12.5 How Are Substance Use Disorders Treated?

Many approaches have been used to treat substance use disorders (see MediaSpeak below), including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive-

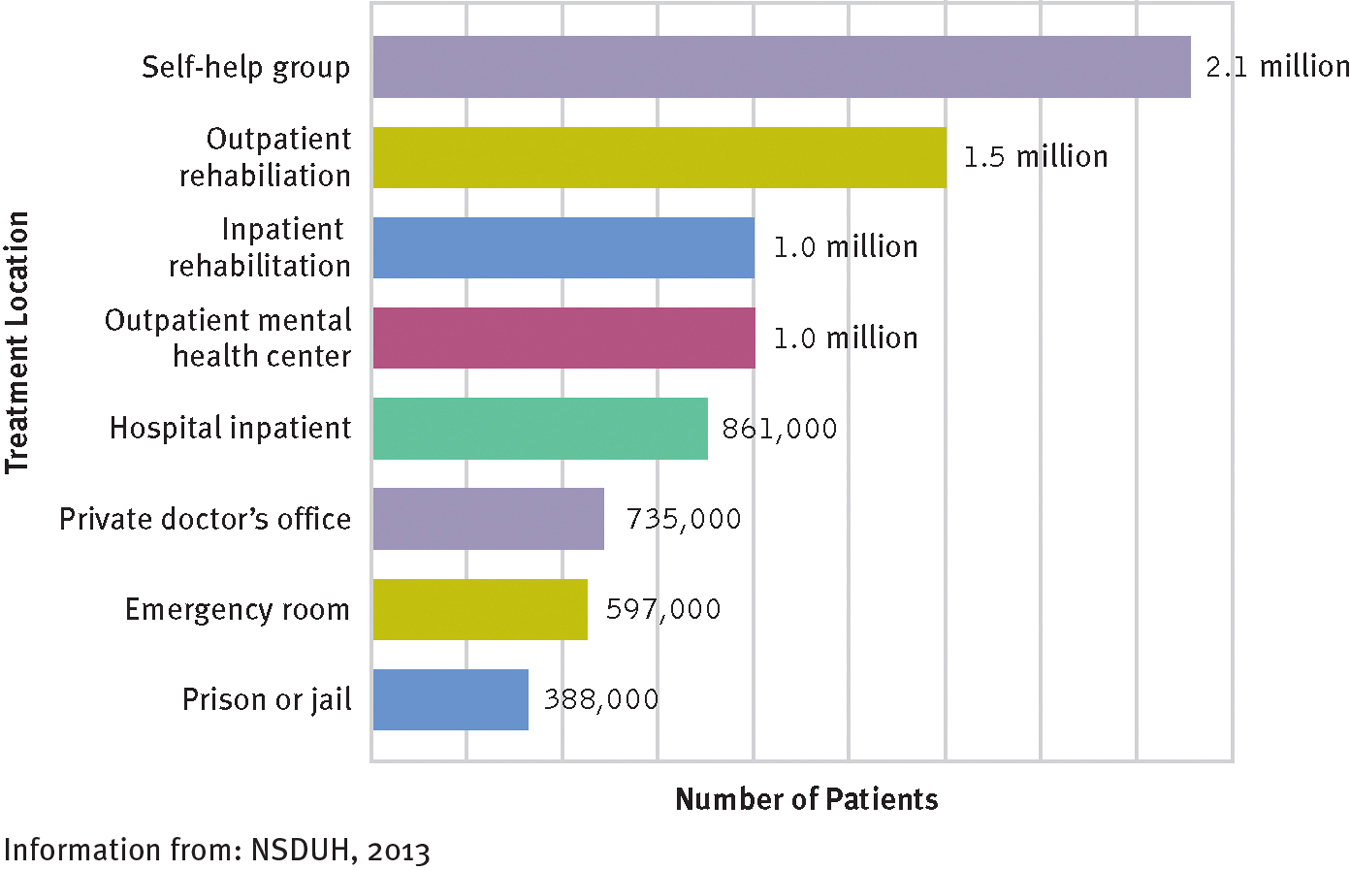

Where do people receive treatment?

Most people receive treatment for substance use disorders in a self-

The effectiveness of treatment for substance use disorders can be difficult to determine. There are several reasons for this. First, different substance use disorders pose different problems. Second, many people with such disorders drop out of treatment very early (Radcliffe & Stevens, 2010). Third, some people recover without any intervention at all (Wilson, 2010), while many others recover and then relapse (Belendiuk & Riggs, 2014). And, fourth, different criteria are used by different clinical researchers. How long, for example, must a person refrain from substance use in order to be called a treatment success? And is total abstention the only criterion, or is a reduction of drug use acceptable?

Psychodynamic Therapies

Psychodynamic therapists first guide clients to uncover and work through the underlying needs and conflicts that they believe have led to the substance use disorder. The therapists then try to help the clients change their substance-

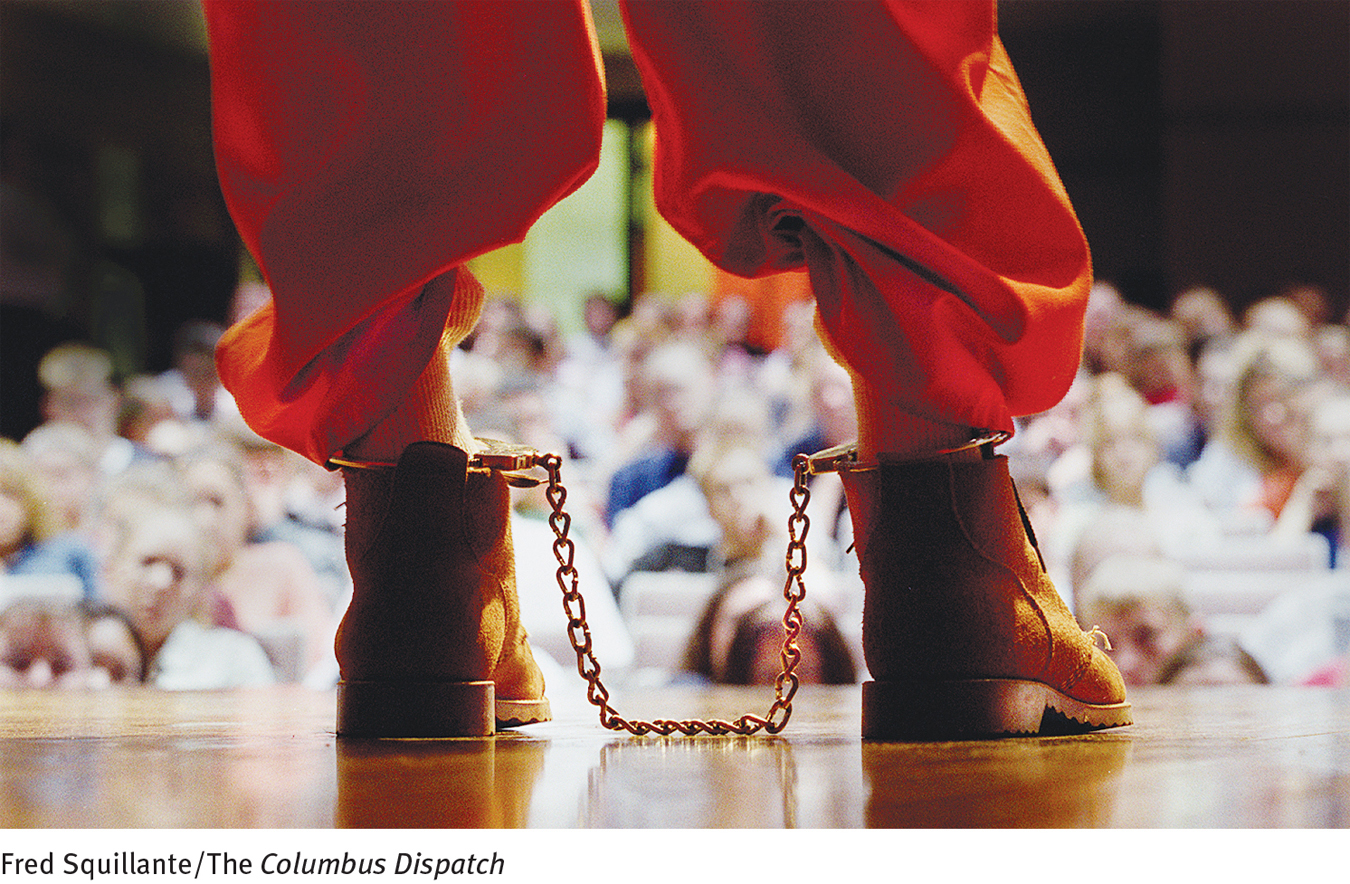

MediaSpeak

Enrolling at Sober High

by Jeff Forester

Jeff has been sober 22 months, he tells me. Without blinking or ducking, his clear blue eyes looking straight at me, he says that if it were not for Sobriety High, he’d be dead. I believe him…. Sobriety High started in Minneapolis in 1989 with just two students. It has 100 more today, and 33 sober high schools have sprung up in eight other states…. According to a National Institute on Drug Abuse study, 78% of the students in sober high schools attend after receiving formal rehab….

Enrollment is similar to any other school—

While it undoubtedly feels like a school, the wall banners feature phrases like “Turning It Over Is A Turning Point” rather than, say, a sign for the prom. The students are diverse, with hair of all different lengths and colors; some have the seemingly requisite addict tattoos while others are decked out in Goth garb and still others project a distinctly Midwestern Wonder Bread aura. Their journeys are also diverse, with the lucky ones landing here after treatment but many coming from the courts, detox or the streets….

Recovery schools fill in the educational and emotional holes opened when kids use. The classes are small so that teachers can check in with each student regularly and the curriculum flexible so as to help them with what they missed while they were using or in treatment. Some programs help students—

Effective treatments for substance use disorders are often elusive. What advantages might sober schools have over other substance abuse interventions?

All teenagers have low impulse control but the stakes are higher for chemically dependent kids trying to stay sober. Says Joe Schrank, founder of the Core Company and a board member of the National Youth Recovery Foundation (as well as a co-

Just try adding acne, constant temptation and regularly being heckled that you’re a “pussy” to a standard newcomer’s recovery and you’ll see just how high the deck is stacked against teenage sobriety; the notion of placing them in an environment that caters to clean living thus makes sense….

Ninety percent of students at Sobriety High have other mental health issues besides chemical dependency [and] need the extra support of counselors, psychologists, and ongoing mental health support, and this is costly…. “It takes more money per student, and the schools must be on a segregated site if they are to have a drug and alcohol free campus.” …

For barely sober teens … closing recovery schools would be disastrous. “Many of them will go back to the streets, or prison, or they will be dead,” says … the Sobriety High social worker….

Supporters … point out that closing recovery schools makes little fiscal sense. “Recovery school is a fraction of the cost of incarceration,” says Joe Schrank. “If you like having these kids in high school, you’ll love having them in prison.”

“Look at Drug Courts,” adds former Congressman Jim Ramstad. “The recidivism rate for those who complete the course is 24% while the rate for criminal court is 75%.” …

[Social worker Debbie Bolton] says plainly, “What we do is important. We save lives.”

“Most Sober High Schools Are Very Successful. So Why Are They Facing the Ax?” By Jeff Forester, TheFix.com (addiction website), 6/18/2011.

Behavioral Therapies

A widely used behavioral treatment for substance use disorders is aversion therapy, an approach based on the principles of classical conditioning. Clients are repeatedly presented with an unpleasant stimulus (for example, an electric shock) at the very moment that they are taking a drug. After repeated pairings, they are expected to react negatively to the substance itself and to lose their craving for it.

aversion therapy A treatment in which clients are repeatedly presented with unpleasant stimuli while they are performing undesirable behaviors such as taking a drug.

aversion therapy A treatment in which clients are repeatedly presented with unpleasant stimuli while they are performing undesirable behaviors such as taking a drug.

Aversion therapy has been used to treat alcoholism more than it has to treat other substance use disorders. In one version of this therapy, drinking is paired with drug-

I’d like you to vividly imagine that you are tasting the (beer, whiskey, etc.). See yourself tasting it, capture the exact taste, color and consistency. Use all of your senses. After you’ve tasted the drink you notice that there is something small and white floating in the glass—

(Clarke & Saunders, 1988, pp. 143–

A behavioral approach that has been effective in the short-

Behavioral interventions for substance use disorders have usually had only limited success when they are the sole form of treatment (Belendiuk & Riggs, 2014; Carroll, 2008). A major problem is that the approaches can be effective only when people are motivated to continue using them despite their unpleasantness or demands. Generally, behavioral treatments work best in combination with either biological or cognitive approaches (Belendiuk & Riggs, 2014; Carroll & Kiluk, 2012).

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies

Cognitive-

Perhaps the most prominent cognitive-

relapse-prevention training A cognitive-

relapse-prevention training A cognitive-

Several strategies typically are included in relapse-

Relapse-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Bad Age

By a strange coincidence, several of rock’s most famous stars and substance abusers have died at age 27. They include Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, Brian Jones, and Amy Winehouse. The phenomenon has been called “The 27 Club” in some circles.

Another form of cognitive-

Biological Treatments

Biological treatments may be used to help people withdraw from substances, abstain from them, or simply maintain their level of use without increasing it further. As with the other forms of treatment, biological approaches alone rarely bring long-

DetoxificationDetoxification is systematic and medically supervised withdrawal from a drug. Some detoxification programs are offered on an outpatient basis. Others are located in hospitals and clinics and may also include individual and group therapy, a “full-

detoxification Systematic and medically supervised withdrawal from a drug.

detoxification Systematic and medically supervised withdrawal from a drug.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Celebrities Who Have Died of Substance Overdose in the Twenty-

|

Philip Seymour Hoffman, actor (polydrug, 2014) |

|

Cory Monteith, actor (polydrug, 2013) |

|

Whitney Houston, singer (cocaine and heart disease, 2012) |

|

Amy Winehouse, singer (alcohol poisoning, 2011) |

|

Michael Jackson, performer and song- |

|

Heath Ledger, actor (prescription polydrug, 2008) |

|

Anna Nicole Smith, model (prescription polydrug, 2007) |

|

Ol’ Dirty Bastard, rapper, Wu- |

|

Rick James, singer (cocaine, 2004) |

|

Dee Dee Ramone, musician, The Ramones (heroin, 2002) |

After successfully stopping a drug, people must avoid falling back into a pattern of chronic use. As an aid to resisting temptation, some people with substance use disorders are given antagonist drugs, which block or change the effects of the addictive drug (Chung et al., 2012; O’Brien & Kampman, 2008). Disulfiram (Antabuse), for example, is often given to people who are trying to stay away from alcohol. By itself, a low dose of disulfiram seems to have few negative effects, but a person who drinks alcohol while taking it will have intense nausea, vomiting, blushing, a faster heart rate, dizziness, and perhaps fainting. People taking disulfiram are less likely to drink alcohol because they know the terrible reaction that awaits them should they have even one drink. Disulfiram has proved helpful, but again only with people who are motivated to take it as prescribed (Diclemente et al., 2008). In addition to disulfiram, several other antagonist drugs are now being tested.

antagonist drugs Drugs that block or change the effects of an addictive drug.

antagonist drugs Drugs that block or change the effects of an addictive drug.

Antagonist DrugsFor substance use disorders centered on opioids, several narcotic antagonists, such as naloxone, are used (Alter, 2014; Harrison & Petrakis, 2011). These antagonists attach to endorphin receptor sites throughout the brain and make it impossible for the opioids to have their usual effect. Without the rush or high, continued drug use becomes pointless. Although narcotic antagonists have been helpful—

So-

Research indicates that narcotic antagonists may also be useful in the treatment of substance use disorders involving alcohol or cocaine (Harrison & Petrakis, 2011; Bishop, 2008). In some studies, for example, the narcotic antagonist naltrexone has helped reduce cravings for alcohol (O’Malley et al., 2000, 1996, 1992). Why should narcotic antagonists, which operate at the brain’s endorphin receptors, help with alcoholism, which has been tied largely to activity at GABA sites? The answer may lie in the reward center of the brain. If various drugs eventually stimulate the same pleasure pathway, it seems reasonable that antagonists for one drug may, in a roundabout way, affect the impact of other drugs as well.

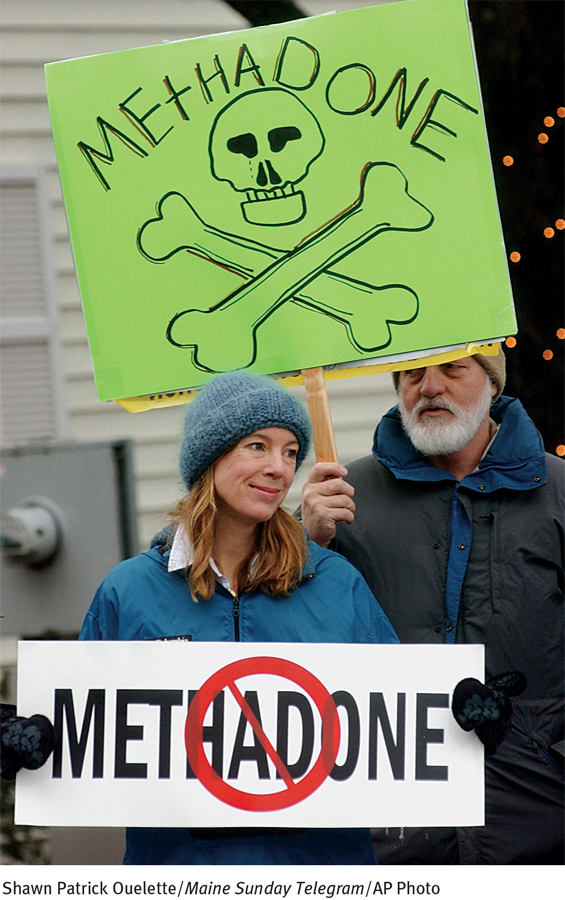

Drug Maintenance TherapyA drug-

methadone maintenance program A treatment approach in which clients are given legally and medically supervised doses of methadone—

methadone maintenance program A treatment approach in which clients are given legally and medically supervised doses of methadone—

Why has the legal, medically supervised use of heroin (in Great Britain) or heroin substitutes (in the United States) sometimes failed to combat drug problems?

At first, methadone programs seemed very effective, and many of them were set up throughout the United States, Canada, and England. These programs became less popular during the 1980s, however, because of the dangers of methadone itself. Many clinicians came to believe that substituting one addiction for another is not an acceptable “solution” for a substance use disorder, and many people with an addiction complained that methadone addiction was creating an additional drug problem that simply complicated their original one (Winstock, Lintzeris, & Lea, 2011; McCance-

Despite such concerns, maintenance treatment with methadone—

Sociocultural Therapies

As you have read, sociocultural theorists—

Self-

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) A self-

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) A self-

Today AA has more than 2 million members in 114,000 groups across the world (AA World Services, 2014). It offers peer support along with moral and spiritual guidelines to help people overcome alcoholism. Different members apparently find different aspects of AA helpful. For some it is the peer support; for others it is the spiritual dimension (Tusa & Burgholzer, 2013). Meetings take place regularly, and members are available to help each other 24 hours a day.

By offering guidelines for living, the organization helps members abstain “one day at a time,” urging them to accept as “fact” the idea that they are powerless over alcohol and that they must stop drinking entirely and permanently if they are to live normal lives (Nace, 2011, 2008). AA views alcoholism as a disease and takes the position that “Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic” (Rosenthal, 2011; Rosenthal & Levounis, 2011, 2005; Pendery et al., 1982). Related self-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Staying Sober

48% of current AA members have been sober for more than 5 years.

24% of current AA members have been sober for 1–

5 years. 37% of current AA members have been sober for less than 1 year.

(Information from: aa World Services, 2014)

It is worth noting that the abstinence goal of AA is in direct opposition to the controlled-

Research indicates, however, that both controlled drinking and abstinence may be useful treatment goals, depending on the nature of the particular drinking problem. Studies suggest that abstinence may be a more appropriate goal for people who have a long-

Many self-

residential treatment center A place where people formerly addicted to drugs live, work, and socialize in a drug-

residential treatment center A place where people formerly addicted to drugs live, work, and socialize in a drug-

The evidence that keeps self-

Culture-

Similarly, therapists have become more aware that women often require treatment methods different from those designed for men (Lund, Brendryen, & Ravndal, 2014; Greenfield et al., 2011). Women and men often have different physical and psychological reactions to drugs, for example. In addition, treatment of women with substance use disorders may be complicated by the impact of sexual abuse, the possibility that they may be or may become pregnant while taking drugs, the stresses of raising children, and the fear of criminal prosecution for abusing drugs during pregnancy (Finnegan & Kandall, 2008). Thus many women with such disorders feel more comfortable seeking help at gender-

What different kinds of issues might be confronted by drug abusers from different minority groups or genders?

Community Prevention ProgramsPerhaps the most effective approach to substance use disorders is to prevent them (Sandler et al., 2014; Whitesell et al., 2014). The first drug-

Some prevention programs are based on a total abstinence model, while others teach responsible use. Some seek to interrupt drug use; others try to delay the age at which people first experiment with drugs. Programs may also differ in whether they offer drug education, teach alternatives to drug use, try to change the psychological state of the potential user, help people change their peer relationships, or combine these techniques.

Prevention programs may focus on the individual (for example, by providing education about unpleasant drug effects), the family (by teaching parenting skills), the peer group (by teaching resistance to peer pressure), the school (by setting up firm enforcement of drug policies), or the community at large. The most effective prevention efforts focus on several of these areas to provide a consistent message about drug misuse in all areas of people’s lives (Hansen et al., 2010). Some prevention programs have even been developed for preschool children.

Two of today’s leading community-

What impact might admissions by celebrities about their past drug use have on people’s willingness to seek treatment for substance use disorder?

Community-