobody knew that I was always cold no matter how many layers I wore. And that my hair came out in thick wads whenever I wet it or washed it. That I stopped menstruating. That at night I lay awake agonizing over thoughts of the day’s consumption. That the guilt I carried every day weighed on me like lead. That my hipbones hurt to lie on my stomach and my coccyx hurt to sit on the floor. And that the concave feeling in my stomach of dying hunger left in its place an anger that would destroy all feeling.

(Raviv, 2010)