Treatments for Anorexia Nervosa

The immediate aims of treatment for anorexia nervosa are to help people regain their lost weight, recover from malnourishment, and eat normally again. Therapists must then help them to make psychological and perhaps family changes to lock in those gains.

Page 370

How Are Proper Weight and Normal Eating Restored?A variety of treatment methods are used to help patients with anorexia nervosa gain weight quickly and return to health within weeks. In the past, treatment almost always took place in a hospital, but now it is often offered in day hospitals or outpatient settings (Raveneau et al., 2014; Keel & McCormick, 2010).

In life-threatening cases, clinicians may need to force tube and intravenous feedings on a patient who refuses to eat (Touyz & Carney, 2010; Tyre, 2005). Unfortunately, this use of force may cause the client to distrust the clinician. In contrast, clinicians using behavioral weight-restoration approaches offer rewards whenever patients eat properly or gain weight and offer no rewards when they eat improperly or fail to gain weight (Tacón & Caldera, 2001).

Perhaps the most popular weight-restoration technique in recent years has been a combination of supportive nursing care, nutritional counseling, and a relatively high-calorie diet—often called a nutritional rehabilitation program (Leclerc et al., 2013; Hart & Abraham, 2011; Croll, 2010). Here nurses gradually increase a patient’s diet over the course of several weeks, to more than 3,000 calories a day (Zerbe, 2010, 2008; Herzog et al., 2004). The nurses educate patients about the program, track their progress, provide encouragement, and help them recognize that their weight gain is under control and will not lead to obesity. In some programs, the nurses also use motivational interviewing, an intervention in which they motivate clients to actively make and follow through on constructive choices regarding their eating behaviors and their lives (Dray et al., 2014). Studies find that patients in nursing-care programs usually gain the necessary weight over 8 to 12 weeks.

A healthier look Runway models have their makeup finalized just before the start of Fashion Week in New York City in 2012. Fashion Week is always a special event in the industry, but was particularly so that year, because the 19 editors of Vogue magazines around the world made a pact to henceforth project the image of “healthy” models. They agreed to stop hiring models who are under the age of 16 or who appear to have an eating disorder—for fashion shows, ad campaigns, or photo shoots.

How Are Lasting Changes Achieved?Clinical researchers have found that people with anorexia nervosa must overcome their underlying psychological problems in order to create lasting improvement. Therapists typically use a combination of education, psychotherapy, and family therapy to help reach this broader goal (Wade & Watson, 2012; Zerbe, 2010, 2008). Psychotropic drugs have also been helpful in some cases, but research has found that such medications are typically of limited benefit over the long-term course of anorexia nervosa (Starr & Kreipe, 2014; David et al., 2011).

COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPYA combination of behavioral and cognitive interventions are included in most treatment programs for anorexia nervosa. Such techniques are designed to help clients appreciate and alter the behaviors and thought processes that help keep their restrictive eating going (Fairburn & Cooper, 2014; Evans & Waller, 2011; Murphy et al., 2010). On the behavioral side, clients are typically required to monitor (perhaps by keeping a diary) their feelings, hunger levels, and food intake and the ties between these variables. On the cognitive side, they are taught to identify their “core pathology”—the deep-seated belief that they should in fact be judged by their shape and weight and by their ability to control these physical characteristics. The clients may also be taught alternative ways of coping with stress and of solving problems.

The therapists who use these approaches are particularly careful to help patients with anorexia nervosa recognize their need for independence and teach them more appropriate ways to exercise control (Pike et al., 2010). The therapists may also teach them to identify better and trust their internal sensations and feelings (Wilson, 2010; Fairburn et al., 2008). In the following session, a therapist tries to help a 15-year-old client recognize and share her feelings:

Page 371

BETWEEN THE LINES

When it comes to eating disorders, teasing is no laughing matter (Hilbert et al., 2013; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007). In one study, researchers found that adolescents who were teased about their weight by family members were twice as likely as nonteased teens of similar weight to become overweight within five years and 1.5 times more likely to become binge eaters and use extreme weight control measures.

|

|

I don’t talk about my feelings; I never did. |

|

|

Do you think I’ll respond like others? |

|

|

|

|

|

I think you may be afraid that I won’t pay close attention to what you feel inside, or that I’ll tell you not to feel the way you do—that it’s foolish to feel frightened, to feel fat, to doubt yourself, considering how well you do in school, how you’re appreciated by teachers, how pretty you are. |

|

|

(Looking somewhat tense and agitated) Well, I was always told to be polite and respect other people, just like a stupid, faceless doll. (Affecting a vacant, doll-like pose) |

|

|

Do I give you the impression that it would be disrespectful for you to share your feelings, whatever they may be? |

|

|

Not really; I don’t know. |

|

|

I can’t, and won’t, tell you that this is easy for you to do…. But I can promise you that you are free to speak your mind, and that I won’t turn away. |

(Strober & Yager, 1985, pp. 368–369) |

Finally, cognitive-behavioral therapists help clients with anorexia nervosa change their attitudes about eating and weight (Fairburn & Cooper, 2014; Evans & Waller, 2012; Pike et al., 2010) (see Table 11-4). The therapists may guide clients to identify, challenge, and change maladaptive assumptions, such as “I must always be perfect” or “My weight and shape determine my value” (Fairburn et al., 2008; Lask & Bryant-Waugh, 2000). They may also educate clients about the body distortions typical of anorexia nervosa and help them see that their own assessments of their size are incorrect. Even if a client never learns to judge her body shape accurately, she may at least reach a point where she says, “I know that a key feature of anorexia nervosa is a misperception of my own size, so I can expect to feel fat regardless of my actual size.”

Table 11.4: table: 11-4Sample Items from the Eating Disorder Inventory

For each item, decide if the item is true about you ALWAYS (A), USUALLY (U), OFTEN (O), SOMETIMES (S), RARELY (R), or NEVER (N). Circle the letter that corresponds to your rating. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I stuff myself with food. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I think that my thighs are too large. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I feel extremely guilty after overeating. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am terrified of gaining weight. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I get confused as to whether or not I am hungry. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have the thought of trying to vomit in order to lose weight. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I think my buttocks are too large. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I eat or drink in secrecy. |

(Information from: Clausen et al., 2011; Garner, 2005; Garner, Olmsted, & Polivy, 1991, 1984.) |

Page 372

Although cognitive-behavioral techniques are often of great help to clients with anorexia nervosa, research suggests that the techniques typically must be supplemented by other approaches to bring about better results (Zerbe, 2010, 2008). Family therapy, for example, is often included in treatment.

Calling for more assertive action According to many people, efforts to change the negative impact of the fashion industry and media on women have been woefully ineffective to date. Thus a feminist movement has emerged to more aggressively fight society’s “obsession with female thinness.” The movement’s slogan, “Riots Not Diets,” has already caught fire and now adorns bags, T-shirts, patches, cookies, glassware, and many other objects around the world.

CHANGING FAMILY INTERACTIONSFamily therapy can be an invaluable part of treatment for anorexia nervosa, particularly for children and adolescents with the disorder. As in other family therapy situations, the therapist meets with the family as a whole, points out troublesome family patterns, and helps the members make appropriate changes. In particular, family therapists may try to help the person with anorexia nervosa separate her feelings and needs from those of other members of her family. Although the role of family in the development of anorexia nervosa is not yet clear, research strongly suggests that family therapy (or at least parent counseling) can be helpful in the treatment of this disorder (Ambresin et al., 2014; Hoste et al., 2012; Lock, 2011; Zucker et al., 2011).

|

|

I think I know what [Susan] is going through: all the doubt and insecurity of growing up and establishing her own identity. (Turning to the patient, with tears) If you just place trust in yourself, with the support of those around you who care, everything will turn out for the better. |

|

|

Are you making yourself available to her? Should she turn to you, rely on you for guidance and emotional support? |

|

|

Well, that’s what parents are for. |

|

|

(Turning to patient) What do you think? |

|

|

(To mother) I can’t keep depending on you, Mom, or everyone else. That’s what I’ve been doing, and it gave me anorexia…. |

|

|

Do you think your mom would prefer that there be no secrets between her and the kids—an open door, so to speak? |

|

|

|

|

|

(To patient and younger sister) How about you two? |

|

|

Yeah. Sometimes it’s like whatever I feel, she has to feel. |

|

|

|

(Strober & Yager, 1985, pp. 381–382) |

What Is the Aftermath of Anorexia Nervosa?The use of combined treatment approaches has greatly improved the outlook for people with anorexia nervosa, although the road to recovery can be difficult. The course and outcome of this disorder vary from person to person, but researchers have noted certain trends.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In 1968, the average fashion model was 8 percent thinner than the typical woman. Today, models are 23 percent thinner (Tashakova, 2011; Derenne & Beresin, 2006).

On the positive side, weight is often quickly restored once treatment for the disorder begins (McDermott & Jaffa, 2005), and treatment gains may continue for years (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Haliburn, 2005). As many as 85 percent of patients continue to show improvement—either full or partial—when they are interviewed several years or more after their initial recovery (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Brewerton & Costin, 2011; van Son et al., 2010).

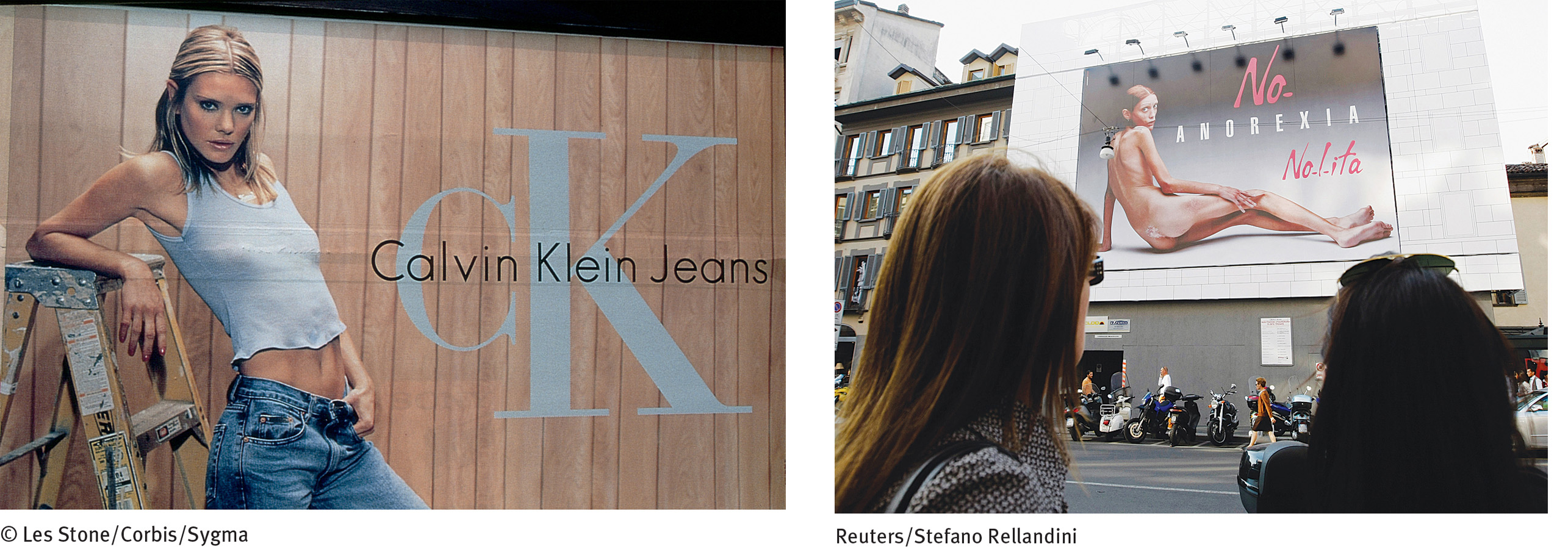

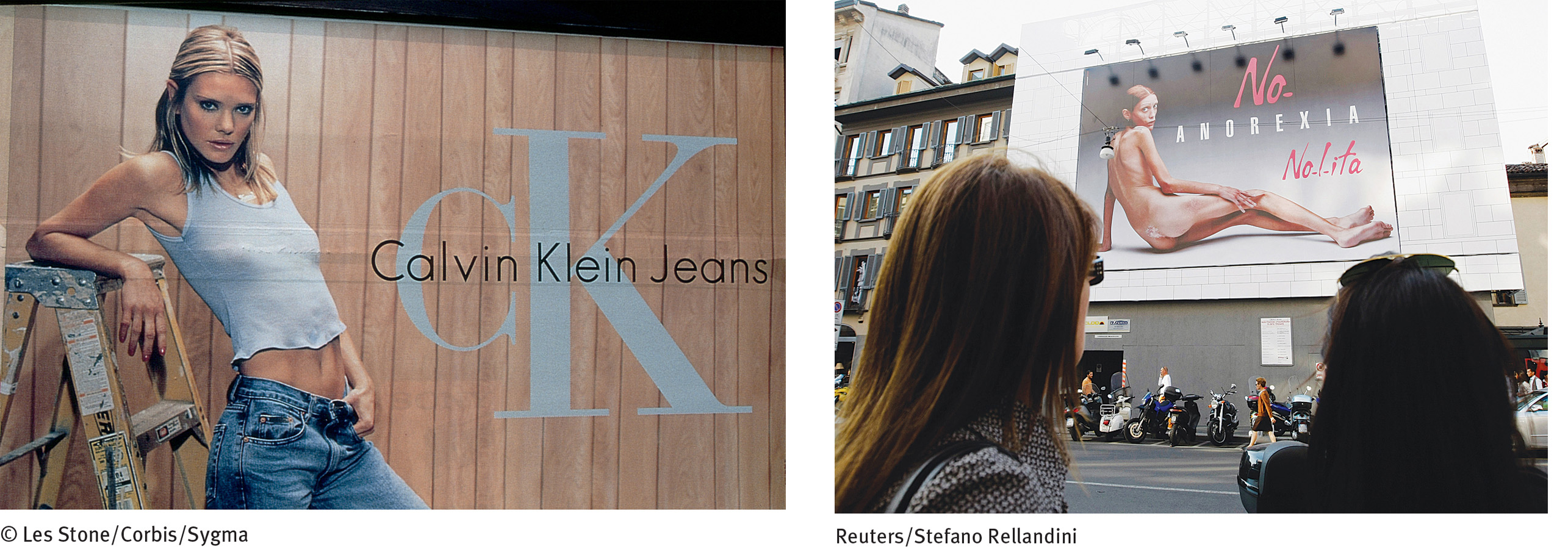

A story of two billboards In 1995, the Calvin Klein clothing brand posed young teenagers in sexually suggestive clothing ads (left). A public uproar forced the company to remove the ads from magazines and billboards across the United States, but by then, a point had been made—that extreme thinness was in vogue for female fashion and, indeed, for females of all ages. In contrast, the Nolita clothing brand launched a major ad campaign against excessive thinness in 2007, displaying anti-anorexia billboards throughout Italy (right). Here two young women stare at one such billboard—that of an emaciated naked woman appearing beneath the words “No Anorexia.” The billboard model, Isabelle Caro, died in 2010 of complications from anorexia nervosa.

Another positive note is that most females with anorexia nervosa menstruate again when they regain their weight, and other medical improvements follow (Mitchell & Crow, 2010; Zerbe, 2008). Also encouraging is that the death rate from anorexia nervosa seems to be falling (van Son et al., 2010). Earlier diagnosis and safer and faster weight-restoration techniques may account for this trend. Deaths that do occur are usually caused by suicide, starvation, infection, gastrointestinal problems, or electrolyte imbalance.

Page 373

On the negative side, as many as 25 percent of persons with anorexia nervosa remain seriously troubled for years (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Steinhausen, 2009). Furthermore, recovery, when it does occur, is not always permanent. At least one-third of recovered patients have recurrences of anorexic behavior, usually triggered by new stresses, such as marriage, pregnancy, or a major relocation (Stice et al., 2013; Eifert et al., 2007; Fennig et al., 2002). Even years later, many who have recovered continue to express concerns about their weight and appearance. Some still restrict their diets to a degree, feel anxiety when they eat with other people, or hold some distorted ideas about food, eating, and weight (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Fairburn et al., 2008).

About half of those who have suffered from anorexia nervosa continue to have certain emotional problems—particularly depression, obsessiveness, and social anxiety—years after treatment. Such problems are particularly common in those who had not reached a fully normal weight by the end of treatment (Bodell & Mayer, 2011; Steinhausen, 2002).

The more weight persons have lost and the more time that passes before they enter treatment, the poorer the recovery rate (Fairburn et al., 2008). People who had psychological or sexual problems before the onset of the disorder tend to have a poorer recovery rate than those without such a history (Amianto et al., 2011; Finfgeld, 2002). People whose families are dysfunctional have less positive treatment outcomes (Holtom-Viesel & Allan, 2014). Teenagers seem to have a better recovery rate than older patients (Richard, 2005; Steinhausen et al., 2000).

Treatments for Bulimia Nervosa

Treatment programs for bulimia nervosa are often offered in eating disorder clinics (Henderson et al., 2014). Such programs share the immediate goals of helping clients to eliminate their binge-purge patterns and establish good eating habits and the more general goal of eliminating the underlying causes of bulimic patterns. The programs emphasize education as much as therapy (Fairburn & Cooper, 2014; Zerbe, 2010, 2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy is particularly helpful in cases of bulimia nervosa—perhaps even more helpful than in cases of anorexia nervosa (Fairburn & Cooper, 2014; Wonderlich et al., 2014). And antidepressant drug therapy, which is of limited help to people with anorexia nervosa, appears to be quite effective in many cases of bulimia nervosa (Starr & Kreipe, 2014; David et al., 2011).

Page 374

BETWEEN THE LINES

Smoking, Eating, and Weight

Smokers weigh less than nonsmokers.

75 percent of people who quit smoking gain weight.

Nicotine, a stimulant substance, suppresses appetites and increases metabolic rate, perhaps because of its impact on the lateral hypothalamus.

(Information from: Kroemer et al., 2013; Higgins & George, 2007)

Cognitive-Behavioral TherapyWhen treating clients with bulimia nervosa, cognitive-behavioral therapists employ many of the same techniques that they use to help treat people with anorexia nervosa. However, they tailor the techniques to the unique features of bulimia (for example, bingeing and purging behavior) and to the specific beliefs at work in bulimia nervosa.

BEHAVIORAL TECHNIQUESTherapists often instruct clients with bulimia nervosa to keep diaries of their eating behavior, changes in sensations of hunger and fullness, and the ebb and flow of other feelings (Stewart & Williamson, 2008). This helps the clients to observe their eating patterns more objectively and recognize the emotions and situations that trigger their desire to binge.

One team of researchers studied the effectiveness of an online version of the diary technique (Shapiro et al., 2010). They had 31 clients with bulimia nervosa, each an outpatient in a 12-week cognitive-behavioral therapy program, send nightly texts to their therapists, reporting on their bingeing and purging urges and episodes. The clients received feedback messages, including reinforcement and encouragement for the treatment goals they had been able to reach that day. The clinical researchers reported that by the end of therapy, the clients showed significant decreases in binges, purges, other bulimic symptoms, and feelings of depression.

New efforts at prevention A number of innovative educational programs have been developed to help promote healthy body images and prevent eating disorders. Here, a first-year Winona State University student swings a maul over her shoulder and into bathroom scales as part of Eating Disorders Awareness Week. The scale smashing is an annual event.

Cognitive-behavioral therapists may also use the behavioral technique of exposure and response prevention to help break the binge-purge cycle. As you read in Chapter 5, this approach consists of exposing people to situations that would ordinarily raise anxiety and then preventing them from performing their usual compulsive responses until they learn that the situations are actually harmless and their compulsive acts unnecessary. For bulimia nervosa, the therapists require clients to eat particular kinds and amounts of food and then prevent them from vomiting to show that eating can be a harmless and even constructive activity that needs no undoing (Wilson, 2010; Williamson et al., 2004). Typically the therapist sits with the client while the client eats the forbidden foods and stays until the urge to purge has passed. Studies find that this treatment often helps reduce eating-related anxieties, bingeing, and vomiting.

COGNITIVE TECHNIQUESBeyond such behavioral techniques, a primary focus of cognitive-behavioral therapists is to help clients with bulimia nervosa recognize and change their maladaptive attitudes toward food, eating, weight, and shape (Waller et al., 2014; Wonderlich et al., 2014). The therapists typically teach the clients to identify and challenge the negative thoughts that regularly precede their urge to binge—”I have no self-control”; “I might as well give up”; “I look fat” (Fairburn & Cooper, 2014; Fairburn, 1985). They may also guide clients to recognize, question, and eventually change their perfectionistic standards, sense of helplessness, and low self-concept (see PsychWatch below). Cognitive-behavioral approaches seem to help as many as 65 percent of patients stop bingeing and purging (Poulsen et al., 2014; Eifert et al., 2007).

Page 375

Other Forms of PsychotherapyBecause of its effectiveness in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, cognitive-behavioral therapy is often tried first, before other therapies are considered. If clients do not respond to it, other approaches with promising but less impressive track records may then be tried. A common alternative is interpersonal psychotherapy, the treatment that is used to help improve interpersonal functioning (Kass et al., 2013; Tanofsky-Kraff & Wilfley, 2010). Psychodynamic therapy has also been used in cases of bulimia nervosa, but only a few research studies have tested and supported its effectiveness (Poulsen et al., 2014; Tasca, Hilsenroth, & Thompson-Brenner, 2014). The various forms of psychotherapy—cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, and psychodynamic—are often supplemented by family therapy (Ambresin et al., 2014; Starr & Kreipe, 2014; le Grange, 2011).

PsychWatch

In a November 2010 review of the New York City Ballet production of The Nut-cracker, New York Times critic Alastair Macauley wrote that Jenifer Ringer, the 37-year-old dancer who played the part of the Sugar Plum Fairy, “looked as if she’d eaten one sugar plum too many” (Macauley, 2010). That harsh critique of the dancer’s weight and body set off a storm of protest throughout the country. Many regarded the reviewer’s comments as cruel, an example of the absurd aesthetic standards by which women are judged in our society—even a lithe and graceful ballet artist. The reviewer defended his position, arguing, “If you want to make your appearance irrelevant to criticism, do not choose ballet as a career” (Macauley, 2010). But, in the eyes of most observers, he had gone too far.

Unfair critique Ballet dancer Jenifer Ringer performs with partner Jared Angle in The Nutcracker.

About the only person who reacted calmly in the face of this uproar was the dancer herself, Jenifer Ringer. She even noted that “as a dancer, I do put myself out there to be criticized, and my body is part of my art form” (Ringer, 2010). It turns out that the 2010 flak was hardly the first time that Ringer’s weight and appearance had been described in unflattering terms. In a 2014 autobiography, she has revealed that her body had been an object of criticism throughout much of her professional life.

Ringer began with the City Ballet as a teenager in 1989, and by 1995 she was soloing. According to her memoir, she was also developing bulimia nervosa while her career was on the rise. She fell into a pattern of overeating and over-exercising to compensate. As she puts it, “I had lost any sense of a center for self-esteem and self-worth” (Ringer, 2014)

Decades before Macauley’s 2010 critique, many of Ringer’s dance mentors were urging her to lose weight. She recalls how legendary choreographer Jerome Robbins exhorted her, “Come on. You just need to get the weight off. Just do it. We need you” (Ringer, 2014). In fact, after a warning from a ballet master that she must “stop eating cheesecake,” Ringer’s contract with the ballet company was not renewed in 1997 (Ringer, 2014). She left dance at that time for a brief stint as an office worker.

After overcoming her eating disorder and regaining her self-esteem, Ringer rejoined the City Ballet in 1998. The next 16 years of dance represented a personal and professional triumph for her—a triumph that those harsh and unfair words in 2010 could not penetrate. By then, she was no longer an insecure person who judged herself and her body by the standards of others. Rather, as she states in her memoir, “I didn’t feel I was heavy, and someone else’s opinion of me had no power over me unless I allowed it” (Ringer, 2014).

Page 376

BETWEEN THE LINES

Celebrities Who Acknowledge Having Had Eating Disorders

Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi, reality star

Alanis Morissette, singer

Lady Gaga, singer/songwriter

Paula Abdul, dancer/entertainer

Daniel Johns, rock singer (Silverchair)

Princess Diana, British royalty

Zina Garrison, tennis star

Cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, and psychodynamic therapy may each be offered in either an individual or a group therapy format. Group formats, including self-help groups, give clients with bulimia nervosa an opportunity to share their concerns and experiences with one another. Group members learn that their disorder is not unique or shameful, and they receive support from one another, along with honest feedback and insights. In the group they can also work directly on underlying fears of displeasing others or being criticized. Research suggests that group formats are at least somewhat helpful for as many as 75 percent of people with bulimia nervosa (Valbak, 2001).

Antidepressant MedicationsDuring the past 15 years, antidepressant drugs—all forms of antidepressant drugs—have been used to help treat bulimia nervosa (Starr & Kreipe, 2014; Broft, Berner, & Walsh, 2010; McElroy et al, 2010). In contrast to people with anorexia nervosa, those with bulimia nervosa are often helped considerably by these drugs. According to research, the drugs help as many as 40 percent of patients, reducing their binges by an average of 67 percent and vomiting by 56 percent. Once again, drug therapy seems to work best in combination with other forms of therapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (Stewart & Williamson, 2008). Alternatively, some therapists wait to see whether cognitive-behavioral therapy or another form of psychotherapy is effective before trying antidepressants (Wilson, 2010, 2005).

What Is the Aftermath of Bulimia Nervosa?Left untreated, bulimia nervosa can last for years, sometimes improving temporarily but then returning. Treatment, however, produces immediate, significant improvement in approximately 40 percent of clients: they stop or greatly reduce their bingeing and purging, eat properly, and maintain a normal weight (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Richard, 2005). Another 40 percent show a moderate response—at least some decrease in binge eating and purging. As many as 20 percent show little immediate improvement. Follow-up studies, conducted years after treatment, suggest that as many as 85 percent of people with bulimia nervosa have recovered, either fully or partially (Isomaa & Isomaa, 2014; Brewerton & Costin, 2011; Zeeck et al., 2011). Research also indicates that treatment helps many, but not all, people with bulimia nervosa attain lasting improvements in their overall psychological and social functioning (Keel et al., 2002, 2000; Stein et al., 2002).

Why might some people who recover from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa remain vulnerable to relapse even after recovery?

Relapse can be a problem even among people who respond successfully to treatment (Stice et al., 2013; Olmsted et al., 2005). As with anorexia nervosa, relapses are usually triggered by a new life stress, such as an upcoming exam, a job change, marriage, or divorce (Liu, 2007; Abraham & Llewellyn-Jones, 1984). One study found that close to one-third of those who had recovered from bulimia nervosa relapsed within two years of treatment, usually within six months (Olmsted, Kaplan, & Rockert, 1994). Relapse is more likely among people who had longer histories of bulimia nervosa before treatment, had vomited more frequently during their disorder, continued to vomit at the end of treatment, had histories of substance abuse, made slower progress in the early stages of treatment, and continue to be lonely or to distrust others after treatment (Brewerton & Costin, 2011; Fairburn et al., 2004; Stewart, 2004).

Page 377

Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder

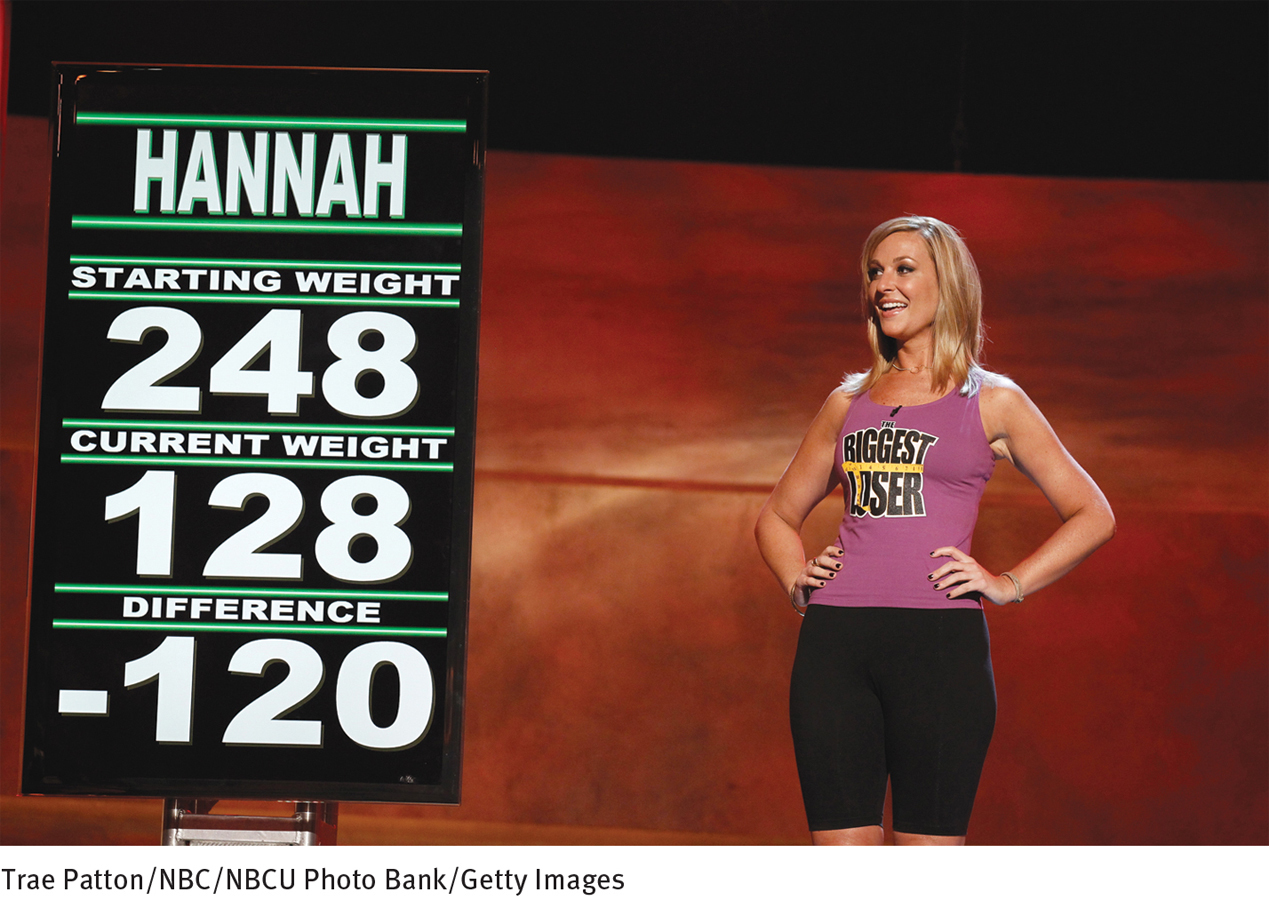

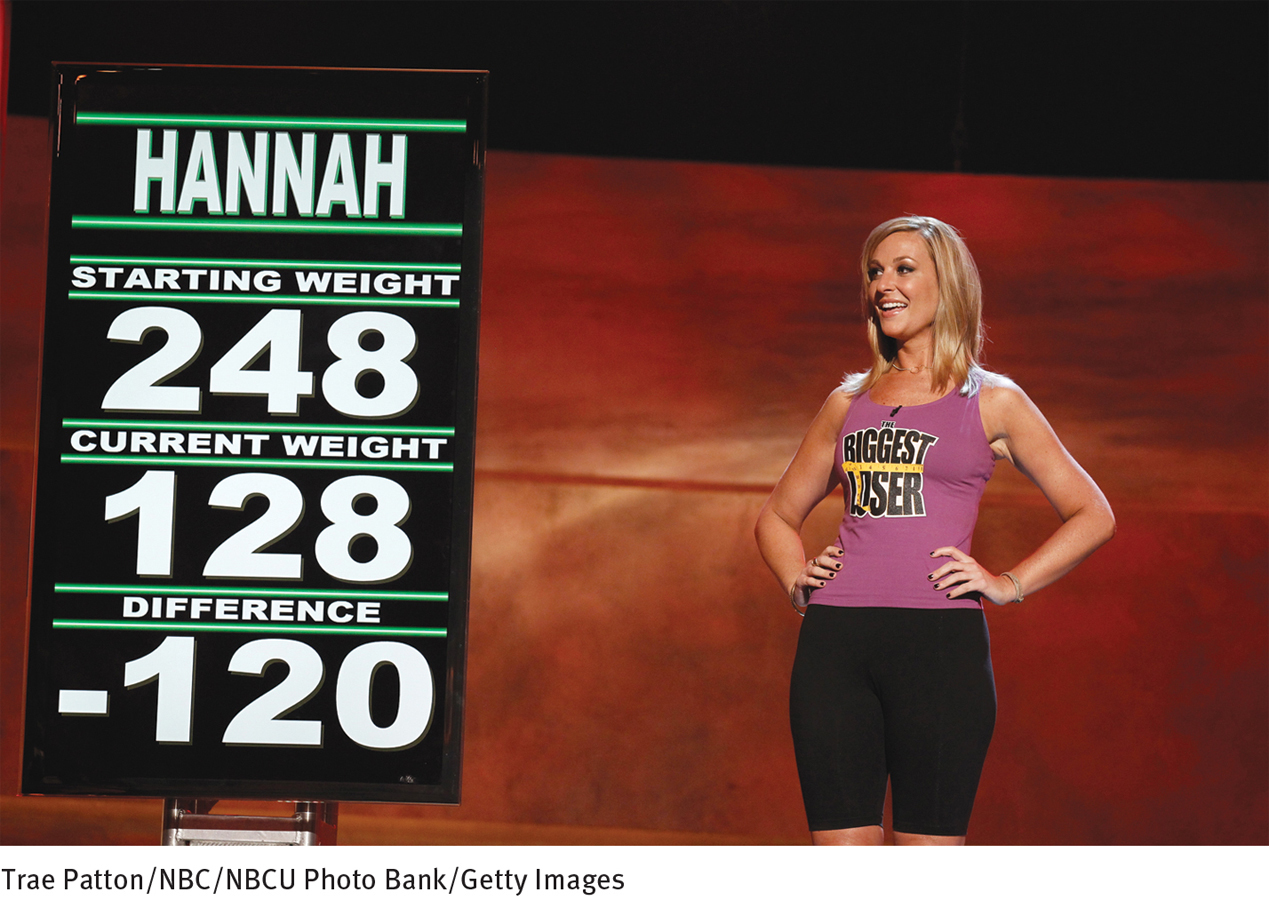

“The Biggest Loser” phenomenon Contestant Hannah Curlee proudly observes the results of her weigh-in on the 2011 season finale of the popular reality show The Biggest Loser. In this TV series, overweight contestants compete to lose the most weight for cash prizes. Most overweight people do not display binge-eating disorder, but most people with the disorder are overweight.

Given the key role of binges in both bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder (bingeing without purging), today’s treatments for binge-eating disorder are often similar to those for bulimia nervosa. In particular, cognitive-behavioral therapy, other forms of psychotherapy, and in some cases, antidepressant medications are provided to help reduce or eliminate the binge-eating patterns and to change disturbed thinking such as being overly concerned with weight and shape (Fischer et al., 2014; Reas & Grilo, 2014; Fairburn, 2013). Evidence is emerging that these kinds of interventions are indeed often helpful, at least in the short run (Fischer et al., 2014). Of course, most people with binge-eating disorder also are overweight, a problem that requires additional kinds of intervention and is often resistant to long-term improvement (Grilo et al., 2014; Claudino & Morgan, 2012; Zweig & Leahy, 2012).

Now that binge-eating disorder has been identified and is receiving considerable study, it is likely that specialized treatment programs that target the disorder’s unique issues will emerge in the coming years (Grilo, 2014). In the meantime, relatively little is known about the aftermath of this disorder (Claudino & Morgan, 2012). In one follow-up study of hospitalized patients with severe symptoms, one-third of those who had been treated still had the disorder 12 years after hospitalization, and 36 percent were still significantly overweight (Fichter et al., 2008). As with the other eating disorders, many of those who initially recover from binge-eating disorder continue to have a relatively high risk of relapse (ANAD, 2014; Stice et al., 2013).